AP file photos; photo illustration by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard Staff

The legacy of the 2010s

Harvard experts reflect on some of the most important moments and cultural trends

Adiós, 2010s. The 2020s are here. But before the clock strikes midnight on the decade, the Gazette asked Harvard experts to weigh in on the biggest events and most important cultural shifts of the past 10 years.

The rise of the smartphone and streaming services

As the Martin Marshall Professor of Business Administration and co-chair of the HBS Digital Initiative at Harvard Business School, Greenstein studies all things tech.

The smartphone has led to a massive reallocation of leisure time, and the source of many functions. For most professionals it has blurred the boundary between work and leisure, at the expense of work for many. It changed ticketing; it enabled ride-sharing; mapping and real-time navigation have moved to apps. Gaming, too, went through a huge change and so did social networking. Photography and movies also changed with smartphones, and payments and finance are going through a transition right now — it has already happened in China. This is also bringing about a massive change in the developing world, where the smartphone serves as the channel for diffusing banking, credit, payments, communication, social networking, news (fake and otherwise), and on and on.

As for streaming — most people do not recognize that the streaming movement started with YouTube and its competitors, such as Vimeo. That goes way back to 2005 and as technology, compression, formatting, and rendering got better, insiders could see that long-form video was coming — and it did. Without question Netflix led the charge this decade in streaming, but now there are so many streaming services, I have lost count. Disney Plus recently passed 10 million subscribers in its first week, and that tells you that streaming has gone as mainstream as, well, Mickey Mouse. This has significance because it is now possible to watch just about any television event through the internet. For many people, that is enough to motivate them to consider not subscribing to cable TV – i.e., to become a “cord cutter.” This is interesting because a few years ago most cord cutting was about income. Cable subscriptions were expensive, and low-income households simply did not want to pay. Now it is more about preference as more content comes online — though cord cutting is still far from becoming truly mainstream.

More like this

Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Sunrise Mobilization, and #MeToo

Ganz, the Rita E. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at the Harvard Kennedy School, teaches, researches, and writes on leadership, organization, and strategy in social movements, civic associations, and politics.

More like this

In 2011, you have Occupy Wall Street, which didn’t result in huge institutional changes but did produce a radical shift in public discourse about wealth inequality. In 2014 Michael Brown’s murder sparked Black Lives Matter, and that has had an enormous impact in many different ways. For example, the illusion that, somehow, we were past racism as a problem has surely been shattered, and that’s a good thing. In reaction to Trump’s election, the Women’s March, followed by the #MeToo Movement, sparked a gender-based mobilization that continues to reverberate. In 2017, there was March for Our Lives, which resulted from the tragic Parkland murders, and that one cut through on a generational level like we haven’t seen before, followed today with the Sunrise Mobilization on climate change.

So it’s been a decade of looking at core challenges in American political culture that have to do with race, economic inequality, gender, immigration, the environment, and more. The motivations for these types of movements were out there this decade, and the challenges for everyone involved in these movements now is how do they translate this mobilization to the organization needed to wield the kind of power at the ballet box, economically, and culturally to achieve the changes these movements are calling for? It is an incredibly exciting and important time. An old friend, the activist Tom Hayden — who passed away in 2016 — used to say “change is slow except when it’s fast,” and we’re in a fast moment right now, and it’s, sort of, up for grabs whether this is going to be a moment that enhances the humanistic core of our values or it goes in the opposite direction. I think that’s where we are right now at the close of the decade going into a new one.

Mass shootings and gun control

Professor of health policy at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center; author of the 2006 book “Private Guns, Public Health.”

The big thing that these showed to the entire U.S. is that everybody is at risk. It showed suburban moms that their kids are at risk. It showed that anyone could get killed at any place, so suddenly instead of being about “them” it is about “us” as a society.

It is common for mass shootings to receive the most media attention and to have an effect, even though they represent only a tip of the iceberg of all of the problems relating to guns. Mass shootings this decade have revitalized the notion that gun violence is a huge public health problem and that we can do something about it.

The past few years have seen an increase in the number of gun homicides and gun suicides, and nobody quite knows why. But, with that, during this past decade the interest of everyone trying to find solutions or starting to do things about it has increased. For example, for the first time ever we have three states — Washington, New Jersey, and California — that are funding gun research. We have a new news outlet —The Trace — which just features stories about guns. We have politicians talking about gun violence prevention and running on it. Many companies are standing up to the gun lobby, including Walmart, L.L. Bean, and Dick’s Sporting Goods. And there has been a huge awakening of scholars who want to do gun research. It looks like this will continue in the coming decade, as well.

Superheroes assembled

Senior lecturer in ethics and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and director of pedagogical innovation at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. As part of his work, Robichaud looks at issues in moral and political philosophy in pop culture, especially superhero narratives.

At the end of the 2000s, we got these two amazing superhero movies: “The Dark Knight” and “Iron Man,” which each gave a real promise of what these movies could offer going forward. “The Dark Knight,” a crime saga, showed you don’t have to tell a traditional superhero story — you could tell a different genre story with superheroes — and “Iron Man” set the foundation for a cinematic universe — like the one we’ve seen in the comic books — where we tell individual stories and then bring it all together for signature, tentpole events.

What we had this decade, in my opinion, was superhero narratives following those two trajectories. We had movies that have recognized that you can tell really compelling stories with superheroes that don’t fall into the trap of being a typical superhero story — like Westerns, heist stories, high school comedies, space operas, spy thrillers that featured superheroes — and even TV shows like HBO’s “Watchmen,” which was a story about race and policing with superheroes.

This decade, we also saw Marvel deliver its cinematic universe, and even though “Avengers: Endgame” is the freshest thing in our heads, we can’t ignore what an amazing event “The Avengers” was at the start of the decade in 2012, which brought all these characters together that we had already known in their own movies into one. Had that failed we would have never gotten this cinematic universe or a decades-long story arc that concluded with “Endgame.”

That said, going forward, I feel we are in a similar place with superhero movies now, where we are seeing the promise of what’s coming this next decade. That promise has a lot to do with diversity and representation in superhero movies, and we got a taste of this with some exceptional movies toward the end of the decade. “Black Panther,” “Wonder Woman,” and “Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse” stand out the most. I hope that we look back at these movies at the end of the next decade and say these got something started that we’ve seen a ton more of, and it’s really, really awesome.

More powerful computers and Big Data

Executive director of the Institute for Applied Computational Science and assistant dean for professional programs at the Harvard Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Who would have thought the last decade would usher in the benefits of vastly improved voice-recognition systems with our friends Siri and Alexa, automatically updated traffic maps from Waze, autonomous vehicle advances, and sharing-economy companies like Uber and AirBnB, along with the challenges of surveillance, facial-recognition systems, election influencing, and the specter of economic dislocation, all because of data-driven automation?

All these advances, and many more, have been driven by rapid increases in computational power, storage, and analytical ability, along with the development of deep learning, including neural networks, that has revolutionized our ability to solve longstanding computational problems. And as the algorithms and the fuel for them — data — begins to be deployed in many fields, like finance advertising, medicine, insurance, pharmaceuticals, and even agriculture and filmmaking, we are all — scientists and average citizens, too — contributing to advancing artificial intelligence by our rapid adoption of time-saving conveniences and the data that we generate.

In the academic world, the effect of this computational revolution has meant pressure to keep up with the advances in the field, and there is enormous demand for educational content and new curricula — in undergraduate and graduate curricula — and also in professional schools like business and law schools. Within the last decade, universities, including Harvard, have launched new programs, established initiatives in computational fields, and increased outreach to industry and research organizations. For research, new computing tools and algorithms have brought huge new approaches to answering more questions and solving longstanding problems like mapping the universe, predicting earthquakes, and developing chemical compounds. Researchers around Harvard and the world are exploring some of the most exciting questions using these new tools being developed in artificial intelligence.

‘Hamilton’ and a broader vision of diversity

William Powell Mason Professor of Music; author of “Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War” (2014). Her current project, “Black Virtuosos and Civil Rights,” aims for a cultural history of a generation of African American performing artists breaking through in classical music.

More like this

“Hamilton” embodied the hope of the Obama era with a capacious vision of humanity. It was brilliantly virtuosic, brimming with good humor, focused on community-building, and dedicated to celebrating the diversity of America. The Tony- and Pulitzer Prize-winning musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda opened on Broadway in January 2015, but its germination stretched back at least to 2009, when Miranda performed a song from what was then “The Hamilton Mixtape” at a White House Evening of Poetry, Music, and the Spoken Word. Just imagine: music and poetry at the White House, created by a Latinx performer! The show disrupts standard founding-father narratives, with their litany of all-white heroes, and instead casts people of color as the country’s progenitors. Alexander Hamilton raps his vision of democracy with frenetic intensity. Aaron Burr croons R&B ballads. Thomas Jefferson jives. In the process, immigrants and the legacy of slavery move to the center. “Hamilton” continues to pack the Richard Rodgers Theatre on West 46th Street, with spin-off productions on the West End, in Chicago, and on tour, with Hamburg and Sydney in the future.

Why was “Hamilton” one of the biggest cultural phenomena of the 2010s? Perhaps most fundamentally, it represents excellence. In the annals of Broadway, “Hamilton” is destined to join a core group of musicals, including “West Side Story,” that are remembered for addressing profound contemporaneous issues while delivering accessible entertainment.

National legalization of same-sex marriage

Kirkland & Ellis Professor at Harvard Law School and the author of “From the Closet to the Altar: Courts, Backlash, and the Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage” (2013).

Obergefell v. Hodges [the same-sex marriage case decided by the Supreme Court on June 26, 2015] has been called the Brown v. Board of Education of the gay rights movement. Like Brown, Obergefell came at a time when national opinion was deeply divided on the underlying issue, and it will come increasingly over time to seem obviously right and just, as public opinion continues to move in support of gay marriage. More than 60 percent of Americans approve of gay marriage, with support growing at a rate of roughly 2 percentage points a year. What’s more, one of the current candidates for the Democratic nomination for president is very openly a gay, married man — Mayor Pete Buttigieg.

Equally important, unlike with Brown, Obergefell failed to produce a wave of massive resistance. To be sure, a county clerk in eastern Kentucky briefly went to jail rather than grant marriage licenses to gay couples, and a state Supreme Court justice in Alabama shouted defiance at the Supreme Court’s ruling (much as an Alabama governor had shouted defiance of Brown more than 50 years earlier). But almost everywhere else in the U.S., the court’s ruling was peacefully implemented. The sky did not fall, and gay and lesbian couples began to enjoy a basic human right that had long been wrongfully denied to them.

Self-destructing Banksy painting and critique of commercialism

Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums. Her scholarly interests focus on 20th- and 21st-century global art.

More like this

Banksy’s work was at auction. It sold for $1.4 million, and then it basically destroyed itself. To understand the significance of this, it’s helpful to know what his practice is about. He’s a graffiti artist, and speaking very generally, by definition, his work is meant to be outside on walls of buildings, or sides of bridges, in short, done secretively; graffiti as a visual statement is meant to be about breaking rules. It is often a means of protest and of pushing back. Banksy is both an extraordinary painter and artist, and his graffiti typically presents extremely clever, hyper-real, recognizable images of people in unexpected and noticeable settings, where his images critique whatever is known to happen in that setting — whether it is the machinations of Wall Street or the Church. In some ways, people have looked at his work and thought his images were such that they could be on a canvas hanging in a museum or in someone’s living room because they are so beautifully painted. But Banksy has pushed back on that system, and his identity remained hidden.

So starting from that point of the anonymous artist whose work is accessible to all on the street, then he reaches a point where he decides to sell his work on a canvas to wealthy collectors, raising the questions: What? How can that be? That’s not who he is. Banksy has always critiqued the ideas of the market and that art would even be part of a market. So when the self-destruction happened, it was ultimately not surprising. The reason this was so significant in the art world this decade, on many levels, is because Banksy very pointedly made clear the excess and the ways in which the art market has reached a point that is so extreme, so absurd, and, frankly, dangerous, and he did it in such a spectacular setting, theatrical manner, and brilliantly witty way that was truly priceless.

Twitch and the rise of e-sports

By Robert F. Higgins ’68, M.B.A. ’70

Managing partner at Causeway Media Partners, which invests in e-sports technology, and a former senior lecturer at Harvard Business School.

What was once seen as a niche outlet for only the most dedicated of gamers, e-sports developed into a global phenomenon this decade, [cracking $1 billion in 2019 and reaching 454 million occasional and frequent viewers. That’s up from 134 million in 2012.] At the center of this evolution is Twitch, the live-streaming video service, which launched in 2011 and developed into the central hub for all things gaming. From casual gamers looking to share game-play recordings with a few friends to full-time professionals making millions of dollars a year, Twitch changed the way gaming content is created and consumed online. First and foremost, Twitch contributed to the social aspects of gaming. Twitch created a community of like-minded individuals to connect and share game-play, and this socialization helped propel the formation of more organized structures in gaming, such as leagues and teams, that helped the e-sports industry take off.

But Twitch’s impact on the gaming ecosystem extends far beyond just a social network for gamers. By creating a platform where content could be consumed and created with minimal barriers to entry, individuals who were either particularly skilled at a certain game and/or entertaining on camera began to amass large followings. Suddenly, anyone with a laptop, a camera, and a lot of free time could reach millions around the globe, and because consumers quickly turned to Twitch to watch their favorite gamers perform, streamers gained notoriety and thus influence. Their opinions became extremely valuable and eventually highly lucrative to game developers and companies looking to promote their products through digital means.

Crucial to appreciating Twitch’s impact on e-sports is understanding the power dynamics that exist within the broader gaming ecosystem. It used to be the case that game developers held all the power of what games fans were going to buy. With the introduction of highly visible streamers, game companies were forced to listen to their consumers’ opinions. Fans were no longer just fans. Video game players evolved into hugely sought-after influencers getting paid handsomely not only to play a certain game but also to have opinions on that game. As a result, Twitch has come to play a huge role in determining which games are successful both recreationally and professionally.

2016 presidential election and youth engagement

Director of polling at the Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics, where he has led polling initiatives on understanding American youth since 2000.

The aftermath of the 2016 election served as a once-in-a-generation reckoning regarding the tangible difference politics can make, especially among young voters. Unlike any time since pre- and post-Sept. 11, Harvard Institute of Politics polling tracked double-digit changes in public opinion among young Americans regarding the efficacy of political engagement. In 2017, we saw a 15-point swing in public opinion toward a recognition that politics mattered. Whichever side of the fence you were on before, it was clear in the Trump era that politics mattered. It was this attitudinal shift, along with the efforts of organizers and activists, that resulted in historically high levels of turnout and participation among America’s youth in the 2018 midterms. And according to 2019 IOP polling, there are no signs that voter enthusiasm and engagement will wane anytime soon.

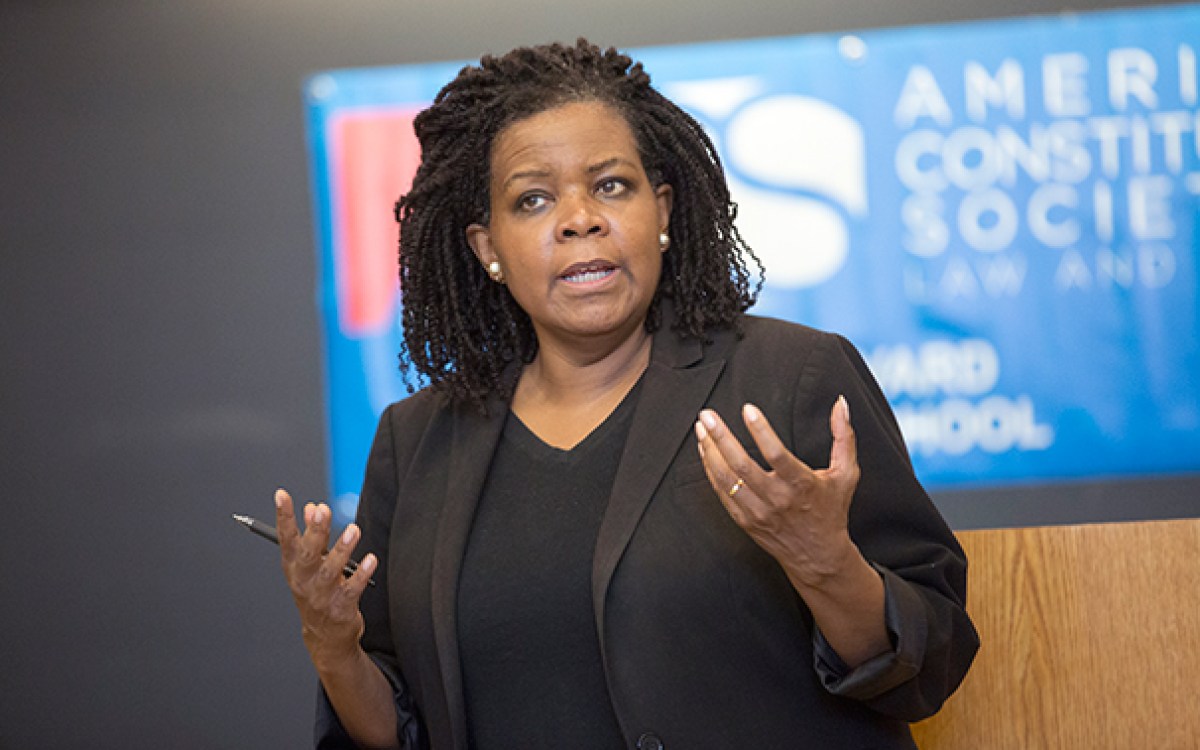

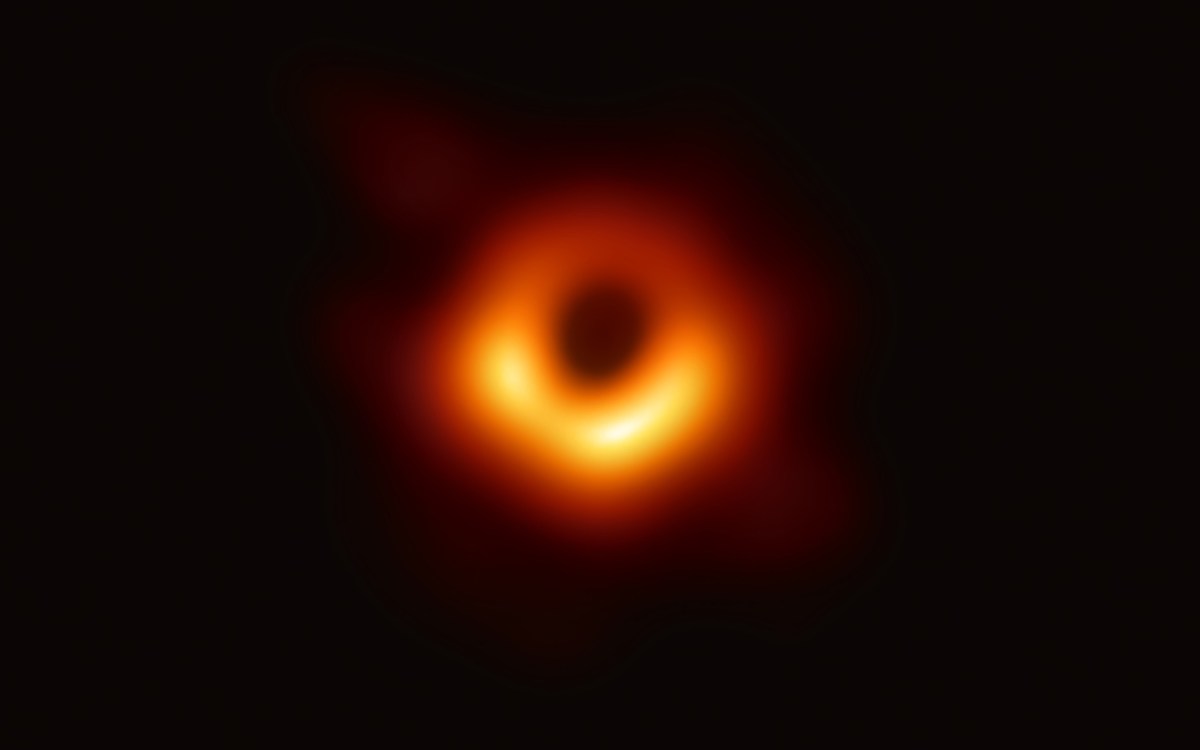

The black hole image

SAO radio astronomer, Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. Blackburn led efforts to reduce and calibrate data from the Event Horizon Telescope, which captured the image of the black hole.

On April 10, 2019, a global team of 348 astronomers, including leading members from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, unveiled the first-ever image of a black hole taken by the Event Horizon Telescope. Black holes, as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, are some of the most mysterious objects in the universe — just the idea that they might exist has captivated scientists and the public for a century. Billions of people saw the first image, which provides foundational support for Einstein’s fundamental theory, and it appeared on the front pages of most major newspapers around the world. Taking a picture of a black hole required simultaneously connecting eight radio telescopes across the world to form a virtual telescope the size of the Earth. This was made possible through the collaboration of hundreds of scientists at more than 60 institutions in 20 countries who worked together to make the observations, and process and interpret the data in a truly global scientific effort.

The interviews were edited for length and clarity.