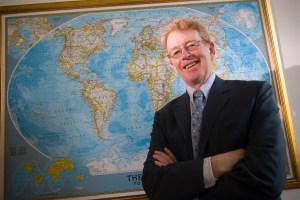

For Faust, new year brings fresh challenges

Harvard President Drew Faust on single-gender social organizations, endowment issues, the importance of increasing diversity and safeguarding the humanities, and how she spends her downtime.

In Q&A, Harvard president muses on single-gender groups, endowment concerns, the centrality of diversity and the humanities, and how she spends her downtime

As Harvard University enters another academic year, President Drew Faust sat down with the Gazette to discuss her priorities for the months ahead. The wide-ranging conversation touched on topics including The Harvard Campaign, the University’s stance on single-gender social organizations, the vision for the Allston campus, the importance of the humanities in a liberal arts education, and the newest member of Faust’s family — an adopted shelter puppy named Alice.

GAZETTE: Could you outline what you see as Harvard’s priorities for the year ahead?

FAUST: There is a lot going on at Harvard, including, of course, the continuation of The Harvard Campaign. We still have important parts of the campaign that we want to address and goals we want to fulfill. Some of those are individual School goals, while others are thematic areas that we want to make sure we attend to. Financial aid is one of those, as is House renewal in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

I’m very hopeful that we’ll be able to raise significant dollars for science funding in the next year and three-quarters that are in place before the end of the campaign. There’s the Harvard Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences building in Allston, which we need to raise money to support, and that’s a very important part of what we want to do. I have some goals in the arts, including raising money to endow the new Theater, Dance & Media concentration. So there are a variety of specific projects that we hope to fund and that will be an important part of this year.

“I’m very focused on the issues that students have raised in recent years so eloquently about inclusion and belonging.”

I spoke a moment ago about Allston. That is another priority for the year ahead — making progress on the Science and Engineering Complex and continuing to enhance the intersections and relationships between Harvard Business School [HBS] and the Harvard Paulson School. They had a wonderful joint faculty symposium that helped to demonstrate the research uniting the intellectual strengths of both Schools, so I think we’re going to see more of that in the years to come.

The kinds of partnerships that we hope to be able to fashion with organizations outside of Harvard that will locate themselves in the enterprise research zone will also spark our imaginations and give us different perspectives on the intellectual work we do and translate those efforts into a world that will give them a place in business and in communities and in everyday life. I also hope to have a vibrant presence of the arts there, which I think will intersect nicely with the plans we’ve envisioned. So, that all excites me.

Other goals for the University as a whole: I’m very focused on the issues that students have raised in recent years so eloquently about inclusion and belonging. That will be something that the deans in their own Schools will be working hard on this year. But I too want to work on it on a University-wide basis and really address some of the concerns that we all have seen articulated.

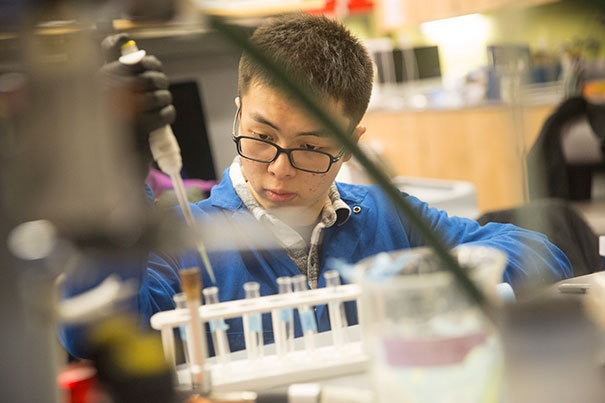

The life sciences will be an important area of focus. We have two new deans in Longwood, Michelle Williams at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health and George Daley at the Medical School, who will bring new energy to these efforts. And that’ll relate very closely to how we can both integrate life sciences better across the University and also strengthen life sciences in each of the three Schools in which they occur. So those are all important goals for the year.

GAZETTE: These are challenging times for American colleges and universities across the country, with many anticipating declines in their endowment returns. How would Harvard respond to a slide in the endowment?

FAUST: We have a formula on which we base the amount paid out of the endowment each year. So we calculate that formula with the variable of what the endowment performance in the preceding year has been. And then, based on that, we determine distribution. If we distribute either less or the same or just a bit more than what has been distributed, then that puts a lot of pressure on Schools and other entities in the central administration to figure out how to contain costs and how to make choices about what we will spend money on and what we won’t.

If endowment spending is to be constrained as a result of our endowment returns, that’s something everyone is going to have to consider, and make decisions that prioritize what’s most important to advance the academic mission of the institution. Those are conversations that will occur as we look at how those endowment returns come in, depending on what they turn out to be.

At a time when endowment returns look like they will be constrained maybe for some time to come, people across higher education are very concerned — not just at Harvard but more generally — about how we respond. This will be especially worthy of consideration in light of our involvement in what has been a very successful capital campaign.

“At a time when endowment returns look like they will be constrained maybe for some time to come, people across higher education are very concerned — not just at Harvard but more generally — about how we respond.”

We have the benefit of significant contributions for new activities and for spend-down money in some cases. In other cases, investments in the endowment raised as a result of the campaign will enable us to do some new things and support projects or efforts that the returns on our existing endowment portfolio might not be able to finance. The campaign is not a substitute for good endowment performance. But it can, in some ways, help us counter some of the constraints that might otherwise limit our ability to dream new dreams and introduce new initiatives.

GAZETTE: Stephen Blyth, the head of Harvard Management Company [HMC] that manages the endowment, recently stepped down, and Harvard’s endowment performance has trailed that of its peers in recent years. Do you have any concerns about the ongoing stewardship of the endowment?

FAUST: We have a very strong interim team in place, and I’m grateful for the leadership they have shown at a time of transition. There is a search underway, and there is a really excellent group of colleagues from the board of the Harvard Management Company with tremendous expertise, who are going to be advising on the search. We have a number of outstanding potential candidates, so I’m very optimistic that we’ll be able to appoint a new leader who will bring excellent judgment and experience to HMC.

GAZETTE: Any sense of the timing for that?

FAUST: We’d like to get the search done promptly. But I never put timelines on searches because you never can tell what’s going to happen. You may zero in on a candidate, think you’re all done, and then the candidate says, “Oh, I changed my mind,” or “I want to keep talking to you about this.” So searches, I would say, are as long as a piece of string.

GAZETTE: Last year Harvard announced a decision about the future of final clubs, sororities, and fraternities at the University. Could you briefly recap that?

FAUST: We have thought long and hard about this. And the provision that we have decided upon is one that says if you choose to be a member of a final club, you have the perfect right to do that. It is a choice you may make. But it also comes with certain outcomes, because we believe that these clubs are a negative force within the social environment of Harvard, and that, if you choose to be a member of one, you may not hold a leadership position in the College — which means of athletic teams or of certain significant organizations in the College. And you will not be recommended for prestigious fellowships by the dean of the College. That was the policy that was set forth.

There will be a group working with Dean [Rakesh] Khurana this year to figure out exactly how to implement the new policy — which groups are involved, how we determine those groups — and to work out the important details to make this a reality.

The real logic of this has been propelled by our commitment to Harvard as an inclusive community, in which the influence of exclusive organizations over student life is at odds with the fundamental values that we embrace as essential to the College experience. Final clubs began as all-male organizations. And although they were asked to go coed at a time when women from Radcliffe were really being fully integrated into the Harvard community, they declined to do so, and at that point they were forced by the dean to become independent organizations.

What happened was not that they withered away, which was I think what people anticipated, but rather — especially with the raise in the drinking age — became a real focus for social life in the College and have in many ways strengthened their influence among undergraduates in ways that we feel are at odds with what we would like to be, a community in which everyone can fully participate in the opportunities offered.

“Having conversations in this community about where we’ve come from and where we want to go will be really important.”

GAZETTE: How do you respond to the critics who complain that this decision limits a student’s ability to freely associate?

FAUST: Students have a perfect right to belong to these clubs. We are not telling them they can’t do that. But we’re saying that there are certain privileges of representing Harvard that will be curtailed by those who choose to belong to clubs whose values are at odds with Harvard. The formally recognized teams or social organizations that are the subject of this policy are ones that we fund with Harvard resources and are intended to be inclusive of all members of our community. There’s no right to leadership. Leadership is earned. Similarly, there’s no right to a recommendation from a dean for a fellowship. That too is earned.

This policy goes into effect with the class that enters next fall, so students who come to Harvard for that class and future classes that are subject to these rules will be able to choose whether or not they want to go to Harvard with this regulation in place.

GAZETTE: There’s been some backlash from members of women’s clubs who feel that their clubs could vanish along with the “support systems, safe spaces, and alumnae networks” that the clubs enable. How do you respond to those concerns?

FAUST: We need to be sure that we provide women with networking opportunities, with the support they need. We need to figure out the ways to do this. The women’s clubs have grown up because we, as a community, have not done that adequately. And so I don’t think that being this kind of organization — one that was created because something was withheld from you — is the best way to address these women’s needs.

GAZETTE: Making Harvard students feel included and part of the community is an ongoing effort at Harvard and at similar college campuses across the country. Can you share with us the status of the efforts on that front?

FAUST: Last academic year, in response to a report from the College Working Group on Diversity and Inclusion, I initiated the process of setting up a University-wide task force on inclusion and belonging. That group has grown out of conversations across the campus and among the dean’s leadership group, with students, and others to address some of the ways in which the University writ broadly — all of us — can improve issues related to inclusion and belonging. We will announce more details in the coming weeks but it will address a wide range of diversities that we want to support and enable, and will draw membership from every element of the community, from students, staff, and faculty. The views of this group will be extremely important in helping us understand how we leverage a lot of the work that’s gone on in individual Schools on these issues with a University-wide umbrella that can really reinforce and go beyond their efforts.

I also established a committee to help me think beyond a plaque installed this spring on Wadsworth House in memory of four enslaved persons who worked there, about what we should do next in terms of acknowledging and memorializing Harvard’s history with slavery. We are going to have a conference in the spring at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study sponsored by the President’s Office that I think will be quite a remarkable event. There are terrific people coming to talk about slavery and universities. There’ll be some emphasis on Harvard, but we’ll also look more broadly.

Having conversations in this community about where we’ve come from and where we want to go will be really important. I’ve spoken about this at freshman convocation and morning prayers. I’m also eager to work with the Schools on diversifying the faculty, helping deans and faculty members identify, recruit, and continue to enhance the numbers of underrepresented groups on our faculty, so that’s another important part of this as well.

GAZETTE: You mentioned sustainability. I wanted to touch on climate change. De-carbonizing the energy systems in our communities in response to climate change still poses an enormous challenge. How is Harvard positioning itself to contribute sustainable solutions on the local, regional, and global stage?

FAUST: Well, I see this as happening in a couple of different ways. One is we want to be a living laboratory in how we operate as an organization that uses energy. We’re coming now to the end of the first set of commitments. It was a short-term commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2016. And here we are in 2016. So by the end of this calendar year, at the very beginning of next year, we’ll be announcing how we’ve done. But we’ll also be formulating new goals to figure out how we go beyond what we’ve accomplished already and to figure out what the next stage of our commitment to our own practice should be. That’s one area in which we’ve been very innovative and inventive in the ways that we’ve addressed energy use within our own community.

Secondly, we have an enormous presence of teaching and research in this area, the teaching part of it being creating the leaders of tomorrow who will carry forward in the war against climate change in a variety of fields, ranging from the Law School, where our faculty are working on models of legal intervention in this area, where there’s a student clinic that engages not just law students but students from public health and other parts of the University to show how they can all work together; at HBS, where faculty are exploring intersections with industry; at the Chan School of Public Health, where they’ve done so much on air pollution and health, including new evidence just this past year about the impact of climate on things like heart disease.

Faculty at the Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences are looking for solutions to storing renewable energy. A team has developed batteries that can store sun energy much longer, which is a critical breakthrough to make the movement from fossil-fuel dependence to other kinds of energy. At the Graduate School of Design, with the Green Buildings and Cities initiative, these are such important areas, and are only a few in which faculty are doing research. I think more and more people are alarmed about climate change, and so more and more faculty are involving themselves in these very important endeavors.

We funded something last year that I think is a model that we hope to replicate in other parts of the world, the Harvard Global Institute, which is an effort at the center of the University to address problems and intellectual issues that transcend both regions and fields. And the first initiative, funded by a generous donor from China, is a program led by someone in economics, Dale Jorgenson, and someone in the Engineering School, Mike McElroy, to collaborate with faculty and others in China on issues of climate in China. I’m hoping that we’ll get a gift that will enable us to have a parallel initiative in other geographies and to cross-fertilize one from the other. We’re thinking about how we can use our intellectual presence to enhance the ability of people all over the globe to make progress on this very, very significant problem.

“Who are we? Where are we going? Why should we go there? What is the purpose of life? How do I live a life of meaning and purpose? How do I understand other human beings? How are they like me and different from me?”

GAZETTE: Earlier this summer you took part in a conversation at the Aspen Ideas Festival with the American writer and critic Leon Wieseltier about the humanities. You mentioned that often the outcome of the humanities is not an answer but a question. In your mind, what questions do the humanities raise, and how do they help teach us?

FAUST: Who are we? Where are we going? Why should we go there? What is the purpose of life? How do I live a life of meaning and purpose? How do I understand other human beings? How are they like me and different from me? How do I understand different stages of life and the changes that make me different from a person I once was and will make me able to be different yet again? So I think they concern the essence of your own approach to being human but also an ability to look through the eyes of others at how they construe the world, so that you’re able to reach them, to touch them, to connect with them.

GAZETTE: In that same conversation, you said one of the things you hear the most from professors is, “My students don’t have the sort of patience required for long, extensive reading.” How can the humanities at Harvard help teach students that type of patience?

FAUST: Well, I recently spoke to the arriving class of graduate students at GSAS [the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences]. And I spoke to them about how, in a University where other students entering today know that they’re going to take two years to get an M.B.A. or four years to graduate from College or three years to get a law degree, they don’t know how long it’s going to take them to do a Ph.D. And so they need a kind of immersive attention, a kind of persistence and a willingness to follow questions wherever they lead, which I see as characteristic of that type of scholarship. And then I quoted from a wonderful, wonderful piece by Jennifer Roberts, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities, about patience and how in one of her classes she has her students sit in front of a work of art for three hours. At first, they can’t imagine doing such a thing. And then they see how much more they understand and find in an artifact after that length of time. So, as she puts it, being given permission to spend time in that way is an important part of her class and of learning to see in new ways.

The same, I would say, is true of reading: Not everything comes in 140 characters. And for many students, lengthy pieces of reading are alien, unwelcome. And yet, what is more delicious than falling into a book? And also the complexities that are possible to address in 140 pages or 140 books that you’re not going to get in 140 characters are an important part of learning, knowledge, understanding, of ambition. Also, to want to have that kind of depth is significant, too. There’s a general introductory course in humanities taught by some of our star faculty that endeavors to introduce students to this way of thinking and reading and give them a pathway out of a world that is always looking at how short can something be, how quickly can it be done, how fast can it be over with?

“The very public nature of everything we do is a circumstance that I had to learn to live with.”

GAZETTE: You are entering your 10th year as president. Is there anything that has surprised you about the job?

FAUST: When I took the job I knew that the president of Harvard was somebody who was scrutinized and a very public figure, but I don’t think I knew what that meant exactly, in two ways. One, Harvard is the symbol of higher education. Often, it’s a headline that the media wants to put on an article. It’s the example that gets used if some issue of higher education is being discussed. It sometimes, not infrequently, is the target if someone wants to criticize higher education. So the very public nature of everything we do is a circumstance that I had to learn to live with.

But, two, it also means that we have the opportunity to use that platform for good, that when we take a stand or take a leadership action, we can really have an impact on the broader higher education community and on the world. So the ability to move an agenda is one that is also granted by this visibility. When we introduced our financial aid program back in the fall of 2007, other universities followed suit, and we had a transformative impact on the cost of higher education for lower- and middle-income students. And that opportunity is one that comes along with all the scrutiny. I think I didn’t realize the full dimensions of either aspect of that, both the possibilities and the challenges of that visibility.

GAZETTE: Can you talk a little bit about what’s it like to live at Elmwood, the historic house that was once the home of the poet James Russell Lowell?

FAUST: One aspect of it is it’s a very human-scale house. A lot of presidential houses are like bank lobbies, or they have huge public spaces that don’t seem welcoming at all. I think every room in Elmwood is of a scale that is welcoming. You could have two people in that room and have it seem an appropriate use of the room. So that makes me feel very much at home in that house, and it’s very relaxing to not feel that you are in a bank lobby. It also has challenges when you are trying to entertain because you don’t have a bank lobby in which to fit everybody.

I think it also has “good ghosts.” There aren’t doors banging or anything, but I sit there and think, “I am sitting in this room, and probably every important intellectual of 19th-century America was here. Henry James would come visit James Russell Lowell, who was the occupant of the house. I am sure Thoreau was there, I am sure Emerson was there, I am sure Longfellow was there.” I just hope that maybe a little of this will seep into my head when I am writing or thinking. It’s good company.

Ambrose Bierce is a writer who just was wonderfully acerbic and ironic — he was wounded four times in the Civil War — but he once wrote something that he titled “Alone in Bad Company,” so [the reverse of] that is sort of like when you are alone at Elmwood. You are in good company because all of these extraordinary people have been in that house.

GAZETTE: How did you spend your summer, and how do you relax?

FAUST: I think I relax by reading, by going to Cape Cod. I guess the big event of my summer was I got a new puppy.

GAZETTE: What kind?

FAUST: She came from a shelter, so I am not sure of her origins. When we got her she was 4 months old. She is now 6 months old. Her name is Alice. She’s delightful. Exuberant is the right word … she is some kind of hunter. She points. I think she might be some kind of herder because she also herds. You know how they get down and look, she does that. So I want to get a dog DNA test and try to figure out what she is. I spent a lot of time this summer working with her.

GAZETTE: Did you have a top book on your reading list this summer?

FAUST: I am reading a book called “Nothing Ever Dies” by Viet Thanh Nguyen. It’s a book about memory and Vietnam by the man who won the Pulitzer Prize in the spring for fiction for a book called “The Sympathizer.” This is a nonfiction book about history and memory. He was a Radcliffe Fellow a couple of years ago.

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about race and history, but Vietnam interests me a lot because I grew up as a college student with the Vietnam War, and I am planning to go to Vietnam as part of a Harvard trip this spring. So this book has kind of come at an intersection of a number of interests.

GAZETTE: Did you ever read “Dispatches” [by Michael Herr]?

FAUST: Oh, that is the best book. I think that is the best American book about the war.

GAZETTE: Did you watch much of the Olympics? Did you have a favorite Olympic moment?

FAUST: I watched some. Maybe Usain Bolt — he was amazing. Superhuman, isn’t he? He just looks like he is an entirely other embodiment of humanity from the people he runs against.