Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘When you see death all the time, you go into this mode of increased energy and sharper focus’

Harvard Chan School AIDS pioneer Max Essex shares lessons from the frenzied search for answers about a once-mysterious ailment

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

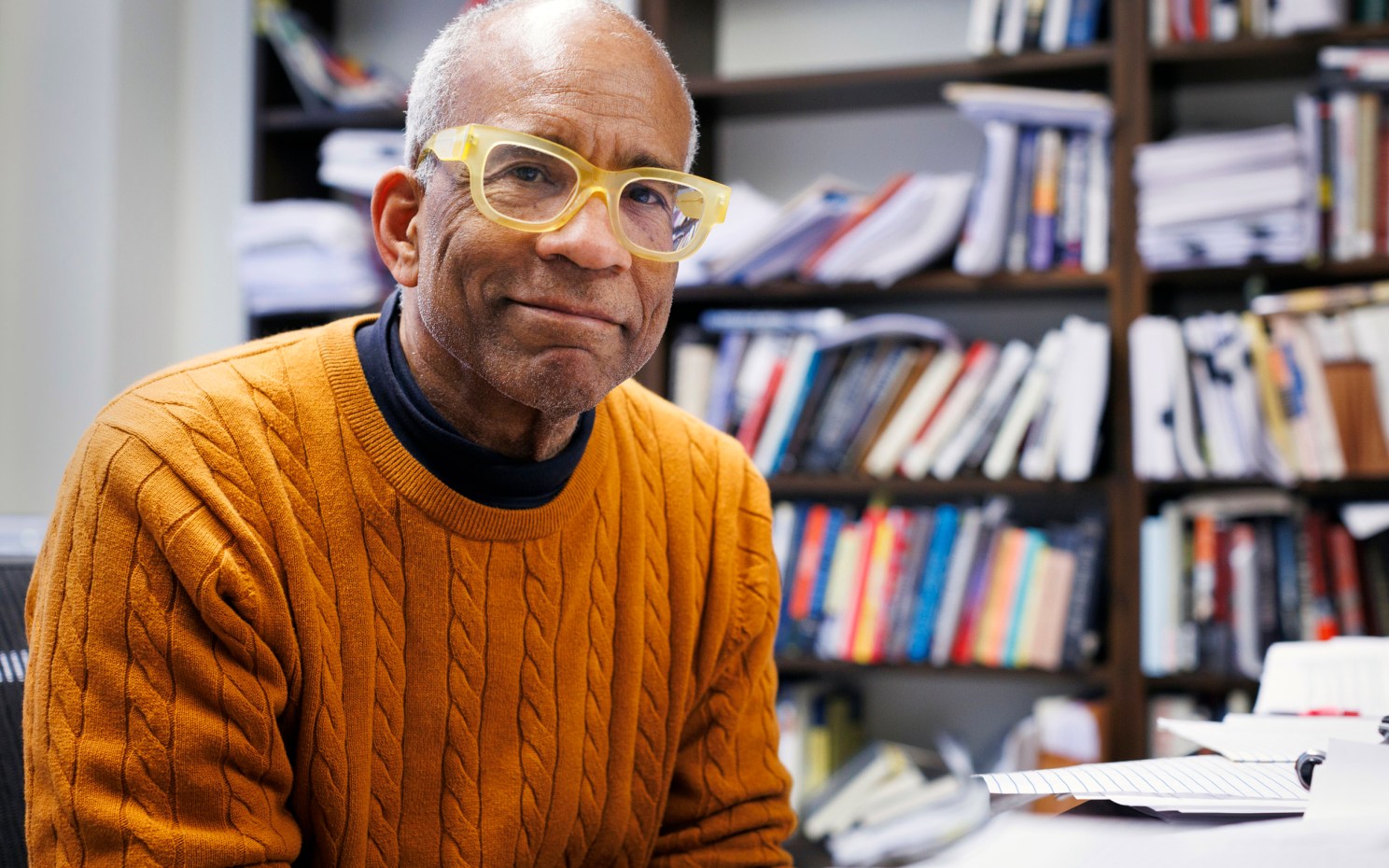

During an earlier pandemic that even today is only slowly relaxing its grip on the globe, pioneering AIDS researcher Myron “Max” Essex was one of the first to propose that a retrovirus was the cause of AIDS. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health virologist’s work shed light on the nature of HIV, led to development of an HIV blood test, and later focused on fighting the global pandemic at its heart — in southern Africa. As the head of the Harvard AIDS Institute, now the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health AIDS Initiative (HAI), Essex established the Botswana Harvard Partnership, a collaboration between the University’s AIDS scientists and the government of Botswana. Though HIV/AIDS has become a chronic condition for many — 23.3 million were on antiretroviral drugs at the end of 2018 — work remains to be done. Some 770,000 died from HIV-related causes in 2018, and nearly 15 million of the 38 million infected worldwide are not receiving drug treatment, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Essex, who in February 2019 became the Mary Woodard Lasker Professor of Health Sciences, Emeritus, sat down with the Gazette to talk about his career, share his thoughts about the challenges ahead in the fight against HIV, and offer lessons learned to a new generation of students.

What are your thoughts on COVID-19 in light of your experience with HIV? Is there a major lesson to be learned?

I think there are quite a few lessons to be learned. One is we’re never fully prepared for these things because they emerge from nowhere as zoonotic infections and we don’t study the natural environment of viruses enough in lower species or do sentinel surveys of people that have more frequent contact with these feral, wild species. HIV/AIDS came from subhuman primates — multiple times — and was amplified rapidly via air travel. COVID presumably came from animals in the market in Wuhan [China]. It amplified with people and air travel. It’s just amazing how little we know about the breadth of these viruses in animals that could interact with people. We totally ignore those issues.

The second lesson is the importance of international cooperation for understanding and surveillance. The entire world structure breaks down if you don’t have good cooperation.

There are lessons at every level. With HIV/AIDS, we learned an awful lot about how to make good drugs. We learned that mixing different drugs will compensate for the mutation rate of RNA viruses, and COVID is an RNA virus. Eventually, we had drugs that were so well designed that it was hard for the virus to mutate around them. This is probably a bias from HIV, but my own feeling is that it’s going to be easier to make drugs against COVID-19 than to make a vaccine that’s highly efficacious. It might even be easier to take drugs prophylactically for high-exposure people.

The COVID-19 vaccine development target seems very aggressive. Are you concerned at all that a vaccine can be developed in a year or year and a half?

I think with all the effort that’s going into it, I would say there probably will be something, perhaps with 30 percent to 60 percent efficacy. It could be generally available, at least in the West, for high-risk groups, within two years. That’s my best guess. But they’re not going to have long-term safety [data]. It’s possible a lot of people will get injected with something that hasn’t really been proven for efficacy.

Why don’t we look more closely at HIV and AIDS, which you spent much of your career fighting. How do you view the pandemic now? Do you feel your work has had an effect?

I would say that I’m absolutely amazed that we — speaking for all AIDS researchers in the world over the last 30, 40 years — have been as successful as we have in preventing new infections, recognizing the total lack of any success whatsoever in making a vaccine. If you had asked me — and I’d venture to say most other AIDS researchers in the 1980s would agree — if we would have been able to control this epidemic without a vaccine, I would have said, “No.” We have succeeded, for the most part, in controlling it without a vaccine.

What has made a vaccine against HIV so difficult? You personally have tried a couple of approaches and others — well-funded pharma companies included — have as well. There’s been a lot of work on this.

Absolutely. I got in in the first wave with quite a few others, to do vaccine research, try to make a vaccine, and we tested a couple. I would say, though, to give myself a little credit, that we also got out sooner than many others because we recognized it wasn’t going anywhere. The reason is that the virus is prone to mutations that can evade immune responses. It was a never-ending challenge because the virus was always a step or two ahead and able to overcome [any vaccine] through selection and successful replication — evolution, if you will. What we didn’t remotely appreciate at the time was that drugs [used for treatment] would be able to overcome that evolution, overcome the mutations HIV was evolving toward drug resistance. The utilization of multiple drugs to target the virus all at once meant it couldn’t mutate fast enough to survive. That made us appreciate that it was easier to beat the virus by drugs than by vaccines.

You have had an interesting path, from veterinary school to heading a Harvard AIDS lab, to work in southern Africa. How did you get interested in science/biology/virology/veterinary medicine to begin with? I’ve read that you were born in Rhode Island. Did you grow up there?

Yes. I’m not sure there’s much that’s remarkable. Neither of my parents went to college. My father didn’t even go to high school. He was, I guess you’d say, a lower-level businessperson — a sporting-goods salesman and such. And my mother was mostly stay-at-home, though I think she worked a little as a secretary when I was younger.

Brothers and sisters?

One sister, Cynthia, three years older. She did go to college and worked most of her life at Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown. She ended up as head of the lower school there, a position she retired from five or so years ago.

Did your parents emphasize education, since both of you went to college?

They encouraged it. I think part of my motivation was I liked sports. I played basketball in high school, thought I was better than I really was and thought I could play basketball in college — at the University of Rhode Island — but wasn’t good enough to do that. Then I found that science was interesting.

“I’m absolutely amazed that we have been as successful as we have in preventing new infections, recognizing the total lack of any success whatsoever in making a vaccine.”

What year did you graduate from URI? And was it a science degree?

[In] ’62, and zoology — I think it was agricultural science — but it was really microbiology, essentially immunology. I decided I wanted to go into medical research and not clinical practice, and decided that it might be faster and easier to do that by combining a research degree with a veterinary degree. I doubt if I came to that conclusion on my own, but it was clear that Michigan State would give me free tuition to do both in what was a six-year program.

Did you have dogs, cats growing up?

Both, but I don’t think that was a motivation, and I didn’t really know any veterinarians. At that time, I was interested in immunology and cancer research, and it seemed that a lot of progress was being made looking at virally caused cancers in animals. There was a lot of attention by then on leukemia viruses in mice. Even then, there was the beginning of research on viruses in cats and cattle, and an appreciation that animal models were a good way to understand human cancer. That really carried the day for a decade or two. It was not until the 1980s, with gene sequencing and genetics and gene transfer and all those things, where people decided that looking at natural models of cancer and other diseases in animals maybe wasn’t needed as much. You had ways to do more direct experiments in people through genetic manipulation and through epidemiologic design and trial.

So you went from URI to Michigan State to study veterinary medicine and microbiology?

Yes. It was intended to be a six-year program, but I was opportunistic. I enrolled in a six-year program to do a degree in veterinary medicine and a Ph.D. I did the degree in veterinary medicine, and about the time I was in the middle of the Ph.D., my major professor left the university to move to Ohio State. And there was confusion about whether I’d switch to somebody else there to complete the Ph.D. or move with him to Ohio State. But I was in a position where if I just took the veterinary degree I could go elsewhere and get a postdoctoral stipend to do a Ph.D. I did, to the University of California, Davis. They said I could finish it in less than three years, and I did in about two and a half. So I ended up getting a stipend of $7,000 or something to complete the Ph.D. there. I didn’t feel an obligation to stay with Michigan State to complete the doctoral degree because the major professor left, but there were other factors too. I was married at the time. My wife was a veterinarian. And she was interested in doing an internship in Davis, so it made sense in that way too.

“I could imagine that if my whole career was 20 years out of phase — if I was 20 years younger — that I wouldn’t have been in a position to do much work of the same level of importance on AIDS.”

So you got your Ph.D. in microbiology and then did a postdoc in Sweden?

It was really in virology, with some immunology, but the official label is microbiology. I took a position for two years at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Then I left after about a year and a half because I had some good job opportunities.

Was that in ’72, when you came here to the Chan School?

Yeah.

When did you start working on feline leukemia, which proved so important to your later insights on HIV?

In California at Davis. That was my Ph.D. thesis. I selected Karolinska for my postdoc because, first of all, the guy whom I worked under, George Klein, was a world leader on how the immune response could control cancer infection or cancers that were associated with viruses. He was doing that with both Burkitt’s lymphoma in people, which some of his earlier work — and that of others — had already linked to Epstein-Barr virus, and with mouse models of leukemia virus that were in the same general category as the cat virus I worked on. He was happy to have me come because it would expand the work he was doing into other systems.

You worked on feline leukemia through the ’70s, work that led to a vaccine. When did you first hear about AIDS?

I can’t tell you the exact time. But the first publications were in ’81 in New England Journal of Medicine. I certainly heard about it then. Anybody who was in infectious disease areas, viral diseases, bacterial diseases, or anything like that, heard about all these young men who were dying of some epidemic thing that wasn’t understood at all.

It seemed to be due to immune suppression? Was it clear to you from the start that something unusual was going on?

Oh, yeah. I remember having discussions with people about it and then getting seriously involved in doing the research in 1982.

What specifically did you begin looking into?

I started looking into the possibility that a retrovirus that was related to the human T-cell leukemia virus that [National Institutes of Health (NIH) researcher Robert] Gallo had discovered in the late ’70s was involved. The other important component was a paper that we published on the cat system in 1974 or ’75 about how the feline leukemia virus caused more deaths in cats by immune suppression than by leukemia. That could be interpreted as happening because the cats died from pneumonias and other things before they actually died of leukemia. That was the first clear evidence that a virus — any virus — caused immune suppression in any mammalian species. This was long before AIDS and the recognition that there was an infectious form of immunosuppression in people. That played into why I thought a retrovirus candidate should be considered as the cause of AIDS. Gallo had discovered that this human leukemia virus was a retrovirus, like the cat virus, and we had shown that a retrovirus could cause immune suppression in cats. We then addressed the question of whether or not the first human retrovirus, the T-cell virus he discovered, caused immune suppression in people, even without AIDS. And then, when AIDS came along, we said, “Suppose there’s an even more virulent and monstrous retrovirus. What if there’s an even more vicious one that’s the cause of this AIDS in people?” Gallo, as recently as last November, credits me as coming up with the same hypothesis that he did: that a retrovirus was a logical cause for human AIDS.

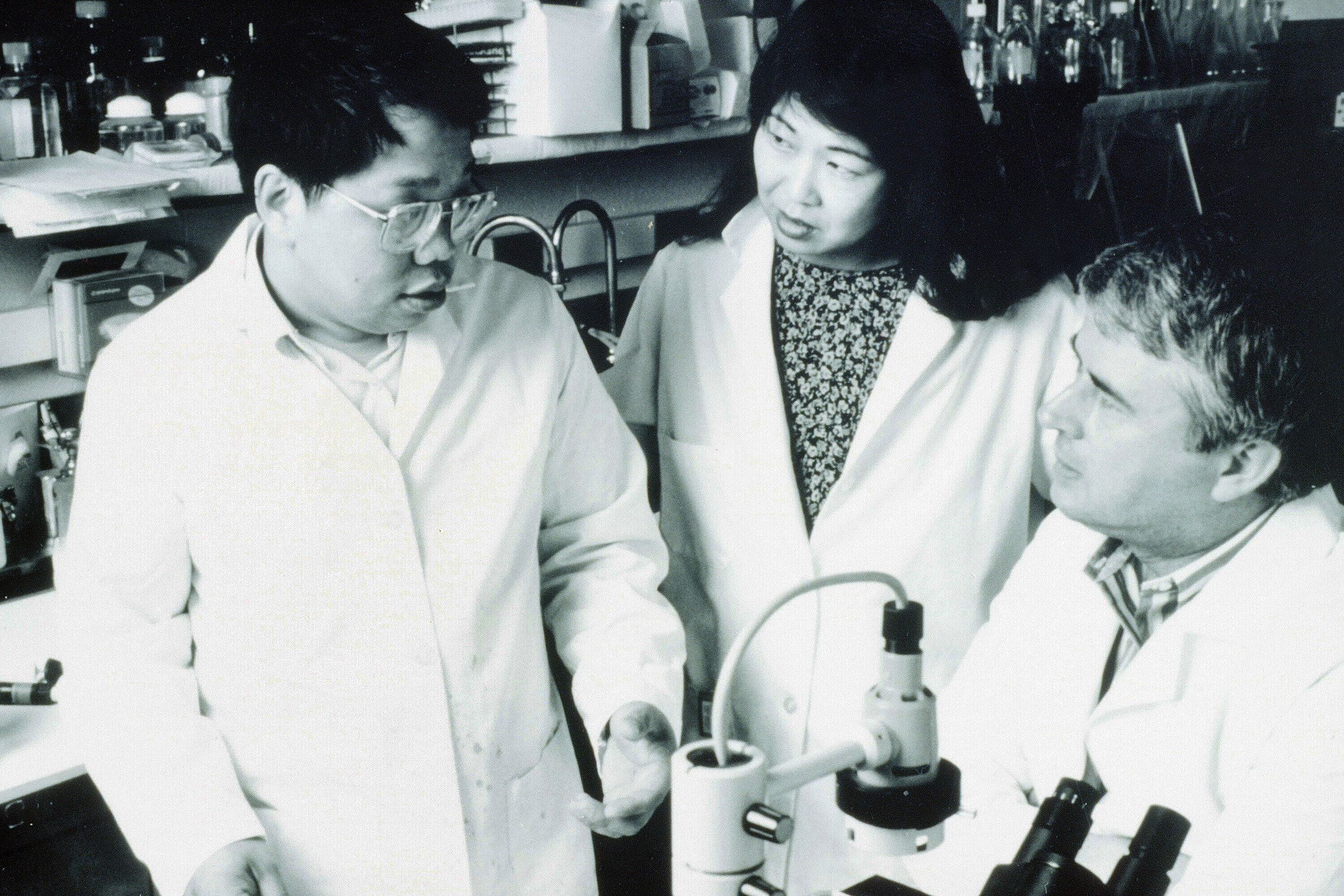

Max Essex (right) with Phyllis Kanki, today the Mary Woodard Lasker Professor of Health Sciences (center), and Tun-Hou Lee, emeritus professor of virology, all of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, during the push to understand AIDS and HIV in the 1980s.

Photo courtesy of Max Essex

How well did you know him?

I knew Gallo before that, but in 1982 we were brought together in two or three different workshops. One I remember specifically was called by the NIH, with the CDC [Centers for Disease Control], in Bethesda [Maryland]. It brought people together to think about how to find the cause of this new epidemic. They brought maybe 20 or 25 of us who were infectious-disease people, mostly virologists, and another 20 or 25 who didn’t believe it was infectious and had hypotheses about how behavior was causing it, and another bunch — 20, 25 — that had totally different hypotheses.

We were all put in different sections to think about it. One group of us focused on infectious origin, Gallo and I on retrovirus, but others thought it might be a herpes virus or another kind of virus or other microorganism. There had been hypotheses that Kaposi sarcoma was caused by a specific virus even before that, and it ended up proven to be caused by a herpes virus. But then there was another group who thought that it might just be due to drugs, because there were amyl nitrate-butyl nitrate type of poppers and other drugs used for sexual performance in gay men’s groups. They were pushing the hypothesis that that might be the cause. And there were other groups who believed it was due to rectal sex and people being exposed to semen and other tissue antigens by different routes and generating high levels of antibodies in some mysterious autoimmune kind of way.

Did that change your and Gallo’s course of research at all?

It certainly caused both of us to devote a lot of attention to looking at materials from AIDS patients, yes.

And when did you become certain it was a retrovirus?

Well, we had the first evidence by very late 1982 and published in April or May 1983 in Science that there was a weak cross-reactivity with a human retrovirus, HTLV-1, in about a third of AIDS patients from whom we got materials from the CDC. That same issue of Science was the one that had [Luc] Montagnier’s paper [for which he would win the 2008 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for identifying HIV] in it.

What was the difference between your two papers?

He had two patients, and he had electron micrographs, and we didn’t. Gallo had a couple of papers in it too, and we also had a cat paper in it. Once Science magazine knew we had the results, they asked if we would agree to publish them in the same issue with the others, one month behind, so they could write editorials and all that stuff. Anyway, Montagnier’s paper has electron micrographs and that, in the end, was what carried the day and made the difference. He also talks about the cross-reactivity with HTLV-1 that he found. We had a different approach where we had serology from many more people but no electron micrographs. Then in 1984, a year later, Gallo had the conclusive evidence — I would say — that it was clearly the virus we then called HTLV-3 that caused AIDS. Two or more years after that people started calling it HIV.

After that, did you immediately begin looking for surface proteins on the virus? Because discovering GP120 came after that, which led to the blood test for HIV.

The Nature paper in November ’84 was the first publication that defined GP120 and said it would be the best component for blood tests. In 1985, we had sequenced — nucleic acid sequenced — data to match the GP120 to the place in the virus that it originated.

“How could we not put every ounce of energy we’ve got into it, if it’s going to make the difference in an important result that would save people’s lives?”

Key dates

And when you were looking for GP120, did you understand the potential impact of a blood test — hemophiliacs, early on, were a big population at risk of AIDS from blood transfusions — plus diagnostic tests and things like that?

We published a paper on hemophiliacs in ’84, I think. And we were able to do all that because the test was very similar to the test we developed to look for feline leukemia virus infection in cats. We used much of the same technology. It was more advanced and sophisticated because it was seven or eight years later, but it was remarkably similar in principle and from the standpoint of epidemiologic survey.

I read a piece from the late ’80s about the work on AIDS, including yours, here at Harvard. You expressed a sense of urgency about the disease then, and many were predicting doom if we didn’t respond quickly enough. Looking back, did we respond fast enough, or was the calamity that happened in southern Africa in the 1990s what you were worried would happen?

What I was worried would happen in the late ’80s did happen in southern Africa, certainly, and East Africa to a significant extent. The epidemic in Africa was in Central and West Africa first and then in East Africa next and in southern Africa last. And in southern Africa, it was more virulent for reasons we still don’t totally understand, though we understand part of it was due to a different strain of HIV — HIV-1C — and perhaps the genetic characteristics of the people, for which we’ve identified a couple of genetic alleles. But whatever it was, the epidemic really didn’t peak there until sometime at the very end of the 1990s through the early 2000s. And by that time, it was already under control to some extent in most other places. It also plateaued at a much higher level in southern Africa. In 2005, something like that, all of the countries that had prevalence rates of infection above 10 percent — and a dozen or so did — were in southern Africa.

And Botswana had the world’s highest rate?

It did for a while. They were surpassed by Swaziland, now called Eswatini, three or four or five years ago, which was probably in part because Botswana was by then doing a lot of “treatment as prevention” more effectively than Eswatini.

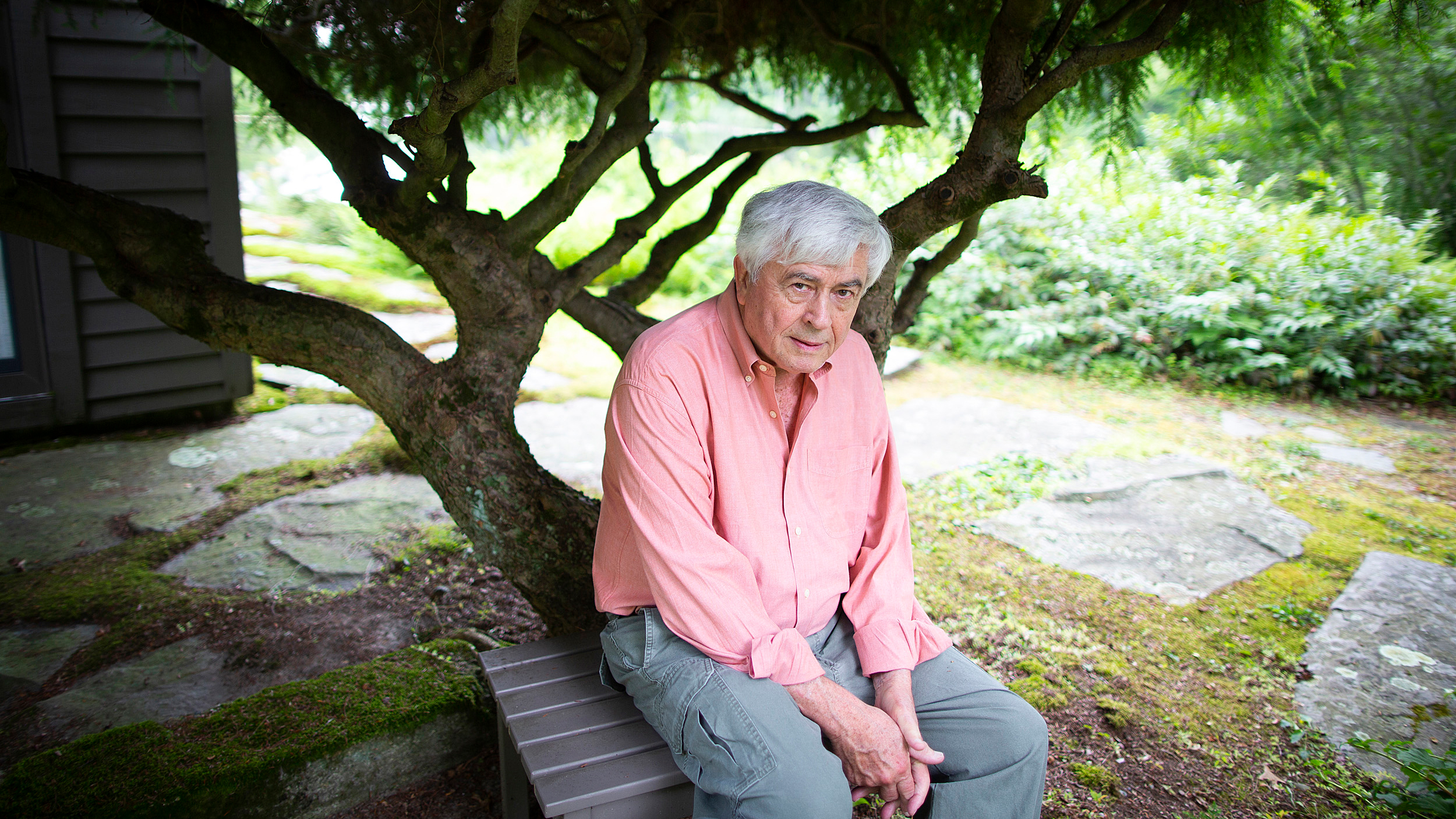

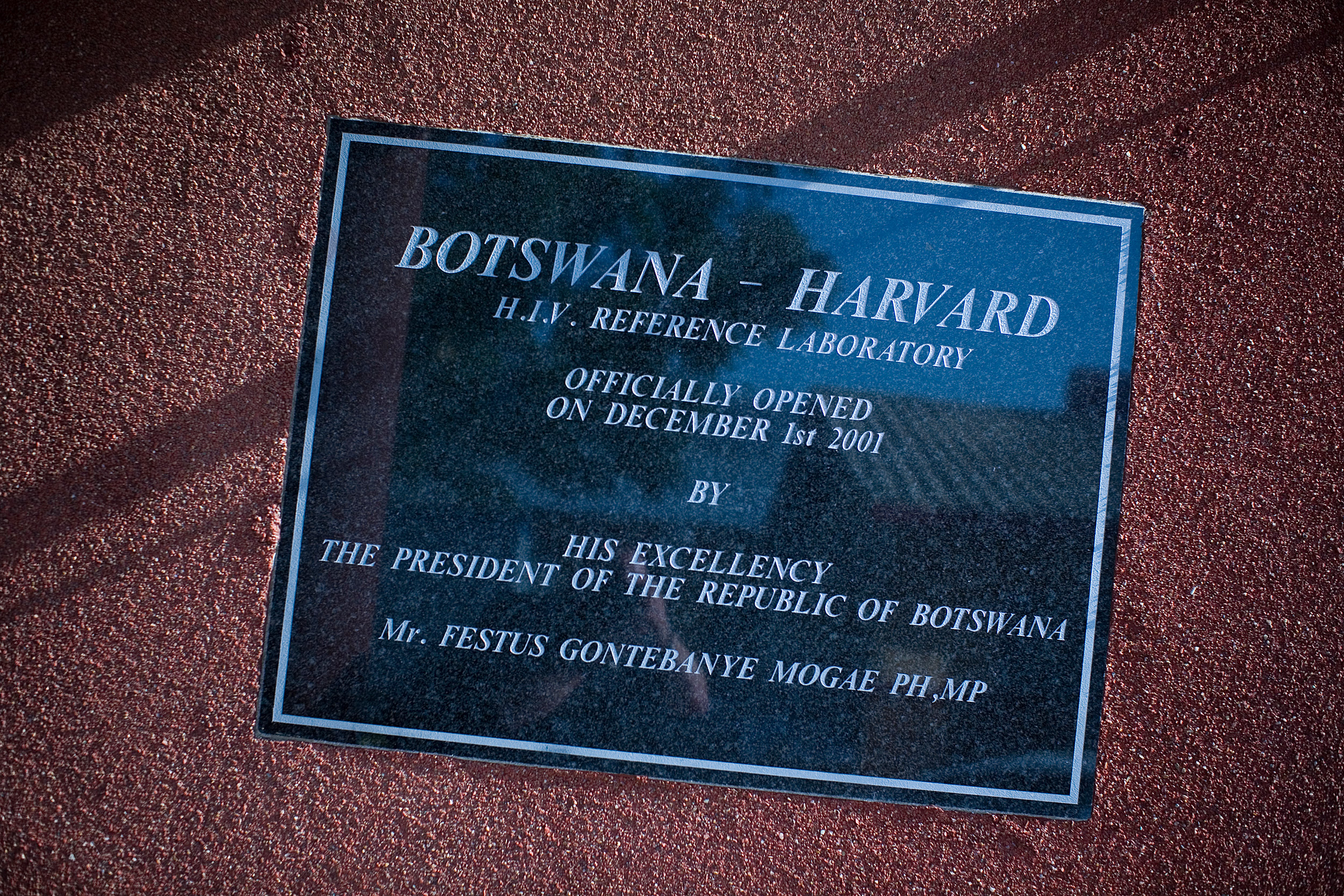

Essex walks near the Botswana-Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory, which opened in 2001, while the facility was under construction on the grounds of Princess Marina Hospital in Botswana’s capital of Gabarone. Dedication plaque below.

Photos above courtesy of Max Essex

The Botswana Harvard Partnership was created in ’96 and the lab opened in 2001. How long have you been working in Botswana and did you know then that was the epicenter of the HIV pandemic?

Nineteen ninety-six was my first visit to Botswana, and yes I knew that southern Africa was where the action was occurring. All the indicators were there, and it seemed that you could learn a lot more a lot faster about why this virus was getting transmitted faster there, and whatever else you wanted to test. At that time, we still had hope for vaccines. But [even with] drugs — anything — you could make faster progress with human trials if rates of transmission were faster and fractions of the population getting infected were higher.

So I consulted with a personal friend who knows Africa well — Maurice Tempelsman in New York, who was in the diamond business — and asked him, “Where in southern Africa would you recommend setting up a program, where we could have good interactions with the government, could get a lot of collaboration, and be able to test these concepts that we have?” He recommended Botswana because of the stability of the government and his knowledge that they were more eager and willing than many other leaders in southern Africa to take HIV seriously. He set up a meeting to introduce me to then-President [Ketumile] Masire, who invited me to visit the country. So the first time I went — which was the summer of 1996 — was to consult with Masire about what could be done to control HIV there. We went over and got 18 or 20 samples from HIV-infected people on that first visit.

Did you find then that the virus in southern Africa was different from that in the U.S.? Did we know at that point it was HIV-1C rather than 1B?

Yes, we found that out then.

You started out with a scientific mission, but through your engagement in Botswana, knowing officials there and people working at the Botswana Harvard Partnership and in its lab in Gaborone, did it become more personal?

Yes, certainly over time it became personal. I felt such a warm welcome from people there — both government officials and collaborators — physicians and medical personnel, some of whom became scientists. On one of the first visits, then-President Masire invited me and my wife, who happened to go with me on that trip, into his home for a regular family dinner. He had his children there and maybe even some grandchildren and us, and that’s all. So there was a very warm feeling between us, and I had the same relationship with the health minister and the people that he introduced me to, and the president who followed him, who was his vice president, [Festus] Mogae. They made me feel like I was one of them and part of the country. I wanted to help in any way I could, which was really through doing applicable research that would help them address questions of how to prevent this massive epidemic from killing more people and infecting others.

In January 2008, Joseph Makhema, director of the Botswana-Harvard Partnership, speaks with an assistant inside his office at the Botswana-Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory in Gaborone, Botswana.

Harvard file photo

Your work in years subsequent to that resulted in findings important for discordant couples — where only one partner is infected — to stop mother-to-child transmission, drug treatment as prevention. You even helped design the national AIDS training program for health care workers. It seems that your presence and the partnership’s presence has had enormous impact. Do you ever think about the number of lives that that your work and the work of the people around you have saved?

Well, I think it made a big difference and saved a lot of lives. I haven’t done — nor will I do — the mathematical analysis to say how many, but I think it really did save a lot of lives. I guess the greatest value came from our recognition of which research would have the most immediate application and could save lives right away. For example, the first thing we did in Botswana was the prevention of mother-infant transmission, where it would actually be easy to quantify how many lives it saved rapidly, because then it’s kids who didn’t get infected versus the expected ratio who would have been infected. We did that first because we felt that, based on some earlier things we were doing in Thailand, that lives could be saved within a year or two or three, not 20 years from now with a hypothetical vaccine.

Did the epidemic come home to the lab? Did you lose lab workers, colleagues?

Absolutely. I’ve been to a lot of funerals in Botswana. When we started the lab over there, one of the first four people we hired died of AIDS. I remember being very moved by that. Quite a few in our project were infected with HIV. Some were successfully treated and others I went to funerals for. The title of the book I wrote with Unity Dow, who’s now minister of foreign affairs — “Saturday Is for Funerals” [published in 2010] — was because everybody had so many funerals in the early 2000s that there was no time for anything else, like weddings, on Saturdays.

With such a high percentage of the population infected and people in their prime dying — teachers, lab workers — did you ever feel like the tragedy going on around you was too much? How did you manage working while surrounded by the suffering?

I think you go into a frame of mind almost like an oncologist or a preacher, someone who deals with death all the time. Obviously, it’s different if you know the person, but when you see death all the time, you go into this mode of increased energy, I guess, and sharper focus — maybe in the same way that people do when they’re fighting a war. I certainly felt the same kind of thing in the 1980s, early in the epidemic, along with other AIDS researchers. We all felt kind of a bond with each other and a need to collaborate and to share data with each other and run the kinds of experiments that would give us immediate answers that would help patients already infected and direct them as to what they could do. I think that’s just a mentality that you go into when faced with that kind of situation. And I was faced with it in the early to mid- and somewhat later 1980s. Then we felt there was some progress and we could view it with a little different perspective because, in the U.S., people’s lives were being saved. Then, when I got to Botswana in 1996, it was like being back in the early to mid-1980s in the U.S.: You’ve got to do something that can be used fast.

You discussed feeling that you were at war, more or less. I read about your work habits during the 1980s — getting up at 4:30, in the office by 5:30. Is that accurate? And was that because of the situation or have you always worked like that?

A little of both. I certainly did that then, but I got up at 4:30 today. The difference is, at the time, I also stayed until 8 or 9 or 10 looking at data, and I don’t do that anymore and haven’t for many years. So the early rising part is probably a little bit of a misinterpretation of my commitment because I’ve done that anyway.

“The most important thing is to ask a lot of questions, think about the problem, formulate hypotheses, and run those hypotheses by colleagues.”

Staff at the Botswana-Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory process blood from patients in 2008.

Harvard file photo

Where did that urgency come from? Was it simply an intellectual understanding of the stakes, or did you have friends early on who died of AIDS?

Well, in Botswana, it came more from seeing so many people die and recognizing how overwhelming it was. A quarter of the population was infected —35 percent of women. But at both stages, it was definitely from a feeling that we — my group — could find an answer that would make a great difference in this epidemic and for these people. And we can find it sooner if we work harder. Some — those on the most cynical side — would say we were only doing that because we wanted attention and fortune and fame. But we would say, “How could we not put every ounce of energy we’ve got into it, if it’s going to make the difference in an important result that would save people’s lives? If it’s going to change the face of the epidemic this year rather than next year?” We were definitely feeling that our results, really, were so important that how could we not work harder and get them out sooner? And by get them out, I mean we had to do all the work to publish them in the best places. We were publishing papers one right after the other in Science and Nature and all the most competitive journals at that time. And they were making a difference in the epidemic. After the first one or two or three, and you know the results you’ve got for the next one or two or three, how could you rationalize not going into a frenzy to get them out faster? It’s part of being in science and practical medical research at such a time, when everything comes together to make you realize that you’ve got the answer. And maybe like people building a bomb during the war — how could you not devote as much time and energy to it at that time?

Do you remember a moment when it dawned on you: “Holy crow, I might be able to find an answer to this?”

Yes. I remember several moments. I remember moments when that occurred that we felt we knew the cause. And I remember moments when that occurred that we felt that we had a blood test that people needed to use. And I remember moments when we felt, even later, that we knew how to prevent mother-infant transmission in a practical way, and we had to get that out in a way that people would believe us, which usually means by publishing in a very high-level journal with adequate data and controls and all that stuff.

Essex (right) with former Botswana President Festus Mogae during a talk about AIDS and the future of Botswana at the Harvard School of Public Health, 2009.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

You were married and raised kids during all this work. How important has your marriage been to your career?

Very important, I would say. I met my wife — I can’t even remember which summer it was — in either ’63 or ’64. We were both students on a research project in Mexico organized by the Pan-American Health Organization. They were tracing the potential northward migration of Venezuelan encephalitis virus. And it did come eventually to Florida. She was a veterinary student at Cornell at the time. We met in Mexico because they offered summer fellowships to both veterinary students and medical students. We met there, coming from different schools, and spent the 10 weeks or whatever it was in southern Mexico, got to know each other, and fell in love.

Did she work as a veterinarian?

Yes, all her life.

Is she still practicing today?

A little bit. She’s mostly in retirement, but she does relief work in a practice now in Westwood, which is derivative of a practice she was in in Norwood for 40 years.

There’s been a lot of discussion in recent years about the pressures on junior faculty and the need to have, at the very least, a supportive spouse. How was family life in those early years?

Well, she did a lot. Our two daughters are 50 and 46 or 47 now. It was obviously tough and hectic. We did have some help from other people, and both daughters went to prep school and lived there. But still it was a lot of work for her to do. And I couldn’t have done what I did without her, certainly.

It seems one characteristic of your work all along has been collaboration — in the ’80s with Gallo and other scientists here, and in the ’90s and into the 2000s with the government of Botswana and the health institution there. Can you talk a little bit about the importance of collaboration to your work?

It’s absolutely important and essential, really, because you need people to think seriously about your hypotheses and give you objective evaluations. You need people to contribute their own disciplines because often the best solution to any practical research question is one that requires expertise in different disciplines. It’s long since been impossible for people to be expert in virology and immunology and statistics and epidemiology and pathophysiology and everything else. So you have to be in a mode of constant learning from others. And you’re in that mode if you have a serious scientific collaboration with others who come from backgrounds where they have very different perspectives than you do.

What would you say to students looking at your career and wanting to have a similar impact on an important problem?

The most important thing is to ask a lot of questions, think about the problem, formulate hypotheses, and run those hypotheses by colleagues. I think many people doing research, especially early in their careers, tend to collect and generate data — today’s equipment and techniques allow you to get more data than you can understand. But it’s still important, I think, to start out with hypotheses. Think more about what creative solutions you can bring to the question. But it’s also true that some people are in the right place at the right time in very challenging situations. I couldn’t imagine that I would have had the same approach to solving important parts of AIDS if I hadn’t had the perspective of immunosuppression in cats. And I could imagine that if my whole career was 20 years out of phase — if I was 20 years younger — that I wouldn’t have been in a position to do much work of the same level of importance on AIDS.

What do you see as being the future of the AIDS epidemic? What’s the next big thing?

The next big thing is, I think, getting down to very low levels of infectious people, which is what UNAIDS is seeking with their 90-90-90 treatment target [by which 90 percent of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90 percent of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 90 percent of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression by 2020], or 95-95-95. I shouldn’t just put them off as “them,” because I’m actually on the Science and Technical Advisory Committee, which is advising UNAIDS. We’re likely in the next 10 years to see a time when new infections with HIV are very uncommon and the epidemic phase of AIDS will be over. I think some have interpreted that as “the end of AIDS,” meaning that there’s only sporadic cases here and there. But there’s going to be hundreds, if not thousands, of cases in the U.S. for the next 25 or 50 years and proportional numbers in the rest of the world.

Interview was edited for clarity and condensed for space.