Art’s shining future

The new glass rooftop that now tops Harvard Art Museums allows natural light to filter down into the courtyard.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Renewed Harvard museums to reopen in a sparkling building, showcasing evocative works

Museums reopen, reimagined

Sitting on the third-floor of the Harvard Art Museums’ arcade last spring, as sunshine spilled in from the new giant skylight above, architect Renzo Piano discussed a quality near to his heart: beauty.

“The frontier between beauty and civic life … is not strong,” said the Italian “master of light and lightness” during a break from touring the renovated Harvard Art Museums, an inspired reimagining of the University’s home for its imposing collection. Musing further, Piano said that museums can help to bridge that divide. “Beauty,” he proposed, “may save the world.”

Architect Renzo Piano (left) tours the museums’ renovation and expansion project with Thomas W. Lentz, the Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

With revamped and expanded galleries, conservation labs, art study center and public spaces, the new museums, which open to the public on Nov. 16, aim to provide visitors with closer, more direct, and more sustained engagement to beautiful works of art. The result of six years of work, the 204,000-square-foot building has two entrances, five floors above ground and three below, a café, a museum store, a 300-seat theater, lecture halls, and teaching galleries.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the ambitious project wasn’t without early critics. Thomas W. Lentz, the Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums, pushed back against doubters who feared that Harvard was simply “rebuilding a very beautiful, static treasure house.”

“My message is this is going to be a very different kind of art museum,” said Lentz. “The experience for viewers is going to be much more dynamic.”

Indeed, dynamism flows from the new design itself, which unites the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum under Piano’s stunning roof. This “glass lantern” showers the Calderwood Courtyard with light, dispersing sunshine into the adjacent arcades and galleries. When the doors open, visitors will enjoy more than 50 new public spaces and galleries containing artworks that have been arranged chronologically, starting with modern and contemporary works on the ground floor and working back through time on the upper floors. About 2,000 works will be on display, many for the first time.

In planning the renovation, Lentz and his team members were determined to maintain each museum’s identity, while ensuring lively dialogue among them. Early planning took into account the institution’s place in the greater Boston museum landscape, its role as an integral component of one of the world’s leading universities, and its commitment to the constituencies it serves, including faculty, students, and the larger community.

“We asked Renzo to design a new kind of laboratory for the fine arts that would support our mission of teaching across disciplines, conducting research, and training museum professionals, and strengthen our role in Cambridge and Boston’s cultural ecosystem,” said Lentz.

The single glass roof symbolizes the coming together of these potent concepts. Lentz said that to accomplish this grand transformation, “We had to take everything apart and put it back together again.”

Directly below the roof sits the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, where the public can glimpse conservators preserving masterworks and making discoveries for future generations. Floor to ceiling glass panes offer visitors insights into how experts gently piece back together a work of ancient Greek pottery, return a 16th century Ottoman dish to its original splendor, or carefully reframe a vivid painting by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Light from the “glass lantern” fills the iconic Calderwood Courtyard. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

There’s a dynamic beauty too in the gallery configurations, and in the imaginative juxtaposition of the artworks within them. Paper, prints, and drawings are now displayed side-by-side with paintings, sculptures, and decorative art. American pieces stand alongside European and Native American material, and ancient classical sculptures depicting the human form recline or stride alongside their 20th century counterparts, creating connections and crosscurrents between collections.

On the third floor, Harvard faculty will engage with art objects, arranging their own visual arguments to support their courses in the museums’ University galleries, which are open to the public. Nearby, in art study centers for each of the three museums, visitors can make appointments to inspect myriad items, including Greek bronzes, Japanese prints, Persian illustrated manuscripts, Rembrandt etchings, and photographs by Diane Arbus.

Treasures through time

A gallery of Buddhist works from the collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum includes 6th-century cave temple sculptures from Tianlongshan, China. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Self-Portrait in Tuxedo,” 1927, by Max Beckmann is part of the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s collection. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The sculptures in a Busch-Reisinger Museum gallery include “Kneeling Youth with a Shell,” 1923, by George Minne (foreground/right). Works by Renée Sintenis, Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, and Käthe Kollwitz are also on view. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A series of prints titled “The Bath,” created between 1890 and 1891 by Mary Cassatt, are in the Fogg Museum. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Summer Scene,” 1869, by Jean Frédéric Bazille is part of the Fogg Museum’s collection. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

View of “Griffin Protome from a Cauldron,” c. 620-590 BCE, in front of “Hydria (water jar) with Siren Attachment,” c. 430-400 BCE, from the collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Canopy of light

That kind of beauty can often be found in the details. Anyone familiar with Piano’s renowned portfolio knows that his go-to building ingredients include glass, steel, and light. In 2013, the architect told an interviewer that he likes to use “the same material to tell a different story.”

At the Harvard Art Museums, that story unfolds under his massive, six-hipped glass rooftop that pulls light down through the central circulation corridor’s arcades and galleries and splashes it onto the bluestone tiles of the courtyard five floors below.

“There was always going to be light in some way, shape, or form because that’s what Renzo does,” said Peter Atkinson, the museums’ director of facilities planning and management, on a sunny rooftop tour.

The bird’s-eye view from five floors up offers a unique look at Piano’s glass crown and his meticulous attention to detail, such as a row of steel grommets rising up the louvered glass in a perfect line, and a functional yet elegant network of ladders and catwalks erected so workers can regularly clean the panes.

Understanding the roof at the Harvard Art Museums

Peter Atkinson, director of facilities planning and management for the Harvard Art Museums, discusses the ‘fly-bys,’ angular points of glass that extend the rooftop’s design skyward. Edited by John McCarthy/Harvard University

The panorama of Harvard’s myriad rooftops also reminds visitors that Piano’s creation is a dramatic addition to the University’s eclectic skyline, “something he spent a long time thinking about,” said Atkinson, who recalled the hours that the 77-year-old architect spent circling the building during construction. “When he would come here, he’d spend more time outside the building than in it. He would walk around; he’d walk all over. He would look down the streets, because he wanted to make sure his building fit the scale of the neighborhood.”

To figure out how to piece the complex roof together, Piano turned to a team of German engineers. The final design was the product of various modifications and alterations because often what looked good on a model “just wasn’t workable” in real life, said Atkinson. “Form” he added, quoting design’s enduring maxim, “follows function.”

Any roof’s most critical function, of course, is to keep the outside outside. In Germany, engineers blasted a small mockup of the roof with wind and water, using an aircraft propeller engine to test its durability. Happily, it passed.

Piano’s roof is also central to the climate in the building. Exterior panes of louvered glass protect an outside layer of shades that help to control the interior temperature and relative humidity. Six pyranometers, small saucer-shaped machines that measure sunlight levels, indicate whether the shades should be raised or lowered to help keep the temperature steady. The roof design is also key to important conservation work. A series of interior shades beneath a second layer of glass can be lowered or raised with a tap on a tablet computer by conservators eager to examine their work in natural light.

This elegant, efficient system, said Atkinson, “was not conceived or designed or built on the fly. It took a long, long time.”

Restore, repeat

Through the years of building restoration and construction, conservators and curators have been carefully examining, repairing, and restoring much of the museums’ extensive collection.

This detailed, delicate work unfolded in the Straus Center, an 80-year-old institution that was the first in the nation to use scientific methods to study artists’ materials and techniques. Piano’s design returns the labs to the building’s uppermost floors, where they can take advantage of the natural light offered by the “glass lantern.” On the museums’ fifth and top level, a suite of sun-drenched, open rooms contains areas for the study and conservation of objects, works on paper, and paintings. One floor down in the Straus Center’s analytical lab, experts determine the chemical compositions of works of art. (The lab includes a vast collection of vivid pigments started by Edward W. Forbes, the center’s founder and former Fogg Museum director.)

In keeping with the museums’ drive for greater transparency, work that once took place behind closed doors is now partially visible through the giant glass windows that look out onto the museums’ new circulation corridor. “We think people will like having a glimpse of our space as much as we like being able to see the galleries and the rest of the museum,” said Angela Chang, the center’s assistant director and conservator of objects and sculpture.

Curious members of the public who knocked on the Straus Center’s door in the past were politely turned away. Now visitors will be able to observe the work from a distance without disturbing those inside. “We have a long history of teaching and presentation, and it makes sense for us to be visible,” said Henry Lie, the center’s director and conservator of objects and sculpture.

On a recent afternoon, Lie carefully looked over a 20th century copy of an item in the museums’ collection, a first-century statuette of the Greek orator Demosthenes. While it isn’t an original and isn’t part of the museums’ collection, a close examination of the convincing replica, bought earlier this year by a museum staff member out of sheer curiosity, revealed important information, said Lie. “It establishes that the copy was made from the work in our collection, which helps to authenticate the museums’ statuette. It’s didactic for the types of technical questions that we have.”

The art of conservation

A delicate touch

Paintings conservator Kate Smith gently restores a work in the center’s paintings lab. Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

How it works

The Straus Center’s director, Henry Lie, discusses the delicate work that takes place in the four labs on the museums’ top floors. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Careful conservation

Tony Sigel, conservator of objects and sculptures, examines delicate, unfired clay sherds from an Asian sculpture. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Conservation cleaning

The Straus Center’s assistant director, Angela Chang, carefully dusts off bits of cobweb and insect casings from an item in the artist Nam June Paik’s collection. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Paper precision

Conservation technician Barbara Owens meticulously mats works on paper. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Complementing the color

In the paintings lab, conservator Teri Hensick adds touches of color to the 19th-century painting “Phaedra and Hippolytus” by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Nearby at another table, Chang gently dusted cobwebs from a large black plastic train engine, one of a series of quirky items from the studio of Nam June Paik, the Korean-American artist considered the founder of video art, which will be displayed in the museums alongside his artwork. Across the room, objects conservator Tony Sigel clicked through the detailed digital documentation of his restoration of an ancient, cracked Greek terracotta kylix, or drinking cup.

Across the hall, paper conservator Penley Knipe readied another delicate work for a bath. Over the years, a non-museum-grade mat had gradually yellowed the recently acquired 1944 black-and-white print “Encounter” by Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher. Surprisingly, one effective way to clean prints, explained Knipe, is to gently wash them in specially conditioned water.

People don’t believe it, she said, but “you really can float paper, or even immerse paper into water.” Such a bath will rinse out the acidic material that discolored the Escher print, returning some “health and lightness to the paper,” and making the image “pop a lot more,” she said.

Paper conservator Penley Knipe prepares a work on paper for a bath in the Straus Center’s paper lab. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

Around the corner in the paintings lab, paintings conservator Teri Hensick gently added touches of color to the 19th-century work “Phaedra and Hippolytus” by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. As with any restoration, making sure the new changes are reversible is critical, said Hensick, who covered a series of fine scratches on the surface with an easily removable paint.

During construction, many of the museums’ paintings were treated to some kind of aesthetic facelift. Some works required nothing more than a good cleaning with hand-made, oversized cotton swabs covered in one of the best fine-art cleaning fluids available: human saliva. Its slightly viscous consistency, pH-neutral balance, and natural enzymes make it “a really effective, very gentle way of releasing grime from the surface of some paintings,” said paintings conservator Kate Smith. Other, more involved treatments included the removal of non-original varnishes that darkened over time and altered some paintings’ original appearances.

“Each treatment was revealing in a different way. Sometimes taking off an amazing yellow varnish just revealed a whole new poetry in a painting,” said Landon and Lavinia Clay Curator Stephan Wolohojian. Like all of the museums’ curators, Wolohojian worked closely with conservators to develop an individualized plan for each painting in his domain. But much of the restoration work didn’t involve the actual paintings at all.

Framing the issue

Since 2012, Allison Jackson, the museums’ first frame conservator, has repaired and refurbished more than 100 frames, ranging from medieval to modern. Jackson’s treatments, from basic cleanings and simple touch-ups to total reconstructions, were completed with a careful eye toward historical accuracy.

An example is “The Actors,” an evocative triptych from the early 1940s by German painter Max Beckmann. While studying a series of old photos of the work, Lynette Roth, Daimler-Benz Associate Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, realized the shiny black frame she always thought looked “out of place” on the work was actually the original frame that had at some point been painted black. Jackson’s fix was simple. She gently stripped off the dark paint, returning the wood to its original light brown.

Roth admitted she was “quite taken” with the refurbished Beckmann work. “The three canvases, designed to stand in a complex and deliberate relationship to one another, now feel more of a piece than when you had this very stark, slightly shiny black frame around each. … It’s gorgeous.”

She called the restoration of more than 20 frames in the Busch-Reisinger’s collection (19 of which were either recreated to replicate the artists’ original frame choices or were made from resized historical frames from the appropriate period) “one of the most important parts of the preparation of our new installation.” Knowing that most visitors likely won’t ever notice the frame work means “we did a good job,” she said. A frame should never detract from or overwhelm a painting, Roth added. It should simply “bolster the overall experience.”

For Jackson, the job of making a frame look like she “didn’t do anything to it” is challenging ― especially when starting from scratch, as with the 17th-century Italian painting by Paolo Finoglia called “Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife.”

Acquired by the museums in the ’60s, the Baroque painting depicting a moment of attempted seduction came edged by a slim black frame more suited to a modern work. After the painting spent years in storage, Wolohojian chose to hang it in the museums’ second-floor arcade. But the odd frame had to go.

After studying other works from the same period, Jackson, Wolohojian, and Danielle Carrabino, Cunningham Curatorial Research Associate in the division of European art, determined the painting’s original frame would have been much wider and far more elaborate. They worked with local craftsman Brett Stevens to design a profile for the frame, which he milled off-site. Once art preparator and handler Steve Mikulka assembled the painting’s new poplar molding, Jackson began making it glow.

Research indicated that a gilded frame likely would have surrounded Finoglia’s striking, 7½- by 6-foot canvas. Before applying the gleaming strips of precious metal, Jackson treated the surface with layers of gesso, a mixture of glue and calcium carbonate, and a layer of bole, a combination of glue and red clay. After sanding those coatings smooth, she began the painstaking process of laying the small leaves of 23.75-karat gold 1/250,000 of an inch thick onto the new frame. It’s delicate work, often done in a confined space to reduce the chances of a draft or an excited exhale carrying away the prized pieces of paper.

Harvard’s frame conservator Allison Jackson gently gilds a new frame with leaves of 23.75-karat gold that are 1/250,000 of an inch thick. Jackson first rubs the brush called a gilders tip against her cheek. The oils from her skin help the gold stick to the brush.

Harvard University

“You don’t want to breathe at the wrong time,” joked Jackson’s helper ― her mother, Sue, a longtime frame conservator and veteran of previous projects whom the museums hired to help add the gold leaf and additional layers of paint and shellac to make the frame “look like it’s been around since 1640.”

Watching the process unfold before her, Carrabino smiled. The new frame will complement the painting perfectly, she said. “This is going to sing for the first time in our collection’s history.”

Shadow paintings

In addition to allowing conservators time to restore works, the museums’ temporary closing offered staffers an extended chance to study and research the collection in detail. That rare window of opportunity proved particularly revealing for one of its most beloved holdings, the Wertheim Collection.

Maurice Wertheim, a 1906 graduate of Harvard College, had a long and varied list of accomplishments: investment banker, philanthropist, amateur chess player, environmentalist, theatergoer and patron. At Harvard, he is perhaps best remembered as a passionate art collector who bequeathed his precious trove of 43 paintings, drawings, and sculptures to the Fogg in 1950. Among the gifts were several French Impressionist, post-Impressionist, and contemporary masterpieces.

But Wertheim stipulated that his collective gift always be displayed together. When the works came off view in 2011, said Cunningham Assistant Curator of European Art Elizabeth Rudy, “It was just an amazing chance to learn anything new about them.”

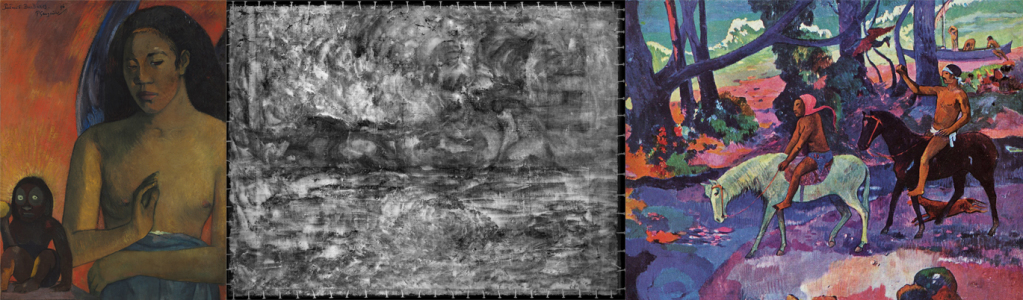

Taking advantage of the latest scientific advances, conservators updated and augmented earlier technical analyses. They scanned Xradiographs of some of the collection’s paintings into a computer, creating a detailed digital roadmap. Other paintings were X-rayed for the first time, including the late 19th-century painting “Poèmes Barbares” by Paul Gauguin. The investigation revealed that the mythological portrait of a winged female figure standing next to a small animal had been keeping a secret: another work painted underneath.

“I must have seen that painting thousands of times over the years, looked at it, conditioned it,” said Hensick of the work completed during Gauguin’s sojourn in the South Pacific. “And while we’d always thought it does have a really odd, textured surface, we’d always chalked that up to it having been folded or rolled, possibly by him to send back from Tahiti.”

At first, the images were almost impossible to decipher — “a kind of a scramble of different brushwork,” said Hensick. But gradually the ghost-like X-rays revealed the faint rise of a mountain, the outline of a horse, and the profile of a person. Ultimately, the staffers determined that the painting underneath was a landscape with a dark and a light horse, each carrying a rider on its back.

“Our systematic technical examination of the Wertheim paintings revealed that Gauguin re-used another painting for ‘Poèmes Barbares.’ Using X-radiography, we discovered a landscape with two riders on horseback, oriented at a 90-degree rotation from the portrait underneath the female portrait. Seeing them is a bit like solving a ‘Where’s Waldo’ game,” said paintings conservator Teri Hensick. “New digital imaging techniques (layering, rotating in Photoshop) helped us see the covered image more clearly.” Above, Gauguin’s “Poèmes Barbares,” is pictured (left) next to the X-radiograph image taken by Harvard conservators (center) and a similar Gauguin painting, “Flight,” (right) painted in 1901 and in the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. (left) Paul Gauguin, “Poèmes Barbares,” 1896. Photo: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College. (middle) “Poèmes Barbares” (X-radiograph).

Photo: Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, © President and Fellows of Harvard College (right) Wikimeida Commons

The team tracked down a series of similar paintings that Gauguin had made around the same time, depicting riders on horseback. They also read letters from his island oasis in which he pleaded for more materials, which suggests that a simple shortage of blank canvases may have led him to cover the first work.

“To find another firmly attributed painting to Gauguin is just tremendous,” said Rudy. “You also get more insight into his working method.”

Echoes of Rothko

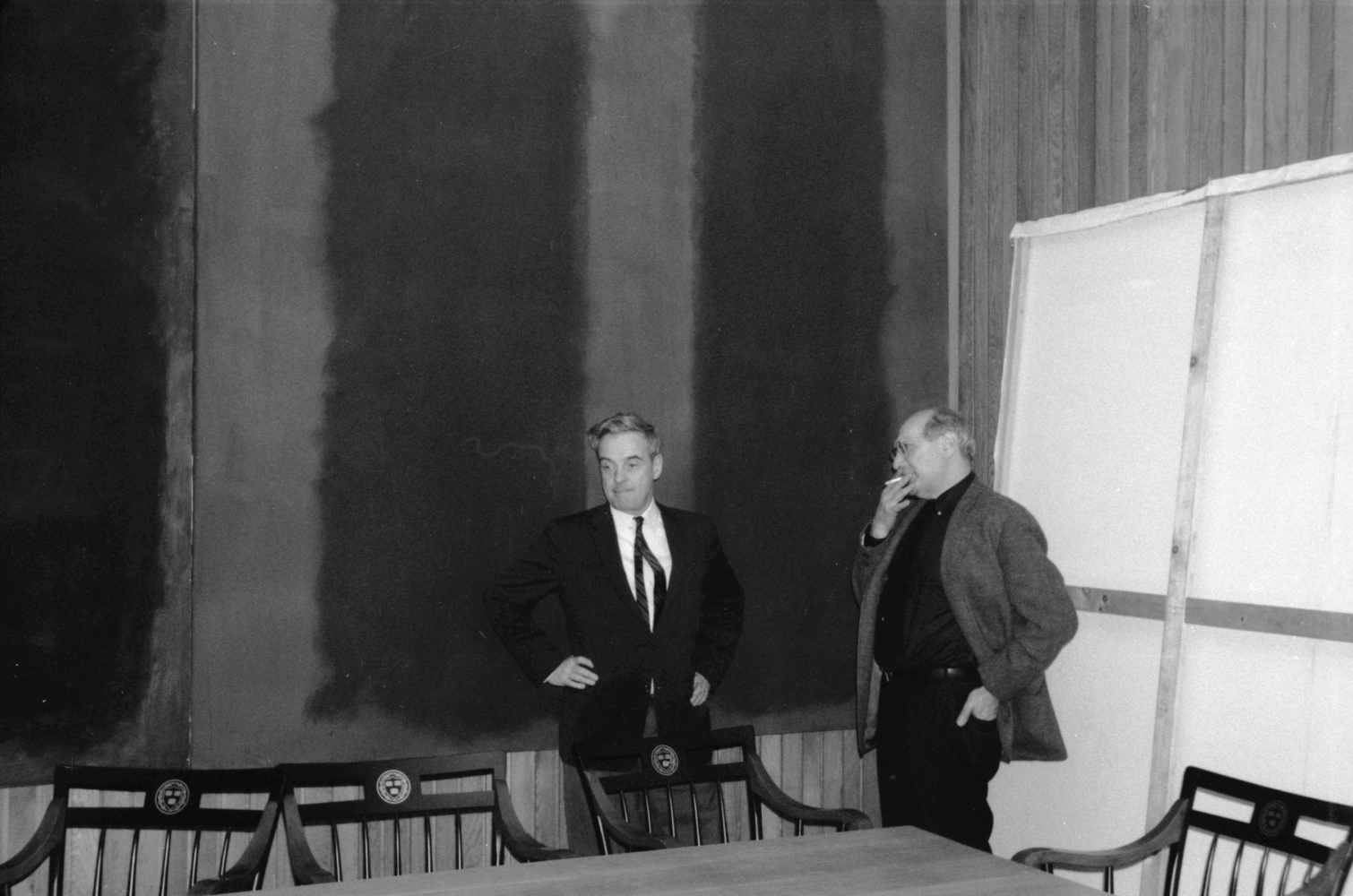

It seems fitting that the restored museums’ inaugural special exhibition features a series of sprawling, carefully restored murals by the abstract expressionist painter Mark Rothko. It also seems fitting that light, so central to the museums’ vision, is key to the murals’ recent restoration.

But the light that revives the original rich hues of Rothko’s giant swatches of color doesn’t come from the sun. When visitors enter the Special Exhibitions Gallery on the third floor for “Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals,” they will see his works as they would have looked more than 50 years ago, color corrected with the help of tinted light cast from five overhead projectors.

In a demonstration of the digital camera-projection system earlier this year, a camera shoots pictures of one of the murals in the gallery. The image is then compared to the restored photograph of the original painting. The information is fed into a computer that uses custom-made software to generate a “compensation image,” which is sent to a projector that then illuminates the mural and restores the color, so it looks as it would have more than 50 years ago. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

Over several years, a team of conservators, scientists, and curators allied sophisticated computer software with determined detective work to restore the appearance of the murals. The Harvard team first analyzed Rothko’s paints and pigments and studied restored Ektachrome photos of the murals to assess their original color. Next, the team enlisted scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to help develop custom-made software that could isolate the paintings’ affected areas and tell the projectors which colored light to emit, pixel by pixel, to augment the missing color.

“This exhibition is fundamentally propositional in nature; it’s really intended to inspire discussion and debate on this new conservation and approach,” Lentz told the Gazette earlier this year during a preview of the new show.

Rothko, known for creating immersive environments for his art, crafted the murals for a special events room on the 10th floor of Harvard’s Smith Campus Center. (The Center was designed by Jose Lluís Sert, then dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design.) Installed in 1964, the giant panels were soon overwhelmed by Sert’s floor-to-ceiling windows, and the colors faded in the sunlight. Officials removed the murals in the late ’70s. They were displayed only a few times in the ensuing decades, and were returned to storage.

Included in the new exhibition will be a series of studies on paper and canvas for the mural series, as well as a sixth mural painted for the commission — brought to Cambridge for installation by Rothko but ultimately not included — on view for the first time.

As with any fine-art restoration, preventing further damage to the work and ensuring that any changes are easily reversible are paramount. The soft light won’t further fade the paintings, said museums’ officials, and the virtual restoration can be undone with the flip of a switch.

The projectors shining light on each of the paintings will be turned off periodically during the exhibition, allowing visitors to see the murals without augmented color. “I think that it’s important to make this distinction,” said Lentz. “We are not restoring the paintings; we are restoring the appearance of the paintings.”

Classics in clay

Piano’s giant jewel box core floods light into the museums. So do two glass galleries on either side of the building’s new Prescott Street facade. In Piano’s winter gardens, windows double as walls. Sun shines in on evocative works, not sensitive to light, that include a collection of terra cotta “sketches,” or bozzetti, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the great Baroque architect and artist largely responsible for defining the look of 17th-century Rome.

In the small glass box adjacent to Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts are a series of delicate small clay statues by the celebrated Italian sculptor. The 13 intricate bozzetti include those made to depict the massive marble angels adorning the Ponte Sant’Angelo, the bridge that spans the Tiber River near the Vatican, and the bronze statues kneeling at the Altar of the Blessed Sacrament in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s “sculptural handwriting

Objects conservator Tony Sigel discusses Bernini’s “sculptural handwriting.” Edited by John McCarthy/Harvard University

A treasure of the Fogg and the largest collection of Bernini’s terra cottas in the world, the sketches were included in a larger Bernini exhibition, co-curated by Sigel, that traveled to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2012 and to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, last year. At the Kimbell, where Piano last year added a wing, he was struck by the bozzettis’ display. They were bathed in natural light and surrounded by the vaulted concrete that architect Louis Kahn — Piano’s mentor — so revered.

Sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s “Head of Saint Jerome,” c. 1661, part of the Fogg Museum’s collection, is one of 13 terra cotta models on view in one of the museums’ two winter garden galleries. Photo: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

System Administrator

Seeing the exhibition, Piano apparently told the museum’s director: “I am building a building at Harvard for these.” That comment got Harvard’s curators thinking.

Back in Cambridge, the sketches fit perfectly in Piano’s winter garden facing the Carpenter Center, where light and Le Corbusier’s concrete architecture reign. Look down and you see a master at work four centuries ago. Look up and across at the Carpenter Center studios and you see new creations coming to life.

In the Art Museums’ intimate glass gallery, cases containing the sketches are arranged at various levels, as they might have appeared in Bernini’s workshop 400 years ago. The sunshine helps to illuminate the sculptor’s prominent hand.

For scholars and art lovers alike, the bozzetti are not simply beautiful works, they are lasting teaching tools that shed important light on Bernini’s motives and methods.

“They chart Bernini’s use of these models to develop his ideas from the earliest conception through to perhaps the final version,” said Sigel, who was part of an extensive research project in the late ’90s to examine the bozzetti in detail.

Look closely, and you can see the artist’s “sculptural handwriting,” preserved in the clay, said Sigel, pointing to a small crescent-shaped mark on the back of the neck of a kneeling angel. The fingernail impression was left when Bernini gave the clay “a pinch between his thumb and forefinger.”

At the base of another sketch, a series of tiny pin marks are trapped in the terra cotta. A compass-like tool, used to gather measurements that would help Bernini and his assistants enlarge the sketches into full-sized sculptures, left the markings behind.

“Kneeling Angel,” 1672, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini is one of several terra cotta sketches in the Harvard Art Museums’ winter garden gallery that reveal the artist’s “sculptural handwriting.” Photo: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

System Administrator

Elsewhere, the sculptor’s fingerprints are clearly visible.

“As you push your finger through the clay, when you pick it up, that’s where the fingerprint is deposited,” said Sigel, who studied clay sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago. “That signals the end of the stroke rather than the beginning.”

In keeping with the museums’ mission of teaching and research, two of Bernini’s precious sculptures have been left out of the display. “It’s critical that we keep some in reserve for the classroom and other projects,” said Wolohojian.

Sigel called the chance to work with and study Bernini’s models so closely “life changing.”

“In some sense,” he said, “I feel as if I’ve been able to look over Bernini’s shoulders as he’s gone about his work.”

Now, visitors can observe the master at work, too.

Art for everyone

Piano’s inviting design allows art lovers and passersby to wander freely through the building’s ground-floor public piazza — which now runs from Prescott to Quincy Street — without an admission ticket. Museum officials are confident that many people will stop along the way. A series of evocative works beckons strollers to explore further.

“One of the things we are hoping will happen, almost just by the contagion of curiosity, is that people will be led to follow different pathways as they experience the art in public spaces,” said Debi Kao, the museums’ chief curator. “They can just have that singular experience, and that will be quite powerful and important. But if it’s really doing its work, the art on view in public spaces will lead visitors into the galleries as well as to other means of gaining expertise about great original works.”

After encountering a work in the Calderwood Courtyard, a visitor might head up a few flights to investigate a corresponding exhibition, find out more about the materials used in a particular installation in the materials lab on the lower level, or examine an artwork up close in the fourth-floor art study center, said Kao.

The great artworks positioned just footsteps away from any entryway also showcase the knitting together of the three component museums. An eclectic selection of art greets visitors who pass through the Quincy Street entrance, including the newly remounted series of intricately carved medieval Romanesque capitals long associated with the Fogg Museum. Nearby, an imposing, sixth-century Chinese stone leonine sculpture invites visitors to take in the Sackler Museum’s rich collection of Asian art in the gallery directly behind. In another corner, “The Crippled Beggar,” German artist Ernst Barlach’s haunting ceramic statue of a frail figure gazing skyward, is an example of the vivid modern and contemporary works on view in the adjacent Busch-Reisinger Museum.

Visitors entering the building from Prescott Street will encounter a group of recent acquisitions that highlight the museums’ increased commitment to collecting time-based and new-media works. “That’s a real focus of our move forward with collection building,” said Roth, “to collect more heavily in those areas and feature artists who are working in a range of media.”

A site-specific work by German artist Rebecca Horn animates one of two double-story walls flanking a pedestrian bridge that leads into the museums. Commissioned for the Busch-Reisinger, Horn’s “Flying Books Under Black Rain Painting” activates the space with a blend of performance and kinetic sculpture. Harvard students soon will watch Horn’s quirky “painting machine” splash black ink on a blank wall as well as on three opening-and-closing books: Fernando Pessoa’s “The Book of Disquiet,” Franz Kafka’s “Amerika,” and James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” Those paint-splattered books will continue to flutter periodically when viewers pass by, activated by motion detectors.

Roth hopes Horn’s work will invite visitors to venture into the University Research Gallery to explore “Rebecca Horn: Work in Progress,” an exhibition of her early performances on film and in photographs, as well as a number of her editioned artworks.

On the adjacent wall, social media takes center stage. In “258 Fake,” 12 video monitors display more than 7,000 rotating images compiled by Ai Weiwei, the contemporary Chinese artist and activist. The photos were originally featured on his popular blog from the 2000s that included his commentary on everything from restaurants to art to architecture to Chinese politics. Eventually, the site proved too provocative for the Chinese government, which shut it down. The intrepid artist quickly found another life for the blog’s visual content with this meditative montage.

But walls and galleries aren’t the only places suited for public art in the new Art Museums. Officials are also considering using the vaulted space above the courtyard to showcase installations that could hang from the intricate interior system of king posts anchoring Piano’s steel and glass roof.

“The courtyard is such a stunning space,” said Kao. “At its center, people can look up and see works of art in the arcade galleries, and the idea of extending that experience into the space above is really exciting.”

Above all, the museums’ driving goal is aligned with Piano’s notion of creating a civic space that acts as a vital bridge connecting the University, the community, and beautiful works of art.

Officials envision the museums becoming a place “of gathering and discourse and discussion and wonder,” said Kao. “We do have this fervent belief in the power of art to be a driver of great ideas of cultural history and cultural memory. And in the end, that’s what it’s really all about.”