‘Turning information into something physical’

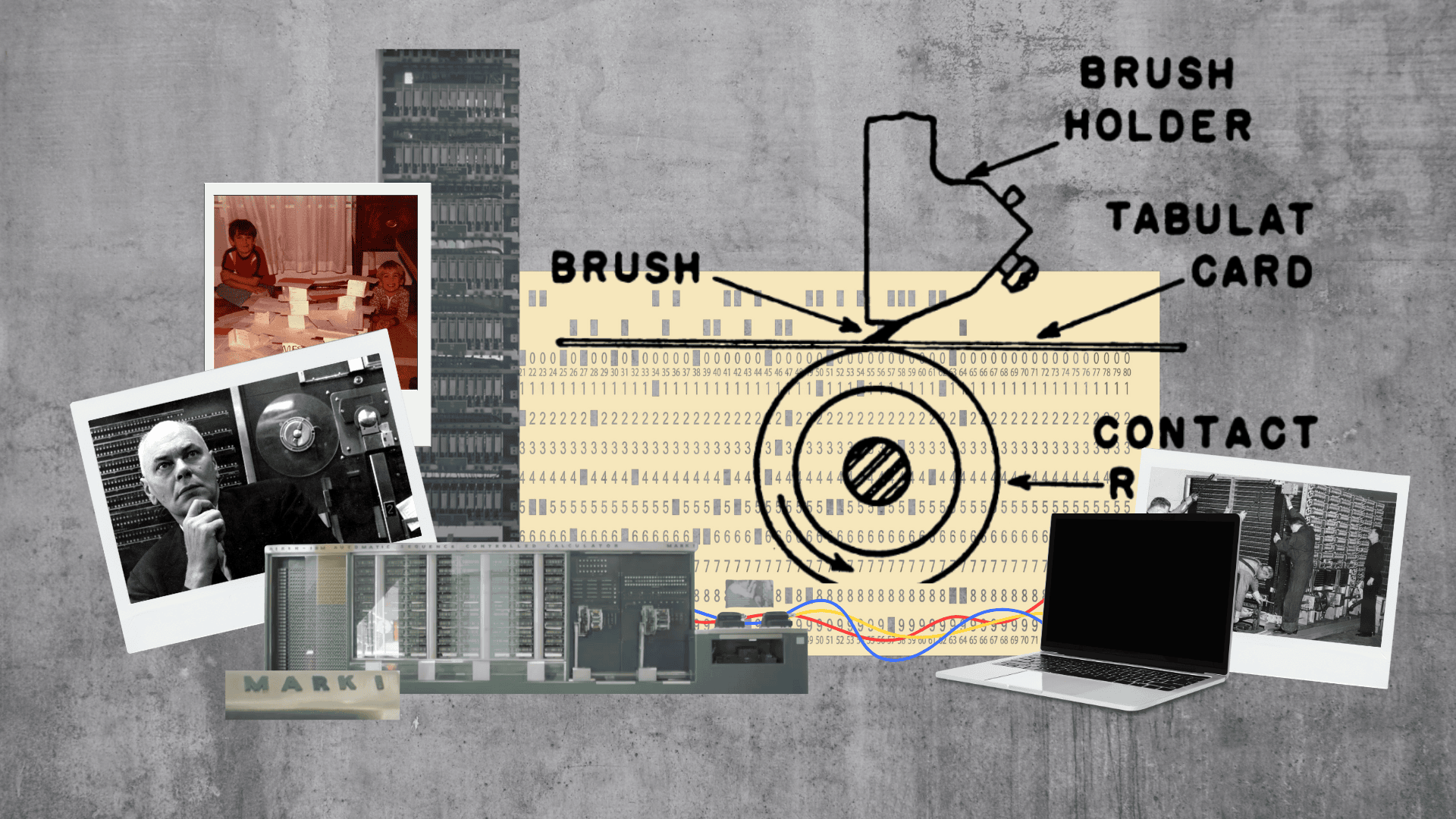

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Houghton exhibit looks at how punched cards — invented 300 years ago to streamline weaving — led to modern computing

The punched card, a paper instrument invented 300 years ago to automate looms, helped create a technology that most of us today can’t live without: computers.

A new Houghton Library exhibition — “The Punched Card from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age” — on view in the library’s lobby through the end of the summer, traces the technology’s history through three works: a book from 1886 woven entirely with a punched card loom; the writing of mathematician Ada Lovelace on the punched card’s computer capabilities; and a 1940s manual on using a punched card computer.

“Computers now permeate almost every aspect of our society,” said the exhibition’s curator, John Overholt. “It’s interesting to learn more about the roots of things that feel very commonplace and widespread these days … to learn how those things evolved over time can provide new insights.”

Punched cards, or punch cards as they are often called, are thought to have originated in 1725, when French silk weaver Basile Bouchon invented the use of a paper tape with punched holes to automate the work of a loom. But perhaps the best-known early example comes from French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard, who in the early 19th century used a series of punched cards to create intricate brocade patterns. Each card had holes threaded to create a single row of design.

Historians think the first time the technology was used for data collection and analyzing was in the late 1880s, when American engineer Herman Hollerith created punched cards for gathering statistical information for the U.S. Census.

“That’s the thing computer historians are most likely to fight about — what the cutoff is,” said Marc Aidinoff, who teaches the history of technology at Harvard. “You get some people who say, ‘Well actually, programming a loom is not that different from computing. It’s putting in directions.’”

Aidinoff added that there is one thing that all tech historians can agree on: “There is no computing without punch cards. When you think of what a semiconductor is doing, it’s really a very similar system to a punch card, just at a vastly more complex scale.”

The earliest use of punched cards to process Census data drastically sped up the time to count results, marking a milestone on the path to modern computing. Hollerith’s company — which started as the Tabulating Machine Company based out of Washington, D.C. — would go on to become computer giant IBM.

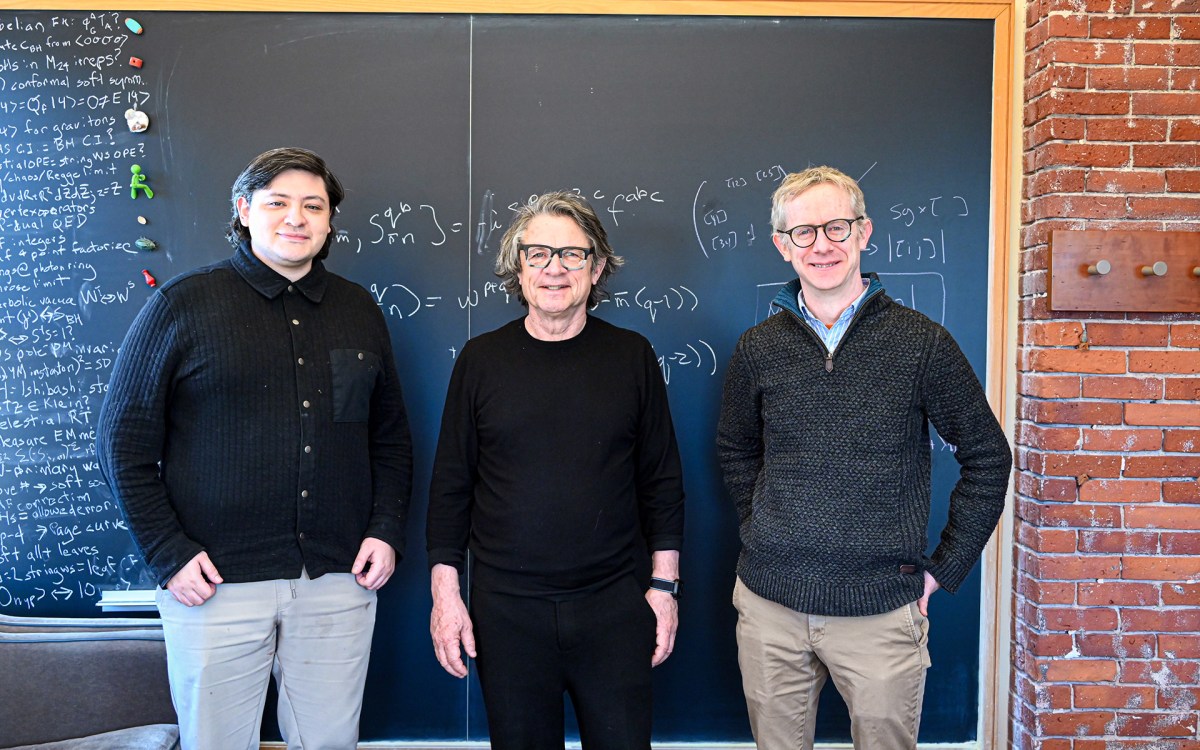

At Harvard, graduate student Howard Aiken designed the Mark I in 1937 — a first-of-its-kind computer able to make a wide array of calculations using punched paper tape.

Aiken partnered with IBM engineers to develop the machine, and after five years Mark I was delivered to Harvard, where it was operated by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships for military purposes over the next decade.

Punched card computing continued throughout the next several decades — improving alongside evolving microprocessing and memory capabilities.

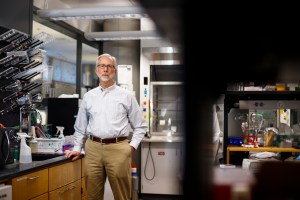

Overholt, curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at Houghton, remembers the discarded punched cards his mom would bring home from her job at IBM throughout the 1960s.

Exhibit curator John Overholt used to play with the discarded punched cards his mom would bring home from her job at IBM throughout the 1960s.

Photo courtesy of John Overholt

“She would bring home punch cards that had been used to program computers for us to play with and build little card houses out of,” he said.

Today, Harvard is home to supercomputers that make punch card computers look like an abacus. But at Houghton, you can see the seeds of innovation that started it all.

“Present-day computer technology has moved in new directions but encoding in ones and zeros and bits and bytes is still pretty fundamental to the way computers work,” Overholt said. “It’s hard for me to put myself in the position of what somebody 300 years ago would have imagined about computers, but I’m sure it was clear right away that it was a very powerful tool for turning information into something physical.”

“The Punched Card from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age” will be on view in the Houghton Library lobby through the end of summer. Mark I is on display in the East Atrium of Harvard’s Science and Engineering Complex in Allston.