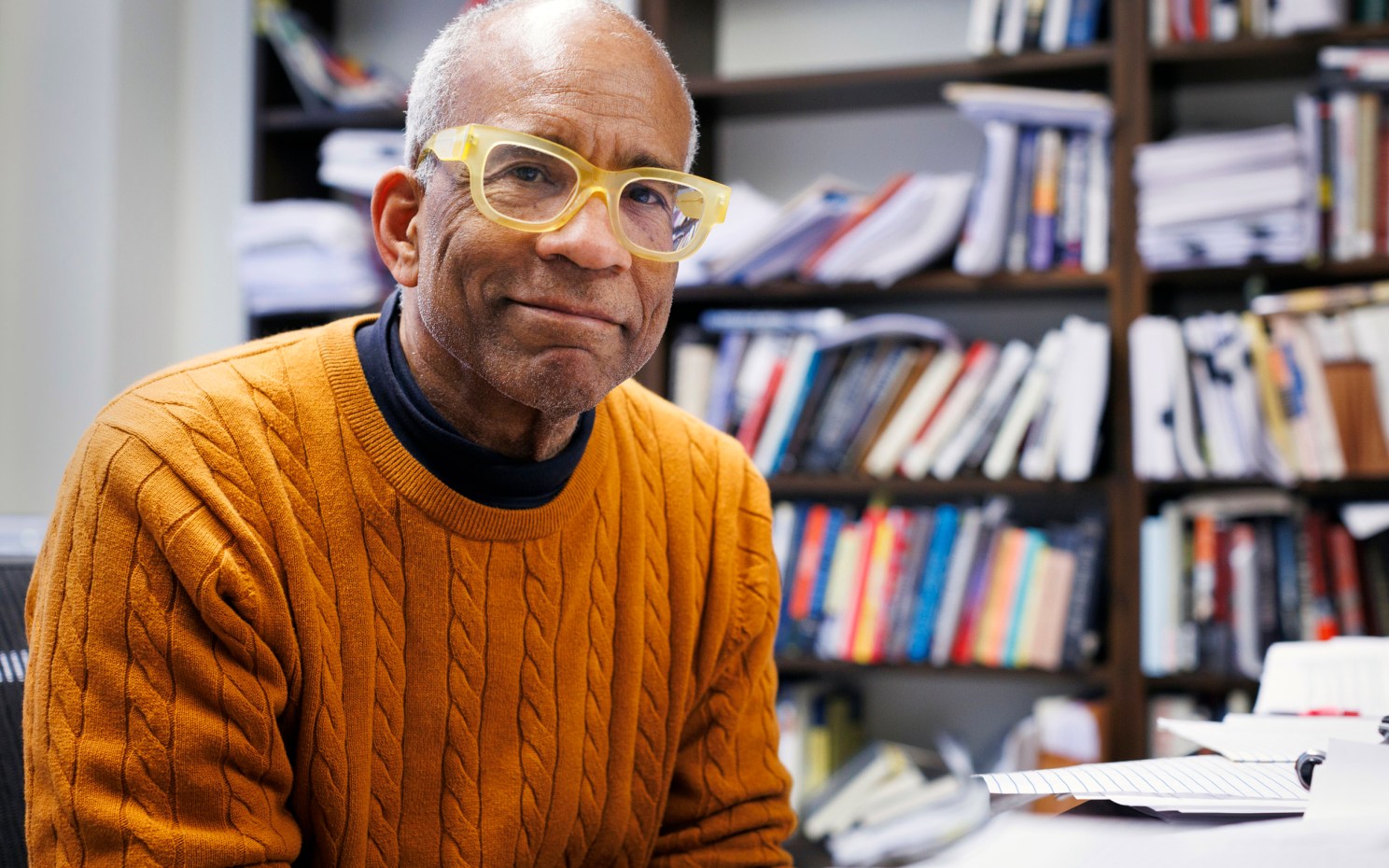

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘I’ve never done work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.’

Amartya Sen’s nine-decade journey from colonial India to Nobel Prize and beyond

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

Coming from a long line of Hindu intellectuals and teachers, Amartya Sen enjoyed advantages and freedoms that few others did in a deeply-stratified India of the 1930s, during the waning days of the British empire.

Teaching was in his blood, and from an early age, Sen was struck by the stark economic inequities he saw all around him under the British raj. Identifying and understanding the causes and effects that inequalities, like those surrounding poverty or gender, had on people’s lives would become a lifelong intellectual lodestar for the political economist, moral philosopher, and social theorist.

Many economists focus on explaining and predicting what is happening in the world. But Sen, considered the key figure at the convergence of economics and philosophy, turned his attention instead to what the reality should be and why we fall short.

“I think he’s the greatest living figure in normative economics, which asks not ‘What do we see?’ but ‘What should we aspire to?’ and ‘How do we even work out what we should aspire to?’” said Eric S. Maskin ’72, Ph.D. ’76, Adams University Professor and professor of economics and mathematics.

Over his 65-year career, Sen’s research and ideas have touched many areas of the field. He’s credited as one of the founding fathers of modern social-choice theory with his landmark 1970 book, “Collective Choice and Social Welfare.” The book took up the late Harvard economist Kenneth Arrow’s ideas from the early 1950s about how to combine different individuals’ well-being into a measure of social well-being, intensifying interest in and expanding upon Arrow’s work.

“It was really Amartya who made the field what it became,” said Maskin, a 2007 Nobel laureate in economics who has taught with Sen, the Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and professor of economics and philosophy, since the 1990s.

Sen’s 1970 paper, “The Impossibility of a Paretian Liberal,” was deeply influential on philosophy and economics. In it, he pointed to an inherent conflict between individual liberty and the principle that making people better off is always desirable.

His work on famines and his novel view that in order to accurately evaluate people’s well-being, economists needed to consider information beyond just income has reshaped thinking in development economics and welfare economics. Known as the “capabilities approach,” the study of how policy affects a person’s life opportunities, an area of economics that’s grown in recent years, “is very much based on ideas that Amartya developed years and years ago,” said Maskin.

In 1998, Sen received the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his theoretical, field, and ethics work in welfare economics and for his research advancing the understanding of social-choice theory, poverty, and the measurement of welfare.

He has received top civilian honors around the world, including France’s Légion d’Honneur (2012) and India’s Bharat Ratna (1999), as well as more than 100 honorary degrees from institutions on five continents. Sen received an honorary Doctor of Laws from Harvard Law School in 2000 and is a senior fellow in the Society of Fellows at Harvard.

At 87, Sen, who lives near Harvard with his wife, Emma Rothschild, the Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History, has no interest in resting on his considerable laurels. In addition to teaching one course each semester, either in economics, history or philosophy, Sen is a sharp, frequent critic of contemporary Indian politics. He recently completed a new book, “Home in the World: A Memoir” set for release in July in the U.K., with a U.S. release soon to follow.

Tell me a little bit about your family and life growing in India in the 1930s.

I come from a family with an academic background. My father was a professor of chemistry in Dhaka University, which is [located in what is] now the capital of Bangladesh. My mother had a mixture of professions. She was quite a successful dancer once, but she was also an editor of a magazine that she edited for about 30 years. Her father was a very famous professor of Sanskrit at Visva-Bharati University established in Shantiniketan, which is a small town about 100 miles from Calcutta. I spent quite a lot of time as a child with my grandparents in Shantiniketan when the war was going on with Japan. I studied there from the age of 7 to the age of 17.

They were not particularly strict. They were rather progressive parents. They themselves came from an academic background on both sides. They’d all been to the universities, and even though they had professions of other kinds, not always teaching — my paternal grandfather was a lawyer and a judge — I think they were just interested in academia quite a bit. My father was a natural scientist and a chemist; whereas on my mother’s side, they were much more interested in humanities.

Why were you living with your grandparents and not your parents?

I was with my grandparents because the war was going on at that time between Japan and the Allied forces. The Japanese army came all the way into the eastern side of India from Burma. So that was the reason for me to be not in a big town like Calcutta or Dhaka, but in a small university town where my grandfather was teaching Sanskrit. Japanese bombs would not come down on a university town, but they could come down in Calcutta, in Dhaka. In fact Dhaka didn’t get any bombing at all; Calcutta did get some, but not very much really.

I liked the university town atmosphere. I loved the fact that my school was progressive. It was a coeducational school with an almost equal number of boys and girls. The library was open shelf, so I could go all the time up and down and look at my own books. That’s why I spent an incredible amount of time in the libraries. It’s a kind of life that suited me.

The Visva-Bharati school was established by the Nobel laureate novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, an associate of your grandfather’s who had a skeptical view of Western education. How unusual was the school’s curriculum and approach to education for the era?

It was unusual in many ways, even for it to be coeducational. In fact, my college at Cambridge, Trinity College, was the first single-sex educational establishment I studied at. But it was progressive in many other ways too, in terms of the freedom of choice that the students had. My mother, who went to the same school as me, learned, while in school, judo and other things which girls very often didn’t really do in those days. She also appeared on stage as a dancer. Established, middle-class families often hesitated in India to go on stage, but she did. She didn’t maintain her career as a dancer, though she was quite successful in that, but she stopped it when I was growing up. So it was a progressive school. We didn’t have formal exams and marks. When there were exams, the exam marks were not taken very seriously at all. There was no pressure to work.

When I was six, I did go to a school in Dhaka, in the capital of Bangladesh, which was a missionary school called Saint Gregory’s. That was a very disciplined school and academically quite excellent. So I did go there for a little over a year. And before that, between the ages of three and six, I was in Burma, in Mandalay, where my father had gone for three years as a visiting professor to teach chemistry.

Outside of class, what were some of your passions as a young boy?

I was quite social and spent a lot of time chatting with people. Among activities, chatting with people is quite high on my list. I was a bicyclist of quite an extreme kind. I went everywhere on bicycles. Quite a lot of the research I did required me to take long bicycle trips. One of the research trips I did in 1970 was about the development of famines in India. I studied the Bengal famine of 1943, in which about 3 million people died. It was clear to me it wasn’t caused by the food supply having fallen compared with earlier. It hadn’t. What we had was [a] war-related economic boom that increased the wages of some people, but not others. And those who did not have higher wages still had to face the higher price of food — in particular, rice, which is the staple food in the region. That’s how the starvation occurred. In order to do this research, I had to see what wages people were being paid for various rural economic activities. I also had to find out what the prices were of basic food in the main markets. All this required me to go to many different places and look at their records so I went all these distances on my bike.

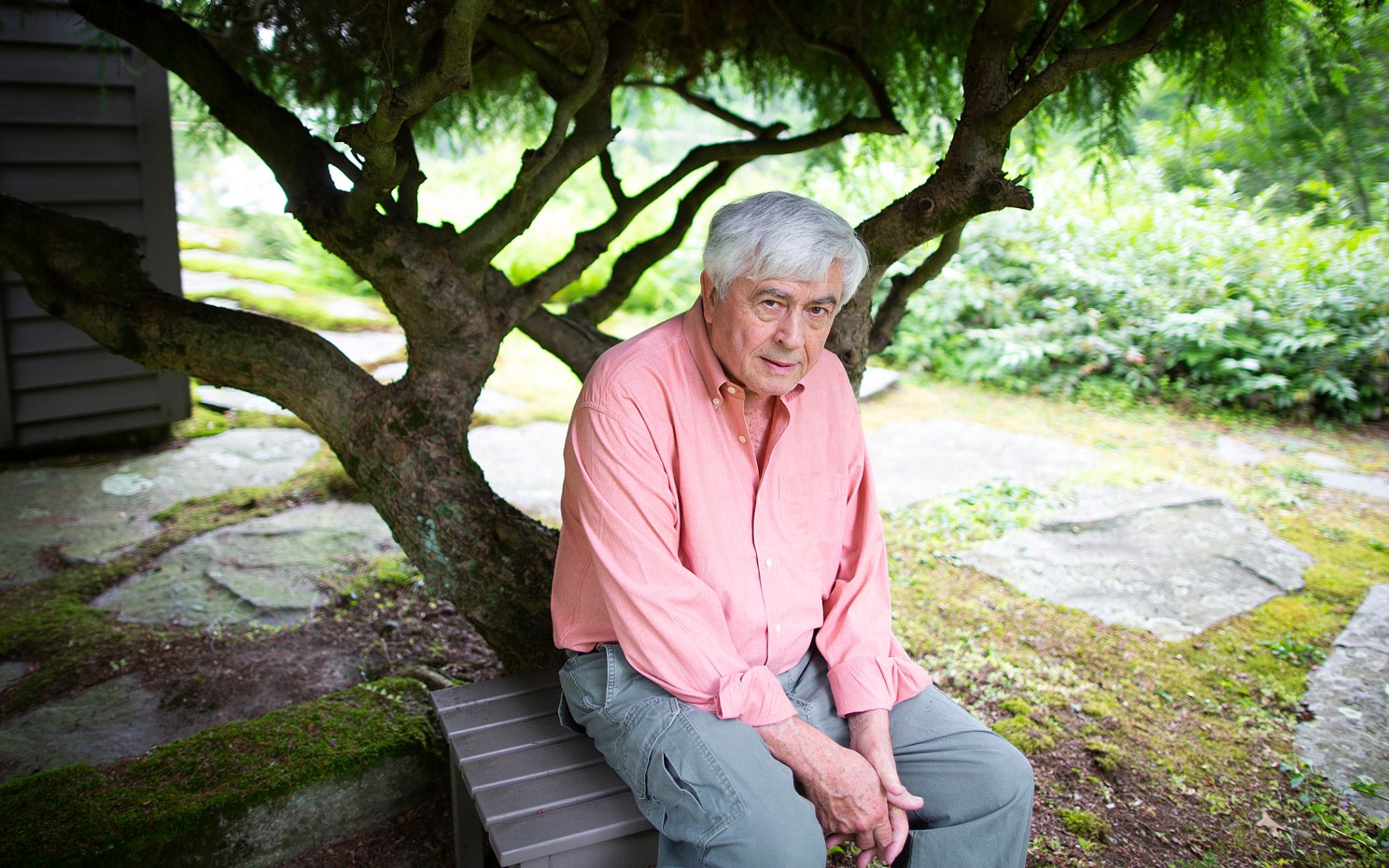

Amartya Sen at Pratichi, Shantiniketan, his home in West Bengal.

Photo courtesy of Amartya Sen

And when I got interested in gender inequality, I studied the weights of boys and girls over their childhood. Very often, it would happen that the girls and boys were born the same weight, but by the time they were five, the boys had — in weight for age —overtaken the girls. It’s not so much that the girls were not fed well — there might have been some of that. But mainly, the hospital care and medical treatment available were rather less for girls than for boys. In order to find this out, I had to look at each family and also weigh the children to see how they were doing in terms of weight for age. These were in villages, which were often not near my town; I had to bicycle there.

You were quite young during a time of tremendous political upheaval and change in India’s history. Violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims broke out before the British withdrew from India in 1947. What do you recall of that time?

The British didn’t do much to stop the Hindu-Muslim riots. In fact, some people took the view that the British were actually encouraging these riots because that made them indispensable in India. So there were a lot of critics who saw the divide-and-rule policy as being the imperial policy.

The violence erupted quite suddenly?

It did. There was very little Hindu/Muslim conflict until about the age 7 or 8 in my life. And then suddenly, it appeared from nowhere, but dramatically, strongly. It took over one’s life almost fully. You couldn’t go outside your home for [fear] of being assaulted. On one occasion, I must have been about 10 or 11, I was playing in the garden when I saw somebody had come in through the outside gates of our compound, a very stricken man who had been clearly knifed in the back, and he was bleeding profusely. He came to the house asking for help and some water. I went running around, getting water, getting my dad to take him to the hospital, which he did, of course. Unfortunately, they couldn’t save him. He still did die. He was knifed by some Hindu thugs. He was a Muslim laborer, therefore, a prey for Hindu thugs, just as the Hindu laborers were prey for Muslim thugs.

I did talk with him a bit while he was getting weaker and weaker. He said with great sadness it was because the children had no food at home that he had to go out to get a little income — so he could buy some food for the children. For that, he lost his life.

While the assailants and victims came from different religions, Hindu or Muslim, the victims were all from the same class, or nearly all. They were poor laborers. Because they didn’t have any shelter at home, it was very easy to break into their homes, very easy to find them on the street, like this person who came to our house for help. Similarly, there would have been Hindu laborers being assaulted by Muslim murderers all over the city. It came suddenly around 1943, 1944, and after 10 years or so, it was gone. India was divided.

Did that experience help shape your later career choices?

Yes, of course, it did. I was particularly involved in violence and premature death. In this case, it came from murder and criminal violence. In some other cases, it came from famines and people dying of starvation or from illnesses associated with famine. So I was concerned with this rather morbid aspect of human life. And then later on in my life, I did some work on that.

Was economics an early interest?

I did not have much interest in economics when I was young. It developed much later. Academically, I was interested in math and Sanskrit and physics.

“There was very little Hindu/Muslim conflict until about the age 7 or 8 in my life. And then suddenly, it appeared from nowhere, but dramatically, strongly. It took over one’s life almost fully.”

What was the appeal for you?

I was reasonably good at math, and I liked doing it, so that was the main reason for doing math. I also liked abstract reasoning. So, along with my interest in reading math from India, where my knowledge of Sanskrit was a great help, I was interested in the early Greek mathematics also as to how, axiomatically, they pursued it.

I was interested in Sanskrit. I liked the language and still do, but I also enjoyed the fact that with my Sanskrit, I could both read great poetry, great novels, great plays in particular, but also great scientific and mathematical writings which were, in ancient India, in Sanskrit.

When the Nobel committee after you get your prize asks you to give two mementos or two objects connected with your work, I chose two. One was a bicycle, which was an obvious choice. And the other was a Sanskrit book of mathematics from the fifth century by Aryabhata. Both I had a lot of use for.

You were 23 when you got your first position teaching college-level economics in 1956. How did you become interested in teaching?

I was very interested in teaching from the time when I was a student. I used to run a night school. We set up a night school for the tribal children. There were a lot of local tribal people who had no schools at all around their homes. So some friends and me started these night schools. There were three or four of us who were interested in that, and we used to go there from about the time of sunset — when we could work with lanterns. And on the weekends, on Sundays in particular, we did day classes. I taught math, mostly. And there were others who taught English and Bengali.

You come from a highly educated and privileged family. How did you first become fascinated with the economic conditions and choices of the poor?

I was always interested in the economics of the poor people. I was interested in the lives of people who were very short of income and prosperity — how do they cope? Mainly, as I ran the night schools, the people I was mixing with were students from the tribal villages in the neighborhood. They were very poor. And we very often talked about how they earned their income or how their parents earned their income, and how do they manage, how do they plan their future, and all that. So I got interested in that. And I didn’t think I would have much money to invest, and I didn’t. But I did think I might have a great deal of interest in the politics of poor people. So that played a big part in my getting involved with that kind of economics.

Your interest in politics started while you were a college student in Calcutta?

No, I think earlier. In Shantiniketan it started. The family was quite political because nearly everyone was interested in getting rid of the British Empire. My father’s cousins, my mother’s brother and cousins, they were all getting arrested under what the British called “preventive detention.” That doesn’t mean they’re charged with any crime, and the government didn’t have to establish that they have committed any crime. But it’s a preventive detention that unless you detain them, they could cause crime. That was the idea. So I think among my parents’ cousins, I had about seven or eight people who were periodically in and out of “preventive detention.”

What were they worried about your relatives doing?

Basically, because they were writing essays saying why the British ought to go. I remember from the time when I was between seven and eight [that] I went with my grandfather and grandmother, who were trying to plead with this Indian, but British, civil service officer, asking, “Why have you kept my son in prison?” To which this officer said, “Because he writes anti-imperial essays and op-eds in newspapers and magazines, and we have to make him stop doing it.” So my grandmother said, “But he has never committed any violence.” And this officer said, “No, and indeed, that is not the reason why he is in prison. But as soon as he stops writing anti-British raj essays, we would be happy for him to come out.” I was very impressed by this conversation [laughs], but I didn’t fully understand what else was going on.

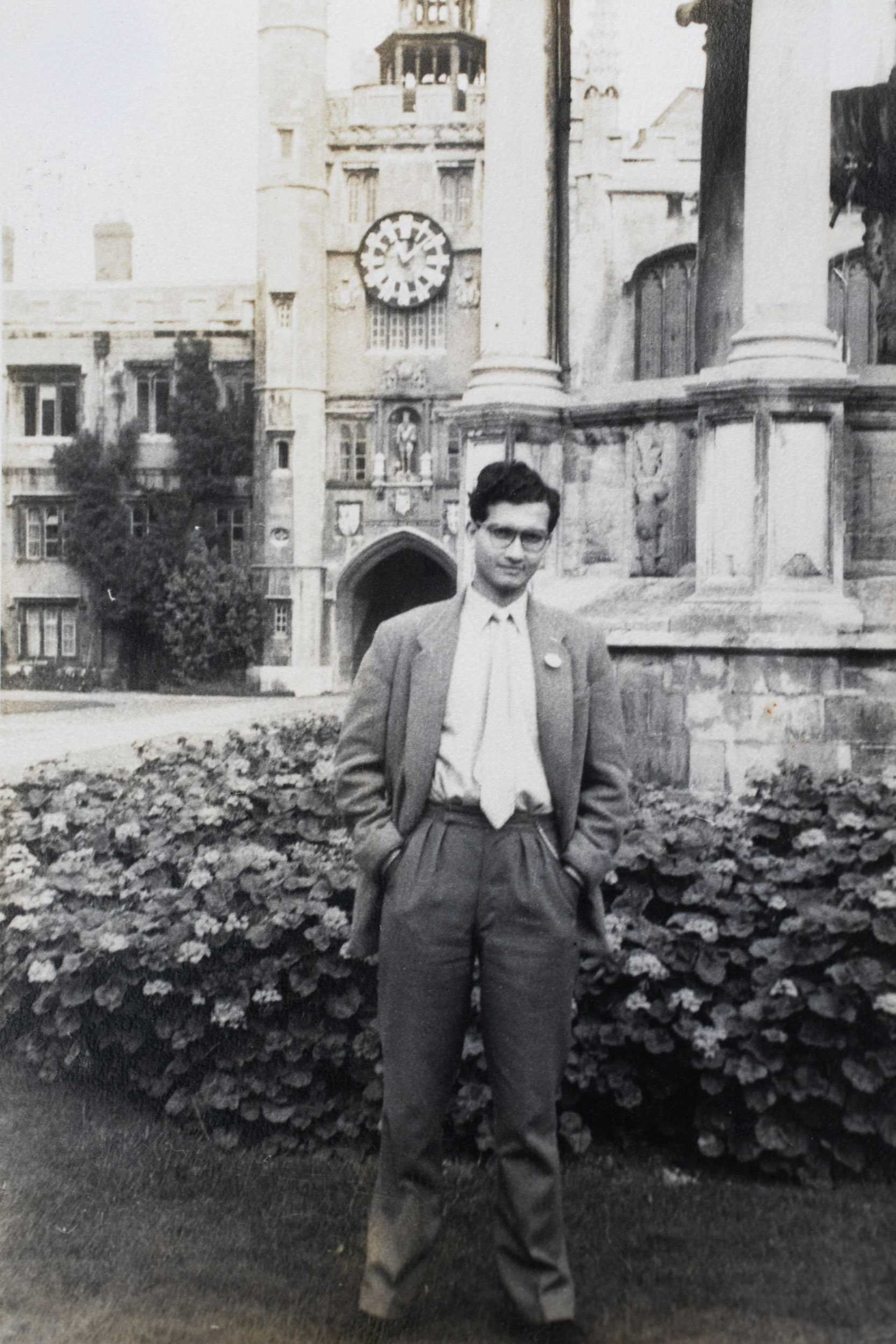

Amartya Sen at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1958.

Photo courtesy of Amartya Sen

After you graduated from Presidency College in two years, you went to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge in 1953. Tell me about that decision.

My Calcutta degree was a BA degree, and the Cambridge people treated it as the “part one” of the BA degree. And I think they were right. It’s not a very high-level degree, but I had that, and I’d done well. So when I went to Cambridge, they said, “OK, you can do our three-year degree in two years.” So I did another BA in two years in Cambridge. And by that time, I was also doing relatively advanced economics of various kinds. There was a kind of gulf, because in Calcutta, I was quite used to doing rather technical economics, and suddenly, I found myself attending classes in Cambridge with people who had done very little technical economics.

You set out on an 18-day voyage by boat from India to England. Was attending Cambridge something you had always dreamed of doing?

It was originally my dad’s idea. When I was a student in Calcutta, I had what they call squamous cell carcinoma in my mouth. I had radiation treatment, and it destroyed a lot of the bones in the mouth. So it was a hard time. The doctors gave me a 15 percent chance of living for five more years; that’s all. But when I recovered from it, I think my father thought that it may be a good thing for me to go abroad. He was a teacher, but he had just about enough to support me for three years in England. Initially, I didn’t get in. But when I eventually got in, he was able to pay for it, including the boat trip.

Did Cambridge’s reputation in economics at the time draw you there?

That’s right. There was a combination. I was going to do economics. At that time, Cambridge had the reputation of having the best department of economics in the world. That was one reason. It may not have been true, though, but people believed that. But I also was interested in mathematics, and particularly in the college I chose to go to, in Trinity College, there had been people whose influence was still there, like Bertrand Russell, [Alfred North] Whitehead, [Ludwig] Wittgenstein, and others who were interested in the philosophy of mathematics. I was interested in that. And I also had a lasting interest in politics, and there were a number of good thinkers on the left in Cambridge.

Who were some of the people advising you back then?

One mentor was an Italian economist, Piero Sraffa. He was my director of studies, as they call him, so he was in charge of my education in Cambridge. And I got on very well with him. There was Maurice Dobb, who was a Marxist economist, and probably the leading Marxist economist in Britain at that time. And then there was Dennis Robertson, who was a conservative economist, but very amiable and friendly. They were great mentors of mine. I spent quite a bit of time chatting with them, and they were indulgent of me. Sraffa and I used to go out for walks after lunch on a regular basis, almost every other day. He liked chatting with me, and I did like chatting with him.

What were the big economic debates happening at that time?

Among the conventional ones, there was a good debate still about whether unemployment could be kept away by Keynesian policies — by government expenditure and planned action. The Keynesian remedy for unemployment was one of the major debates on that subject. This was about a decade after FDR here, and, in economic theory, John Maynard Keynes in England had made a big difference to the thinking about unemployment — that you could eliminate it.

But I was also interested in the poor people’s economics, [people] who had nothing to sell except their labor because they don’t have any assets. How could they survive? And what can you say about their economic studies? And what can you say about the issues being discussed very much now here, like minimum wages? That also made me interested in such subjects as the labor theory of value, because labor theory is very important for those who have only labor to offer to the market and hardly any assets. So I was generally interested in poor people’s economics. There was quite a lot of debate going on, and I liked joining in, which I did.

How would you describe your politics then?

Definitely much left of center, but very keen on liberty and pluralism. That is, I thought the left had much better things to offer — this was true also in Calcutta, much earlier, before I came to Cambridge — had much more things to say. But what I disliked is that often they would regard liberty and giving people the freedom of choice — First Amendment, for example — to be a kind of bourgeois luxury, which I didn’t think it was at all. So I opted for the left, but with a lot of interest in liberty and freedom.

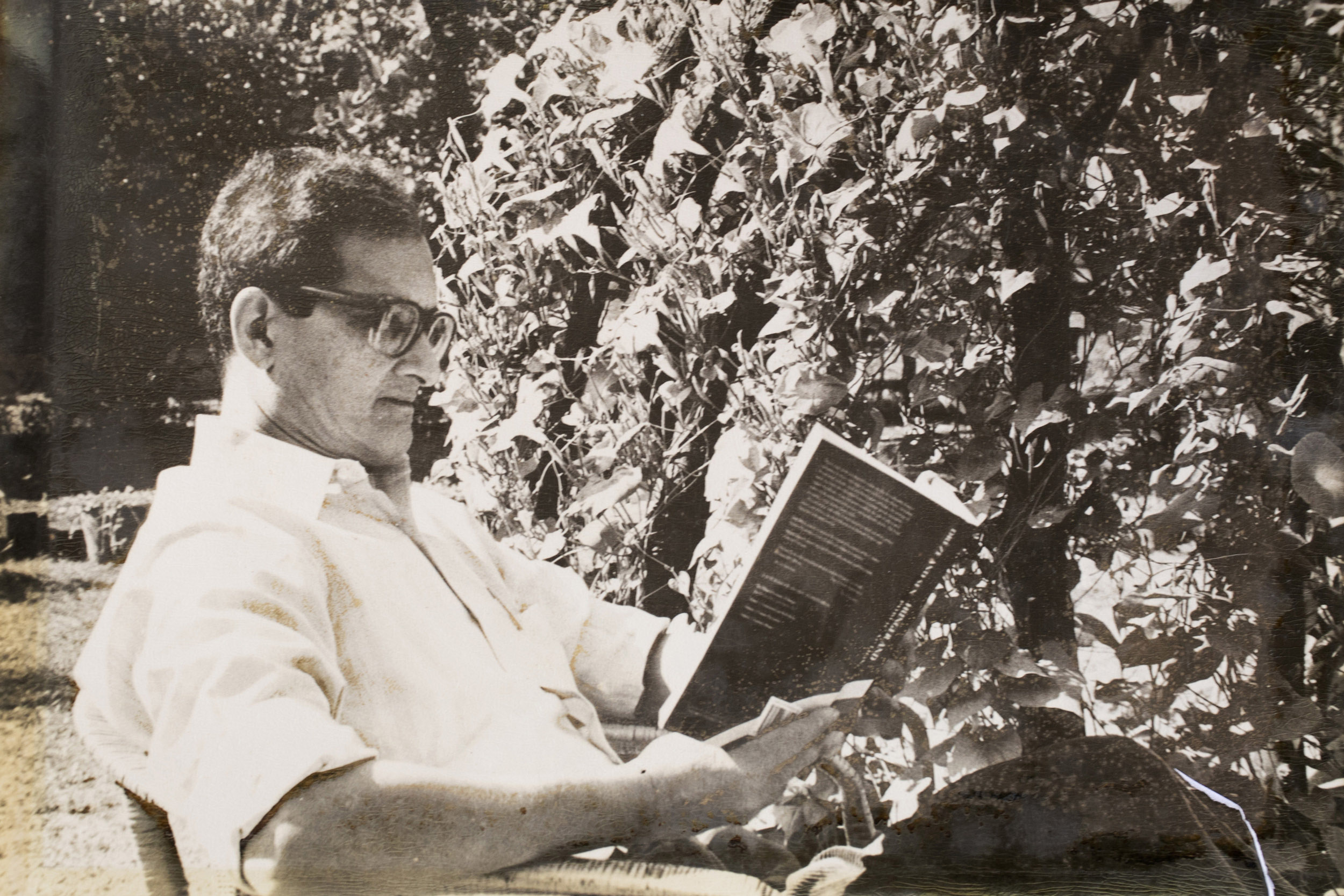

Amartya Sen reading in the garden at Pratichi.

Photo courtesy of Amartya Sen

So much of your work has been pioneering. Before you had become established, did people suggest that your career would advance faster, perhaps further if you focused on more conventional areas of economics?

I didn’t spend too much time thinking about it, because first of all, as far as my small life is concerned, I was not having a difficult time. The college [had] elected me to a Prize Fellowship. For four years, I had no obligations. I could do what I liked, and I got an assistant professor’s salary, or what in Cambridge would be a lecturer’s salary. So I was doing quite well. My only problem was that I didn’t often have people working in a similar area who I could chat with about my own work. For that, I had to do some traveling. And I decided quite early in my life, when I had just finished my degree in Cambridge, that I will, every fourth year, go to America for a year and be a visiting professor. I was at MIT for a year, and I went to Stanford. I went to Harvard and then Berkeley. I was traveling and really enjoyed the interactions very much indeed. So it worked out all right.

You left a prestigious teaching job in India to return to Cambridge to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy. Why philosophy?

I was always interested in philosophy. I had studied on my own a certain amount of philosophy, including Indian philosophy. When I became reasonably skilled in Sanskrit, I could read the old philosophical documents in Sanskrit. I was never really interested in religion very much, so these were non-religious subjects, especially epistemology and ethics. And I really enjoyed doing them, including philosophy of mathematics. I fully enjoyed doing them. But when the college suddenly said, “Now, for four years, you can do what you like. We’ll give you a salary,” I said, “This is a really good chance to do some philosophy systematically,” which I did.

Who were some of the thinkers that influenced you in those days?

When I was in school, I was particularly involved in the philosophy of an Indian philosopher called Aryabhata. He was around 500 AD. He was a mathematician and an astronomer and a philosopher. He was an expert on such things as the diurnal motion of the Earth, rather than the sun going around the earth. He was interested in the theory of eclipses. He was interested in the fact that since Earth is a round object, being up when you were on one side of the Earth was the opposite of being up on the other side of the globe. He was concerned with the relativity of your position compared with other positions on Earth you could occupy. Aryabhata and his follower Brahmagupta were also interested in gravity, in explaining why small objects are not thrown away as the earth rotates.

I spent quite a bit of time in my school days studying these Sanskrit puzzles, as to why this happened. These were mostly anti-religious, but rationalistic thinking. So they remained a part of my interest. When I came to Cambridge, they got gradually transferred into modern mathematical philosophy, like that of Russell and Whitehead and Wittgenstein and so on. But I also, by then, was getting interested in ethics and epistemology. In ethics, John Rawls was a big influence on my thinking. I read quite a bit of “Mathematical Logic,” particularly [Willard Van Orman] Quine, who was also here, and Hilary Putnam. These are people I read with great admiration and profit. I was reading more and more of their writings as I advanced. And eventually, I did some work that was influenced by their works.

You focused on economic inequities between women and men when it was a relatively uncommon thing to do. What prompted you to examine those issues?

I was particularly struck by the fact that even in my school, which was a very progressive school, that the achievements of girls and achievements of women in general seemed to receive far less appreciation and acclaim than men’s work did. I also thought that some of [my women] classmates almost seemed to understate their own claim to fame because they didn’t want to generate a sense of nervousness among the men as to whether they are keeping up. And as a result, they end up understating their reasons for recognition. So I spent a bit of time thinking how we could make it more natural that women should be less modest. That was one of the reasons. The other is, I encountered all these big problems like missing women (that there are fewer women than there would be had they received equal care). Women do have a pretty bad deal in life, and that seemed to me to be an immediate reason for working on the issues of gender inequality.

I’m planning to do a book on gender. There should be one in about a year or two. There are so many different problems people get confused that I thought I might put together the problems that make up gender disadvantage. It will draw on prior research, but there will be a number of new things in it.

“People have given up hope that I might retire. But I like working, I must say. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve never done, when I think about it, work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.”

Your work seems to address, either directly or indirectly, issues of social justice. Where does that come from?

I’ve always been interested in issues of social justice, even in my school days. And it continued when I was in Cambridge. Earlier I talked about Piero Sraffa mainly as an economist, but he was interested in philosophy, too, and he was very concerned with issues of justice. And then, because of John Rawls, social justice became very easily a subject for me to talk about and decide where I disagreed with Rawls, which I did. But I would not have been able to do any of this work without Rawls. With Rawls, I could say, “Well, yes, Rawls is important for me, but I disagree here. There, I disagree.” The other influence was Hilary Putnam. But underlying all that was my interest in social choice, the mathematical reasoning involved. Kenneth Arrow, who essentially invented the subject, was, of course, a big factor in my choice of work. I taught a class with Ken Arrow and John Rawls in ’68-’69. I was visiting here at Harvard. Arrow was then on the faculty of Harvard for some years, and Rawls was very established at Harvard. So the three of us together, we did a class on justice and social choice, which was quite fun. I remember, while flying to a meeting in Washington, my neighbor on the plane asked me what did I do? I said, “I teach in Delhi, but at the moment I’m visiting Harvard.” I told him that I’m concerned with justice and social choice involving aggregation of individuals’ disparate views. And he said, “Oh, let me tell you: There is a very interesting class taught by Kenneth Arrow, John Rawls, and some unknown guy on this very subject. You should check it out!”

I really enjoyed it very much because they had such excitingly original minds. They invented questions that others had not thought of and dealt with them, both Rawls and Arrow did. I had been under their influence even before I came to Harvard, but of course, it was wonderful to be able to teach a class together.

Arrow’s groundbreaking “Social Choice and Individual Values” (1951) was published when you were a first-year undergraduate. How influential was it to your thinking then?

It was a transformation for me. I knew different people had different values and preferences, and so the question could easily arise: What should the society do given the variety of views that we happen to have? But the fact that one could get a systematic discipline out of it had not occurred to me. I was only 17, I guess, then. But once it occurred to me and I could see what Arrow had done, I couldn’t resist taking a serious interest in the subject. The literature then was quite limited. Now, of course, the literature’s exceedingly vast.

You’ve seen the conventional wisdom, as it were, evolve in economics on a number of fronts. Have you reconsidered any of your own thinking over the years?

Well, indeed yes. It happened even in social choice theory, too. That is, initially I was convinced, as Arrow had been, that the problem is arising from the fact that we are asking society to have an organized, systematic preference. Whereas society cannot have such a preference because it’s not an individual. Persons do have such preferences. So instead of asking, how do we go from individual preferences to a systematic social choice based on a social preference, we could ask the question: How can we go from individual preferences to any social choice so that in every group of alternatives from which to choose, there will be an alternative which gets to be a majority choice by the people over every other alternative in that group. The prevailing intuition was that there should be no impossibility there. I was increasingly convinced that this itself would lead to an impossibility. So, in this respect, I changed my mind on how the impossibility in “the impossibility result” of Arrow comes about.

Amartya Sen leaving his office at the Harvard Center for Population and Development, 1999.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Looking back, when did you feel like you had made your mark in the field? Was it the publication of “Collective Choice and Social Welfare,” which is widely-considered a foundational text?

I have not reached that point yet. I’m working hard to get there! [laughter] “Collective Choice and Social Welfare” is the book that made me think I understood the subject, namely social-choice theory. I hadn’t earlier on had the sense of being in command of the subject. By the time I wrote “Collective Choice and Social Welfare,” I did have the sense that I could do all those things and that I could lecture on them. And indeed I did — everywhere. I did it in Delhi. I did it in LSE, London School of Economics. I did it here in Harvard, when I was visiting here for one year, 1968. In addition I was extending the results already known. I enjoyed those classes. I still enjoy doing problems in social choice theory. I teach now here with Eric Maskin and Barry Mazur, [Gerhard Gade University Professor], and we do cover social choice theory from time to time. That interest is unlikely to go away for me.

Is there more out there you’d still like to explore?

There are a number of problems which I would love to do. Some of them are things that would make a difference in the world a bit more. For example, we can move from poverty to security and see what help we get from social choice theory. Further there are quite a few other analytical problems involving mathematical logic that still interest me. Who knows? I may think of new problems.

In 1998, you were awarded the economics Nobel for your many theoretical, empirical, and ethical contributions to the field. Yet it doesn’t seem to have been the career capstone for you that it often is for other laureates. You remain as busy as ever writing, working, traveling, teaching. Why?

People have given up hope that I might retire. But I like working, I must say. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve never done, when I think about it, work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.

I’m 87. Something I enjoy most is teaching. It may not be a natural age for teaching, I guess, but I absolutely love it. And since my students also seem not unhappy with my teaching, I think it’s a very good idea to continue doing it.