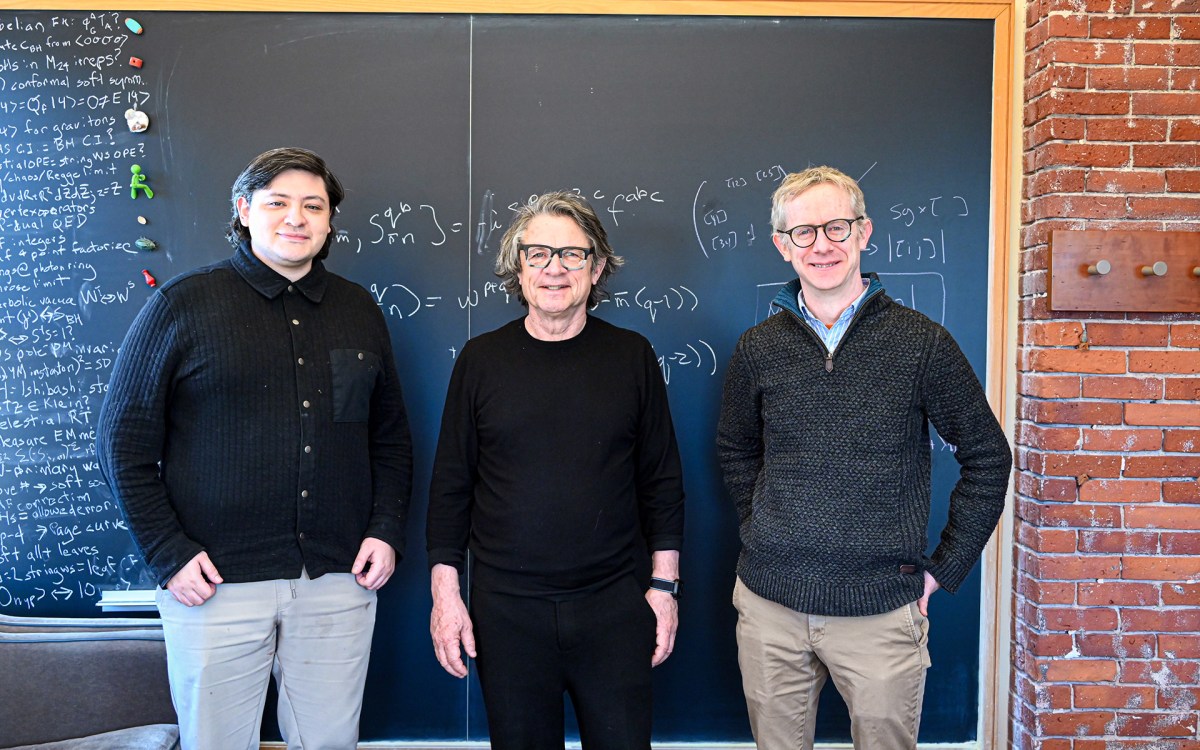

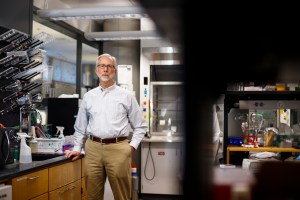

Dustin Tingley.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Numbers tell one story about climate change. People tell another.

Policy expert Dustin Tingley studies transition to renewable energy, knows from work, life how economic shifts rattle through communities

Over the last decade, Dustin Tingley has reconsidered his beliefs about expertise.

As a public policy expert, Tingley has devised quantitative ways to understand the messy problems and sometimes messier datasets that abound in political economy, international trade, and political science. In recent years, he has turned his attention to the transition to renewable energy amid the quickening pace of climate change.

As he has done so, Tingley has found himself shifting focus from datasets that tell a story in numbers to stories told by people experiencing changing economic circumstances and climate-stressed times.

“I came to the realization that there was so much expertise about this topic that was not in academia,” said Tingley, the Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and professor of government in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “You go where the knowledge is, and the knowledge is in the field. The knowledge is in the lived experience of communities and people.”

Tingley hasn’t abandoned data and its power to illuminate in ways beyond the reach of anecdote and personal experience. But he’s also come to recognize that data alone doesn’t tell the full story. Missing in high-level, numbers-driven discussions of things like jobs to be lost in the fossil fuel industry are the community-level impacts of shifts in industries that underpin not just household finances, but also local and regional economies. This includes everything from concerns around infrastructure to downtown retail zones to the ability of local governments to fund things like public safety and schools.

“It’s easy to think about this in terms of fossil-fuel jobs, which are important to focus on, but what that misses is that the local economic tax base depends on it,” said Tingley. “That was not on my radar at all, but it was one of the first things that people would raise. Local economic development officials or county commissioners would show, for example, a picture of their local football stadium. I didn’t have an appreciation of how embedded and suffused all this was.”

The work culminated in 2023’s “Uncertain Futures: How to Unlock the Climate Impasse.” The volume, co-authored with Alexander Gazmararian, relies on interviews, community meetings, and other forums to present an on-the-ground view of climate change and the coming energy transition. Focusing on individuals, business owners, and community leaders, it seeks lessons from those likely to feel the transition most deeply.

“I definitely brought my quantitative knowledge and expertise to bear,” Tingley said. “But the more qualitative interview, the listening and learning, was necessary because my slice of academia did not have the bigger picture.”

Tingley’s shift in perspective was perhaps preordained. Though his work in international relations has largely followed the numbers, a shift to communities in transition echoes the changes that rocked the places where he grew up.

His family’s financial situation improved over time, but they struggled when he was young. They lived in a rural part of North Carolina where furniture-making and tobacco-growing were important industries, both of which would encounter significant challenges. The region’s furniture industry declined due to foreign competition and outsourcing, while tobacco has long been under assault because of health concerns.

He also recalls visits to his father’s family in West Virginia, driving through coal country, with blasted mountaintops and mile-long coal trains. The economic impact of the industry’s decadeslong decline was apparent even to his young eyes, as he watched weathered shacks and cars on blocks in front yards pass by his window.

Tingley has always had an interest in the environment, which he says was piqued by his family’s move to New Jersey in middle school, with the Garden State’s juxtaposition of oil refineries and urban sprawl, fertile farmland and natural Pine Barrens.

But his first academic passion was international affairs. That interest developed in the years around the Cold War’s end, when his North Carolina elementary school had him crouching under his desk during nuclear drills, the Soviet Union collapsed, and later, in high school in the mid-1990s, when protests on the streets highlighted globalization’s inequities.

“I started to become more aware of the world, learning more systematically about war and conflict and the Cold War and international trade — you read stories about protests — I realized there’s a big world out there,” Tingley said.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Tingley studied at the University of Rochester, earning a political science degree and a minor in math. After teaching at a private school in New York for two years, he headed to graduate school at Princeton, where he became more deeply involved in research. The work blended statistics and political science, and he began developing new statistical tools when existing ones weren’t up to handling the complex and often unruly data sets.

“You go where the knowledge is, and the knowledge is in the field. The knowledge is in the lived experience of communities and people.”

“He’s full of energy and interested in a lot of different things,” said Kosuke Imai, one of Tingley’s professors at Princeton who today is professor of government and of statistics at Harvard. “We worked on these statistical methods, but he went on to other research about international trade and how that affects domestic actors. Now he’s on to climate change. He’s quite versatile in terms of being able to understand today’s need.”

Imai said Tingley’s energy is infectious and part of what makes him a good leader. At Princeton, Tingley was captain of the department’s softball team — Imai recalls being pulled from the whiteboard to the diamond on occasion.

At Harvard, Tingley has taken on a more formal leadership role as deputy vice provost for advances in learning, where he has worked to create educational tools and resources for students and co-chaired a study on climate education.

“He has an energy that is contagious to his colleagues, friends, and collaborators, plus he works extremely hard,” Imai said. “He’s also down-to-earth, doesn’t assume anything, and is a very straightforward person.”

After graduating in 2010, Tingley came to Harvard as an assistant professor of government where, over the next few years, he became increasingly interested in climate change. After gaining tenure in 2015, he began to look for climate-related problems to explore.

His research eventually touched on the U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance program, which provides financial support to those who have lost their jobs due to international competition. He began to wonder whether workers displaced by the clean-energy transition might benefit from something similar.

“I thought, all these fossil-fuel people are going to lose their jobs, what are we going to do about them?” Tingley said. “I ran polling on an idea that I called ‘climate adjustment assistance,’ basically asking, ‘Would you support helping fossil-fuel workers transition?’ and bipartisan majorities supported it.”

Since “Uncertain Futures,” Tingley has continued his work. He is part of a cluster of the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability that carries on themes in his book. The work uses community surveys, public hearings, and in-person interviews to gather experiences and opinions on the best way forward.

In August 2024, Tingley and pre-doctoral fellow Ana Martinez authored a report, “Federal Land, Leasing, Energy, and Local Public Finances,” examining how differently the nation handles proceeds from fossil fuel versus wind- and solar-generating facilities.

Proceeds from fossil-fuel extraction on federal land are shared with nearby towns and states and provide important revenue for them. But the report noted that when it comes to renewable energy, the federal government keeps all the money.

The pair conducted a nationwide poll, finding that significant majorities of voters in both parties support sending renewable revenue to local communities, a step that might help build acceptance in the most affected places.

“Just convincing someone that there’s a problem is a totally different thing from putting in place a solution that they can afford,” Tingley said. “People vote with their pocketbooks.”