Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘I was confused and inspired. I wanted to do everything’

As an architect and a teacher, Toshiko Mori made her name by making statements

Part of the Experience series

Leaders at Harvard in and out of the classroom tell their stories in the Experience series.

“Architecture is a noble profession, and ultimately it exists to improve the quality of life. Each opportunity we are given to build a project, we take as a gift. In return, we engage with each project with compassion, attempting to capture an ethereal vision that will carry it into the future.” — Toshiko Mori, “Toshiko Mori Architect” (The Monacelli Press, 2008)

Toshiko Mori grew up amid the devastation and scarcity of post-World War II Japan, witness to resilience, recovery, and ingenuity on a national scale. Though her family would settle in America to begin a prosperous new life, she carried with her those indelible memories of her home country building toward renewal.

In 1981, she founded Toshiko Mori Architect, the New York City-based firm where she maintains a robust practice. She has earned many of the profession’s highest honors, including the Academy Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2005 and the 2017 Institute Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects.

Mori’s work pushes beyond the strictures of tradition, pulling from disciplines outside of architecture, including art, poetry, and fashion, while preserving the idea of buildings as positive catalysts for the lives of those who use them. The firm’s projects have ranged from private homes to museums in Brooklyn and Rockland, Maine, to an innovative arts and cultural center in rural Senegal. Her latest venture, an expansion of the Watson Institute of International & Public Affairs at Brown University, opens this fall.

Taking to heart what her mentor, John Hejduk, once called an architect’s “social contract” with the next generation, Mori has taught for more than 35 years — first at her alma mater, Cooper Union, and since 1995 at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she was the first woman to earn tenure and the first to chair the department of architecture.

Mori is the Robert P. Hubbard Professor in the Practice of Architecture at GSD.

You spent your early childhood in Kobe, Japan, before you came to the United States. Tell me about your family life in those days, the early 1950s.

This was post-World War II. Japan was still occupied by the United States. We went through a food shortage, so we had a family garden where my grandmother cultivated vegetables and I was in charge of chickens and eggs. We were very self-sufficient. War does not discriminate. We all lost our homes. My father rebuilt our house. No one made toys or clothes, so they were handmade by my mother or my grandmothers. The kids all shared toys and played together; the community had to share to recover from the damages and tragedy of the war.

A family trip to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in Mori’s formative years had a lasting impact. “I have a visceral memory of exactly what a nuclear bomb does and what human beings, what children will look like when this takes place, so this was a very significant experience for me.”

Courtesy of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

How did your father know how to design a house? Was he trained or was that just out of necessity?

By necessity. We had land and he worked with the builders. He built a very nice open-plan house, which was not traditional. It had a continuous terrace, plenty of sunlight, and a large garden which my grandmother cultivated. It was not an easy time to grow up, in terms of the scarcity of food and materials, but I never felt deprived.

What did your father and grandfathers do for work?

On my father’s side, they all had been in international business, meaning trading. My great-grandfather was an antiques and lumber dealer. They came from Nagasaki. My grandfather represented foreign finance and a pharmaceutical company. He was interested in introducing Western medicine and establishing and operating foreign banking systems. My maternal grandfather was a civil engineer and scholar whose expertise was irrigation technology. He received numerous awards and medals from the emperor. He was also a feng shui master and often took me to the field to teach me about siting.

My father worked for an international trading company which originated in Kobe. It was founded by an amazing woman entrepreneur, Yone Suzuki, who built the basis of what we know as the international trade companies of Japan today. She was his boss.

He spoke fluent Spanish, so Central and South America were his main territories. He brought back a lot of music and photographs of archaeology of Latin America, and numerous stories about the culture. When I was in elementary school, he was stationed in New York. He would come back and forth, and then eventually, when I was in junior high school, we all moved to New York.

I understand he organized a family trip to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum that had a lasting impact on you. What do you remember about that experience?

Because my father served in the army, he was exposed to the atrocities of war. And when he came back, he became an absolute pacifist: “There should not be any war.” He was very vocal about it. He said, “There’s this new museum built in Hiroshima, it really is an amazing building.” He did not have special knowledge about architecture, but he had a sense of what constitutes a great building. And this was one of the first buildings designed by Kenzō Tange, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

My father had bought a car, and he piled everybody in and we drove to Hiroshima: “We have to see this, and you have to experience it so that you’ll never think of supporting war ever in your entire lifetime.” My parents would tell us their stories during the war period, but he would get very upset talking about it — those memories were very painful to our parents — so he wanted us to see the aftereffects of it on our own.

The building is a very simple one. It’s called piloti, on stilts. It’s raised above the ground and through the pillars you can see the destroyed Hiroshima dome, which remains as an eternal memory of destruction.

It’s a modernist building influenced by Western architecture. You go up a floor of a building and inside there is a museum. The materials and the photographs from that period are very raw. The curators just showed it as is. You can imagine, for a child, it was a shocking and traumatizing experience. It took a long, long time for anyone to recover from Hiroshima, but that’s the impact I’m sure the curators and designer of the museum wanted. You share the impact visually, you share the experience of going through it, what it is like to expose any populace to that kind of horror. What it does to people, what it does to the places. When you’re talking about nuclear holocaust, it’s very abstract. But I have a visceral memory of exactly what a nuclear bomb does and what human beings, what children will look like when this takes place, so this was a very significant experience for me.

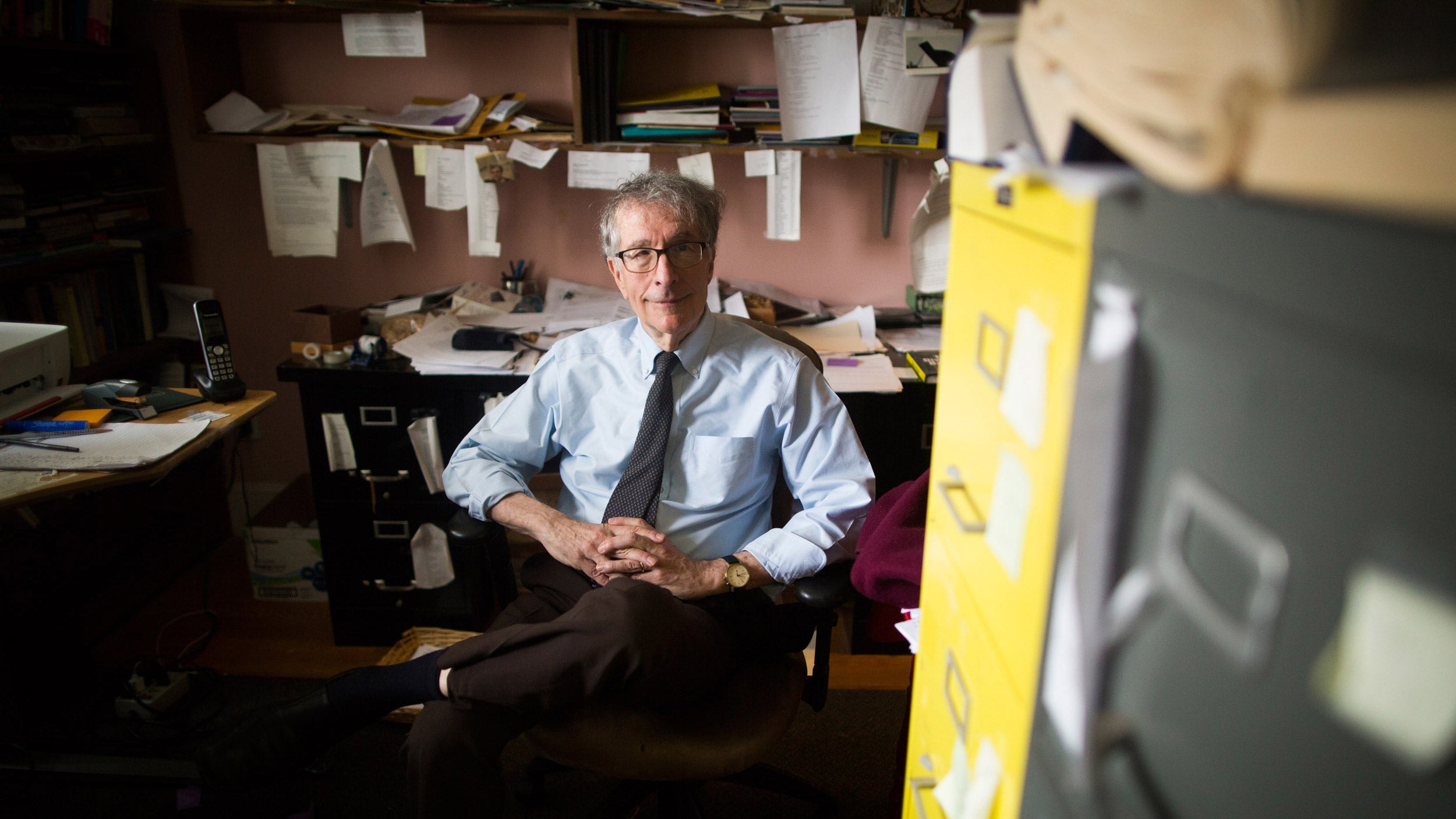

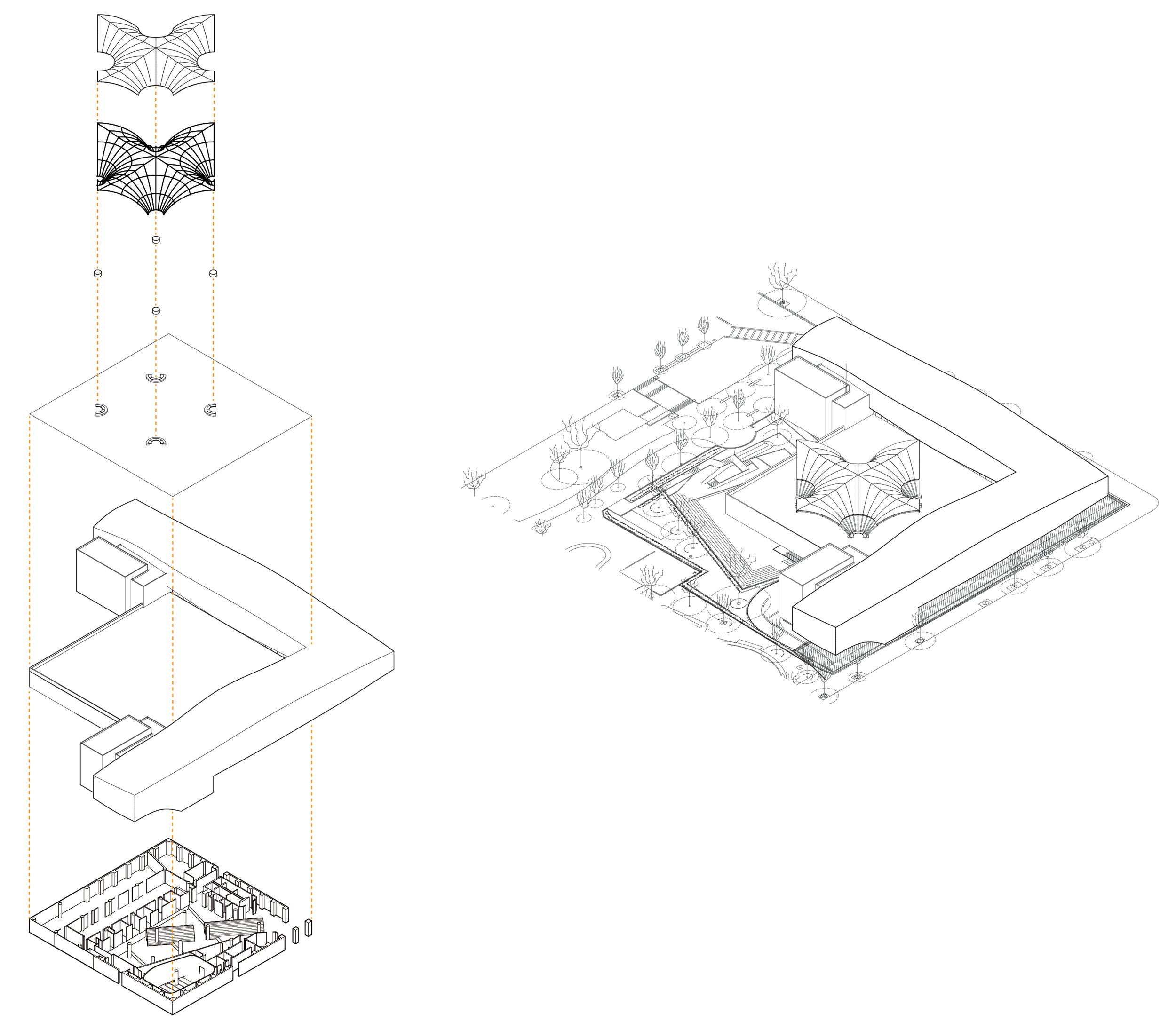

Thread Artists’ Residences & Cultural Center (Sinthian, Senegal)

Photo by Iwan Baan

Mori discusses the Thread project, above

transcript

Transcript:

Mori: Situated in the remote community of Sinthian, Senegal, in South Saharan Africa near the fragile border of Mali, this project offers multiple programs for the community, including gathering space, performance center, and residency for visiting artists. A collaboration with the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and American Friends of Le Korsa, the cultural facility is intended to complement the existing clinics, kindergarten, and farming school on site. It is also meant to ensure stability and provide a common ground within a community consisting of twelve different tribes. The shared music, art, and performance programs are a testament to the resiliency of the region.

In the design, a parametric transformation of the traditional pitched roof is achieved through a process of inversion, inscribing a series of courtyards within the plan of the building and simultaneously creating shaded studio areas around the perimeter of the courtyard. The inversion of the roof also creates an effective strategy for the collection and storage of rainwater in cisterns. With a total footprint of 11,285 square feet, the project is capable of fulfilling substantial domestic and agricultural water needs for the community.

Relying exclusively on local materials and construction techniques, the building’s traditional structure is formed primarily of large bamboo members and compressed earth blocks. Climatic considerations figure prominently into the building’s form and specify the orientation of the studios and covered gallery areas. The building also offers ample shading of outdoor areas and considers wind orientation for ventilation. Climatic comfort is reinforced through multiple overhangs and spaced-brick walls that absorb heat and allow for airflow through the building interior. In addition to local material, project management will be undertaken by local villagers. The project offers an iconic shape in a landscape that is a vast, flat bush land.

The family moved to New York when you were 14. What was that like? Leaving all your friends behind must have been hard, especially at that age.

It was a very, very big change. English was not my strongest subject matter at all. I liked literature. I was reading everything, and my favorite activity was reading Japanese literature, from very ancient authors to the contemporary, anything that I could get my hands on. I always wanted to be a Japanese writer, so I really didn’t need to go to America [laughter].

When did you first discover your interest in art?

I liked to draw all the time. Either I read or I drew — that’s all I did as a child. And I liked to make things by hand. I think that reflects on the fact that I saw my mother and my grandmother making everything by hand, from toys to dolls to cooking to repairing our furniture; we could not buy things in stores. The idea of making things to be self-sufficient was interesting to me. It led to sculpture and the arts.

And then I became interested in American and Western literature, especially French literature. I liked taking French classes very much. Also, I liked to read scientific journals. I was interested in a lot of things and, as a result, I couldn’t make up my mind as to what I wanted to do.

“It’s a bit of a cliché that Renaissance architecture made me realize what I wanted to do, but it’s really true.”

When did you decide?

In my high school, they didn’t have a strong art curriculum and I wanted to study art. When I talked to my father, he said, “Maybe you can take a summer course.” I found a summer course which brought you to Paris and Florence. It was organized by a college consortium. I got instruction in art history, architectural history, and drawing and painting. In Paris, it was right at the Sorbonne. I was a junior in high school, and that was like a dream come true.

Were you by yourself or with a group of students?

I went alone and I met other kids there, in Paris and then going to Florence to see Renaissance art. The instructor in Florence was a graduate of Cooper Union [in New York] and he studied architecture. In Florence, you really don’t separate architecture from painting and sculpture. In the work of artists or architects, they were doing everything at the same time. And then, of course, in the Renaissance, there were scientific discoveries. You really saw how artists integrated the arts and sciences into artistic production. I was confused and inspired. I wanted to do everything. It’s a bit of a cliché that Renaissance architecture made me realize what I wanted to do, but it’s really true.

You didn’t want to have to choose one or the other?

No, you can do art and architecture. But I didn’t know what architecture was at all, I just liked it, so I was visiting different buildings and reading about them. Leonard Meiselman, the instructor from Cooper Union, introduced me to a dean of the School of Art at Cooper Union as a potential candidate. I got accepted. I got into other schools, too, but I really wanted to go to Cooper Union.

My father was skeptical about sending me to art school, but then, he’s a businessman, so I appealed to his business instinct. Because Cooper Union is free tuition, I said to my dad, “Look, that’s like the best deal you can take. You don’t have to pay anything for me to go to college. Why wouldn’t you take it?” He said, “OK, done deal.”

Photo by Hiroshi Abe

Mori discusses the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, above

transcript

Transcript:

Mori: The Brooklyn Children’s Museum rooftop canopy is a three-season open-air pavilion on top of the existing museum’s roof terrace. The canopy is a covered courtyard for multi-purpose exterior activities for kids. Thirteen 6-inch diameter steel tubes spring out from 11-foot semi circular bases at four occasions to form a hybrid vaulted roof structure. It’s light weight is required because a museum has to be in operation all the time and construction was completely accessed from outside while activities was going on. The 7,300-square-foot clear span gives a simplicity of arches and steel structure, single radius curves, and the structurally efficient arch span allows the roof to remain slender and light. The use of ETFE (Ethylene Tetra Fluoro Ethylene) cladding is a material originally developed for the space industry which creates a highly durable translucent self cleansing roof pillow. Up lights at the column bundle bases create a luminous effect at night. It will function as a classroom and play area and open-air performance space. A gathering space with flexible seating arrangement for fundraising events and social events has been booked all the time in the warmer months for casual outdoor dining and for the existing cafe.

For the rooftop canopy, which had to be lightweight because the museum remained open during construction, Mori turned to a durable, translucent material developed for the space industry.

Courtesy of Toshiko Mori Architect

When did architecture start tugging at you?

I took to sculpture, which is already art meets architecture. We had an amazing shop with equipment and tools. I was hanging out in the shop quite a bit, and saw architecture students coming in, making models. I became friends with them and visited them in the studios and got really interested in it.

One of our assignments was to transform a space. The transformation of space was an abstract idea. Three of us in class decided to paint one of the corridors from end to end all white. We picked a corridor in the architecture school. We started from one end, on a ladder, and we started painting. And the dean of the school of architecture, John Hejduk [M. Arch. ’53], walked by and asked us, “What are you doing?” We said, “This is our art project and assignment. It’s about transformation of space, so we are painting this corridor white.” And he kind of looks at us and says, “Did anyone give you permission?” We said no [laughter]. He looked at us like, So you think this is going to transform space? And then he said, “I like it.” He let us finish it and we presented it. We didn’t realize that Hejduk was one of the New York architects in what was called the White School and Gray School. He was one of the “whites,” so we hit the right color with the right person. That was the beginning.

Why architecture? Were you losing interest in art at that time or did you simply feel that architecture offered more challenges?

Art can be very isolating: you’re creating things on your own. It could be also quite socially isolating and not engaged with the larger environment. I think these days artists are working much more in crossover territories. Also, I wanted to learn more about specifics of how to make buildings — structures, the history behind them, sciences, physics. I was voracious in terms of wanting to learn more complex things. I thought in the end that the architecture curriculum was much better suited for me.

“I think one needs to speak up and one needs to be decisive and aggressive.”

Who were some of your mentors? Were there specific architects or styles that you were drawn to? I assume Dean Hejduk was important to you.

Yes, exactly right. He’s one of them. He had been a mentor as a student, because that’s how we met. And then afterward, he invited me to teach at Cooper Union, and he was a mentor in terms of teaching me by example how to teach. You really have to learn by osmosis.

I always admired Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In specifics, I would say Mies van der Rohe and also Alvar Aalto. Those two architects are the ones whose work I admired very much. Mies van der Rohe’s work is about abstraction and simplicity, but it does not lose complexity. And he reduces architecture to the essential without losing an impact. In a sense, his work is about reduction without deletion. It’s inclusive and it’s incredibly rich and dense material, but without cutting off complexity. I also like how he was disciplined and rigorous in terms of expression of architecture.

Alvar Aalto was a Finnish architect who was a modernist. Early on, his work was in relationship to nature, environment, daylight, so the forces of nature had enormous impact on his architecture.

How did you end up working as a drafter for the renowned artist, sculptor, and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi?

When I was a student, one of my professors recommended me to work for Noguchi, to help him on my school holidays and weekends. I would go to his studio and I would draw, because he wouldn’t really draft. His office — he shared it with Buckminster Fuller — was called Noguchi Fountain & Plaza, Incorporated. The two of them would go after public projects together. Those two were best friends, but they were polar opposites, because Fuller believed in everything artificially constructed — manmade technology, ideas of geometry — whereas Noguchi was completely into natural materials, natural elements: humans, stones, water. Because of that, I was drawing parks, public plazas, larger site plans, which neither of them would really focus on as much.

Was that intimidating? You were young and new to the field and you’re working for these two—

Two giants? Yes. They were very nice. They were very funny, it was a very family-like atmosphere, and every day we’d have lunch. In Long Island City, where there was a studio, there was no place to go out and eat, so every lunch, everybody would sit together and have lunch and one person would cook for the whole office. And then they would have clients and other guests so it was like a family gathering all the time. I never felt them to be intimidating because when you’re young, you’re fearless.

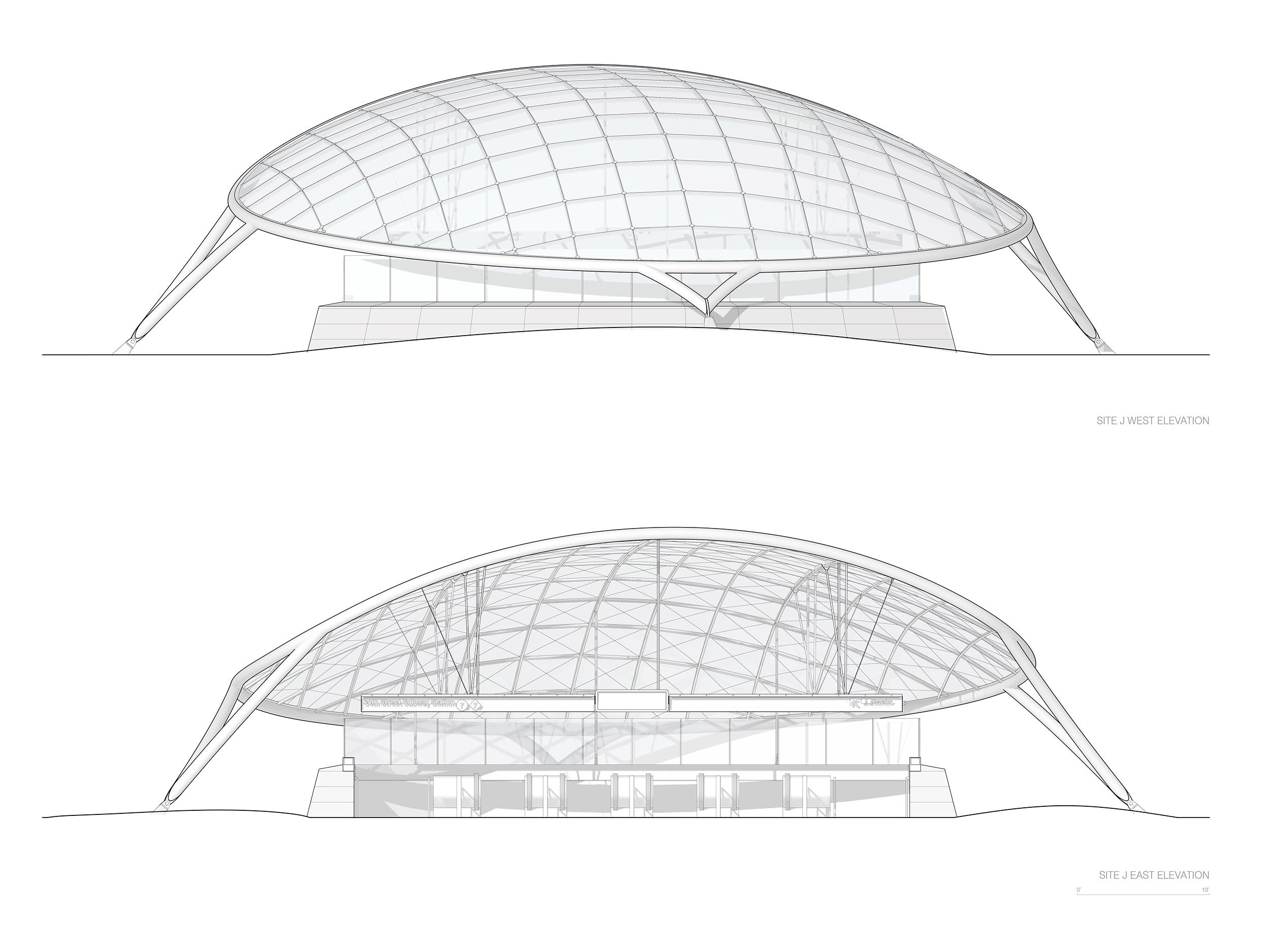

Photo by Hiroshi Abe

Mori discusses the Hudson Park subway canopy, above.

transcript

Transcript:

Mori: The Hudson Park and Boulevard project includes the design for a new four acre urban park as part of the revitalization efforts of the far west side of Midtown Manhattan. Providing much needed green space in the new mixed use neighborhood, the Hudson Park and Boulevard is an integral component to the new development that works to create a harmonic relationship between urban infrastructure and natural landscape. Two entry canopies for the 7line subway extension, a café pavilion, a playground, and a cluster of fountains are seamlessly integrated with the landscape and streetscape to create public spaces with instances of repose from the hectic pace of New York City.

The subway canopies present a unique challenge to transform a utilitarian cover into a structure in and of the landscape. Each canopy employs a lightweight grid shell spanning across the full subway entrance. It is a highly calibrated engineering piece where its geometry and shape become the structural support system. Through efficient use of material, the shell creates a light weight transparent canopy, permitting uninterrupted visual connections across the park.

Mori sought to create a “harmonious relationship between urban infrastructure and natural landscapes” when designing the Hudson Park subway canopies.

Courtesy of Toshiko Mori Architect

You followed a traditional career path for those first few years after Cooper Union. You worked for a very established firm, Edward Larabee Barnes. But did you always know that one day you would set up your own shop?

I had a plan. I kind of knew I wanted to do work on my own in any case. And then I went to work at Ed Barnes’s office. It was a very nice office. You could do anything. He was very good friends with Noguchi, too, so it was a similar atmosphere. If you wanted to do work, you could do more work, take on more responsibilities. It wasn’t so hierarchical. But I knew that, in offices like that, you decide what you want to do and what you want to learn, and then at one point, you are not learning as much if you stay there. You have to do something else. You have to keep constantly challenging yourself to do something. I think I always had a desire to test my ability.

Starting a business is challenging at any age, but you were a woman in your 20s when you launched your firm, Toshiko Mori Architect. Was there someone encouraging you to take that chance?

I think John Hejduk always set us up knowing that our biggest asset of youth was to be fearless. Basically he told us to go out and take over the world. He told us, “Oh, your thesis is great! You should all try to get your thesis built!” So, of course, we believed it. ‘Our dean says our thesis is great, it should be built, so we have to figure out how to get it built!’

My thesis was called “Places of Transaction.” It’s about the typology of markets, from farmers markets to ancient markets in Rome to stock markets. Different places where goods and monies can exchange, so it’s just really the intersection of many different economies and cultures, many people, the social space. This interaction was very interesting to me and I had one prototype of a market, which I built.

In New York, there’s a shop which still exists, called Henri Bendel, that used to be on 57th Street, run by a woman named Geraldine Stutz. It was [a vertical] street of shops and different boutiques of different designers. So I made an appointment with Geraldine Stutz. I showed her my thesis. She looks at it and says, “Why are you showing me your thesis?” “Well, you’re interested in places of transaction and this is a prototype. I think you should build this.” [Laughter.] She says there happens to be a Japanese fashion designer who she is going to introduce to the U.S. and perhaps this prototype should be her new shop.

“You have to keep constantly challenging yourself to do something. I think I always had a desire to test my ability.”

Who was the designer?

Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons. This was her first shop.

You didn’t realize what a leap of faith you were taking at the time.

Well, I think that’s the best thing. I tell my students to do that. I think if you start thinking about it too hard, you won’t be able to do anything.

So that was your first big break.

That Comme des Garçons shop, 165 square feet. A family called the Weisers had series of shops called Charivari. The Weisers had seen it and they loved it, so they asked me to design new shops for them, so I did a number of Charivari shops. They were like Barney’s; they collected fashion designers from all over the world. From there, I ended up doing showrooms and then boutiques. I ended up doing more work for Comme des Garçons, and then, eventually, Issey Miyake. Fashion designers are wonderful because they are creative and they understand.

Because you don’t have to explain certain things, they just get it?

Right. One of the things about those boutique designs was that I was experimenting with different materials, so I think that provided a really interesting platform for experimentation, innovation, which turns back into my long-term interest in material exploration, fabrication, and techniques.

Your interest in textiles and weaving in architecture that we see so clearly in the Thread project, in Senegal, comes from that early exposure to fashion?

Issey Miyake would be working with textile designers, so you’d see how it’s being woven. Some of them are hand-woven, mechanically woven, some are digitally woven. I’ve learned so much about possibility of different types of material, mixing materials and layering together, or pleating together, and expanding together, and interaction between what I call in my research the three modes of fabrication: hand-made, machine-made, and digital fabrication. That really comes from my observations of their work and techniques.

“The interweaving of exterior spaces and interior spaces creates a new relationship between a city and a gallery.”

Courtesy of CMCA

Mori discusses the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, above

transcript

Transcript:

Mori: The Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) is engaged in the expansion of its mission in advancing contemporary art in Maine. The new museum will be a mixed-use complex of galleries, public space, and educational spaces, reflecting CMCA’s goals to provide a platform for larger contemporary art dialog. CMCA’s new home will be in the City of Rockland, thereby completing a cultural triangle that consists of the Farnsworth Art Museum and the Strand Theater, thus anchoring Rockland as a major cultural arts destination along the Maine seacoast.

The overall form and materials of the building hearken back to Rockland’s industrial seacoast past, interweaved with refined detailing and precise control of proportions to elevate the project to CMCA’s lofty ambitions.

The entry to the building is an exterior courtyard, the proportions of which echo the large interior two-story gallery space, naturally day lit through the use of saw tooth skylights. The connection of the two large spaces – one exterior, the other interior – blends the concept of art viewing with that of the public sphere. The interweaving of exterior spaces and interior spaces creates a new relationship between the city and the gallery.

The educational component of CMCA’s program furthers the symbiotic relationship between the gallery and the public sphere. Within the complex is a sixty person lecture hall that will engage the community in arts education through a series of lectures, gallery talks, video screenings, and workshops. In addition, a classroom specifically dedicated to CMCA’s younger patronage will provide the tools needed for hands-on arts education. These programs further CMCA’s goals to engage the gallery to its community and to the larger discourse beyond.

You taught at Cooper Union for many years in the 1980s and 1990s before you came to Harvard in 1995. You were the first woman to receive tenure at the Graduate School of Design. Were you aware of that distinction at the time, and why do you think it took so long?

I had no idea. I don’t think I knew it [laughter]. Someone said that, but it didn’t dawn on me as something significant. And later on, when it dawned on me, I went, Oh my God, ’95? That’s crazy!

Did you find it challenging to be the first?

Christine Smith joined me right afterward. There were two of us in the senior faculty. It never felt hard because my colleagues are quite fair and open and everything else. I was conscious that there were fewer women faculty, and I knew that we had to do something. I was very active in the promotion and hiring of more women faculty and tenure at the School — efforts that still need to continue.

Do women face different challenges in the field than men?

The gender imbalance in the field of architecture is exaggerated by a lack of mentors and role models. I had no female mentors or role models. We also suffer from a lack of gender balance in fields closely associated with our work, such as engineering, construction, building management, and real estate, areas where we collaborate. I see an increase of representation in some sectors, like the construction businesses, but we are no way near medicine or law in terms of highly visible representation. Architecture is filled with stereotypes and status quos that are not productive, and in a world where we increasingly require a collaborative model of production and building, I often disrupt and reset the framework and mindset to have everyone focus on common goals and vision. I think one needs to speak up and one needs to be decisive and aggressive.

How has the profession changed since you first started?

Many things are more accessible. One of the assets of digital tools is that there are much faster communications, so the process is less linear and more simultaneous — you can have everything going on at once. It creates a type of friction. It used to be much more linear. We’d do drawings, it goes to bid, and shop drawings are prepared.

In a new process today, sometimes everything gets messy and done all at once, which means there’s more access to information, but it is more challenging to negotiate without making a compromise. And then the difficulty is that you have to make decisions fairly fast, which means you have to be more informed. There was a time in which you could sit around and think about it, but this simultaneous confluence of habit of work requires more knowledge and a more informed understanding of the entire process of building, from programming to understanding to material sciences to structures and infrastructures and feedback and so forth, which is a challenge in terms of pedagogy. How do you educate students?

In this highly accelerated process, is something creative and important lost because there’s no time to reflect?

Yes. That’s actually quite dangerous. Because we’ve lost some time to reflect during a project, we have to premeditate much more. We have to think of possibilities. We have to anticipate. We do an enormous amount of scenario-building beforehand, so I think the front-end effort for architecture is much larger now. It’s more intense. Because we have to build in multiple options to assure its integrity, the creative model requires robustness for survival.

“The gender imbalance in the field of architecture is exaggerated by a lack of mentors and role models. I had no female mentors or role models.”

How should students, tomorrow’s architects, prepare?

I think they really have to promote their priorities on what they want to do, and stay proactive. Set your priority and agendas. Don’t let the outside world tell you how you should work or what you want to do. They’re GSD students. They’re all smart. They are independent. They have their own mind. Set up your goals, set up what you want to do, how you want to live, how you want to work, and then everything should follow that.

Your firm’s work doesn’t have a signature style like many other well-known architects. Is that intentional? And does traditional Japanese architecture have an influence in your work?

I always say that in architecture in my era, styles just do not exist for any of us anymore. To try to make something look like something else artificially is a totally idiotic approach, because the world is very complex and, as an architect, one has to embrace the context. We have to, within our own thinking process, digest the complexities and come up with a solution which may be a result of many, many different iterations. So imposing a style just won’t work anymore.

As architects of our time, a careful and systematic approach is what’s consistent for us. It may not look the same, but the way we deal with the context, siting ideas, idea of environment, the structure — the underlying principles in our approach — are what’s so much more significant in contemporary practice than the urge to make signature buildings.

There are certain aesthetics that people recognize as minimalist —simplicity, clarity — in our work. I never even considered imposing traditional Japanese aesthetic on a project of mine. But at the same time, when you analyze traditional Japanese architecture, one can uncover some spatial properties that relate to our work. For example, horizontality. That’s very, very strong for me — how elements connect spatially, and how the spatial framing devices are made. That’s definitely more Japanese-oriented than Western-oriented.

A private home designed by Mori in Ghent, N.Y.

Photo by Paul Warchol

What attracts you to a project? Is it the scope of challenges presented? Is it a particular location? Is it a specific client?

I think all of the above, but mostly I think my career right now, after all this, I really think that I want to work on projects that have some benefit to humanity, that create values, that do more than just accommodate and function. So we think very carefully. We talk to many people about the goal of a project. What will be the impact? What will be the implication?

What dissuades you from a project?

Usually when the purpose is completely financial, or all quantity based, which doesn’t attract me. And it goes back to my thesis of “places of transaction.” Yes, you do transact using money and goods, but the true transaction creates different values and creates the social interactions, creates cohesion. And then “economy” in that case is not just exchanging money, it’s creating a quality of spaces. I learned early on to be suspicious if it’s only about quantifying factors.

How do you determine whether a project’s successful?

If people occupy and use it. They would occupy it in a creative way, perhaps even exceeding your expectations, so that it contributes to their active participation in a community, and they’re actively using it. They might misuse it, which is just fine. I think that’s the only measure: how it’s being used, occupied, and lived in as a part of the social mechanism of the community.

What’s the role of an architect today?

Architecture is the so-called mother of all arts, so the profession is always put in a leadership position in society, but somehow we, as architects, are not part of the big decision-making processes. There’s some kind of gap in which our credibility, our credentials, our capacity, are not fully utilized within the decision-making body. I think our goal is always to improve the quality of environment and the quality of human life, so we have the right goal in mind. We have to gain a position in society where we can influence fundamental decisions that form important factors for making cities and buildings.

You’ve written about the “ethical dimension of architecture” for a number of years. How do you define that obligation for architects today?

One is, it has to be safe. Because we basically build a shelter for different populations, different uses, so safety is an obligation, safety and comfort. And then, the idea of spaces that will promote social interaction among very different types of community. Inclusion, accessibility — physical and visual accessibility — and the idea that the building also can sustain itself. It can be very costly if you’re not careful in terms of designing it to maintain it, and can waste many of our resources. How do you make a building that is very smart in terms of using its own resources to be able to maintain itself?

So you don’t necessarily mean supply-chain issues or labor concerns and those kinds of things.

Oh, that too. That’s why I’m interested in the local labor economy. When you think of a building being well maintained, you have to think of life cycle and performance, by whom and how it is maintained. Materials — where it came from, where it’s going. And then I think I’m very careful about who’s building and supply chain, because it becomes part of community. More and more people are aware of where things come from and who’s building it and how it’s used.

Was there ever a moment of doubt for you about your career, whether you’d succeed?

I’m very flexible. I have multiple goals. If one doesn’t work, I look toward another target. As architects we have to work with the force of economy. So, flexibility is absolutely the key. I think one has to set multiple goals and to be able to shift gears and just not sit in one place and think, Oh, this is not going well, so scrap it. Instead of doing that, you just move laterally to another goal and keep on going that way. I think that’s a basic survival skill for our profession.

In a speech you gave to graduating students in 2016, you spoke about the importance of resilience. Resilience in terms of structural resilience but also psychologically — being able to weather the myriad challenges that come up in a project, in a career. What did you mean by that?

I think we have to be physically resilient. And then resilient meaning not everybody will like what you do. There are always criticisms, there’s always some resistance against what you’re trying to do. So I always say, have a Teflon effect. Let things slide down, and just be resilient, meaning you just take some criticisms or take some bad feedback, but bounce back, keep on working on it. I always use two words: resilience and perseverance.

It takes a long time to get things built and to do that, you have to persevere through some circumstances which are not necessarily comfortable. Financial constraints, change of sites, many changes — it’s a lot of things, really, so you have to keep at it. Be persistent and then be resilient; always bounce back.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.