Since millions took to the streets across the U.S. for the Women’s March in January, women have begun speaking out about their experiences as victims of sexual harassment or abuse in what’s become known as the #MeToo Movement.

Photo by Ronen Tivony/NurPhoto

The women’s revolt: Why now, and where to

The #MeToo surge against sexual abuse provides opportunities for pivotal societal change, but challenges too

When allegations of serial sexual misconduct by movie mogul Harvey Weinstein broke in October, they triggered a cascading national reckoning over sexual harassment and assault in the workplace and beyond. In the weeks since, women have leveled charges against many high-profile men in entertainment and media, business and politics. As the accusations continue to erupt through the burgeoning #MeToo social media movement, many observers are wondering if the nation is finally beginning to deal with gender inequity.

Recognizing inappropriate behavior as harassment was a radical concept in 1979, when activist and attorney Catharine MacKinnon published “Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination,” a groundbreaking book that tackled sexual discrimination in the workplace head-on. Seven years later, MacKinnon was co-counsel in the U.S. Supreme Court case that recognized such harassment as a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Today the James Barr Ames Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School tells the Gazette she is “inspired by the brilliance, heart, and grit of all the survivors who are speaking out and reflecting on their experiences of sexual violation, and being listened to.” And she said the downfall of so many powerful men is stunning, “especially given decades of stonewalling and recalcitrance and siding with abusers.”

To gauge the sweep of the emerging movement, the Gazette in recent days interviewed University scholars across a range of disciplines, asking them to assess the repercussions and reactions that are redefining the sexual landscape and to explain how society might change in the process. Here are their thoughts on some key aspects.

The power of narrative in the post-Weinstein era

Why did the Weinstein story open the floodgates to a movement when similar revelations about comedian Bill Cosby, Fox News chief Roger Ailes, and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump did not?

Ann Marie Lipinski, curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, said she suspects the response is a combination of women simply having “had enough,” along with the celebrity of many of Weinstein’s accusers, including actors Ashley Judd, Rose McGowan, and Angelina Jolie. Their status drew widespread attention to the issue, but it’s a “frustrating fact” that famous women were deemed more credible and were more readily heard than the mostly unknown accusers of Cosby or Trump, Lipinski said.

“For all those women working night shifts in hospitals or stocking things in grocery stores or working in a lot of industries where there is more anonymity and not the same level of public scrutiny or, in many cases, fame, it must be pretty frustrating to feel that your complaints are not being taken with similar seriousness,” she said.

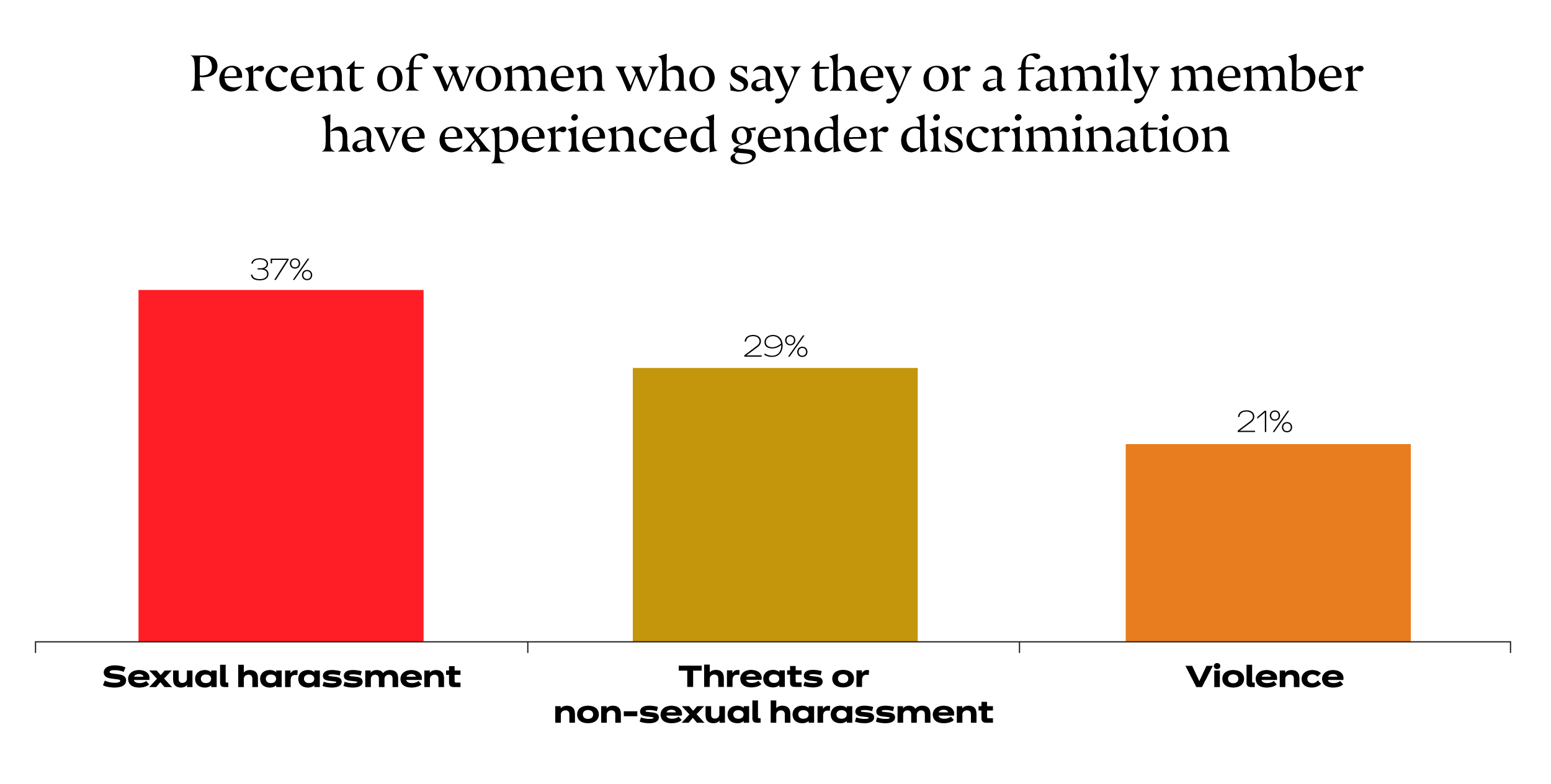

Source: NPR/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of American Women.” This survey was conducted Jan. 26–April 9, prior to the country’s widespread discussions in the fall regarding sexual assault and harassment. These national conversations may have affected how people viewed or responded to their own experiences, or their willingness to disclose these experiences in a survey.

Graphic by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard staff

Anyone’s personal story can prove a powerful tool for change. The #MeToo movement has inspired countless women, and some men, to share their experiences with sexual assault or harassment.

Historian Tim McCarthy isn’t surprised at the outpouring. Narrative has been a unifying and mobilizing force through history, said the director of Culture Change & Social Justice Initiatives at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS).

In the first half of the 19th century, slave narratives — stories that bore witness to the brutality committed against people treated as property — “were incredibly powerful in terms of moving public opinion of a culture that was increasingly literate and increasingly divided” over abolition, said McCarthy, who lectures on history, literature, education, and public policy. Similarly, the violent images that filled newspapers and American TV screens during the Civil Rights Movement a century later brought entrenched racism into vivid, visceral relief for audiences outside of the South, he said.

In recent decades, the stories of gay men and women eager for the same rights and protections afforded heterosexuals have helped advance the LGBTQ movement and the recognition of same-sex marriage.

“All of these movement moments that changed hearts and minds and moved a nation in the direction of justice have been rooted in storytelling,” McCarthy said.

Narrative has been a powerful agent of change throughout history, says Tim McCarthy.

Harvard file photo

Centuries of untold stories

For centuries, women have struggled with sexual harassment and abuse at work and at home. But often they have had to forgo battling against it or telling their stories to make other gains, said Phyllis Thompson, a cultural historian and lecturer on studies of women, gender, and sexuality.

In the 1800s, suffragists were reluctant to talk about sex crimes of all kinds, in part because the topic was considered “indelicate.” In addition, “to have a discussion of sex crimes in the workplace requires that one have an understanding that all genders legitimately belong in the workplace, and that was just simply not the case in the 19th century. There was no sense of a right for women to have workplace treatment on a par with men,” Thompson said.

In the end, Thompson said, even suffragists like Lucy Stone, who complained of “crimes against women,” dropped the divisive issue so they could focus on establishing a right-to-vote platform that would have “mass buy-in.”

Second-wave feminists concentrated on securing equal pay for equal work and on access to jobs typically reserved for men. “There was so much initial focus on making sure issues of access to work were resolved, it took a while before people started having the wherewithal to tear apart routine sexist practices within the workplace,” said Thompson, who teaches the College course “The History of Feminism: Narratives of Gender, Race and Rights.”

The second-wave feminists opposed sexual assault at home and on the job and helped push through an amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibited gender discrimination in the workplace.

Pivotal texts on sexual misogyny, such as Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 “Against Our Will,” moved the topic of sexual assault and rape further into the national discourse. “[Brownmiller’s] argument, that the threat of sexual abuse is a tool of domination, was important for this moment,” said Thompson. “It was a crucial piece of theoretical thinking for the second wave.”

Phyllis Thompson finds hope in the #MeToo movement’s ethos of solidarity.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

As to the current moment and the countless stories of harassment being told online and in person, Thompson said she hopes they will produce lasting change, but she worries about diversity. “Insofar as what some call third-wave feminism has been broadly critiqued for the individualism of its politics (‘To each her own feminism’), the #MeToo moment is a kind of corrective in that its presumptive ethos is one of solidarity,” she said. “But, unless feminists (and the media, and the national audience) start doing a better job of highlighting and listening to the voices of people who have been doubly marginalized, such as women of color and those of lower socioeconomic status, there will be important limits on what can be accomplished.”

“The movement for women’s equality that we need — and that I believe would have long-term traction — is one in which the dignity and rights of all human beings are honored, one that insists on an anti-racist politics, and that doesn’t tolerate structural sexism.”

Phyllis Thompson

Men need to take greater responsibility for creating a more equitable culture and for helping move the conversation well beyond heterosexual harassment and assault to include broader, fundamental reform of institutions, education, and justice, said Thompson.

“The movement for women’s equality that we need — and that I believe would have long-term traction — is one in which the dignity and rights of all human beings are honored, one that insists on an anti-racist politics, and that doesn’t tolerate structural sexism,” she said.

The power of culture in a culture of power

Despite differences of degree and detail in their behavior, at the heart of the accusations against well-known men — from television host Charlie Rose and actor Kevin Spacey to rap mogul Russell Simmons and star chef Mario Batali — is an abuse of power, analysts say.

“What gives men any sense that they have permission to do this? It’s hard for me to conclude that it’s anything different [than] just a basic disrespect and disregard for women and their boundaries,” said Robin Ely, the Diane Doerge Wilson Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School (HBS). With that broader cultural message often a norm, it’s not surprising that workplaces become infected by such attitudes, since men call most of the shots at work.

The recently accused men all have tremendous authority in their fields, and the ability to use their star power to coerce less-powerful women and men into harmful situations and later to push them toward silence. So is a corporate executive likelier to sexually harass than a bus driver is? Though that’s not entirely clear, there’s ample research in social psychology to suggest that power has wide-ranging corrosive effects on both cognition and behavior.

Robin Ely studies gender relations and power dynamics within organizations.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Studies of power dynamics show that high-powered people are more likely to take risks, to focus on rewards while ignoring possible failures, and to be overconfident in not only the likelihood of success, but in their own judgments, opinions, and skills. Power leads people to be more optimistic about outcomes and to believe that they can exert greater control over outcomes than they actually can.

Research also says that people in power are more likely to cheat and lie, are better at it, and are more likely to objectify others. Having power directs a person’s attention away from the interests of others and allows them to focus on themselves. In addition, the powerful generally have far greater financial and legal resources to protect themselves from reprisals for their bad behavior.

“What gives men any sense that they have permission to do this? It’s hard for me to conclude that it’s anything different [than] just a basic disrespect and disregard for women and their boundaries.”

Robin Ely

Francesca Gino, the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration at HBS, studies why dishonesty and other unethical behavior persists in organizations. She has found that people who are serially dishonest often behave unethically, feeling little or no guilt when they can convince themselves that what they’re doing isn’t immoral.

“For years, I’ve explored the gap between people’s actual dishonest behavior and their desire to maintain a positive moral self-image. To explain this apparent gap, my research illustrates how even subtle forces divert us from our ‘moral selves’ … and that even good people often engage in behavior that violates their own ethical goals,” Gino said in an email exchange.

Gino’s work suggests that creative and innovative people are more likely to be “morally flexible” because they can create rationales that shift how they view and justify unethical actions. In a series of experiments involving advertising agency workers, Gino’s team found that a creative mindset was a better predictor of dishonesty than intelligence. In addition, people who act unethically often rationalize their behavior afterwards — or forget it entirely — and so are more likely to repeat it.

“This work helps explain why unethical behavior is so pervasive in organizations and in society more broadly,” she said.

The different ways that men and women tend to handle power may account for why so many male industry titans have been accused, and almost no women leaders so far. Gino’s work shows that men tend to unconsciously associate sex and power more readily and frequently than women do, and that men who link the two are more likely to use coercion to get sex, she said. One study found that such men are also more likely to say they would sexually harass a woman in a hypothetical workplace. Other research found that powerful men often inaccurately convince themselves that others are more sexually interested in them than they are, prompting them to act out.

But high-status men are not always the bad guys. When insecure, low-status men suddenly acquire power, such as in the tech world, they are more likely to take advantage of that newfound power and be sexually aggressive than high-status men are, according to a new study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Francesca Gino says her research shows that men tend to unconsciously associate sex and power more frequently than women do.

Harvard file photo

HBS’ Ely, who studies gender relations and power dynamics within organizations, says that for women of her era, sexual misconduct in the workplace was an ugly fact of life with no clear remedy.

“We entered the workforce long before sexual harassment was very well understood. I know for myself, with the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas hearings, that’s when I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, yes, I’ve been sexually harassed.’ I’d never really thought about it that way; it was just kind of an annoyance. But then I became more aware of it.”

Companies traditionally act slowly, if at all, on sexual harassment and misconduct charges, so Eugene Soltes, the Jakurski Family Associate Professor of Business Administration at HBS, said he has been surprised at how quickly firms such as Amazon Studios and NBC have removed top executives or franchise talent like Matt Lauer, the former “Today Show” host.

Some businesses deserve credit for decisive responses that can minimize the reputational harm such cases can inflict, Soltes said. But many others often contribute to unwanted sexual behavior in the workplace either by protecting accusers with settlements or by failing to take basic early steps against misconduct before it becomes untenable.

Employees caught embezzling or committing other financial crimes typically face swift prosecution or lawsuits from employers or investors, which leaves a civil or criminal paper trail for future employers, said Soltes, who studies white-collar crime. But with sexual misconduct, the circumstances surrounding an employee’s termination often remain shrouded in secrecy long after the accused has moved on. Cases are often settled in-house or in arbitration, where there is no obligation of public disclosure, and parties often sign binding nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) that mean neither the accuser nor the accused can discuss what happened. Although companies could reveal that former employees were let go for sexual misconduct during a reference check by other firms, Soltes says they rarely do.

“There’s no explicit law that would prevent Employer A from telling Employer B ‘The reason we fired this person is there were three allegations of misconduct against him.’ But that would set them up for potential defamation suits [or] some potential [legal] issue,” said Soltes. “So what do firms do? They say ‘We can’t comment.’ That’s something that allows serial perpetrators to effectively move around, which you don’t see with other kinds of misconduct.”

Soltes said that while recent media coverage has focused on the fall of powerful and high-profile figures, sexual misconduct at lower levels of the workplace is widespread.

“It’s not explained by one or two executives at each firm. That doesn’t make sense” given data showing that a majority of women report that they have experienced some form of sexual assault, harassment, or other sexual misconduct, he said. Everyday comments, gestures, or looks from colleagues are a “gray area” of mistreatment that falls short of a crime but is nevertheless unwanted and is, over time, corrosive.

“It’s amazing to see how men get this notion of consent: ‘If no one says it’s wrong, it means someone is consenting to it.’ That seems to be what’s happened,” said Soltes.

“It’s going to be a difficult next phase for many men, recognizing that you’re not necessarily Harvey Weinstein or some of these people doing truly, truly egregious things [but you are still making women uncomfortable],” he said. “I think, frankly, many of the men engaging in that behavior are probably overall reasonable, well-intentioned individuals who just simply don’t see the consequences of their actions, and things that they might think are compliments are actually not interpreted that way.”

“I’m impatient for fundamental change … a more equitable management division [between men and women], and cultural changes,” says Ann Marie Lipinski.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Journalism has played central roles, good and bad, in the public reckoning that has followed the Weinstein exposé. The media has been the vehicle by which investigations into longtime rumors, reports of accusations or secret settlements, and first-person testimonials were made public. But journalists have been also prominent among those accused.

A-list show hosts, reporters, editors, and executives at marquee news outlets have been fired over allegations of sexual behavior ranging from boorish to assaultive. Michael Oreskes, National Public Radio’s senior president of news; Mark Halperin, an NBC political pundit and author; and Ryan Lizza, a New Yorker reporter and CNN analyst, have been let go. The behavior and reaction to it appears partly an offshoot of the profession’s longstanding culture of “ritualistic hazing” and “tough love,” said the Nieman Foundation’s Lipinski, former editor of the Chicago Tribune.

“You come into a newsroom and you’re young and inexperienced … you’re thrown out on an assignment, you’re put into a situation you may not have dealt with before, and you’re at the mercy of more-skilled editors and higher-ups” for both guidance and future assignments, she said.

Long term, news outlets ought to make gender discrimination and sexual misconduct a more integral part of their everyday coverage, rather than focusing on these issues episodically, Lipinski suggested. They also should hire and elevate more women to power, and end the use of confidential arbitration agreements in TV news employment contracts.

“I’m not impatient for the quick fixes,” she said. “I’m impatient for fundamental change … a more equitable management division [between men and women], and cultural changes. That is going to take a little time, and anyone who thinks there’s a pill we can give everybody to fix this overnight is being naïve.”

Cultural historian Thompson said she would like to see the energy of change focus on “something we haven’t tried yet”: ensuring that women are proportionally represented in positions of authority across society.

“But in the meantime, if you wonder whether this thing you’re about to say or do may be offensive: a) maybe don’t do it, and b) ask a colleague,” Lipinski suggested. “Have an open conversation. In newsrooms, asking questions is a really tried-and-true and highly respected form of engagement … In some ways, we can make this more complicated than it is. I think we know what to do. I don’t think people are that confused.”

Many abuse cases display a similar power dynamic in how men respond to their accusers, a pattern defined by Jennifer Freyd, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon who studies the impact of interpersonal violence and institutional betrayal on mental and physical health, behavior, and society. Freyd developed the term DARVO, which stands for “Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender.”

That scenario has played out in courtrooms and boardrooms for decades, as attorneys and executives have repeatedly turned to a “nuts and sluts” defense to cast doubt on accusers, said Diane Rosenfeld, a lecturer at Harvard Law School whose courses include “Gender Violence, Law and Social Justice.”

“When you take a higher view of everything that’s going on, a meta-analysis, you can see that that is absolutely the way that defense works. Anytime somebody comes forward, there’s an attempt to discredit her,” said Rosenfeld. “If you look back to the Anita Hill case and her accusations against Clarence Thomas, the attorneys defending Thomas were absolutely employing the ‘she’s a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty’ tactic to break down Hill’s claims.

“I am really hoping this is our moment where women don’t allow that and don’t discredit one another. Finally, all of these extremely credible women with proof have come forward and more are coming forward every day. And I think we need to believe women at least as a starting point to investigating these cases.”

Moving toward meaningful change

Though the scope of the problem is staggering, there are lessons to take from this moment of reckoning. Harvard scholars offered up an array of suggestions for how to cope with and move forward through the ongoing wave of revelations.

Dealing with emotions can be an important first step. How to manage our feelings when confronted by ongoing press reports of sexual assaults and allegations is complicated, challenging, and charged, said Stephanie Pinder-Amaker, director of McLean Hospital’s College Mental Health Program and an instructor in psychology at Harvard Medical School. Victims, perpetrators, and those who feel complicit by their silence or simply stunned by revelations about people they know will cope differently. But common frameworks can help guide those struggling with a range of difficult emotions.

Parsing the language is one place to start. Instead of saying “moving on,” Pinder-Amaker suggests the term “moving through” as a way to think about navigating the emotional terrain as revelations continue. She also suggests looking to theories of grief that encompass emotions such as shock, denial, anger, sadness, even bargaining or the urge to strike a deal to “make this all go away and not be the nightmare I just woke up to,” that are common when people face the death of a loved one or friend.

“Those are very real, typical and expected feelings associated with a grief reaction and tremendous feelings of loss. These are all part of the stages of grieving, and they are perfectly valid,” said Pinder-Amaker. “Often it’s reassuring just to know these feelings are typical, they are to be expected, and you might feel a range of these within a day and that’s OK.”

Sharing feelings with a trusted friend or family member and taking a break from the 24-hour news cycle are other useful coping strategies, she said. And knowing sexual assault statistics, such as the fact that a majority of sexual assaults are committed by acquaintances and that most of those go unreported, can help promote awareness and ease fears.

“Believing these facts will put all of us in a better position to be empowered to take preventive action and ultimately to protect ourselves, our children, and each other,” she said.

Richard Weissbourd led a survey of more than 3,000 high school and college students that found sexual harassment and misogyny pervasive.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

What should businesses do? Analysts say that sexual harassment training can help but is no silver bullet. Most companies have formal policies against harassment in their employee handbooks, and many require staffers to attend classes, yet research suggests the training can be ineffective if it doesn’t address real-world scenarios or offer credible solutions. In addition, company leaders may signal to subordinates that training is a mandatory human resources hurdle to endure and then forget, rather than an important, expectation-setting mandate.

“The training around sexual harassment is terrible,” said HBS’ Soltes. “There are people who grope people in elevators. That does happen. Training is not going to change that. However, that’s what training focuses on. That’s not the major problem. The major problem is people saying things that they think are a compliment when they’re not.

“I think this is the next step, where firms are going to really need to think very carefully. I’m hoping as researchers we can play a part [in] thinking about how to devise the kind of training that will resonate more deeply with people, so it’s not simply legal cover but is actually trying to nudge people to treat one another respectfully in the workplace,” he said. “But I think we have a long way to go before that occurs.”

Ely believes that addressing the work environment is essential. “The way I look at all gender issues in companies in general is that it’s always a problem of the workplace culture, whether we’re talking about sexual harassment or sexual assault or even just the implicit, inadvertent acting on biases,” she said.

Research has found that some organizations become places where behavior that was once outrageous slowly becomes normalized, “because it’s just one thing leads to another and people feel like, ‘Well, nothing ever happens, so I’m not going to report anything,’” she said. “And once in a while, there’s a case that comes up, and then it’s like, ‘Oh well, there’s a bad apple.’ It’s not a bad apple. It’s a culture that’s giving rise to this kind of behavior and letting it persist, not necessarily consciously, but …”

An important first step for companies is to bring in outside entities to assess how employees experience the culture, she said. But then it’s up to corporate leadership to make things right.

“I do think it’s the responsibility of companies to look at their culture with a really critical eye to understand how does that culture differentially affect different groups of employees — because we know it does,” Ely said. “I don’t think this is an H.R. thing. It’s not something you can legislate with policy. It’s something that leaders need to take up as their own agenda, to really be invested in understanding how people experience the culture of the organization, a culture that they, as leaders, are responsible for, whether they like it or not.”

That’s a tall order, in part because company leaders typically rise to the top by successfully negotiating the same workplace culture others perceive as hostile. Once in command, even if they are well-intentioned, they have only their own positive experiences and vantage points to draw from.

To prevent some men from abusing their power, Soltes said, companies should stop protecting high-status offenders. “I’m hoping that part of this is a turning point for the role that senior management, boards, and attorneys play. That simply creating these watertight legal contracts and NDAs is not sufficient to protect, so to speak, the organization.”

But firms also must make organizational norms clear and nip offensive behavior in the bud to create a fairer and better culture for all. “The main goal is not firing people,” Soltes said. “That’s a necessary punishment for some … but what we want to do is not have this happen in the first place. That’s what would benefit everyone most.”

Government too should play a major role in curbing sexual misconduct. In Washington, D.C., a city built on power, sexual abuse and harassment is a bipartisan problem that lawmakers have only begun to address. In addition, politicians are among those implicated, including the recently announced departures of Republican Reps. Trent Franks and Blake Farenthold, both of Texas, Democratic Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota, and Democratic Rep. John Conyers of Michigan.

Using data to change behavior

The Women and Public Policy Program at HKS works to identify data-driven ways to reduce gender inequality, especially in the workplace. Because many work environments — whether in offices, on factory floors, or in classrooms — were originally developed for a predominantly male population and men still far outnumber women in supervisory positions, bias against women can be built into the systems that shape who gets hired, who gets promoted, how much they’re paid, and how they’re treated.

Because implicit bias is unseen, researchers are studying how to remove it from workplaces through “nudges” that help organizations operate with less gender mistreatment. A nudge can involve blind evaluations that remove demographic characteristics when reviewing resumés, helping overcome assumptions about who might succeed in a job and who wouldn’t. In addition, having men help with harassment training increases their support and understanding of its import, research has found.

“It’s really difficult to change people’s mindsets. It’s much easier to change environments that make it easier for people to make the right decisions,” said Nicole Carter Quinn, the program’s director of research and operations.

An initiative launched this fall, “Gender and Tech,” will bring behavioral scientists and technology researchers together to study and develop interventions to root out bias against women in recruitment, retention, leadership, and promotion in the overwhelmingly male-dominated tech world, where women routinely face discrimination and sexual misconduct, as former Uber engineer Susan Fowler chillingly documented in a blog post earlier this year.

Education appears to have a central role in changing attitudes as well.

The #MeToo movement has shown how sharing personal experiences can promote conversations leading to change. According to a recent Harvard survey, another kind of frank dialogue is needed, one that has parents and educators talk with their children and students about harassment, as well as about what it means to have healthy, loving romantic relationships.

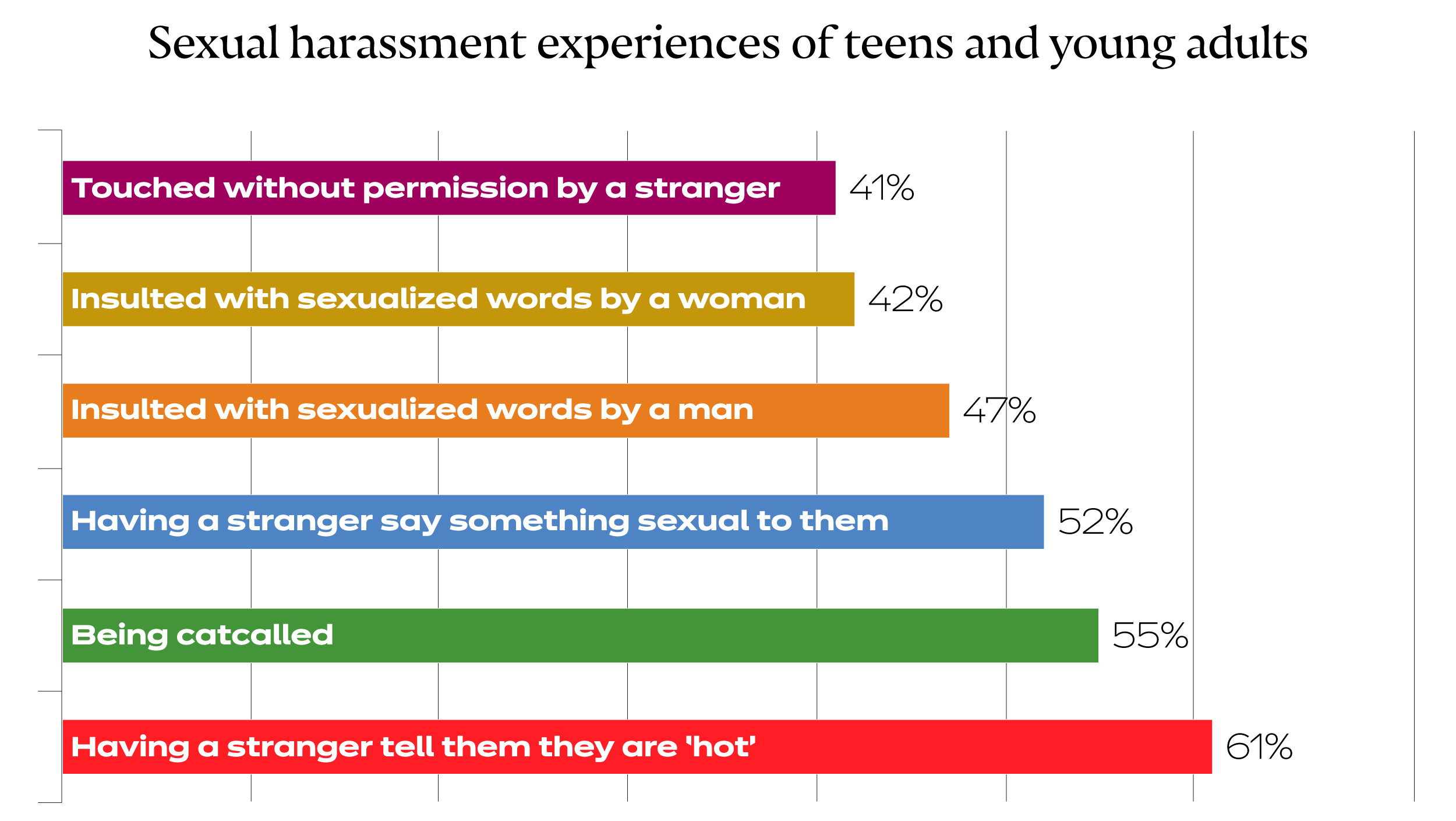

Compiled by Making Caring Common, an initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE), the 2017 report is based on surveys of more than 3,000 young adults, including college and high school students, and aims to create a better understanding of how young people think about and develop romantic and sexual experiences. The study included information gathered from conversations with 18- to 25-year-olds, parents, teachers, coaches and counselors. According to the findings, sexual harassment and misogyny are pervasive among young people. The report suggested that such behaviors and attitudes often go unchecked because parents, educators, and peers don’t intervene.

“I think it’s an epic educational failure, really a staggering educational failure,” said Richard Weissbourd, senior lecturer at HGSE, faculty director of the Making Caring Common project, and the study’s lead author. He hopes the report will act as “a real wake-up call.”

The statistics were taken from the 2017 survey “The Talk: How Adults Can Promote Young People’s Healthy Relationships and Prevent Misogyny and Sexual Harassment,” published by Making Caring Common, a project of the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Graphic by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard staff

Some 87 percent of young women surveyed reported being sexually harassed. Forty-eight percent of respondents either agreed with or were neutral about the statement “Society has reached the point where there is no more double standard against women.” Roughly three-quarters of respondents said they had never had a conversation with a parent about what constitutes sexual harassment. Parents, the report said, engage in a “dumbfounding abdication of responsibility” by delegating their children’s knowledge of romantic and sexual relationships to popular culture, where song lyrics, movies, television, video games, and magazines are rife with misogynistic messages and content, and harmful notions of romantic love.

The researchers found that degrading language is prevalent in school hallways and classrooms, where words like “bitch,” “slut,” and “ho” are so common that they are “part of the background noise,” said Weissbourd. The report also said that boys regularly divide young women into “good girls” and “bad girls” and binge on internet pornography.

“That reinforces just about every unhealthy and degrading notion about sexuality there is. It’s the degradation, the objectification, the idea for boys that what’s pleasurable for you is pleasurable for women. The idea that women are there to service you, the sense of entitlement that it can engrain,” said Weissbourd.

He said that parents and teachers need to go well beyond platitudes like “be respectful” to others or discussions of abstinence and safe sex, and instead, engage young people in meaningful discussions.

Reframing the definition of masculinity, Weissbourd said, is another important step in the way forward.

“Young men need to learn that there can be real courage and honor in learning how to have a healthy love relationship with somebody else — the tender, generous, subtle, courageous, demanding work of learning how to love and be loved. I really think that we’ve got to push a very different definition of manhood here.”