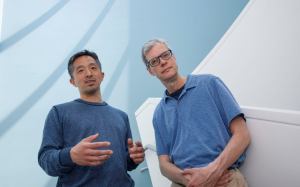

Joseph Drew Lanham (left) interviews fellow ecologist Carl Safina during a recent Harvard talk about Safina’s book “Alfie and Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Screech owl wisdom

‘Alfie and Me’ ecologist on what he learned as he bonded with bird

It took an ailing screech owl to teach a scientist the value of up-close-and-personal study.

In a talk Monday at the Science Center, Carl Safina, an ecologist at Stony Brook University and author of several books about humanity’s relationship with nature, recalled that the chick was found on a friend’s lawn as the pandemic was tightening its grip on the world. In the picture Safina received, the bird looked beyond saving.

“How did it die?” he asked.

“It was just a downy little, dying thing,” Safina, whose most recent book is “Alfie and Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe,” said in his Harvard talk, which was sponsored by the FAS Division of Science, Harvard Library, and the Harvard Book Store and included questions from Clemson University ecologist Joseph Drew Lanham.

Safina and his wife, Patricia, took in the little bird of prey. They planned to nurse it back to health and then perform a “soft release,” in which the animal is set loose but stays nearby, supported with food while it learns the ropes of wild bird life.

But the owlet’s flight feathers didn’t grow in properly, leaving it grounded for months after it should have fledged. Safina delayed the release further to ensure the bird would properly molt — critical to renew feathers that keep birds warm and enable flight. Over those extended months, Safina got to know Alfie in ways that moved and changed him and his wife.

“An owl found me and then I was watching ‘an’ owl,” he said. “It was no longer an owl after a while, it was ‘she,’ because she had a history with us. … This little owl, who was with us much longer than we thought she would be, became an individual to us by that history and all those interactions.”

“It was no longer an owl after a while, it was ‘she,’ because she had a history with us.”

The bond with Alfie strengthened to the point that, when she was finally released, she created a territory with Safina’s Long Island home at its center. Safina was able to spend hours each day observing her in the woods as she learned to take care of herself in the wild, meet two mates, and raise chicks of her own.

When he heard Alfie calling, Safina said, he’d call back and she’d land nearby. Their closeness allowed him to learn more things about screech owls than is generally known. Field guides, for example, describe two known calls but he identified six, some of which you have to be quite close to hear. The relationship also opened a window for Safina onto personality differences between Alfie and her mates.

Lanham pointed out that Safina’s approach to Alfie — including the act of naming her — ran counter to widespread scientific practice. Safina said he wasn’t concerned about violating convention, particularly if something interesting like individual personality differences among owls could be learned.

“I’m interested in knowing what really exists, which is the basic purpose of science,” Safina said, adding that field research has documented personality differences among individuals of species from chimpanzees to elephants to wolves. “Every time they look for it, they find it.”

In the end, the experience caused Safina to ponder more deeply the differences between humankind’s relationship with nature writ large versus the kind of personal connection he was able to feel with a wild individual.

“What I learned from Alfie is that all sentient beings seek a feeling of well-being and freedom of movement,” Safina said. “That’s a guide to what’s right and what’s wrong to me.”