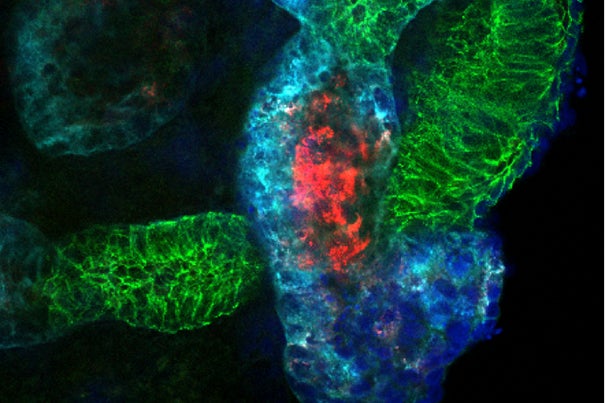

Researchers modeled kidney development and injury in kidney organoids (shown here), demonstrating that the organoid culture system can be used to study mechanisms of human kidney development and toxicity.

Photo courtesy of Ryuji Morizane

Converting skin cells to stem cells creates ‘kidney structures’

New technique offers model for studying disease, progress toward cell therapy

Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) principal faculty at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) have established a highly efficient method for making kidney structures from stem cells derived from skin taken from patients. The kidney structures formed could be used to study abnormalities of kidney development, chronic kidney disease, and the effects of toxic drugs, and could be incorporated into bioengineered devices to treat patients with acute and chronic kidney injury. In the longer term, these methods could hasten progress toward replacing a damaged or diseased kidney with tissue derived from a patient’s own cells.

The work was published in Nature Biotechnology.

“Kidneys are the most commonly transplanted organs, but demand far outweighs supply,” said co-corresponding author Ryuji Morizane, associate biologist in BWH’s Renal Division. Morizane worked in collaboration with HSCI researchers Joseph Bonventre, Albert Lam, and M. Todd Valerius.

“We have converted skin cells to stem cells and developed a highly efficient process to convert these stem cells into kidney structures that resemble those found in a normal human kidney,” Morizane said. “We’re hopeful that this finding will pave the way for the future creation of kidney tissues that could function in a patient and eliminate the need for transplantation from a donor.”

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 9 to11 percent of the U.S. adult population and is a serious public health problem worldwide. Central to the progression of CKD is the gradual and irreversible loss of nephrons, the individual functional units of the kidney. Patients with end-stage kidney disease benefit from treatments such as dialysis and kidney transplantation, but these approaches have several limitations, including the limited supply of compatible organ donors.

While the human kidney does have some capacity to repair itself after injury, it is not able to regenerate new nephrons. In previous studies, researchers have successfully differentiated stem cells into heart, liver, pancreas, or nerve cells by adding certain chemicals, but kidney cells have proven challenging. Using normal kidney development as a roadmap, the investigators developed an efficient method of creating kidney precursor cells that self-assemble into structures that mimic complex structures of the kidney. The research team further tested these organoids — three-dimensional organ structures grown in the lab — and found that they could be used to model kidney development and susceptibility of the kidney tissue to therapeutic drug toxicity. The kidney structures also have the potential to facilitate further studies of how abnormalities occur as the human kidney develops in the uterus and to establish models of disease in which they can be used to test new therapies.

“This new finding could hasten progress to model human disease, find new therapeutic agents, identify patient-specific susceptibility to toxicity of drugs, and may one day result in replacement of human kidney tissue in patients with kidney disease from cells derived from that same patient,” said Bonventre, an HSCI principal faculty member. “This approach is especially attractive because the tissues obtained would be ‘personalized’ and, because of their genetic identity to the patient from whom they were derived, this approach may ultimately lead to tissue replacement without the need for suppression of the immune system.”