Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Integrating oral health and primary care can really help the health of this nation and of the world’

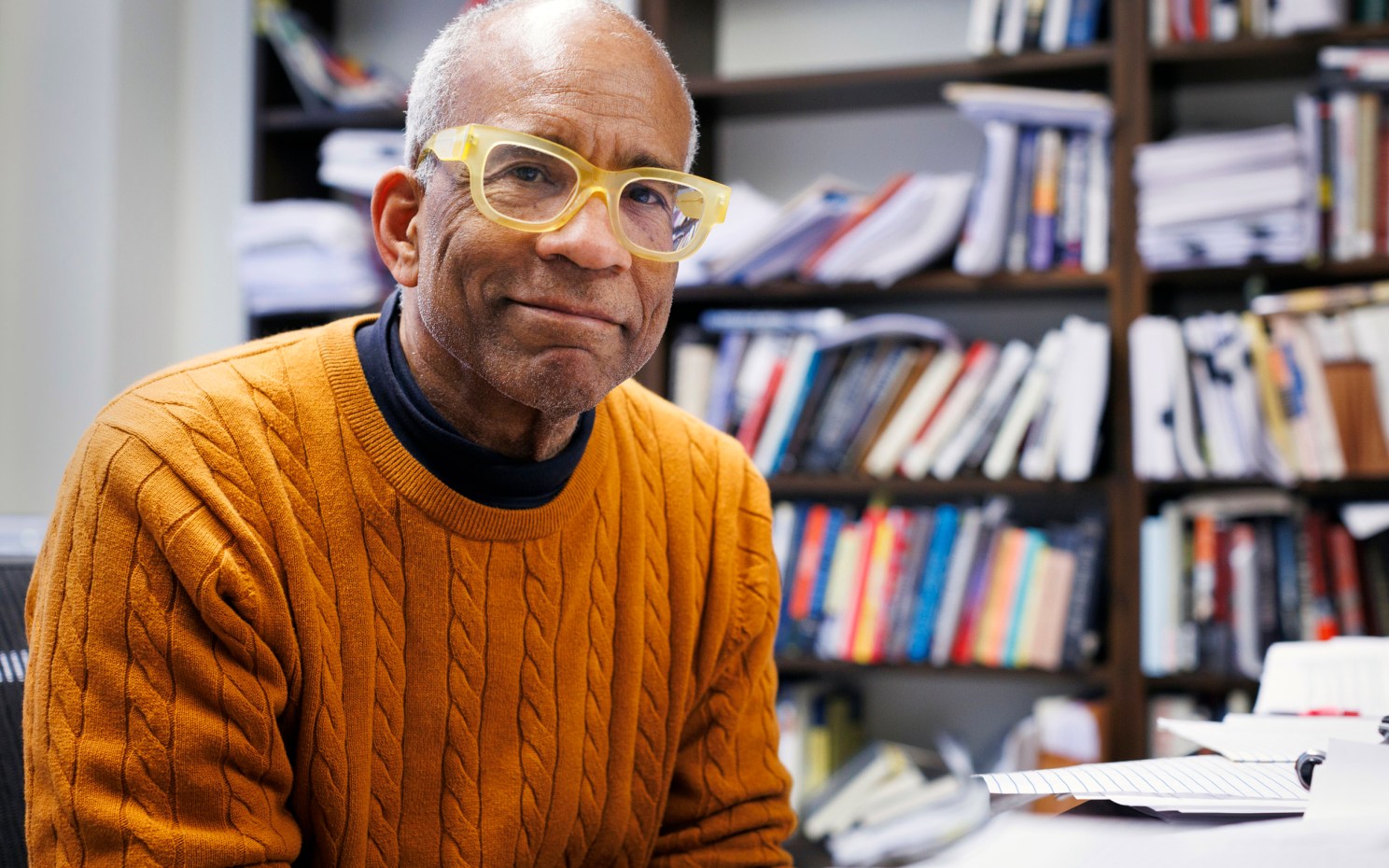

Bruce Donoff, University’s longest-serving current dean, details lessons learned as he prepares to hand off helm of School of Dental Medicine

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

The University’s longest-serving current dean, Harvard School of Dental Medicine’s Bruce Donoff, will step down in January after 28 years in the post and return to the School’s faculty. Donoff, the Walter C. Guralnick Distinguished Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, guided the School through various changes, championed reforms to dental education, and advocated a closer relationship between dentistry and primary medical care — he earned both his D.M.D. in 1967 and M.D. in 1973 at Harvard. Donoff, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who has conducted research on wound healing, bone grafts, oral cancer, and nerve repair, sat down with the Gazette recently to share his experiences in leadership and his hopes for dentistry’s future. A symposium and reception at the School will honor his service on Dec. 10.

Why don’t we start at the beginning. You grew up in New York?

I grew up in Brooklyn. I’m an only child. My mother was a schoolteacher, and my father was a manager at a printing company in Manhattan. He did not go to college, but he was very well-read. He could carry on a conversation with anybody. I grew up on the third floor of an apartment building and had my mother’s sister and two cousins, including my cousin Harvey — whom I went to school with — on the second floor. Brooklyn was a great place to grow up, because you interacted with all different kinds of people.

What were the neighborhoods like? Did they welcome each other or was there a “stay on your own side of the street” aspect?

They were welcoming. I lived at Troy and Lenox, and went to Erasmus Hall High School — Barbra Streisand and Bobby Fischer were in my homeroom for four years. But if I lived on the other side of Lenox Road, I would have gone to Wingate High School. And if I lived one block away, I would have gone to Tilden High School.

Barbra Streisand was in your homeroom?

She was.

How well did you know her?

I knew her to say hello. One time she was up here at the Kennedy School for something. I wanted to see her but had to go through about six secretaries to reach her.

How did dentistry come into the picture?

I was always interested in science. I went to Brooklyn College, where I paid $28.50 a semester for tuition and had a state scholarship every semester. Brooklyn College was a great experience. That’s where I met my wife. I lived at home and joined a fraternity, Alpha Epsilon Pi, which provided a social outlet. I was a chemistry major, although I loved history. I started doing research with one of my biochem professors on active sites of enzymes, and I was thrilled to do history term papers that took me to the main branch of the New York Public Library. I loved going to the main library, but the other reason for going is the last automat in New York was down the street. Do you know what an automat was.

I don’t.

Horn & Hardart automats were a kind of cafeteria where you put nickels into slots and you got your food out. It was a great concept, though it faded and never got resurrected.

What’s your wife’s name?

My wife’s name is Mady. She was a speech and theater major and did a lot of costume design. I used to tutor her in physics and chemistry, that’s how we met. She’s a great lady. We got married in December of my second year here in Dental School. I always joke she taught so she could keep me in the style to which I was accustomed. She wound up getting a job in Malden, and we lived right up here by Brigham Circle. She took two trains to get to Malden and made some good friends. She is an extraordinary person. She gives her time to everyone.

How important has your marriage been to your career and your life?

Fabulous. She’s a common-sense person and a great adviser and always supportive. And there were a few times when there were serious decisions to be made. Whether to go back to Medical School after Dental School was one. Taking this deanship was another. She was a guidance counselor in the Brookline schools for about 30 years, retired 10 years ago, served on more boards than humanly possible. And now is president of our temple, a big one — 1,360 families — including the president of our University.

How did you go from studying chemistry in college to coming up here for dental school?

That’s a great question. I was also considering medical school, but I wanted to combine teaching, research, and practice. I met the dean of students here at the Dental School, Howard Oaks, and he convinced me that I could do all of this easier through Harvard School of Dental Medicine. I believed him. He was a very persuasive fellow. We came up here — there were two of us from Brooklyn College who went to Dental School and three who went to the Medical School that year.

Tell me about your dental education. How different was it from what a student gets here now?

Well, the Harvard Dental School was the first dental school associated with a university and its medical school. In fact, the whole profession might be different if it had been the very first dental school — I’m very passionate about medical/dental integration. My education at that time was quite different, though philosophically the same. We took every single Medical School course. I took tropical medicine and even took medical boards at the end of my second year, before we came to the Dental School. Now, it’s 14 months together [with the medical students] and, of course, the learning pedagogy is different. But it was a great education. David Weisberger chaired oral surgery and oral medicine at Mass. General and was the chairman of the department here. Weisberger was a very talented teacher. His class was a highlight of Dental School for many. He’d ask one member of the class to go to a cabinet where he had stored all these lantern slides, and he say, “Pick a set.” These were slides of patients he’d seen — and they were unbelievable cases. We’d spend the next hour, hour and a half discussing the case. Amazing experience. In those days, drug companies could give you black bags — I still have my black bag in my closet — and there was a little red book, “How to Take a History and Do a Physical Exam.” I was assigned and went off to see my first patient at the Brigham. Now, there’s a lot of preparation. In 1986, I instituted — along with the Medical School — “Introduction to Medicine,” in which first-year students learn to take a history and do a physical exam. Now it’s entirely different.

“I was also considering medical school, but I wanted to combine teaching, research, and practice. I met the dean of students here at the Dental School, Howard Oaks, and he convinced me that I could do all of this easier through Harvard School of Dental Medicine.”

So, you took courses at the Medical School for your dental degree and later looped back to HMS for your M.D. Why?

When I was a senior, my wife and I discussed whether I should go get my M.D. before pursuing oral and maxillofacial surgery, but Harvard didn’t allow transfers anymore. The Medical School was very strict about closing any back doors in. But Walter Guralnick, the head of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, along with the Medical School and Gerry Austen at Mass. General Hospital, devised a program that would allow dental graduates from Harvard to return to the Medical School as part of the program at the MGH in oral and maxillofacial surgery. The reason for that is, with the M.D., you could do general surgery at a more appropriate level of experience. At that time, the specialty was expanding and you did just a three- or four-month rotation in general surgery. The M.D. program was at least one year, sometimes two. We had great success with that program and, in 1986, with the help of Dan Federman, we extended it to graduates of dental schools other than Harvard. What started as one program here in 1971 is now about 50 around the country. I think it’s really changed the specialty, because it’s practiced by dual-degree people elected to the American College of Surgeons. It really has enhanced the whole specialty.

Do you think that becoming an oral and maxillofacial surgeon enhanced your view that medicine and dentistry are more than just sister disciplines?

I think partly that’s it, but the other thing that’s important is having residency training. Almost all of our students do some kind of residency or graduate work, which is something that I believe in.

You were saying earlier that you always wanted a career that combined practice, research, and teaching. How did that come about?

I was a resident, and then I worked as a research fellow — Walter Guralnick said I needed to get some good research, and I did. I worked with Hermes Grillo, who was a thoracic surgeon, and Jack Burke, who was a physician. And I studied wound healing for about 20 years. I had a laboratory at the Shriners Burn Institute at the MGH.

Was burn repair connected to dentistry?

No, it was just wound healing. We did a lot of wound healing with artificial skins and things of that nature.

Then your research moved to bone graft repair or bone graft survival?

I cared for a lot of head and neck cancer patients and in those days, the radiation methods were not kind to bone. There were conditions that led to loss of bone and bone grafts. I did the first of what’s called a microvascular bone graft, where we’d hook up the blood vessels from the bone graft to the patient so that it could survive radiation. Since I was doing microsurgery, I began repairing injured nerves, trigeminal nerves in particular, that were damaged either by trauma or by surgery, unfortunately. And I still see some of those patients.

How has your thinking evolved about dental education and is that reflected in the curriculum here?

A lot of dental schools are very heavy on procedures. This School was always different because of its alignment with the Medical School. When I was still a student, I remember people coming to observe the educational system here. The University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine was modeled after this School in terms of spending the first two years with the medical students and then moving to the Dental School. Reidar Sognnaes, who was a faculty member here in the ’60s, started the dental school at UCLA in Los Angeles, same kind of thing. Physicians learn very little about the mouth. It’s hard to believe, because there are specialties for the eye, for dermatology. But here, we’ve always emphasized the science and we benefited from being together with the basic scientists, the teachers at the Medical School. There was a report in 1926, called the Gies Report, that said dentistry needs to stay integrated with medicine — separate, but integrated. I’m a great believer in that kind of education.

That’s been your message for decades, right? Are you being heard?

I think so. I’ve been invited to the Harkin Institute in Iowa to speak on integration of oral health into primary care. And I’ve written on it, so I think I’m being heard.

If it comes to fruition — and it seems, at best, a slow process — what would it look like in 20, 30 years?

What we’re trying to do here and at other medical schools is to create a group of dually qualified individuals who’ve had an experience in dental school and who follow that with a combination of oral health residency and primary care residency, because then they’ll think not just of dentistry, but of oral health. I used to teach physical diagnosis to Harvard medical students at Mass. General on the surgical service. And they’d do their patients and they’d do their writeups, and they’d write HEENT — the head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat. And then they’d write PERRLA: pupils equal round — blah, blah, blah. Then: pharynx benign — they went right past the mouth. That led to us giving sessions on the mouth for the medical students rotating at Mass. General and the Brigham. Now, we give a full day to the combined medical and dental class in the first year. But it clearly isn’t enough. The mission of this School for the past five years is to educate global leaders in research, teaching, and practice, and to break down the barriers between medicine and dentistry. That’s not the case for all dental schools. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, some very fine dental schools closed — Wash. U. in St. Louis, Georgetown in D.C., Northwestern in Chicago. Since then there has been a growth of dental schools associated with osteopathic schools, but they’re heavy on the procedures. Oral health suffers from being silo-ized, but the profession likes that. The profession stayed out of Medicare. The two most common questions I get: “Why do dental implants cost so much?” And, “My husband just turned 65, and do you know there are no dental benefits in Medicare?” The American Dental Association just came out against dental benefits, while the AMA supports it.

You’ve described it as kind of a cottage industry. Is that position because of that business model?

And maintaining fee-for-service.

To backtrack to what things might look like 30 years from now: Would you go to your primary care doc, except that doc would also have training in dentistry and do soup to nuts — the mouth and everything else? Or would you have dentists who knew some primary care working maybe in practice with a primary care doc?

I think it would work both ways. But I think dentists could really change and enhance their scope if they wanted to and they weren’t restricted by dental practice acts. They can’t even order a hemoglobin A1C if they think the patient might be diabetic. So I think one of the solutions and what we’re trying to do is to develop a cadre of leaders — young people who are dually trained and educated in the right way who could lead multidisciplinary teams. And one of the things we’re trying to do here with the Medical School Center for Primary Care is establish a so-called “practice of the future” that would be a teaching practice for medical and dental students, maybe pharmacy students all together — because pharmacy’s changed their game. They don’t just dispense pills anymore. It’s a changing scene. There’s a lot said about interprofessional education, but I think interprofessional practice is the important part.

How big a hurdle is resistance within the industry?

Big.

And is that the reason it hasn’t happened yet?

I think that’s a big part. I sit on the American Dental Association Committee on Dental Education and Licensure. I’ve got another year and a half to go. And they’ve been spending a lot of time moving away from this clinical-based licensing exam, where students have to bring in patients and do particular procedures. They could fail because they don’t perform well on one day, even though they did great in dental school. I think the problem with that is we wanted to develop something called an OSCE, Objective Structured Clinical Examination, which Canada has used for years very successfully. We developed this whole thing, with the American Dental Association in it, dental educators, the Student Dental Association — and then someone raised their hand and said, “But how are we going to test their hand skills?” The status quo is hard to break. [Ronald] Heifetz’s book on leadership says there are two kind of transformation: technical and adaptive. Technical transformations are easy — you change a little rule. Adaptive ones are tough. Adaptive always means a loss of something for somebody, and I think that’s what the dental profession is worried about.

Let’s talk about being dean.

Great job.

You have 28 years — longest-serving dean here. What’s been the biggest challenge?

We’re part of the Faculty of Medicine, but in my 28 years, we’ve established quite a bit of independence. I think it’s important to have that independence but maintain the relationship with the Medical School. Accepting the best students, finding the best faculty, being authentic, having the right temperament, all these have been very important.

What part of dentistry has made the greatest advance over the course of your career?

Implantology is tremendously different. It was only in the ’70s that [Swedish physician Per-Ingvar] Brånemark devised the implant. This has led to all sorts of treatment options and changes in curriculum. The implants are very successful, though there are still some problems with them. But it was good for doctors, so it succeeded.

Good for doctors in what way?

Atul Gawande had a piece in The New Yorker several years ago called “Slow Ideas.” He talked about why the introduction of ether anesthesia in 1846 at Mass. General caught on: The surgeons loved it. The information about it traveled faster than if there had been an Internet around. But when [Joseph] Lister introduced the concepts of asepsis and sterilization, it was very, very slow for people to adopt. That’s because the former was good for the doctors, and the second was a chore for the doctors.

With ether, more people will get surgery and surgery will be easier, while for the second one, doctors have to spend more time and be more careful.

Exactly. I think implants are the same way.

Do you remember your first patient?

My first patient here in the Dental School: I made him a denture. When he came back in for one of his checkups, something wasn’t right with the denture. So I asked, “Did you drop them?” He said, no, there were a couple of sore spots, so he put them in the oven to heat them up and see if he could get it to fit better. I had to redo the denture. I’ve had some great patients whom I’ve stayed very close with over the years. I saw a woman two weeks ago, I put a bone graft and a bone plate in 33 years ago. It broke after 33 years.

After 33 years? So you’ll be fixing her — or did?

I did.

What excites you most about the future of dentistry? Is there a particular field or particular advance that you think is going to be a big deal?

I think integrating oral health and primary care can really help the health of this nation and of the world. I think people in underdeveloped areas who have toothaches and walk miles to a health center should be able to get their vaccinations, too. But unless we develop this group of leaders with dual degrees to push integration and educate medical students, we’re not going to succeed.

So you’re saying that the situation here in the developed world is a bit different from the developing world. Here it is how you devise a system that is most efficient, has best practices, and is best for the patient. Whereas in the developing world, there may be one doctor. And if that doctor doesn’t have oral health training, the patients could be out of luck.

The silo-ization of dentistry occurs even in the University. It has to be at least eight years ago, the University had a global health program. And I said, “There’s no oral health in this.” So I got together [former Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Dean] Julio Frenk, a couple of researchers, a couple of people from the Pan-American Health Organization, and we sat down and started a dental global health program, which has been great.

What was the hardest part of your career?

Hardest part? Wow, that’s a tough question. It wasn’t easy to decide to take the dean’s job. I really had a great job here and at Mass. General as department head (of maxillofacial surgery).

What was the deciding factor?

The deciding factor is I thought that someone should lead this School who had gone through its educational system.

What would you tell students who look at your career and wonder how they can be successful in today’s environment?

I don’t know if there’s a formula, but I do think that an academic setting puts one in a position to make change and transformation. It’s very hard to do that through leadership in organizations like the American Dental Association. My favorite quote is from Louis Menand, who wrote a book, “Marketplace of Ideas.” He says — I’m paraphrasing — real transformation does not occur because of the discoveries that are made, but because of how the people who will make the discoveries are educated. That’s why I think these kinds of programs are important. I think important changes to health care in general — and oral health specifically — can best be accomplished through academic institutions.