Roy J. Glauber ’46, who received the Nobel Prize in physics in 2005, passed away on Dec. 26, 2018.

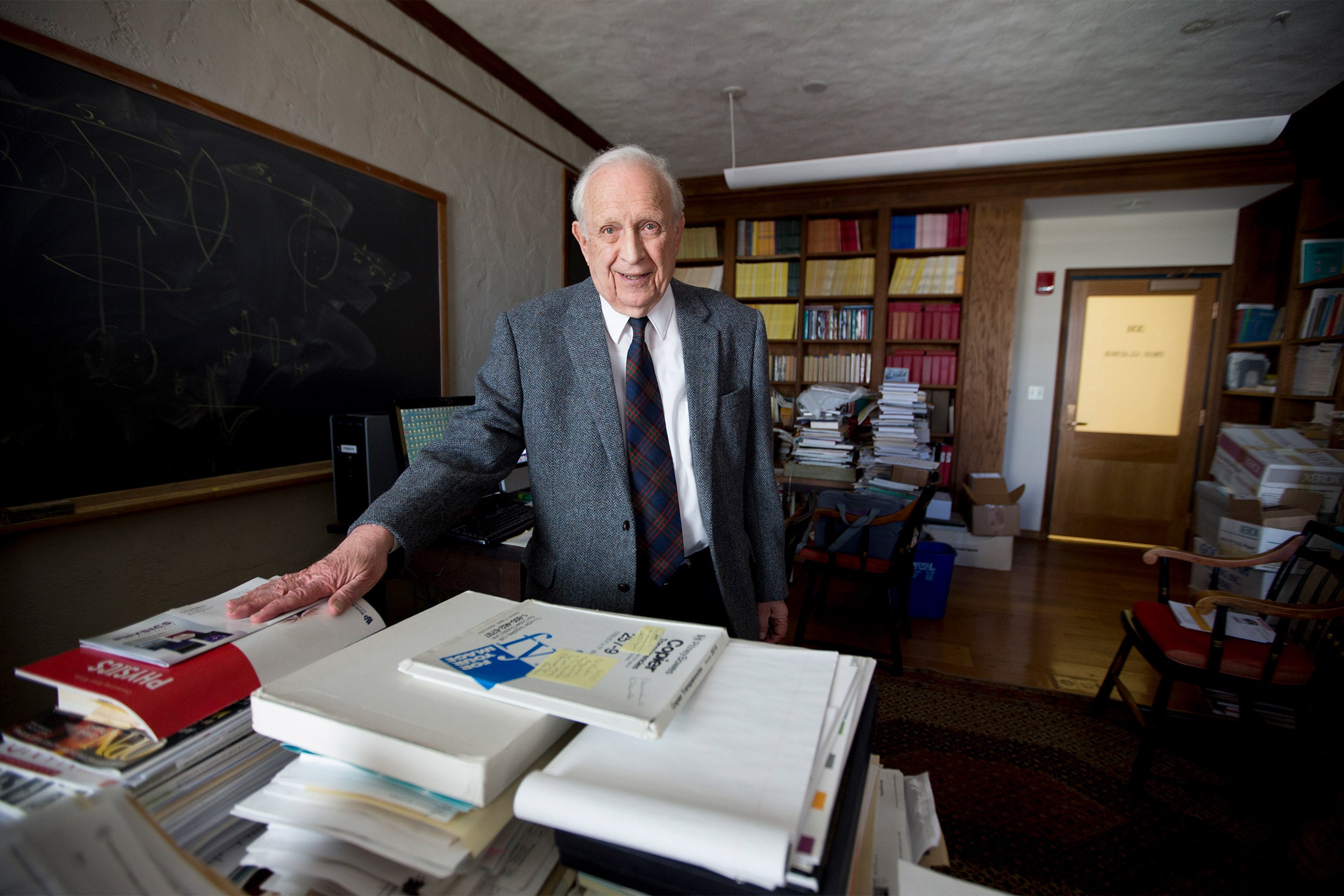

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Nobel physics laureate Roy Glauber dies at 93

Harvard professor laid foundation of quantum optics, worked on Manhattan Project as a teenager

Roy J. Glauber ’46, the pioneering theoretical physicist who received the Nobel Prize in 2005 and was one of the last living scientists to have been present for the dawn of the atomic age, died on Dec. 26, 2018. He was 93.

The research that set Glauber on the path to a Nobel began with his interest in a groundbreaking 1956 experiment that confirmed a key concept of quantum physics — that light was both a particle and a wave — and laid the groundwork for the field. His landmark 1963 paper, “The Quantum Theory of Optical Coherence,” used quantum mechanical tools to transform science’s understanding of light, which previously had only been studied using classical techniques.

“We really did not have a complete understanding of the quantum properties of light, and what Roy’s work laid out was a framework for thinking about that,” said Mikhail Lukin, the George Vasmer Leverett Professor of Physics and co-director of the Quantum Science and Engineering Initiative. “It allowed us to think about these types of questions quantitatively … so I would argue that his work very much laid the groundwork for the field of quantum science and technology that people are talking about right now.”

Lukin said the theories outlined by Glauber opened the door for many scientific discoveries as well as next-generation technologies, including quantum computers and networks and the use of quantum cryptography, which relies on quantum mechanics to create impossible-to-crack codes.

“Those ideas all grow out of this framework that he developed,” Lukin said. “Some people refer to these new developments as the second quantum revolution — the first was about understanding the laws of quantum mechanics. But in this second revolution … the idea is that now that we understand the quantum world and we can actually control it, let’s see what we can use it for. Can we build materials with properties which you design on demand? Can we build quantum computers? Can we build quantum networks where we can send information with absolute security from one side of the country to the other? These types of ideas very much depend on understanding where the classical world ends and the quantum world starts, and that’s where these ideas Roy pioneered and developed become absolutely critical.”

Glauber graduated from the Bronx High School of Science and entered Harvard as a 16-year-old freshman, but left as a sophomore when he was recruited to join the Manhattan Project, where he worked with future Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman to calculate the critical mass of the first atomic bomb. Glauber was later present at the first tests of the bomb.

Following World War II, he returned to Harvard to finish his undergraduate studies and later earn a Ph.D. After receiving his doctorate he was recruited to a position at the Institute for Advanced Study by Robert Oppenheimer, and worked there before returning to Harvard in 1952, where he spent the remainder of his career.

Though he was known for taking his scientific work seriously, friends said Glauber wasn’t without a lighter side. For years, he was “keeper of the broom,” clearing the stage of paper airplanes thrown during the annual Ig Nobel Prize ceremony recognizing unusual or trivial scientific achievements.

One of the few years Glauber missed the Ig Nobel ceremony was in 2005 — because he was in Stockholm collecting his real Nobel.

“I think he took real glee in his role at the Ig Noble ceremony,” said Arthur Jaffe, the Landon T. Clay Professor of Mathematics and Theoretical Science. “He loved to describe with a smile his role as the janitor, sweeping the stage at the end of the performance.”

In his spare time, Jaffe said, Glauber had great interest in classical music. He and his partner, Atholie Rosett, occasionally hosted events for one local performing group in their home.

“People consider him a father of … a huge area of physics that has been very prolific in modern life,” Jaffe said. “He always had a very clear opinion about his evaluation of other scientists. Personally he remained modest; his character did not change at all after the Nobel Prize.”

Irwin Shapiro, the Timken University Professor, knew Glauber for more than six decades, first as a student and later as his colleague. He credits Glauber with ensuring that he got his first job after receiving his Ph.D.

“He was only four years older than I, and he called the head of the MIT Lincoln Laboratory who was thinking of hiring me and suggested, with no uncertainty, that he do so,” Shapiro said.

Though both had grown up in New York, they had never met before Shapiro became Glauber’s first doctoral student.

“One anecdote that made him laugh when I told him was, when I first became his advisee in 1952, I told my mother about it and mentioned Roy’s name as my adviser,” Shapiro recalled. “She somehow mentioned it to her younger sister, who piped up and said, ‘Oh, Felicia’s little boy, Roy!’ I don’t know how my aunt knew Roy’s mother, but somehow they had been friends.”

Glauber is survived by his son, Jeffrey, a daughter, Valerie Glauber Fleishman; a sister, Jacqueline Gordon; Rosett, his companion of 13 years; and five grandchildren.