Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘If you stay the same in everything you do as things around you are changing, eventually you’re going to hit a wall. You just have to adapt and evolve and change.’

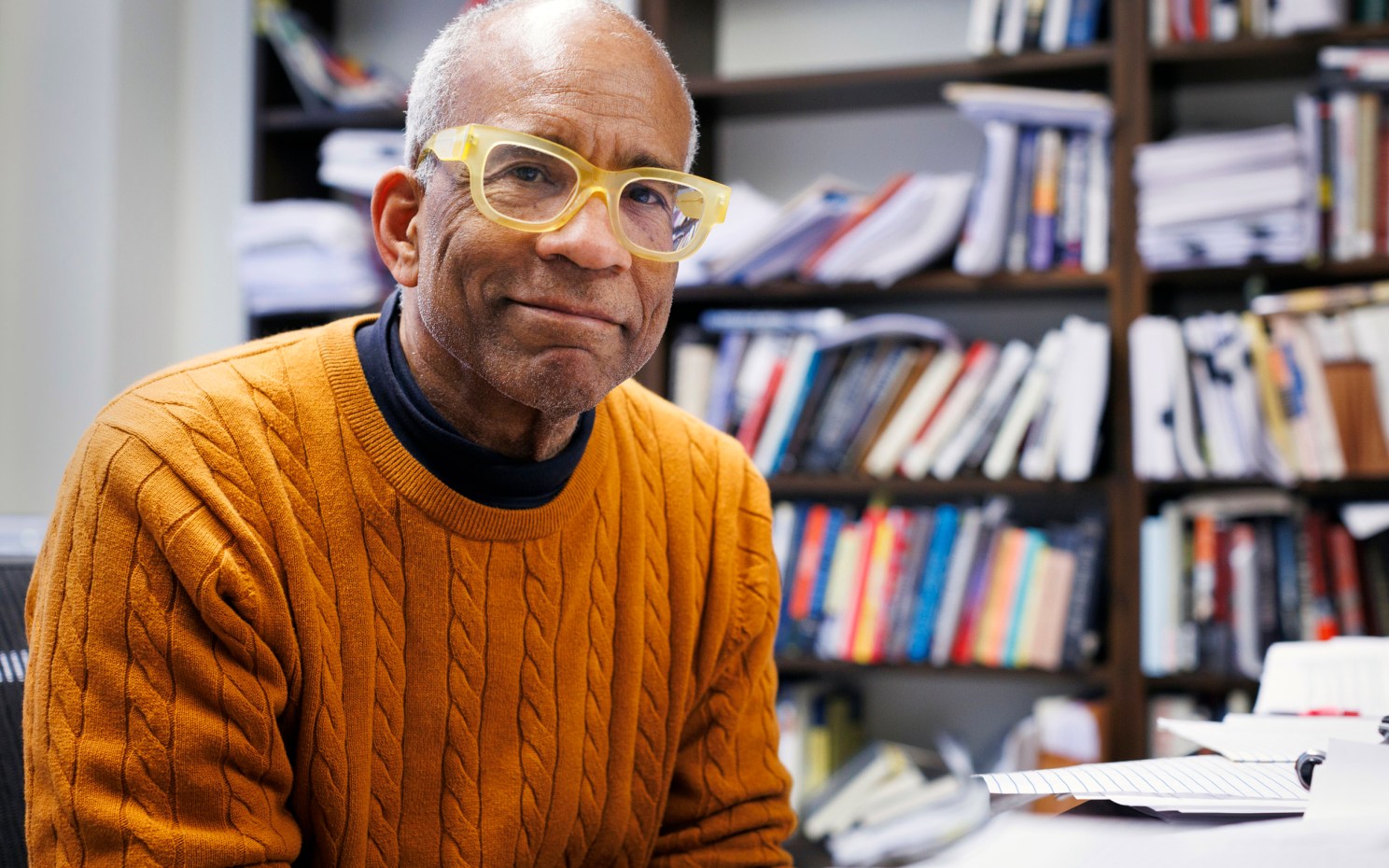

Harvard’s Tim Murphy, winningest coach in Ivy history, on trusting his gut, ‘Murphy Time,’ other life lessons

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

Head football coach Tim Murphy has led the Crimson to nine Ivy League championships, three unbeaten seasons, and a 186-83 record in 28 years, becoming the winningest coach in Ivy League history last fall. Not bad for a guy who almost didn’t become a college coach — in fact, for someone who wasn’t even planning to go to college (never mind graduate school). Murphy’s life has had a few twists and spins — married for more than three decades, he still hasn’t been on a honeymoon, and not for lack of trying.

Born in 1956, Murphy grew up outside of Plymouth in Kingston, Massachusetts. Besides Harvard, Murphy has coached at Brown University, the University of Maine, and the University of Cincinnati. With a combined 218-128-1 record, Murphy has earned a reputation as one of the premier coaches in the NCAA. He won the inaugural Ivy League Coach of the Year honor in 2014, has served as president of the American Football Coaches Association, and was a three-time finalist for the Eddie Robinson Award for the top coach in the football conference.

The Harvard Crimson 2022 season starts at Harvard Stadium Friday against Merrimack College. Murphy, the Thomas Stephenson Family Head Coach for Harvard Football, sat down with the Gazette to reflect on his long career and share his thoughts about lessons he’s learned. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Last year, you became the winningest coach in Ivy League history. What did that mean to you?

It means that we’ve done a pretty decent job here as a team. It takes a village to be successful in a competitive venture, and we’ve had a great village for a long time, especially realizing that this village is ever-changing. There’s always a graduating senior class; there are always assistant coaches who move on. What it comes down to is we’ve done a good job recruiting and developing student athletes and coaches here. We’ve had some really outstanding ones. That has all allowed us to compete at a very high level, consistently, for a good amount of time now.

When it comes to student-athletes, what do you remember most about the ones you remember best?

It’s hard to express to people who haven’t been around it. There’ve been so many students who through almost sheer character have become so much better than their talent level may have indicated. Ryan Fitzpatrick ’05 is a great example. His character along with his considerable ability was such that he transcended the level everybody thought he would be at. He went from not just good at quarterback to arguably the best quarterback in Ivy League history. His character was such that he kept finding ways to get better and better and better. We’ve had a lot of student athletes just like that, whether it’s one of the 31 athletes we’ve had sign NFL contracts or students who’ve gone on to other careers.

How’s it feel when you see players or coaches go on and have success, whether it’s in the NFL or elsewhere?

It’s a lot of pride — pride that these really great people have managed to have success in their lives. To see those guys be able to continue to climb and reach their goals makes you really happy for them. That’s what we’re all about. Graduating our kids as students and as student athletes and to help them get where they want to be in their lives.

You grew up in Kingston, Massachusetts, about 35 miles south of Boston. Did you always want to be a college coach? What was your childhood like?

I had a working-class background. My mom was pretty much responsible for being the caregiver and breadwinner. I was the first and only one in my family to ever go to college. Quite frankly, as a young high school student, I didn’t see being a college coach on my horizon.

Do you remember how you started playing football?

I do. We would play sandlot football. That’s all it was. It was pure as it could get.

You didn’t see yourself going to college. What changed?

The simple reason I am where I am today is that my high school coaches changed the trajectory of my life. It might have been my junior year in high school, my head football coach and my high school basketball coach cornered me in the hallway and said, “What are you doing when you graduate?” I said: “I don’t know, probably join the Marines.” They looked at each other. Basically, they said: “Shut up, son. You’re going to college.” They empowered me and made think I was a lot smarter than I thought I was. I ended up getting a partial scholarship at Springfield College, playing as a linebacker, and doing really well in school. I actually got my master’s degree while playing. It was the first year the NCAA allowed it.

You jumped to coaching after graduating in 1978. How did that happen?

My coach empowered me. Howie Vandersea was my head football coach at Springfield, and after my graduate year of playing I told him that I definitely want to be a coach and that it was what my life’s work was going to be. He helped me get a job as a graduate assistant at a Division I school, Brown University. I only got paid $800 for the year. I ended up in the off-season working in an extrusion mill at the Union Camp Corp. in Providence, Rhode Island. I worked hard enough and smart enough that Brown offered me a better job the year after as the assistant varsity coach. I did well enough that when Brown head coach Bill Russo got the head coaching job at Lafayette College, he hired me as defensive-line coach. It’s kind of how it goes in our business.

When you were so adamant about going into coaching while at Springfield, did you know then that you wanted to be a head coach?

Not then, no. To be honest, I was hedging my bets because the probability of that happening, especially at a young age, was statistically impossible. My backup plan was to get my M.B.A. at a business school. Then, all of a sudden, that became my primary plan.

Obviously, the M.B.A. didn’t happen.

It’s on hold. I had taken free courses at Boston University when I was assistant coach there and then at the University of Maine. During that time at Maine, I had applied to business schools, and I ended up getting into the University of Virginia and the Kellogg School at Northwestern, which was the No. 2 business school in the country at the time. At that point, I had invested so much extra time in my studies while coaching that I had actually tendered my resignation at the University of Maine because I was going to be moving to Chicago for Northwestern.

About six weeks after I tendered my resignation, the head coach job opened at Maine, and they offered it to me. I was actually a bit conflicted. I’d worked so hard to get into really quality business schools. I was surprised to have gotten accepted, and I’d already told Northwestern, I’d attend. In fact, I’d already put down the deposit. I asked Northwestern if they would defer me for a year. They initially said no, but I convinced them to just give me a year, and I’ll get this head coaching thing out of my system. That was about 35 years ago.

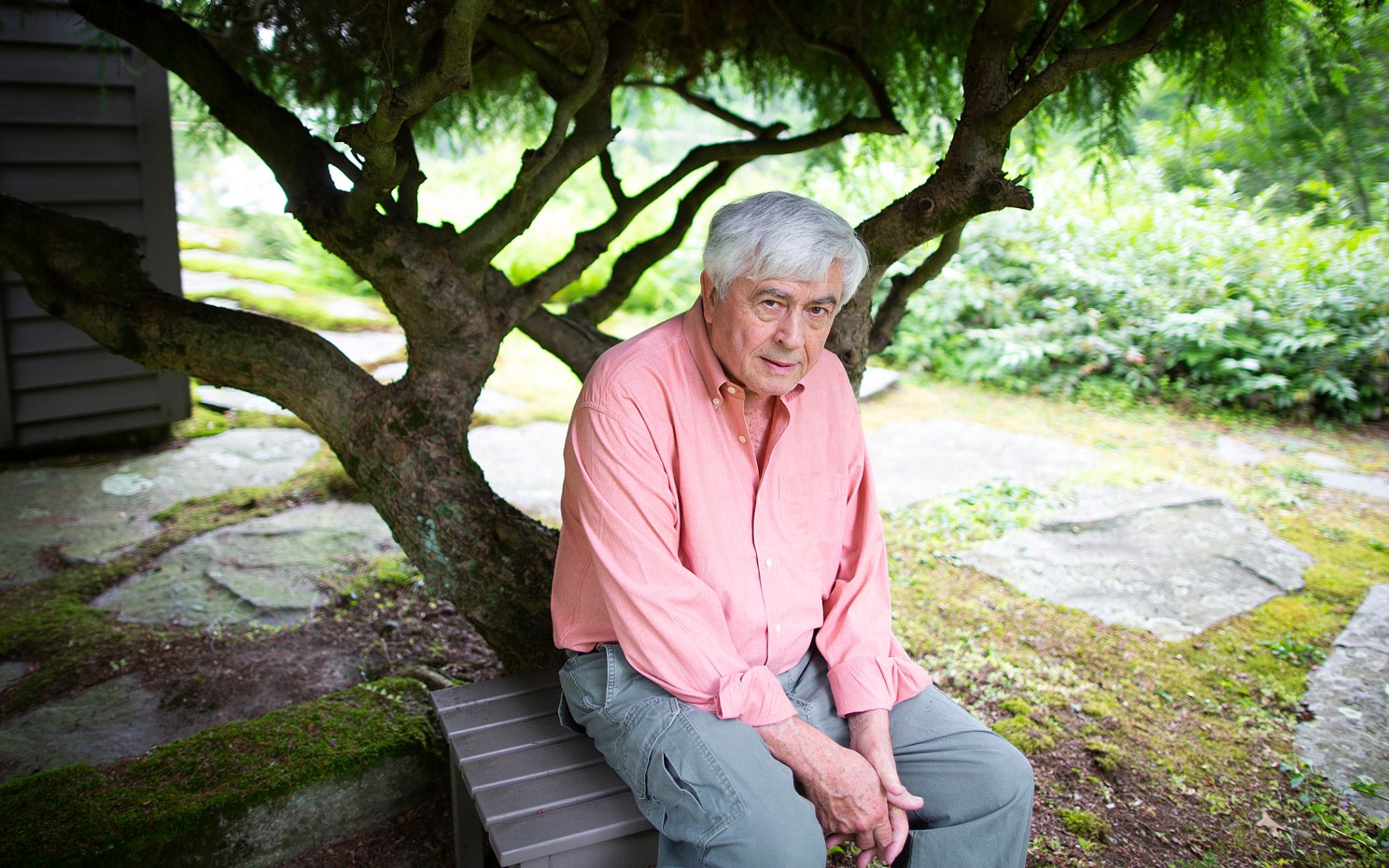

Tim Murphy in 2010 during 127th playing of “The Game” vs. Yale. Harvard came from behind to win, 28-21.

Harvard file photo

How did you approach being the head guy at Maine?

So, I didn’t think I had all the answers, but I went in knowing I was going to act presidential. I knew there was a certain degree of how you project yourself that is critical to being a leader. I was going to lead by example by being a hard worker. I was going to lead by being demanding but in a positive way. That doesn’t always come natural when all of a sudden you’re the head guy, but as you have some success then it becomes a very natural part of you.

After coaching at Maine for two years, you ended up as head coach at the University of Cincinnati, which was struggling at the time. Why’d you take that job?

Very simple. No one wanted it, and the program had hit bottom. Let me explain. Rick Taylor, whom I worked with at BU, went from being the director of athletics at Boston University to the director of athletics at Cincinnati. He had faith that I was the guy to turn things around. He was very honest with me. He said, “Listen, you weren’t the first guy on the list, but no one will take the job.” I asked why, and he explains how they’re ranked the 122nd in the country out of 123, and, by the way, they’re going to be hit with a three-year NCAA penalty and lose 15 more scholarships. Anyway, I don’t think I got the job because someone considered me a genius. I took the job because I had a boss who believed in me. The program was way down so there was only one way to go. Up.

It did go up. You also got married around this time, right?

My wife, Martha, and I were dating when I was at Maine for a couple of years. When I got the job as the head coach of Cincinnati and we were talking about moving, she basically said she’s not going without a ring. She recruited me, in a way. So, we became engaged, and we got married the summer before the first season.

No honeymoon then?

We got married in July and headed right into our first Division I season. We agreed to put it off to the next summer, but it didn’t happen then either.

You stayed at Cincinnati for five years. That last year, you had just come off the first winning season there in 11 years and Harvard came knocking. You often say you had some concerns about taking the job. What changed your mind?

I was extraordinarily fortunate to be the youngest major college head coach in the country at the time, but I was interested in the Harvard job because I coached two years at an Ivy League school and had been so impressed by the character of the kids. That meant a lot because I had gone from a kid who thought he was probably going to go to the Marine Corps to someone who really valued education and loved that environment of having true student-athletes.

When I went into the interview, I really thought I wasn’t going to take the job because they had just offered me a new contract at Cincinnati. The primary people who conducted the interviews throughout the full day I was here were dean of admissions Bill Fitzsimmons; the alumni director, Jack Reardon; and the athletic director, Bill Cleary. What finalized my decision was that I had that same gut feeling I’ve had about how I choose coaches and how I choose student-athletes. The effect of their character was just almost palpable in terms of these are really good people. They are high-character people. I just knew that this is where I wanted to be.

What was the state of the Harvard program?

Harvard was struggling a bit. Harvard was fourth or fifth in winning percentage in the league since the Ivy League was created in 1964. They hadn’t had a winning season in years. There was definitely room for improvement.

The only way to go was up, again?

Exactly. The first year, we really struggled. The second year, we were better. The third year, too. The fourth year, which was our first recruiting class, we ended up with what was almost the first perfect season in School history — nine wins. One play away from being 10-0. We’ve been pretty consistent since.

“The wins, even the big ones, you don’t remember quite as vividly as the devastating losses.”

How have you kept that going?

Personnel, personnel, personnel, and adapting. If you stay the same in everything you do as things around you are changing, eventually you’re going to hit a wall. You just have to adapt and evolve and change. Recruits change; the College changes; schemes change; football changes. You have to try to be on top of that, and not only on top of them but hopefully ahead of the curve.

One of the lessons your players say really sticks with them is “Murphy Time.” It’s more than being on time; it’s actually always being five minutes early. Why is that a good habit to develop?

Murphy Time is a small piece. It’s just one of the beliefs I have. It’s a virtue to always be on time, and if you’re ahead of time, you’re never late, so you’re guaranteed to have that virtue. I think it’s a sign of highly motivated, high-character people. They’re going to be on time or ahead of time. It’s a very small thing, but it goes a long way.

Can you describe your coaching philosophy?

I’m a teacher, No. 1, but I’m also a manager. No. 2, the biggest things we want to teach our student-athletes are life lessons. Some of the basic life lessons may seem corny and trite, but they work. In preseason, we always talk about never giving up — never, ever giving up. As corny as that sounds, that’s the way life is. It’s going to be hard at times. We’re all going to have some real challenges in our life on many levels. Having the ability to just fight all the stuff that you’re going to face in life and have that resiliency is critical to success on many levels. That can be applied to real-life things other than just the sport of football.

So, it’s all about life lessons. It’s everything we do. Don’t settle for an average grade in the class when you can get an A. Be the best you can be. The question just is: What are we going to focus on to maximize ourselves?

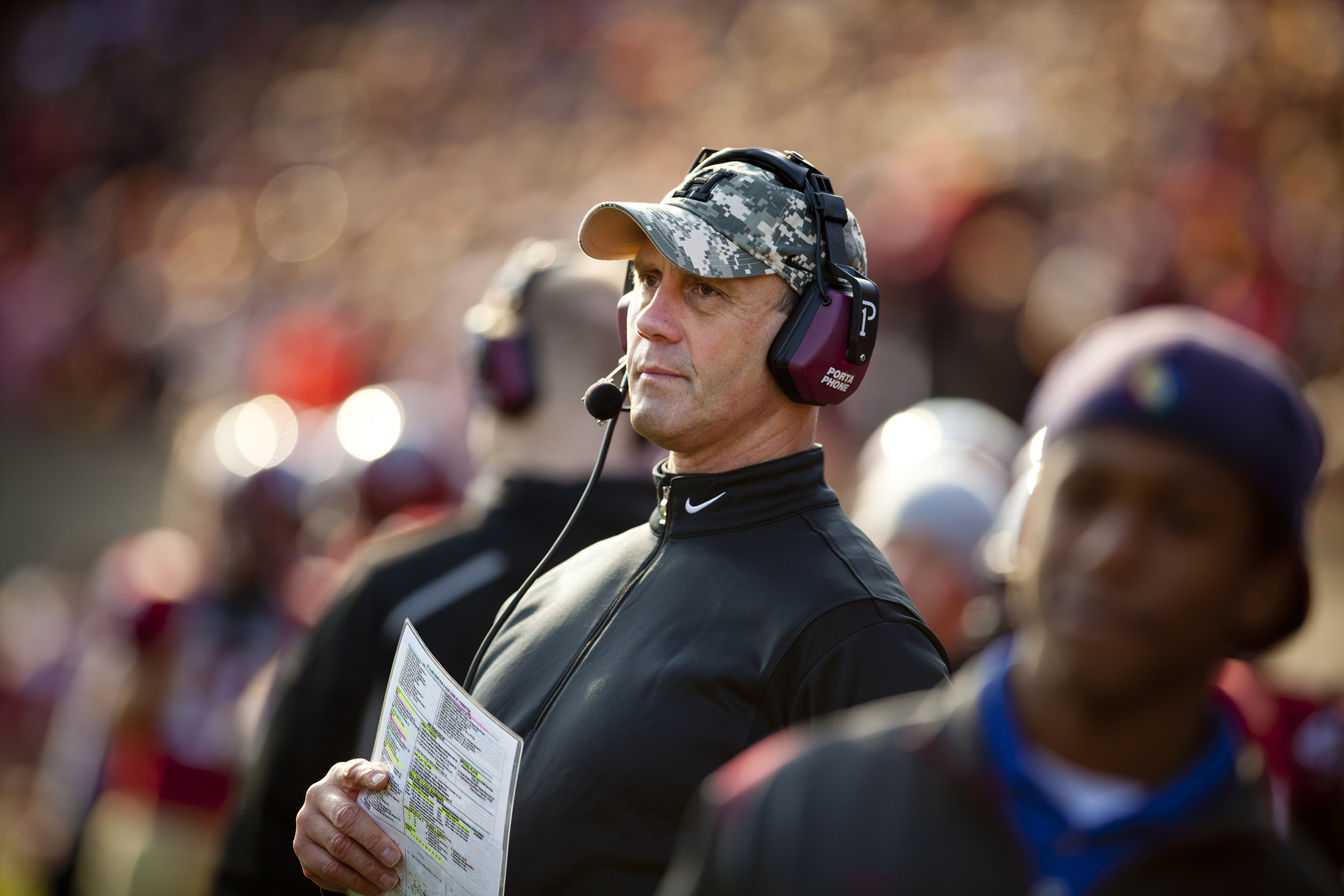

Harvard celebrates finishing the 2004 season undefeated with a win over rival Yale.

Harvard file photo

In recent years it seems there has been a greater emphasis placed on player safety, and we see a lot more news about studies being done, particularly regarding head trauma. Do you think football is safer now than it was before?

Player safety is certainly a top priority for our program, team, and the Ivy League. The way the NCAA has appropriately evolved is to change the rules regarding protecting defenseless players and severely limiting the amount of full contact you can have in practice. The result is that practice regimen, in a positive way, is vastly different and better than when I played high school and college football.

What have been some of the biggest wins and, on the flip side, the biggest defeats that have stuck with you?

The wins, even the big ones, you don’t remember quite as vividly as the devastating losses. We’ve been fortunate to have our share of wins, but the one that got away from us during that first Ivy League championship year stung because we lost our perfect season.

What happened?

We were up 21-0 against Bucknell. I got way too conservative in the second half, and we lost. It would have been the first perfect season in Harvard football history, meaning back to the Ivy League. That one haunts me. The Yale overtime that we lost in 2019 comes to mind, too. We had a significant fourth quarter lead. There was a game against Dartmouth we had locked up and lost on a Hail Mary. For whatever reason, those tend to be more memorable than the successes. When you succeed in life, in whatever endeavor, we have a tendency to embrace it quickly and move on. But you always remember the bad stuff.

What about the 2012 season’s 39-34 loss at Princeton? I read an interesting anecdote about you and your son, Conor, after that game.

Wow, I wouldn’t have remembered that. I’ll tell you exactly what you’re going to say. My son, Conor, who ended up being a good high school quarterback, came home just miserable from the Princeton loss. He wanted to play football with me. I said, “No, I don’t feel like it.” My wife just elbowed me and gave me a dirty look, and I gave in. Half-hour later, I had already moved on from that loss. It was just one of those great life lessons: We’re not curing cancer out there … but don’t tell that to a coach right after a game.

“In preseason, we always talk about never giving up — never, ever giving up. As corny as that sounds, that’s the way life is. It’s going to be hard at times.”

Do you get to relax during the off-season?

There is no off-season. That’s the reality of it. The minute the season ends you’re on the road pretty much nonstop through the recruiting process and flying back from somewhere in the far corners of the continental U.S. before going back on the road for weekend recruiting visits. It’s just the way recruiting has continued to evolve. It’s almost a 24/7 thing. I always say that you’ve got to adapt and evolve about every four to seven years, philosophies, strategies, and certainly that pertains to recruiting. This generation of kids is really into using and being on social media, and if you don’t embrace that and become good at it in the recruiting process, you will not succeed. The good news is that Zoom is a really good forum to be able to not have to get on a plane so early in the process. I did something like 300 or 400 Zoom meetings with potential recruits over the COVID period.

Have you given any thought to what you’ll do when you’re done with coaching?

Yes, but I haven’t figured it out yet. Two things, though: One, I won’t be able to stop working, so I will do something that doesn’t require every waking minute of my life. I’ve thought about maybe teaching a leadership course at a college and I’ve thought about the possibility of getting into some level of broadcasting. I also love to play sports. I love to play golf, but I don’t have any time to. I love to play tennis. I love to work out. I love to swim. I just don’t have time to do all those things, so the ability to have more time to play is very attractive. The ability to have more time for my family is very attractive. The ability to do something a little slower-paced — those things are attractive. I know I’m not going to be — I can’t be — that guy who just does nothing.

Last question: Did you and your wife ever finally take the honeymoon you postponed two years as the Cincinnati head coach?

Here’s where it gets interesting. Two years ago, my wife said, “That’s it. I’m putting my foot down. We’re going on a honeymoon. We’re going to Paris.” I said, “Whatever you want.” She had it all booked. You can’t make this up. Two or three days before our flights were set to go to Paris, France canceled all incoming flights. Now you know, the timing.

COVID.

Yes. So maybe I’ll finally have time for a honeymoon, too.