A real butterfly effect

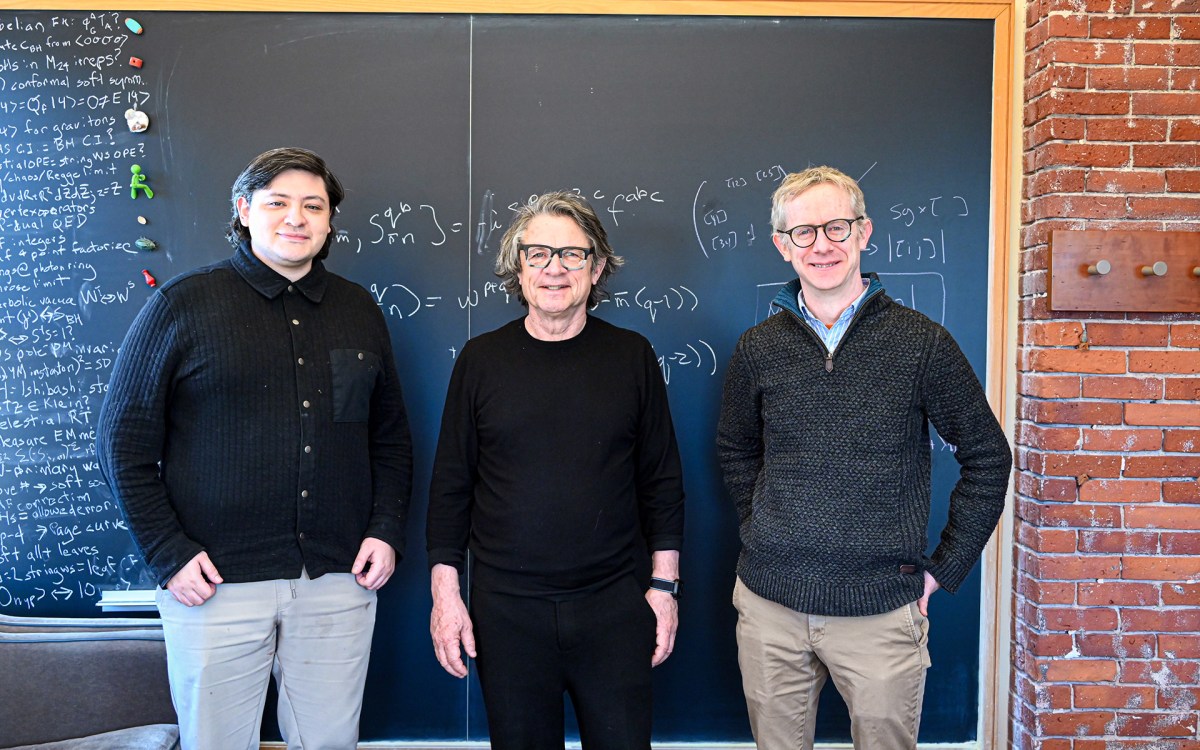

Andrew Berry.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Saga that winds through centuries, continents results in newly recognized species being named in honor of Harvard biologist

This is a tale of scholarly obsession. It involves a burning ship, a jungle-exploring Victorian naturalist, a Harvard biologist, and a rare butterfly.

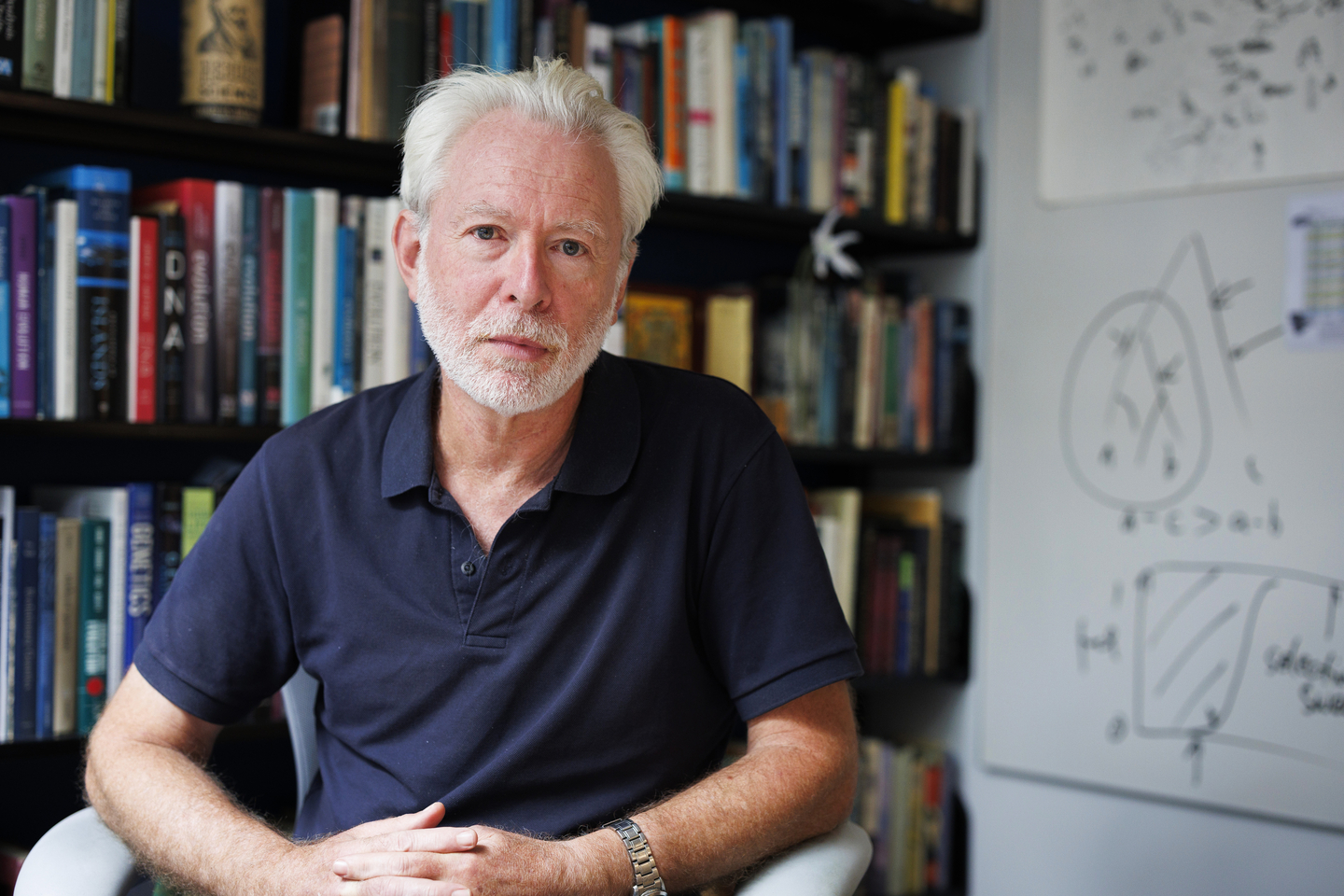

Evolutionary biologist Andrew Berry is a scholar of Alfred Russel Wallace, a pioneering evolutionist overshadowed by Charles Darwin.

Over the years he has collected memorabilia that connect him to his scientific hero, including a rare first edition of travelogues, an autographed letter, and an original 19th-century map.

Now Berry can claim an even rarer link: A previously-unknown butterfly species collected by Wallace in the Amazon — and forgotten in museum drawers for more than 150 years — has been designated as a new species named in his honor.

“I’m absolutely thrilled, sad though it is to be so pathetically vain about having a little brown butterfly named after you,” said Berry as he sat in his book-lined office beside a colorful model of his namesake butterfly, Euptychia andrewberryi. “Seeing my excitement, you might well think, ‘Get a life, man!’”

How that tropical butterfly landed on the desk of a wry English biologist is a scientific saga that winds through centuries across Brazil, the Atlantic Ocean, London, the Harvard campus — and began for Berry with a writing assignment.

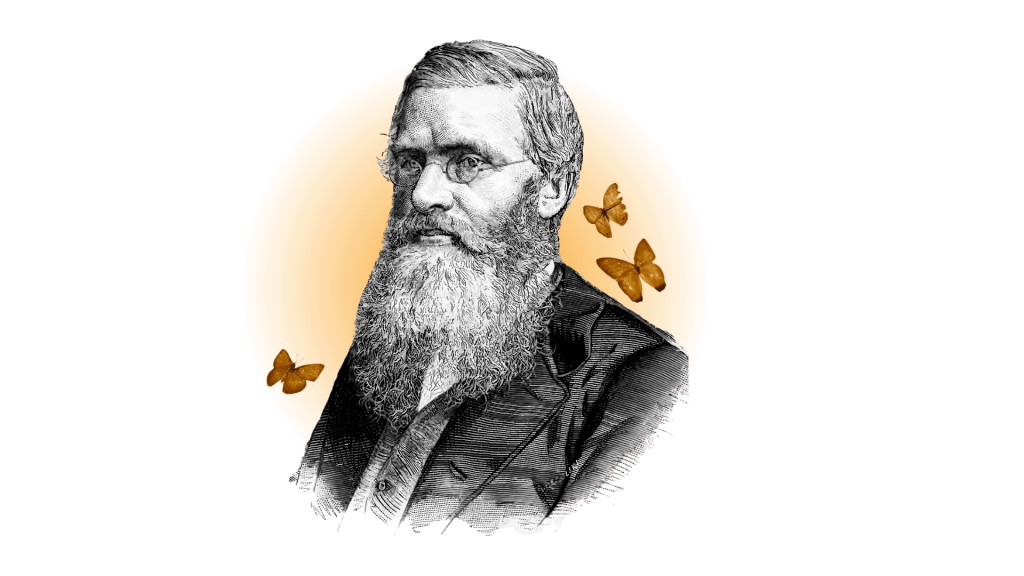

Alfred Russel Wallace.

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Wallace, who was born in Wales in 1823, proposed his own theory of evolution by natural selection at the same time as Charles Darwin in 1858. For a variety of reasons, Darwin became credited as the father of evolutionary biology, and Wallace went down in history as an also-ran.

Yet Wallace was a trailblazing naturalist in his own right, credited with many other major scientific achievements. He fathered the field of biogeography and recognized a difference in fauna that distinguished Asia from Australia, New Guinea, and the Pacific islands — a boundary now called the “Wallace Line.”

In 1848, Wallace and fellow entomologist Henry Walter Bates sailed for Brazil to explore the Amazon and collect insects and other species.

Four years later, Wallace was returning to England when his ship caught fire during the Atlantic crossing, and nearly all his collections were lost. Wallace and his fellow survivors spent 10 days in lifeboats before being rescued.

Fortunately, Wallace had shipped back a few crates of specimens before the ill-fated voyage. Among them were some butterflies from Brazil.

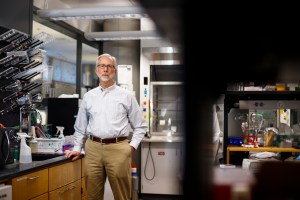

Fast-forward to the current century. Shinichi Nakahara, an associate of entomology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, is an expert on butterfly taxonomy and co-author of the vibrantly-illustrated guidebook “Butterflies of the World.”

He also spent a decade researching a monograph on the genus Euptychia, a group of butterflies from South America and Central America. Poring over collections around the globe, he found the butterflies collected by Wallace and Bates at the Museum of Natural History in London.

Andrew Berry explores the butterfly collections.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Life-sized model of the colorful butterfly Euptychia andrewberryi, otherwise known as “Andrew Berry’s Black-eyed Satyr” on his desk.

Butterflies in the collections at the MCZ.

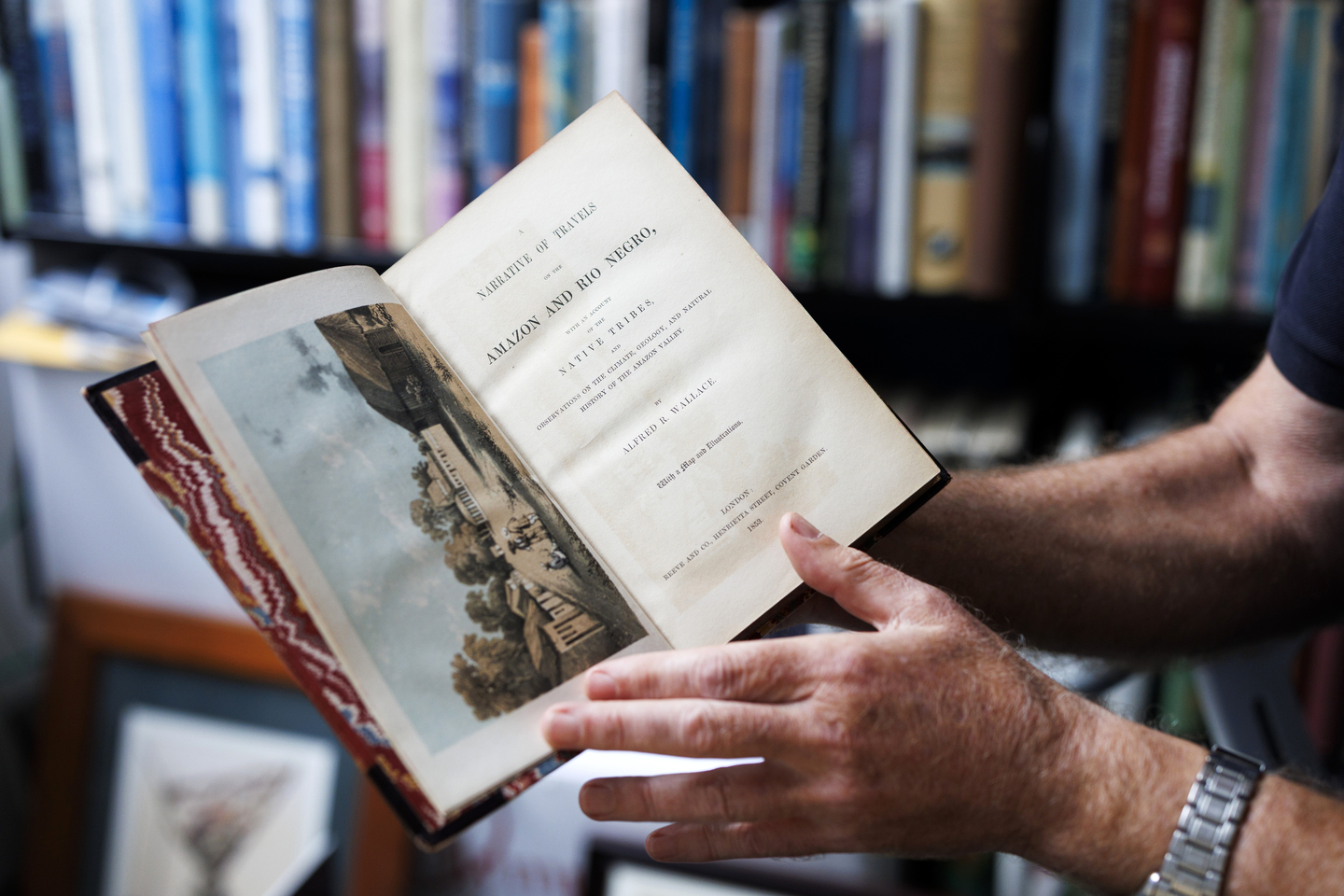

“A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro” by Alfred R. Wallace.

A number of those specimens were classified as the pitch brown black-eyed satyr (Euptychia picea). But Nakahara recognized that five were anatomically distinct and belonged to a new species, one previously unknown to science.

He had a good candidate for a new name — an amusing character who had given him a deeper appreciation of Wallace.

Enter Berry, who is now assistant head tutor of integrative biology and lecturer on organismic and evolutionary biology.

Berry has worn many hats as a biologist. He chased giant rats through the jungles of New Guinea, studied the genetics of fruit flies, and (bear in mind this is not a strict ranking of priorities) mentored generations of undergraduate biology students. He co-authored a book with the Nobel laureate geneticist James Watson and has written extensively about the history of science.

Near the turn of the millennium, he was fatefully assigned to write about Wallace for the London Review of Books and found himself enraptured. He went on to write numerous essays on Wallace and publish a collection of his writings.

“You can’t read Wallace and not fall in love with him, partly because he’s such a fantastic writer,” said Berry. “Then there’s the underdog piece — here’s the guy who co-discovered the theory that we trumpet, and yet he basically dropped off the map.”

“You can’t read Wallace and not fall in love with him, partly because he’s such a fantastic writer. Then there’s the underdog piece — here’s the guy who co-discovered the theory that we trumpet, and yet he basically dropped off the map.”

Andrew Berry

Nakahara felt that such a scholar deserved his own species.

When he first arrived in Cambridge, Nakahara stayed at the house of his faculty sponsor, Naomi Pierce, curator of lepidoptera in the MCZ and Sidney A. and John H. Hessel Professor of Biology, who also happens to be married to Berry.

Nakahara discovered that breakfast in the household involved generous servings of Wallace discussion.

“His contribution is bringing Wallace to people’s attention, because Wallace is this person who’s famous for not being famous,” said Nakahara. “Andrew is very good at explaining the importance of these early naturalists and Victorian biologists, and he is very engaging.”

Having a butterfly named in his honor — better yet, one collected by Wallace and Bates — makes Berry’s heart flutter. One student, Amanda Dynak ’24, made a model of his eponymous species as a gift.

“Andrew is over the moon about it,” said Pierce with a laugh. “I just think it’s a fantastic story, because Andrew is passionate about Alfred Russel Wallace, and has been for a while — in fact, long before Wallace became popular.”

But Berry cannot claim any special distinction in his house. His wife already has three species named after her, including zombie-ant fungus, a brain-hijacking parasite.

“She’s way ahead of me,” he said.