Cease-fire terms during Pontiac’s War: British retreat and one Black boy

Native leader, seeking visible status symbol, bargained for an officer’s slave

Essay by Tiya Miles, Harvard professor of history, excerpted from the anthology “Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619‒2019,” edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain.

The resolution of armed conflict between British troops and a multitribal Indigenous fighting force in May 1763 depended, in part, on the ownership of one Black boy. Did the child believe his chances for staying alive and perhaps gaining freedom were greater in his current condition, as the property of a British officer? Or did he think he might fare better under the authority of the Indigenous political and military leader who sought to obtain him? Did he even know that his life was on the trading floor, as officials in the besieged fort town of Detroit negotiated a potential cease-fire in the altercation known as Pontiac’s War? Only a few words exist in the colonial archive to distinguish this child from any other in history: He was “a Negroe boy belonging to James [Kinchen]” desired as “a Valet de Chambre to Marshal Pontiac.”

Pontiac, the Ottawa-Ojibwe military strategist for whom this conflict was named, had risen as a leader of his people in the wake of the French and Indian War. This prolonged battle between Britain and France had erupted in 1754 over control of land and trade on the North American mainland. After the French scored several victories, the British finally prevailed, forcing the French into a surrender following the decisive Battle of Quebec in 1759. France and Great Britain negotiated a peace treaty in Paris that officially ended the conflict in 1763, or so those representing these imperial powers thought.

French and British negotiators had failed to include members of the multiple Indigenous nations who occupied the Saint Lawrence River Valley, Great Lakes, and Ohio River Valley lands that they had contested. The new geopolitical order hampered Native American negotiating power, increased British settler presence, weakened Native traders’ economic position, and contributed to the subsequent loss of Indigenous lands and lives. The British now controlled the region’s military forts as well as the European side of the lucrative fur trade, and they treated Native trading partners with far less respect than had the French.

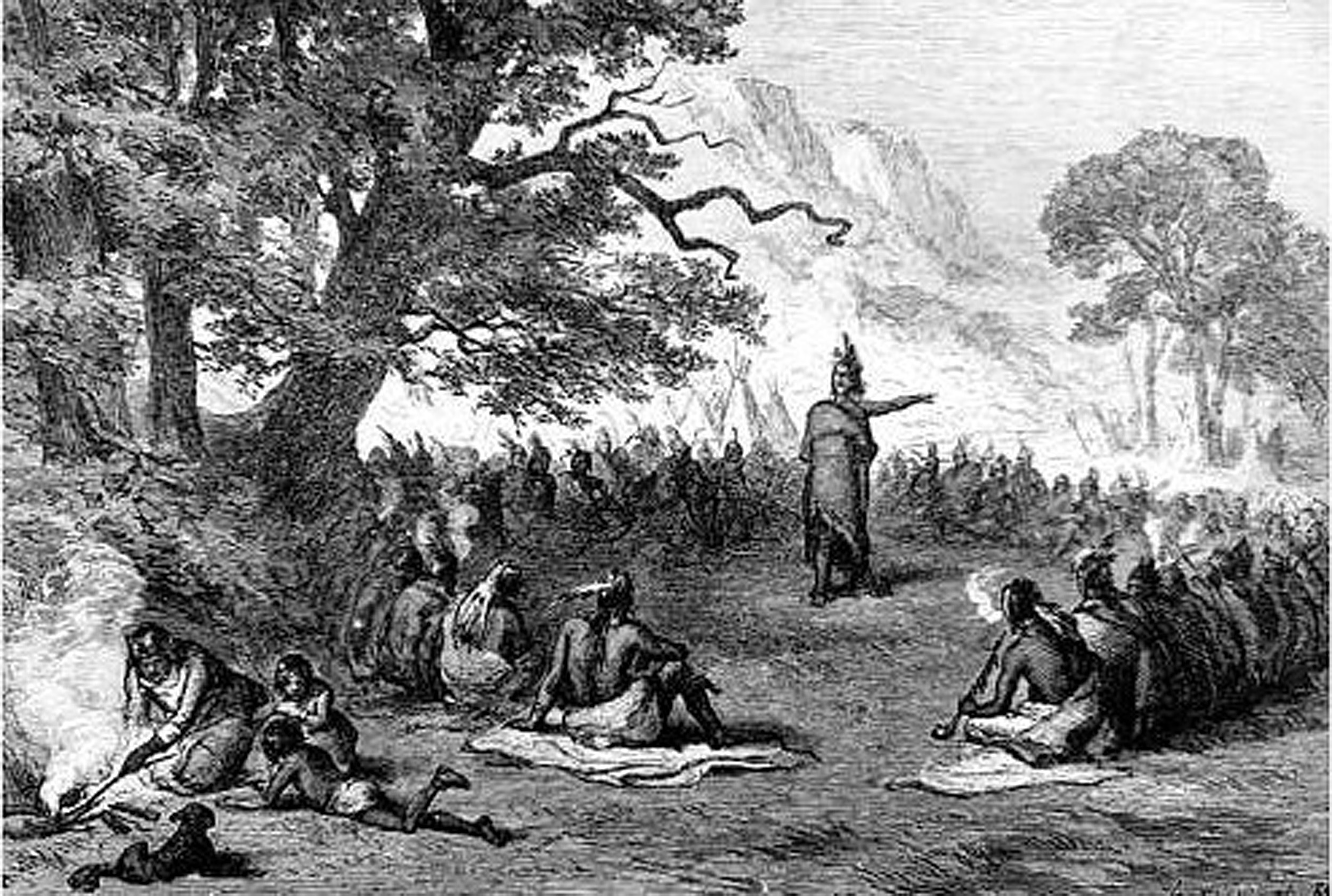

A 19th-century engraving of a famous council held on April 28, 1763, where Pontiac urged listeners to rise up against the British.

Engraving by Alfred Bobbett/Wikimedia Commons

Some Native people refused to accept this dramatic change in circumstances. Pontiac counted himself as chief among them. Critically assessing the political landscape and embracing the bellicose message of the radical Delaware prophet Neolin, Pontiac organized a coalition of Ottawa, Ojibwe, Huron, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, and Miami defenders of the land. In addition to mounting surprise attacks on and seizures of British posts throughout the region, the coordinated plot included a siege of Detroit, a prosperous town and British stronghold on the western edge of European settlement, originally founded in 1701 by the French. Just as Pontiac held Detroit by the throat, blocking the residents’ source of supplies at the Detroit River and taking two British officers captive, he stated the terms of his withdrawal. Pontiac would release Detroit if the British retreated to their original colonies east of the Allegheny Mountains and also left for Pontiac’s exclusive use a certain “Negroe boy.”

Pontiac’s demand for a British evacuation and the exchange of one Black child said much about his clear understanding of how the balance of power was being reshaped in the Great Lakes. The British had expropriated, by military force and diplomatic fictions, massive swaths of lands and had acquired, by trade as well as by natural increase, thousands of enslaved people of African descent. Pontiac sought to reverse this order by calling for the British to depart, which would restore the most recent status quo, in which the less offensive French had occupied the inland forts. At the same time, he participated in the new order by attempting to muscle his way into Black slave ownership. By taking the boy for himself, the Ottawa leader would acquire not only a captive worker but also, and just as important, a visible status symbol in the form of a personal attendant of African descent.

Black boys and young men, though rare in Detroit and the upper Midwest, were highly sought after by members of the British merchant and military elite. By owning one, Pontiac could express without words his political and military equality to his European adversaries. After this moment, and especially during the Revolutionary War era that would soon follow, the enslavement of African-descended people as a specific group of racialized others would spread across a region where Indigenous slavery had formerly been the most common means of labor exploitation.

We do not know what became of this one Black boy. But we know that the British officers refused Pontiac’s offer, and that his siege of Detroit and bold bid to oust the British failed by the autumn of 1763. The child, we can presume, remained the property of a British officer within the palisaded town of Detroit, where approximately 65 others of (usually) Indigenous American or (sometimes) African descent were held captive in the mid-1760s. As former British officers and military personnel joined the ranks of the merchants, the Black men and boys they preferred to own were put to work alongside Indigenous men and boys transporting supplies and beaver hides hundreds of miles across the Great Lakes and into upstate New York. James Sterling, a British merchant who moved to Detroit in 1761, kept records that revealed a growing transregional network of merchant elites who shared the labor of a few enslaved Black boys and men and helped one another track down and secure runaways. Early Detroit was fueled by the labor of people of color twice contained, by the walls of the town and by a series of agreements between French, British, and later American leaders permitting slavery’s continuation.

Tiya Miles is a professor of history at Harvard University and the Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The place that would eventually become the capital of the Michigan Territory grew practiced at confining and surveilling unfree people, ensuring the regular theft of their labor for economic, political, and symbolic ends. A century later the state of Michigan would perfect this practice of extractive entrapment. In 1838 the Michigan state legislature approved construction of the first state prison in Jackson. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, Michigan had formally abolished racial slavery just one year prior, with the ratification of its new state constitution in 1837. By 1843, prisoners were working for private contractors to produce farm equipment, textiles, tools, saddles, steam engines, barrels, and more at no pay. Michigan expanded the facility until in 1882 the castle-like fortress was said to be the largest walled prison in the world. The state assigned inmates to mine coal on public lands and soon had farming activities and factories operating on 65 enclosed acres.

Michigan is still home to one of the most extreme human containment systems in the United States. Its prison population has increased by 450 percent since 1973, and the state maintains a higher rate of imprisonment than most countries. African Americans are the largest incarcerated group by far in Michigan, with a total population of 14 percent and a penal population of 49 percent. Latinos and Native Americans are incarcerated in Michigan at rates equal to their population percentage. However, white Michiganders, who make up 77 percent of the general population, are underrepresented in the prison population at 46 percent. Racialized sentencing policies have much to do with these statistics. Historians Heather Ann Thompson and Matthew Lassiter, the founding codirectors of the Carceral State Project at the University of Michigan, point to “draconian” state legislation that by the 1990s included the infamous “lifer laws,” which exacted life terms for narcotics possessions of over 650 grams and extinguished the opportunity for parole. As men and women were thrown behind bars for nonviolent offenses in the 1980s through the early 2000s, Detroit neighborhoods were gutted, children were orphaned, and voter rolls were depleted. And just as this Black prison population skyrocketed at the end of the twentieth century, the state loosened legislation to allow for an expansion of convict labor.

In the modern mass incarceration moment, the racialized “carceral landscape” of Colonial Great Lakes slavery found an echo. The story of one Black boy foreshadowed the fate of too many Black prisoners.

“One Black Boy: The Great Lakes and the Midwest” by Tiya Miles. Copyright © 2021 by Tiya Miles. Excerpted from “Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619‒2019” edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. Published by permission of One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.