Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff

‘I wanted to warn future social movements that listening only to one’s own side can generate dangerous amounts of unrealism’

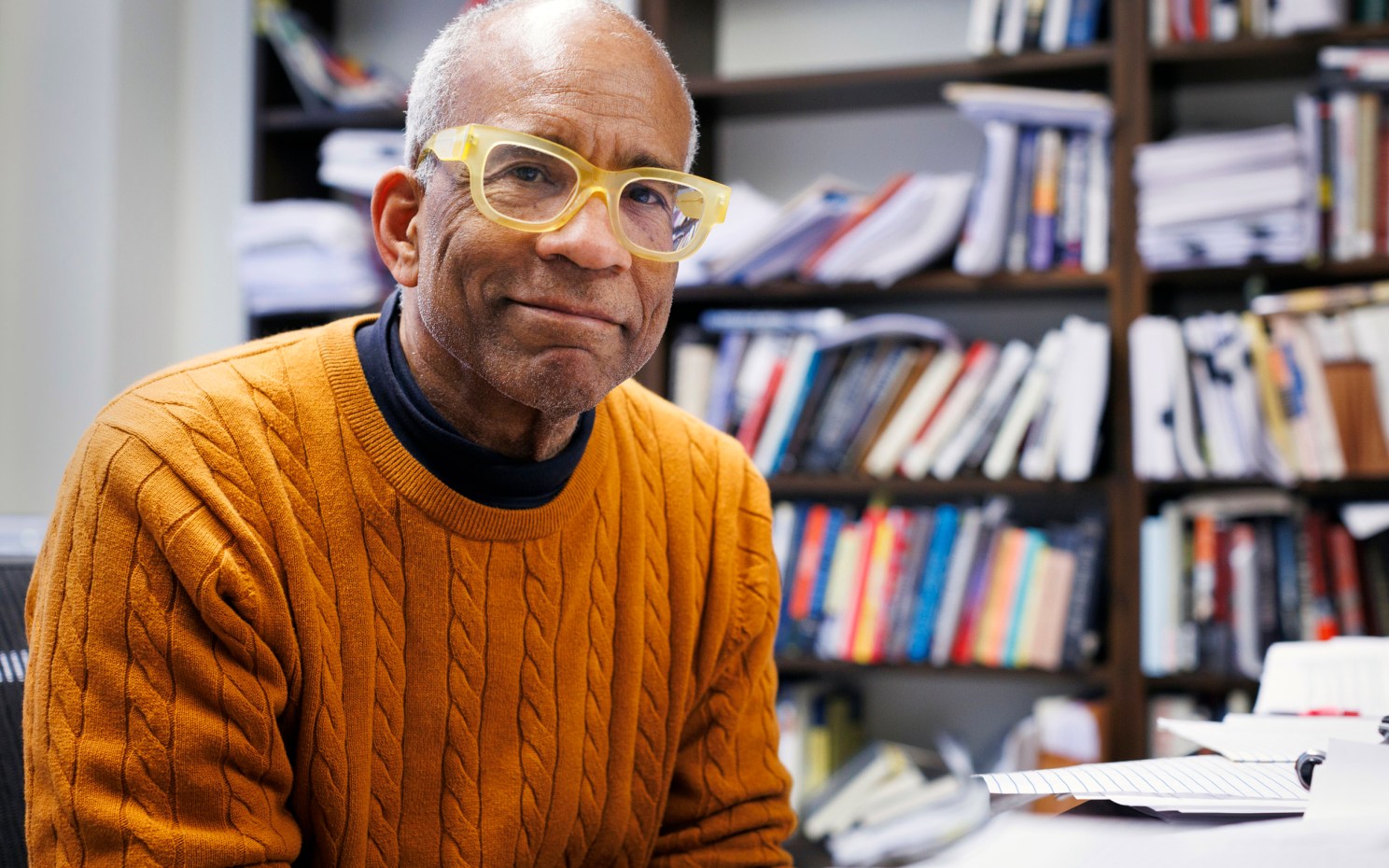

Jane Mansbridge talks about her ‘jagged trajectory’ to becoming one of the world’s leading scholars of democratic theory

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

Jane Mansbridge, Ph.D. ’71, a political scientist and one of the world’s most prominent scholars of democratic theory, came to the field that “helps citizens better govern themselves” almost by accident. Born in New York City and raised in Weston, Conn., she graduated from Wellesley College in 1961, and following a bumpy experience as a graduate student in Harvard’s History Department, turned to government. Cambridge then was awash in protests over women’s rights, Civil Rights, and the war in Vietnam, and Mansbridge became involved in the folk music scene, co-ops, various collectives, and women’s organizations. After receiving her doctorate she taught at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University before returning to Harvard as a faculty member in 1996. In 2018, she was awarded the Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science, known as the Nobel Prize in the field, for “having shaped our understanding of democracy in its direct and representative forms, with incisiveness, deep commitment and feminist theory.” Mansbridge is the Adams Professor of Political Leadership and Democratic Values at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, where she is a popular and highly respected teacher.

Where did you grow up? As you were growing up, what world event made a big impact on you?

I grew up in a small town in Connecticut that is now home to many rich people, but when I was growing up it was decidedly mixed-class. My graduating class from middle school had just 25 kids, only one of whom was from a professional-class family, although three or four more were from upper-middle-class families. Several of my classmates were from a neighboring town that in that era was a poor factory town, and they had bad teeth and poor health. One had needed crutches all her life. One was illiterate until sixth grade.

My high school was bigger, but I was bullied in high school for being bookish and a smart girl. That left me with a vivid realization that not everyone liked the kind of person I was or the values I had. The experience may have contributed to my later drive to find out more about people who were not like me.

World events were not as important to my life as the people in my life. My father had a great impact on me. He had left England, a country he loved, because he hated its class system. He passed on to his children his love for American egalitarian ideals — not that we live in an equal country by any manner of means, although we were closer to a more equal country at the time when I was growing up.

What books did you enjoy reading growing up?

I just loved everything. I read every book on horses in the school library. I lived in the country, and I didn’t have any friends nearby, and I read lots and lots of things in my parents’ bookcases, most of which were above my comprehension. I remember I brought a magazine from school that had some sexy stuff in it. My mother was very disapproving, and she said, “Well, if you want to read things about sex, you should read James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’” I did, but I couldn’t make head nor tail of it. I kept asking, “Where’s the sexy part?” [Laughs.]

Can you talk more about your parents, and your experience of being bullied in school?

My mother was a full-time mother, and my father started Cambridge University Press in the United States. They were both enthusiasts; my mother loved traveling, and my father loved books. They both conveyed to me that in the best world, you can get tremendous excitement from your work, that you can love what you do. Not that I thought I could get such work. I didn’t have any professional goals, but I did pick up the possibilities.

“Life is an exploration. … That’s what I want to get across to young people; you may run into tremendous obstacles. … Those things can happen, and you still can succeed.”

As for being bullied in school, it all happened because I was chosen by a group of Westport artists who were asked to pick a “homecoming queen” at a high school dance. I guess I looked like the quintessential American girl. They put a crown on my head, and the band played. It was all wonderful. Until the next day, when I walked down the hall, and they called me “Queenie,” and I became an object of derision. That continued even after I went away to a school in Switzerland for six months in my junior year of high school. My parents didn’t have a lot of money, but they scraped together the money to send me away to school for that short period. They didn’t let on they knew I was being bullied, but I think that was the reason why they did it. I’m sure I didn’t say anything to my parents about what was happening to me. When I came back, I realized I hadn’t escaped it by going away, because the bullying continued. My desire was really just not to be noticed. Then I went to college and never again did I feel that weight of otherness. But it left me with a weariness and an appreciation of the power of people who don’t think you’re one of them.

But I don’t want to downplay the positive experiences of my childhood. I went to church every Sunday. I was in the choir. When we went away on vacation, we would go to new churches and bellow out the hymns. My dad was much taller than me, and I would sing standing next to him. I only let myself sing loud when he was singing because his voice was much louder than mine, and it drowned me out. That way, I got both wonderful things: I got to sing loud, but also nobody could hear me … I loved growing up in a small town.

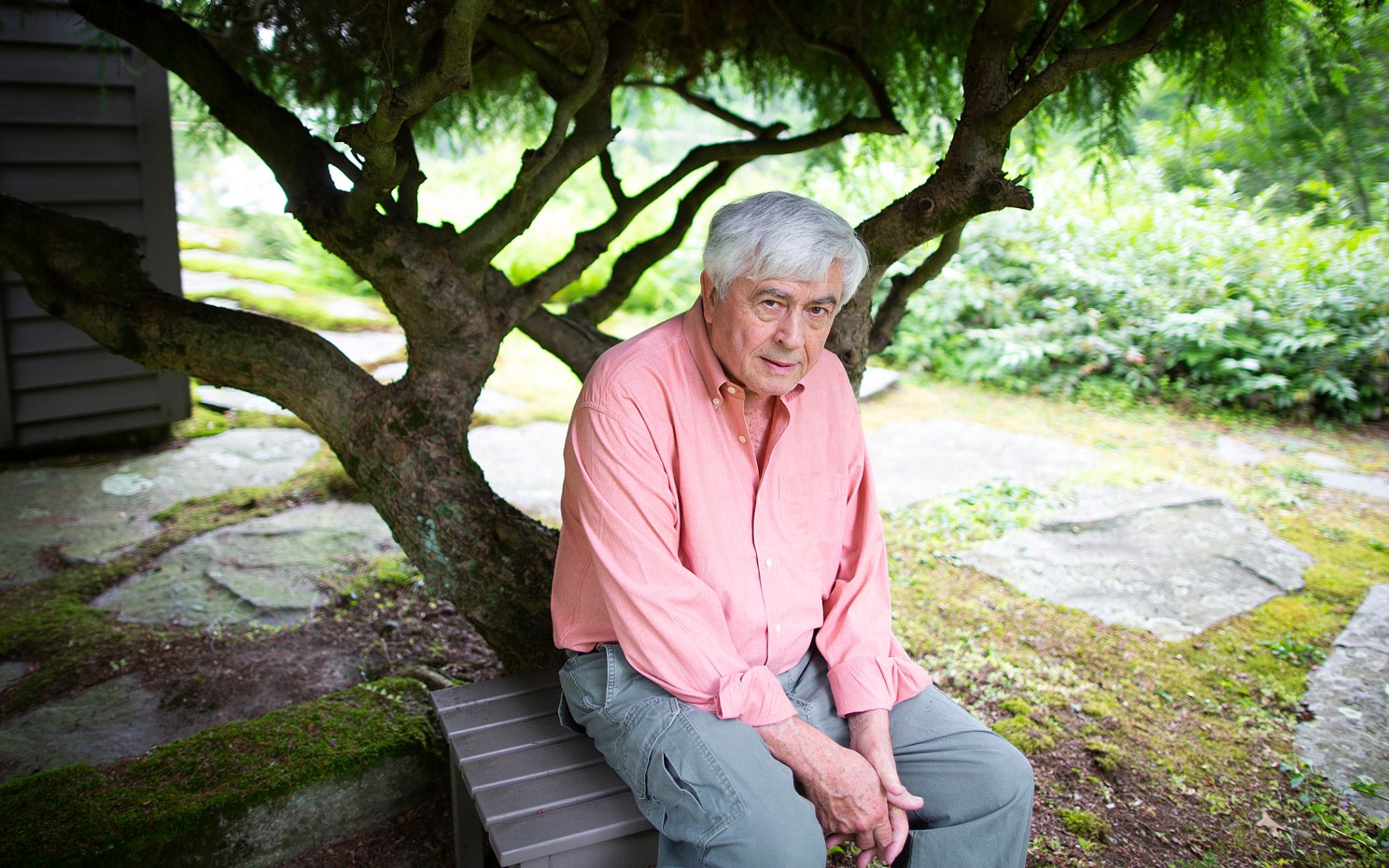

Mansbridge in Wellfleet, when she was laying the groundwork for what was to become her influential book “Beyond Adversary Democracy.” Mansbridge and her newborn son Nathaniel Mansbridge Jencks (1978).

Photos courtesy of Jane Mansbridge

You went to Wellesley College for undergraduate studies? Why Wellesley?

I had a taste of an all-women’s school when I went away to that boarding school in Switzerland. There, I suddenly experienced what it was like not to have the social pressure of boys all the time and to be able just to read and live each day as it came along. At Wellesley I loved keeping boys to the weekend and diving into the classes, the books, and my friends during the week. Several years ago, I was invited to give a class at Wellesley, and when I walked into the building in which I was to teach, I was almost knocked off my feet. All the portraits on the walls were of women. It felt so welcoming, so unfraught, and it reminded me of how much at home I had felt there.

At Wellesley, I felt free to be who I was. I had lots of friends, and a small group of good friends.

Wellesley was a place where I could just lose myself in my books. I never got more than a B-plus on an exam because I never studied for exams. I didn’t feel I had to study. I just felt I could let myself loose. It was really great. It was lots and lots of fun.

Mansbridge, when she was active in the Boston women’s movement, watching a taekwondo demonstration in the Boston Public Garden (circa 1970).

Photo courtesy of Jane Mansbridge

And then you came to Harvard to do graduate studies.

I went to Wellesley in 1957, before the second wave of the women’s movement. Unusually, among my four closest friends, three were planning professional careers — as a physicist, a doctor, and a philosopher. But I was expecting to get married and have children, as were most of my classmates. As I approached graduation, I realized I needed to do something to earn a living, and at that time, women became nurses, secretaries, or teachers. At the urging of my future husband, Owen de Long, I applied to the Harvard History Department. He planned to go on to grad school at Harvard in the Government Department. That is the reason why I went to graduate school. I did not take myself particularly seriously as a professional. I did reasonably well in my courses, but I was doing what Arlie Hochschild called the “second shift,” doing the grocery shopping, cooking meals, etc. Through my husband, I became involved in the folk music scene in Cambridge, and that, not graduate school, became the source of most of my friends. The upshot was that I flunked my graduate school general exams so badly they told me they had considered not letting me take them again. I learned later that the History Department intentionally admitted a third more people than they intended to let through and used the general exams to weed them out. I also learned that the department had a significant reputation for misogyny. Even though I was a feminist, I hadn’t considered that as part of the explanation for my experience! I decided I did not want to continue in the History Department. I bounced around a bit and eventually ended up as a student in the Government Department. Then I got divorced and, in the emotional whirlpool and depression afterwards, I had to drop my first dissertation topic, which would have required my doing work in France. I didn’t think I could handle being away from the support system of my friends.

In one interview, you said your career had many false starts. Was that one of those false starts?

I don’t want to call them false starts. It was a jagged trajectory. Life is an exploration. False starts sound as if there is a preordained path. If a step was a start that met an obstacle, it was still a start. That’s what I want to get across to young people; you may run into tremendous obstacles; you may be told you’re not wanted in the department; and you have to start all over again; and you may find something else that is actually more important to you. Those things can happen, and you still can succeed.

“Deliberation, in contrast to slogans, shouting, and Twitter outbursts, requires questioning others, listening hard to them, and then either finding some common ground or clarifying conflict.”

And when you began a career in political science, how did you develop a passion for the field?

When I started in the Government Department, I didn’t have a passion for government. I was driven by my desire to stay in academia and a more general passion for learning. While I was working on my dissertation (a nice little study of two Supreme Court justices, from which I have never published a word), I got involved in the women’s liberation movement and some of the participatory democracy collectives that were all around Cambridge: food co-ops, bicycle co-ops, preschool co-ops, etc. I became concerned that almost every participatory collective I was part of and that my friends were part of was having trouble. Many of them simply fell apart under the strain, often, of not sufficiently meeting their members’ demands for equality. I was inspired by the Cambridge collectives because they were filled with people I knew and loved, and I wanted to help them from falling apart. I thought, “Surely, political science can help with these problems.” I spent a couple of years investigating two in-depth case studies — a New England town meeting and a 41-person participatory workplace — and after that, gradually, inductively, began to make sense of what was going on. I realized that even in the most successful collectives, you’re going to find strong inequalities of power. But I also found out that among people with common interests, they don’t need equal power to protect their interests because the person with more power will protect the others’ interests. That turned out to be my contribution, which was eventually a normative theoretical contribution. I didn’t think of myself as a political theorist, but the biggest lesson of the work I did came in political theory. That’s how I ended up in what has been my life’s work.

In one of your most influential works, “Beyond Adversary Democracy” (1980), you compared two ideals of democracy: “adversary democracy” and “unitary democracy.” Could you explain the importance of both ideals of democracy?

Much of political science in the 1960s assumed that politics was about power and conflicting interests. As I studied the instances in which my town meeting and my participatory workplace were most successful, I realized that the members had a fair number of relatively common interests. It took me almost half a decade to realize it, but I eventually saw that some of the problems in the workplace came from approaching common interests with a model of democracy based on the assumption of conflict, or what I called “adversary democracy,” as opposed to the model I called “unitary democracy” based on more common interests. I argued that all democracies need to find ways to move fluidly between their moments of conflict and their moments of closer to common interests, not letting the conflict drive out the commonality. In the United States today conflict is tending to drive out commonality. We’re so caught up in conflict that it’s hard to see our common interests.

You’re known as an academic who combines academia with feminist and citizen activism. How did you become a feminist?

I became an activist because getting out of Vietnam was so important and, somewhat later, because making people understand that women should be equal was so important. Because I did not take myself seriously as a professional and because in those days Harvard allowed you to take a long time to finish your dissertation, I didn’t find much conflict between academia and activism.

I became a feminist because I went to Harvard for graduate school in the late 1960s. There were few female graduate students and no female professors in either the History or the Government departments. Women were not welcome. I wasn’t called on in class. If I didn’t take it upon myself to make an effort such as devising strategies to be called on, I would disappear. Women were not allowed in the Faculty Club, except with an escort. Women couldn’t use the library — they couldn’t be at Lamont — because “it might disturb the men.” That was the reason given to us. I didn’t pay much attention to it until the women’s movement came along and said, “This is wrong.” A lot of things in graduate school made me realize that the harmonious image of the world I grew up in, in which women would be the helpmate and the supporting cast to their husbands, who would make the money and protect the family, and the job of the woman would be to raise the children and produce a loving home, was not accurate for predicting the future.

You took part in the campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment, which ultimately failed to be ratified, and you wrote a book about it. Of the many lessons of this failure, which ones were the most painful for you?

The major lesson of my book, “Why We Lost the ERA,” was what I call now “the dynamic of deafness.” (I didn’t coin that term; Lani Guinier [Bennett Boskey Professor of Law, Emerita] gave it to me after she’d read the book.) The incentives for political activism and the stresses of the activist life lead the people who become activists to listen primarily to one another and not to the opposition. We, the activists, didn’t listen sufficiently to the opposition. I hoped in writing the book to get out there the idea that you have to fight the dynamics of your own social movement, you have to question and listen to other people. I wanted to warn future social movements that listening only to one’s own side can generate dangerous amounts of unrealism. I worry that parts of the left may be falling into this trap today.

“We desperately need knowledge of how to govern ourselves better. … Collectively, we human beings have to think ourselves out of this mess.”

You have also explored the need to promote political participation in democracy, and the need for Black people, women, and minorities to be represented by Black people, women, and minorities, and the need to hear alternative views. Why are these themes important for democracy?

More equal political participation, combined with more equal influence, which is not easy to come by, produces greater respect among citizens and better outcomes for the people on the bottom. Deliberation, in contrast to slogans, shouting, and Twitter outbursts, requires questioning others, listening hard to them, and then either finding some common ground or clarifying conflict. Democracy cannot succeed without both contest and deliberation. Blacks, women, and minorities particularly need to be represented by people with similar life experiences when the issues that come before their representatives are “uncrystallized,” meaning that those issues have not previously been processed through elections and campaigns. They also particularly need representatives from their own groups when there has been a history of communicative distrust between their group and the groups that most frequently rule.

You’re one of the world’s leading scholars in democracy. Is U.S. democracy under serious threat by rising inequality and populism?

U.S. democracy came about through a great deal of compromise, in which the Southerners got slaves counted as three-fifths of a person, and also got the Electoral College, which gave them more votes than their numerical proportion. American democracy may not necessarily be unique, but close to unique, in having this anti-democratic element built into its constitution.

Democracy in many countries of the world, not only the United States, is coming under serious threat. The complexities of modern interdependence produce increasing needs for regulation, which implicitly involves coercion. People don’t like coercion, so it’s increasingly important to legitimate the coercion that we must exercise. Yet just as our needs for legitimate governance are growing, the legitimacy we have is decreasing, precisely in part because we are necessarily experiencing more government coercion in our lives. Our citizenry is also becoming more educated and critical.

In addition, the number of years since World War II, when we last pulled together as a nation, are increasing. Specific circumstances in the U.S., such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, after which Southern conservatives gradually left the Democratic Party, have produced more homogenous parties and therefore greater polarization.

Before 1980 the Democratic Party was hegemonic in Congress, but it was also fractionated, so liberals and conservatives in that party reached out to liberals and conservatives in the Republican Party to get majorities to pass bills. Republicans, for their part, needed Democrats to facilitate their getting roads and harbors for their constituents. Each needed the other. After 1980, when the Democrats lost their powerful position and control of Congress was up for grabs, incentives changed. It became in the interest of members of each party to destroy the other. These are some of the reasons that government legitimacy is plummeting, just as we need more of it. This evolution poses threats to us all.

Many people don’t consider political science a science. What is your take on that?

At the root of “science” is knowledge. We desperately need knowledge of how to govern ourselves better when we face existential threats like global warming, which can be sufficiently mitigated only through collective action. Collectively, we human beings have to think ourselves out of this mess. Political scientists are the only group of people on earth who have the explicit mandate to help make us better at governing ourselves.

In 2018, you were awarded the Johan Skytte Prize primarily for your work, but you were also lauded for “having been a pioneering role model for women in political science.” Where did you find inspiration to become a role model for political scientists?

The members of the prize committee keep their deliberations completely secret so I had no intimations of their decision. But I was both delighted and gratified. My work began at the margins of the discipline — it did not follow any of the fashionable directions of the time. It has been wonderful to me that more and more people have over time found it helpful.

I’ve never much liked the idea of the role model because the term suggests that some people should model themselves on others — in this case, that people should model themselves on me — and I think that’s both impossible and potentially distorting. But I do think we can all look to others to adapt from them pieces of how we might ourselves act. That more pluralistic approach I can accept.

“Your work is so much better and your life is so much fuller if you can find something that’s really important to you to study. And if it’s important to the world, that’s even better.”

You’re a very respected teacher. What is the role teaching plays in your academic career? What have you learned from your students?

Teaching has played an important role in my career. I have particularly loved teaching at the Kennedy School, where I have students from all over the world. In my course on democratic theory, the whole point is to explore what’s so great, if anything, about democracy. I assign only original texts, from Aristotle to Foucault. Students write short reflections on the texts. I put the words of the text on the screen in class and have excerpts from the students’ reflections next to the relevant words of text, and then, as we analyze the text in class, I add my own comment on the laptop with a stylus so those words appear with the text on the screen as we discuss that text. What goes on in the classroom is a three-way interaction between the students, the text, and me. It can be explosive.

A good student is curious. A great student is curious and cares. I’ve learned from my students in many, many ways. I learned from one’s paper on the Arab Spring that few of the protest signs urged more democracy, and none drew on the sources in Islamic thought. Another student told me that when he went back to his hometown in Germany for Christmas and met his old high school friends at a bar, they complained about all the EU regulations. When he explained the reason for the regulations, they said (with rougher language than this), “Why didn’t anyone tell us?” That anecdote, among other things, led me to conceive the ideal of “recursive representation,” in which, throughout what I call the “representative system,” representatives in the legislative, administrative, and societal realms aim at more mutually responsive and iterated communication with their constituents.

You’ve been at your work for nearly 50 years. What keeps you going? How do you stay interested in your work?

Fear, now. It was hope when I started. Now I’m driven by extreme worry.

I think also at this age that I have some insights and background that may be useful. A team at the Kennedy School and I have developed a set of materials to help high-level congressional staff and members of Congress, as well as state legislators, negotiate better. The Library of Congress has adopted those materials to train congressional staff. That might help. The concept of “recursive representation” and institutions that further this ideal might help. A new project on “creative representation” is looking for the nodes of creativity in the representative system to see if such nodes can be identified, protected, and nurtured. All of this might help. That keeps me going.

What advice do you have for young scholars? What are you hopes for your students?

I would like them to know what I stumbled on later, which is that your work is so much better and your life is so much fuller if you can find something that’s really important to you to study. And if it’s important to the world, that’s even better. After you find a problem you’re interested in, you might look at it from all angles and try to understand it better than most people, and find a way in which you can contribute, and offer insights that can lead to a better understanding of the problem. I certainly didn’t think that way, about searching for an important problem, when I was younger. But I was lucky to have gone to graduate school in the 1960s, when so many people were asking, “How can we make things better?” I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. I hope my students may help in some way to make things better in the world.

The interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.