Wounded Black men were taken to the Brady Theater near the Greenwood District, an affluent Black community that was destroyed by a white mob in 1921.

Photo courtesy of the Greenwood Cultural Center/Public Domain

Recalling the Tulsa race massacre, and calling for reparations

Rights activists, academics remember 1921 assault, focus on what remains to be done

The upcoming centennial of the Tulsa race massacre brings a grim reminder of America’s troubled history with African Americans with a particular resonance, given the current national reckoning sparked by the unjust police killing of George Floyd and other people of color. In a virtual event this week sponsored by the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, a panel of academics and human rights activists discussed the past and focused on the work that remains.

On May 31, 1921, armed white mobs began a deadly assault on Tulsa’s affluent Greenwood district, popularly known as the Black Wall Street. It was sparked by an accusation that a young Black man named Dick Rowland had threatened or possibly assaulted a white woman on an elevator. Charges against Rowland would eventually be dropped. But the rumor was enough that rioting whites descended on the Black district, killing as many as 300 African Americans, injuring hundreds, leaving thousands homeless, and burning hundreds of businesses, homes, churches, schools, and other buildings to the ground.

In the wake of the massacre, the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan continued to flourish; police and many other records of the event vanished; and no public memorials or commemorative events occurred in Tulsa for decades.

The anniversary held special personal meaning for Wednesday’s first speaker, Regina Goodwin, an Oklahoma state representative and Black Caucus chair. Born and raised in the Greenwood area, she had a great-grandmother and great-grandfather who survived the massacre. “The history and the lessons of that period are with me every day. You can talk about a new kind of massacre if you will, when it comes to the erasing of a culture and the particular kinds of businesses that once were,” she said, referring to gentrification in and around Greenwood that threatens to rob the district of its historic identity.

Her ancestors, she said, were among the first to call for reparations after the assault, and she said that battle continues in the efforts to pass federal H.R.40 (an act that would establish a Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans). “That’s where we are: We’re at a crossroads in America where racism has been amplified, the same racism that triggered the total devastation of Greenwood,” she said. “We have to grapple today with the question of race. When are we going to stop just hearing the remedies and start enacting good policy?”

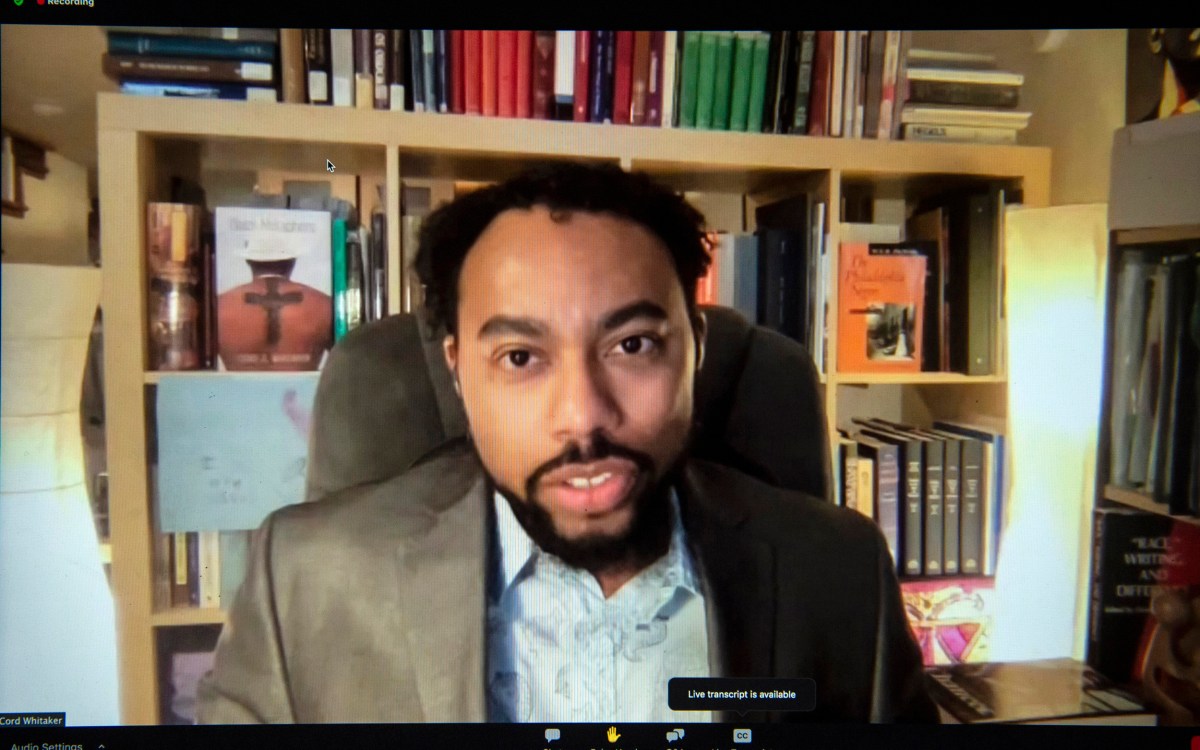

Regina Goodwin and Karlos Hill speak during the panel discussion.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Each of the panelists echoed the same sentiment, that our times call for concrete reparations and not just words. Karlos Hill, who chairs the Department of African and African-American Studies at the University of Oklahoma, underlined that argument by sharing some of his own research — particularly some powerful photos of the Tulsa devastation. “Even for an historian of racial violence, I was shocked when I really learned the depth of the viciousness,” he said. Both the photos and survivors’ testimony, he said, undercut the white supremacist narrative of the Tulsa death and destruction were the result of “Negro insurrection.”

“Once I understood the scope of this I realized it was a community lynching … and we could even look at this as an attempted expulsion of Black people from Tulsa,” Hill said. This made reparations all the more necessary, he said. “If the 100th anniversary is to mean anything, it should mean us mustering the courage for once to do right by America’s victims of white supremacist violence.”

Dreisen Heath, a researcher and advocate in Human Rights Watch’s U.S. program, was even more specific. She said reparations could start with recognizing unfulfilled promises that Tulsa made to the Black community after the massacre, including the revitalization of Greenwood. “Reparations are the right thing to do: financial reparations to the survivors and to the descendants. And an economic enterprise zone — not one that doesn’t benefit Black Tulsans directly, but one that is made in their likeness and image, with their consultation from start to finish.” She also called for a wide range of actions, including proper burial of the massacre’s victims and a more equitable health care system in Tulsa. “We cannot pass up this opportunity to do right, and doing right is comprehensive reparations.”

More like this

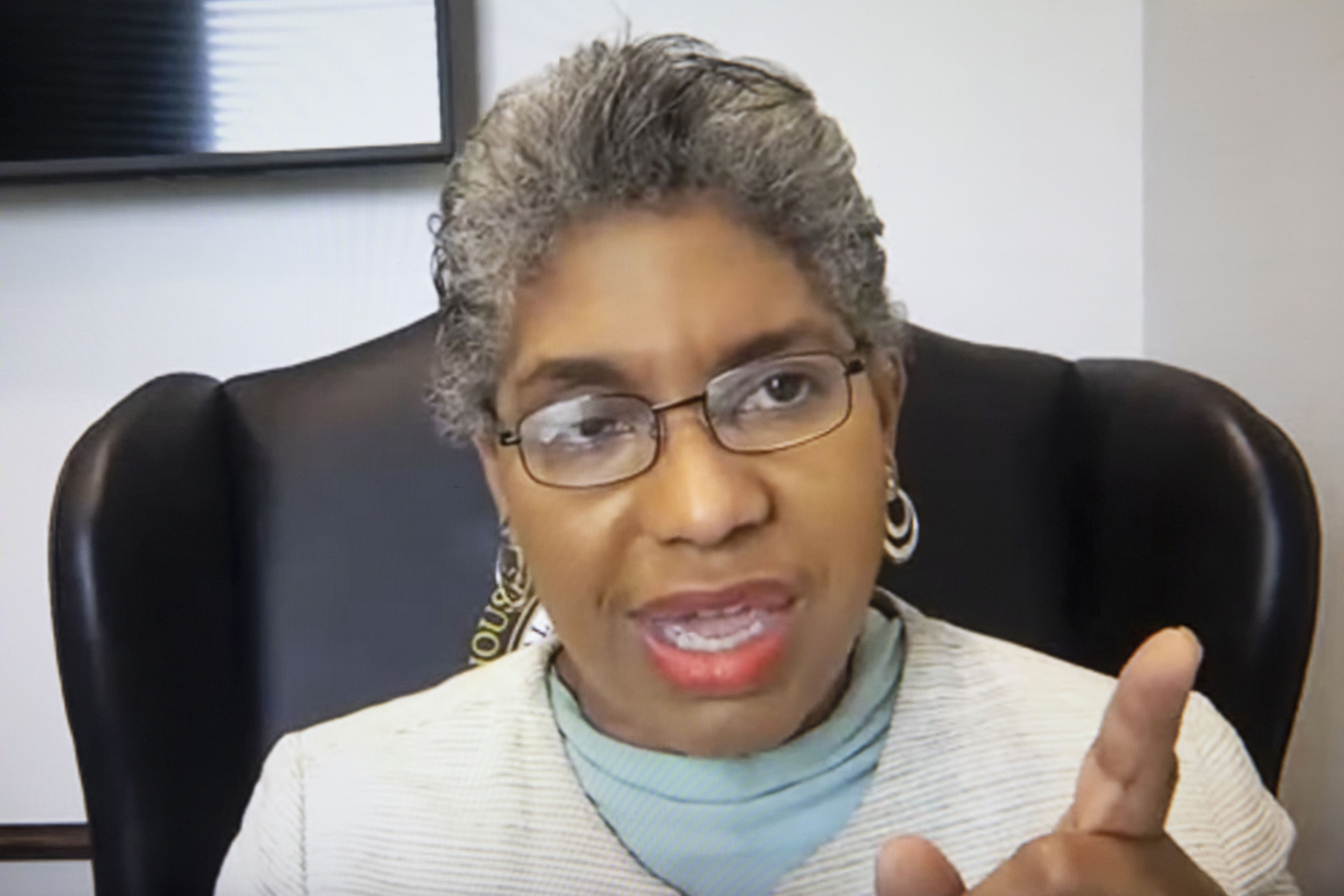

Keisha Blain, a Carr Center fellow and associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, pointed out that the massacre has never been completely documented, which explains why many modern Tulsans remain unaware of it. The local Tulsa Tribune newspaper, she said, had a longstanding reluctance to mention it at all. “On the [15th] anniversary in 1936, the Tribune decided to highlight a luncheon and a senior prom, with no mention of what happened in 1921. And Oklahoma history textbooks erased the race massacre. All the efforts that were made to hide the history need to be discussed openly.”

Moderator Sushma Raman, executive director of the Carr Center, pressed Blain about the “politics of public memory,” particularly in light of recent controversies over the teaching of critical race theory. Blain answered that commemorative gestures are not enough.

“You can talk about a lovely symbolic gesture, which we’ve seen over and over again,” Blain said. “What’s not easy to do is for a newspaper to come out and say, ‘Yes, we did intentionally not talk about it. So how about we figure out a practical step forward — which might have something to do with who we hire as journalists in this very day.’ That’s a concrete step. It will cost you something, but at least it will go beyond ‘I’m sorry.’”