‘She had a sense of caring for everybody that she encountered.’

Jane Goodall speaking at Harvard after receiving the Roger Tory Peterson medal in 2007.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Richard Wrangham remembers his teacher and colleague Jane Goodall as a force of science, empathy, and hope

When the scientist and conservationist Jane Goodall died last week, she left behind a transformed understanding of humankind’s relationship to its closest ape cousins — chimpanzees — as well as a legacy that highlights the implications of that relationship in understanding ourselves.

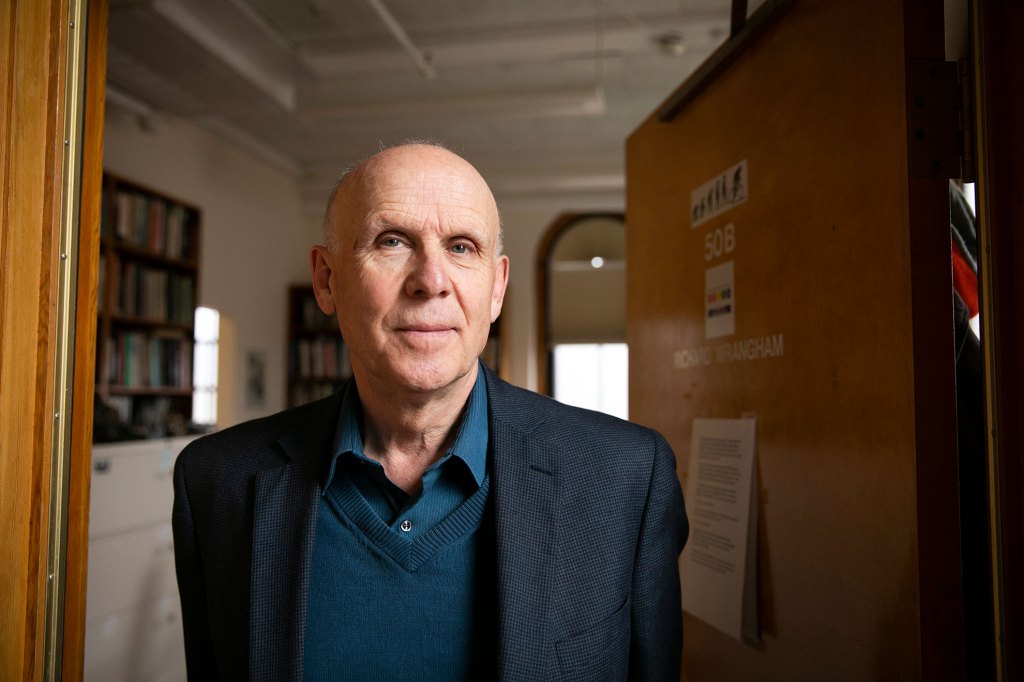

Richard Wrangham, Harvard’s Ruth Moore Professor of Biological Anthropology, emeritus, and a leading researcher of chimp behavior, worked alongside Goodall first as a student and later as a colleague after he founded the Kibale Forest Chimpanzee Project in Uganda. In this edited conversation, he discusses her wider impact as a teacher — not just of colleagues and fellow scientists, but as an exemplar of hope and empathy.

You did graduate work at the Gombe Stream in Tanzania. What was that like?

It was completely magical. I was working in Gombe, a beautiful place with semi-forested, semi-bush, semi-grassland tumbling down to a shining blue lake. Through the hills and valleys roamed about 60 chimpanzees whose behavior was still little understood. Every day was a thrill.

Jane had arrived in 1960 and did a wonderful job of tracking the chimps, finding them and observing them in the wild, before she got to know them as individuals by staying with them in a small camp area. Starting in ’69, students started following the chimps wherever they went. I arrived in 1970 and joined that group. We discovered, for example, that the chimps had a territory that they defended against their neighbors, which raised all sorts of fascinating questions.

At this time Jane was mostly in Serengeti, studying carnivores. She would come to Gombe for a week at a time, which was a joy because she wanted to know all about what was happening with the chimps. She was interested in everything.

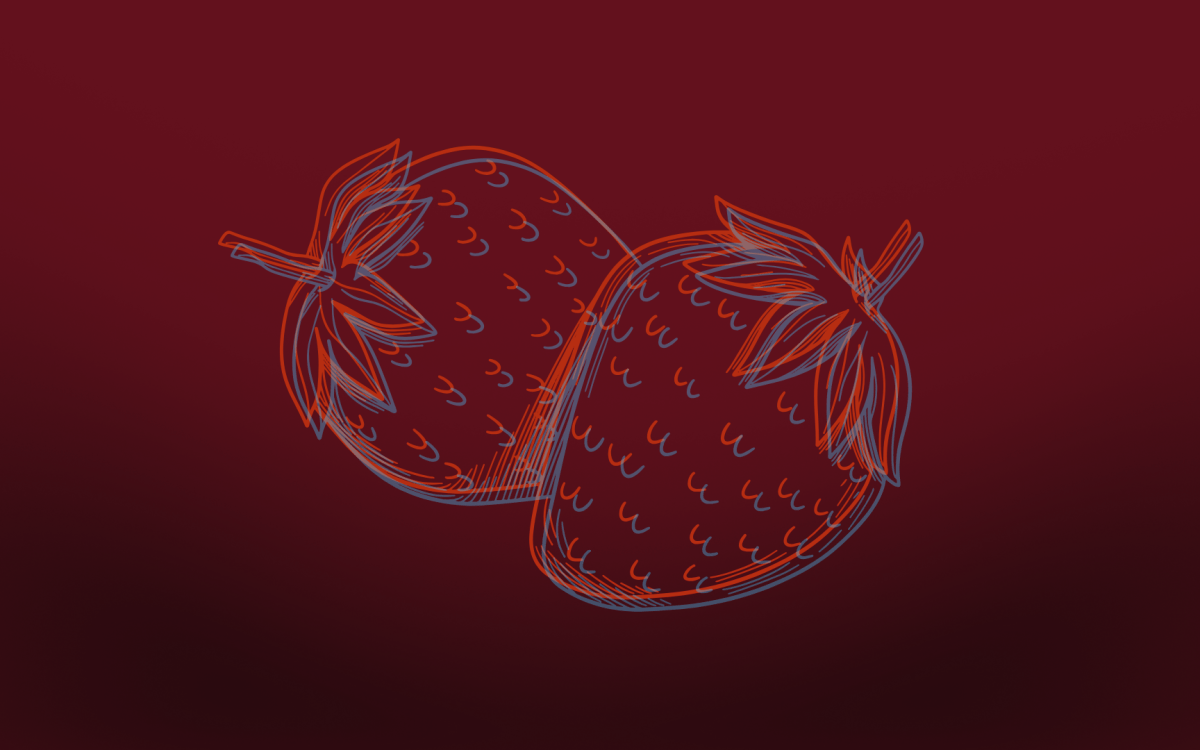

Richard Wrangham.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photograher.

How would you describe her as a person?

Incredibly focused. One thing not everybody appreciates is that Jane was far more than a brave young woman habituating chimps in the forest. She was a really good scientist. She combined meticulous observation with a very good sense of theory. We were very lucky that Jane was one of the first people to study chimpanzees in the wild, because she was so good at it.

Is there a single quality or achievement that you think she should be best known for?

One answer is in terms of what unites her interests, and I think that’s empathy: empathy for chimps, empathy for the people living around the chimp sites — you don’t conserve at the expense of other people — empathy for the world, empathy for creatures in the world. She had a sense of caring for everybody that she encountered.

It’s famous that she was entirely focused on chimpanzee behavior and their natural history until 1986. Her focus changed as a result of a Chicago conference called “Understanding Chimpanzees.” She heard the conservation session and realized that chimps were in trouble. She learned more about the cruel ways in which chimps were often held in captivity and from then on, it was conservation and care that mattered to her far more than research. I think it’s part of the reason she was so successful. She was dauntingly single-minded.

Her work and yours have transformed our understanding of humanity’s closest primate cousin. What do we know now that we didn’t know then?

When Jane began her work in the 1960s, there was no reason to think that any of the great apes were more significant for understanding human evolution than any other, but she discovered far more similarity in the behavior of chimpanzees and humans than between humans and what was known then about gorillas and orangutans and bonobos.

DNA research would later show that chimpanzees are more closely related to humans than they are to gorillas. Her behavioral discoveries of tool-making, tool-using, food-sharing, hunting, warlike behavior, as well as the astonishing intimacy of the mother-infant relationships — things that unite humans and chimps — anticipated the DNA revolution.

People started taking far more seriously the notion that there is an underlying biological influence on human behavior. She also helped convince scientists in general that chimps had far more similarity to us in their emotional lives, in their capacity for feeling, and in their ability to think, than any wild animal had been shown to have.

Richard W. Wrangham (left) presenting Goodall with the Roger Tory Peterson medal in 2007.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Goodall receives the 2003 Global Environmental Citizen Award from Eric Chivian, who was the director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard.

Harvard file photo

Has that work changed our treatment of chimpanzees?

It’s had enormous effects. There were hundreds of chimpanzees in medical facilities in the middle of the last century that now have been released into sanctuaries, where they are nurtured relatively comfortably into their old age without being forced into tiny solitary cages and being the subject of stressful medical experiments.

Some of the coverage has characterized her as an optimist, which seems a bit surprising, given humanity’s assault on nature. Do you agree that she was?

She absolutely felt that it was important for her to be an optimist because people need hope. People need to be motivated to do good things: good for themselves, good for the planet, good for their communities, good for nature. The books that she wrote in the last two decades with “hope” in the title reflect a very conscious determination to keep hope alive. What did she really think? There’s no question the difficulties got to her, but at the same time, I think that she genuinely felt that there are reasons for hope. One of the most important sources of hope for her was the indomitable human spirit. If you can remind people that if you try hard enough you can do anything — her mother’s message — then good things will happen.

Do you share her optimism?

I am not an optimist about maintaining anything like the level of nature that we have now. I see the human species in an unstoppable takeover of the great majority of nature in the world. I think that the hope for the future of our wild places is to focus on the big places that will remain the source for as many animals and plants as we can keep alive. Kibale forest is the biggest forest in Uganda and it’s not very big. It’s only about 250 square miles.

The hope is that we can keep countries thinking that these special places are worth saving. I worry that if we spend too much time focused on saving every little forest, we’ll lose the big picture. But I can feel Jane looking over my shoulder saying, “You shouldn’t say that.” She would say, “You just passionately fight for every little forest, and maybe, out of that fight, more energy comes to save the big ones too.”