Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘It seemed to me miraculous that you could actually hear Shakespeare or Keats speaking from the page’

Helen Vendler’s encounters with reverie

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

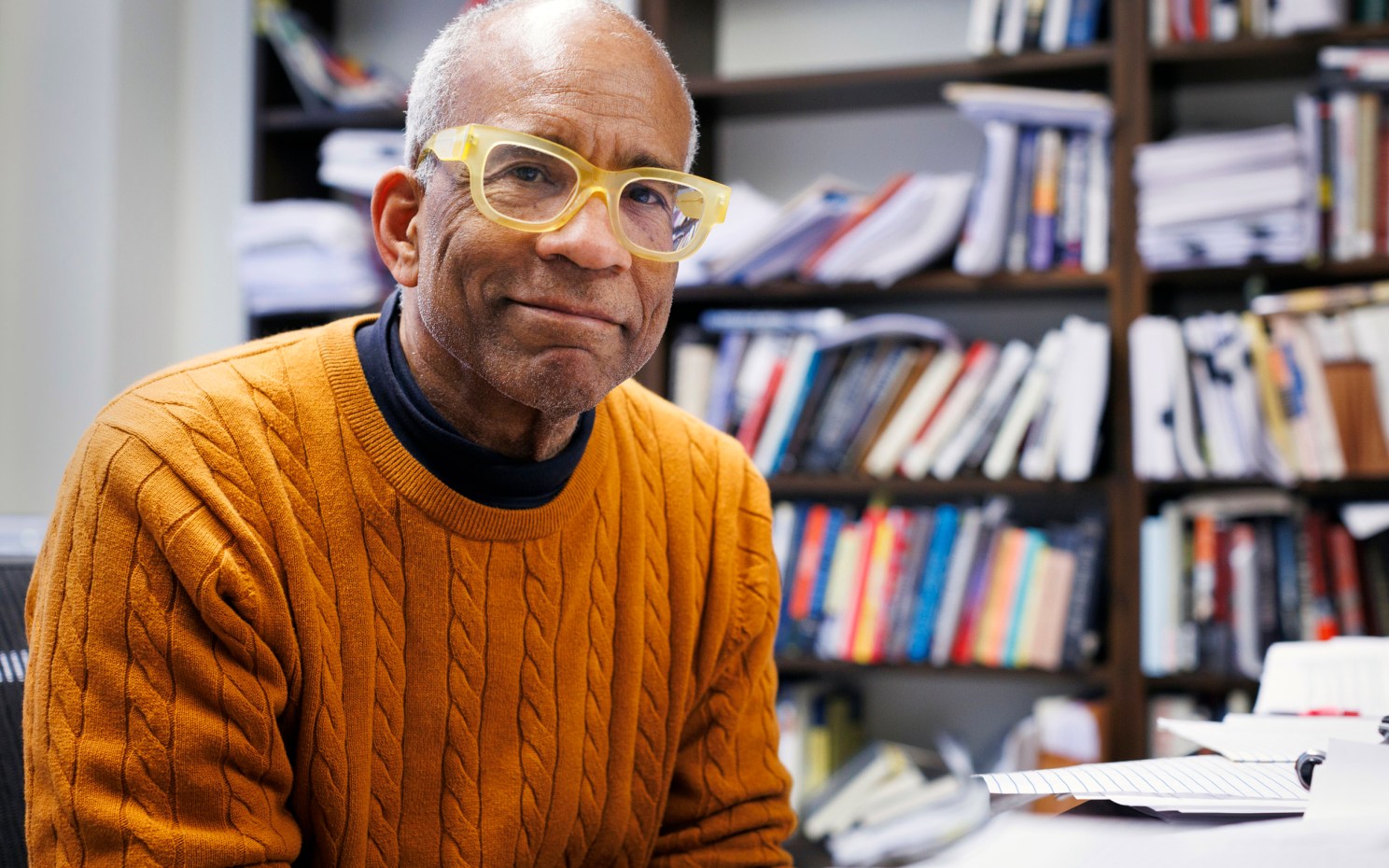

Helen Hennessy Vendler, born in Boston in 1933, is the Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor and one of the foremost critics of English and American poetry in the world. She is the author or editor of 31 books, her first in 1963; earned her Ph.D. in English and American literature at Harvard in 1960, after studying chemistry and mathematics as an undergraduate at Emmanuel College and winning a Fulbright fellowship; and taught at Cornell, Swarthmore, Haverford, Smith, and Boston University before returning to Harvard in 1985. In 1990 she became the first woman to be named a University Professor.

Vendler spoke her first word at 9 months; wrote her first “poem” at 6 (a writing pursuit replaced by her dissertation at 26); learned Spanish, French, and Italian before age 12; roamed eagerly through the stacks at Widener Library while still in her Catholic girls’ school uniform (“I was a sight,” she said); and as a high school senior wrote what she calls with some amusement “my first book” — a 40-page exploration of the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

From the study of manuscripts, she learned that poems grow in unexpected ways and that no artwork lacks many underlying structures. All that set her on a lifelong path of reading single poets at great depth, and of looking at a poem as an evolving artifact with unexpected turns, while mediating the poet’s urgent themes. In her youth, Vendler considered a career in medicine. But she soon returned to her first impulse: “Poetry was too natural to me to be forsaken.”

Could you tell us about childhood inspirations and influences?

My mother had been a first-grade teacher. She knew a lot of adult poems, children’s poems, and children’s songs. So I began to sing little first-grade songs early on.

My mother was at home. I think the most important cause of my being here [at Harvard, as a poetry scholar] was the fact that my mother was prevented from teaching after 14 years in the classroom. You couldn’t teach in the Boston schools if you were a married woman, because “it would be taking the bread out of a breadwinner’s mouth.” When my parents married, in 1930, it was at the height of the Depression.

[Not teaching] made my mother deeply unhappy, as it would make me unhappy if I had to stay at home all day with three children and no car. So she read to us a good deal. She sang to us a lot. And she encouraged me — I should say both parents encouraged me — when I started to write horrible little poems when I was 6. That’s, I think, what started my interest in poetry.

What about books?

The enclosed back porch was off the kitchen and had steps going down to the backyard. It was lined with bookshelves and my parents’ books. At about 12, I decided to catalog them all, lining them up in various groups and making little labels for the spines. That way, I could find whatever I wanted to go back to. I did know the contents of those shelves well. And then there were other books around the house, too. My mother read a good deal of religious literature, but all the anthologies in the house were of poetry.

What about your dad?

He taught in high school — Spanish, French, and Italian. He was bilingual in Spanish from having lived 14 years in Puerto Rico and Cuba, so he spoke Spanish to us.

He took it upon himself to teach my sister and me (my brother escaped) Spanish, French, and Italian. For Christmas we never had presents, but my father ordered books from foreign parts. We would have a book in Spanish and a book in Italian or French. I felt, and feel, different about Spanish; it was like a mother tongue. My father read and sang to us in Spanish every night.

How did being at Emmanuel College in Boston propel you to explore poetry?

I intended to be an English major, understandably enough, but I didn’t like the way that literature was taught as a branch of Catholicism.

I tried the concentration in French in my second year and discovered that in the survey of French literature, you couldn’t read the authors you’d have expected, because they were all on the Index of Forbidden Books. No books by Voltaire, Diderot, Pascal, Proust, Flaubert, Baudelaire. They were all on the Index (which subsequently was abolished).

My parents wouldn’t let me leave Emmanuel, and I thought “I have to go into a field where they can’t corrupt the curriculum.” So I went into science: I became a chemistry major, and took the requisite physics and biology and mathematics courses, enjoying it all very much because it couldn’t be corrupted: it was truthful.

I think every young intellectual sets truth as the highest value. Why study something seriously if you didn’t want to find out what was true about it? Lyric poets are necessarily honest, candid, straightforward about their feelings, no matter what their poetic manner or personal abstract symbols.

What was your plan after studying chemistry?

I took the medical college admissions test, thinking I might be a doctor. I had become interested in medicine because I was Rh-negative, and at that time not the first baby but the second baby, if Rh-positive, was threatened with death. When I read about it, horrified, I launched myself into medical reading. That, too, was a different world from home, because nobody in my house ever spoke about whatever was between your front and your back. [Laughter.]

But like most people who are going to be different from their parents, I wanted very much to escape from my parents’ house. I had been awarded a Fulbright in mathematics, and it took me to Belgium. When I arrived, after 10 days at sea thinking about my future, I wrote to the Fulbright people and said I’d made up my mind to do graduate work in literature, and would they mind if I did literature instead of math? They said, “Not at all, dear. Do whatever you want.”

I knew by then that I wasn’t going to go ahead in math, though I had loved it. Geometry, with its shapes and volumes, taught me about poetic structure, and so did organic chemistry, because of the variety of structures of three-dimensional molecules.

I love structures. They were, in a way, what I was able to convey in my writings on poetry, because I could see the skeleton beneath the skin. And poetry was a mobile structure, changing from opening to close. It’s no accident that [John] Ashbery called one of his books “Flow Chart”: in a chemical flowchart, you begin somewhere, and then the chemical reaction evolves: finally you end up with the product you were aiming for. You have to plan the course of the experiment and write the equations for the many steps of combination and distillation and so on. That practice gives you a firm way of thinking sequentially.

I’ve always been interested in the internal shape-changes of the poem. In my student days, it was common to assume that the poem makes a statement — that it’s protesting war, or is grieving a death. My teachers, on the whole, didn’t see a poem as an evolving thing that might be saying something completely new at the end because it had changed its mind from whatever it had proposed at the beginning. I was sure you couldn’t sum it up propositionally: You couldn’t say, as it was common to say, “What is the meaning of this poem?”

“I love structures. They were, in a way, what I was able to convey in my writings on poetry, because I could see the skeleton beneath the skin.”

So when you say evolution, were you looking back in those days at the poem as a fixed entity, or did you go back to manuscript?

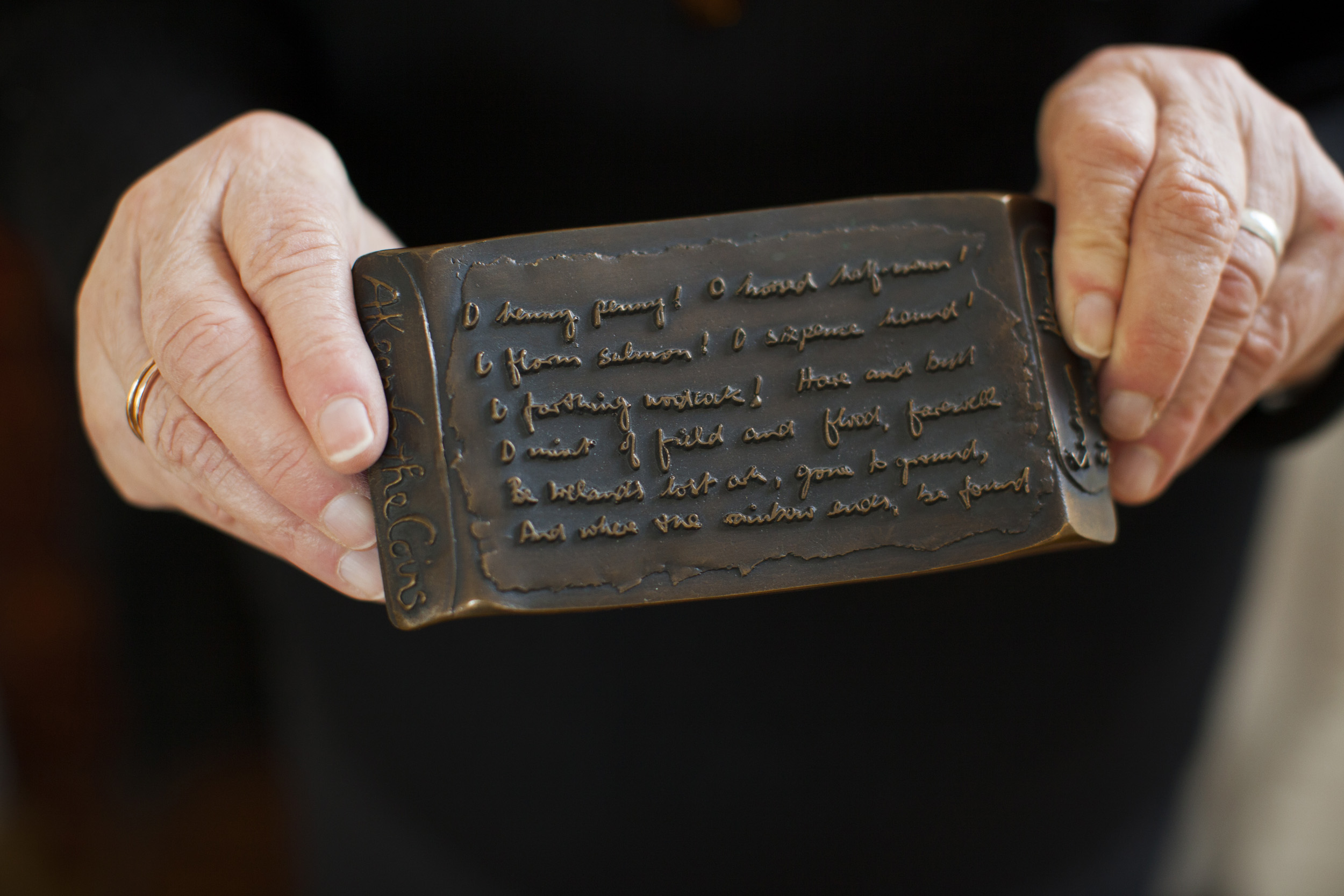

I understood it as a developed manuscript. I was 12 [when] I saw my first set of manuscripts in a little book called “Poetry for You” by Cecil Day-Lewis, the father of Daniel Day-Lewis. I found it in my local public library in Roslindale. Day-Lewis printed successive drafts of his own poems, and I thought, good heavens, they’re not born in their final form on the page. They are actually things that start from almost nothing, or from — as I learned later — a rhythm here or a word there or a proverb somewhere. At 15, I became intensely engaged with Dylan Thomas’ poetry and found out that his manuscripts were in Buffalo [in the Lockwood Library, the University of Buffalo]. I asked for the loan of their microfilms and read them all with enormous profit. There were as many as 30 drafts for “Fern Hill,” for instance.

Thomas was a sedulous reviser. The drafts helped me to solve the more difficult poems, too: Reading them in draft was a way to understand them better.

You were a 15-year-old who studied manuscripts. Even in college most English majors don’t do that.

It was all from Cecil Day-Lewis. As I saw the drafts of his poems, I thought, “That’s it. You can find them as they grow.”

So these 30 drafts of “Fern Hill,” for instance, what did you —

I was set up at the microfilm reader [at the Boston Public Library]. I sat at the screen for hours and hours, week after week. The librarian in Buffalo began sending me books and journal articles on Thomas as well, on his own initiative.

That sounds like a transformative experience for a young reader of poetry.

It was. I had begun to write poems again when I was 15, and seeing how Thomas constructed a whole out of fragments gave me an idea of how I might put together a poem.

From Dylan Thomas, where did you go? Did you dig into other poetic passions?

Yes. My mother had brought back from the bookmobile a biography of Hopkins which quoted many of his poems. I began to read Hopkins with great elation and memorized much of what I read. I wrote what was supposed to be a 17-page high school senior paper, only it turned into a 40-page essay. [Laughter.] I think it was my first book. And it gave me my first taste of critical competence: by then I knew everything Hopkins had written — the letters, the sermons, the devotional writings, the biography. It’s not a big corpus.

It was exhilarating to write at length from knowledge of a single poet’s complete works, since anthologies offer only little snippets. I very soon grasped how rewarding it was to write on a single poet. I’ve never written on themes except as elements in the changing explorations of a poet, the evolution of the author’s poetics from the early juvenilia all the way up to the end.

In college, how did you maintain your fascination with poetry while studying chemistry, physics, and math?

Poetry was too natural to me to be forsaken. As soon as I discovered that voices of dead writers spoke in living tones, I became absorbed in the phenomena of those voices. It seemed to me miraculous that you could actually hear Shakespeare or Keats speaking from the page.

“No philosopher would be satisfied with the poetic treatment of any ideas. Yet poems are usually taught, mistakenly, as embodiments of ideas rather than enactments of a mobile consciousness.”

Back then, would you have called poetry your avocation?

No. It was always central to me. It connected me to my own emotional life that was struggling to appear in my poems.

Later, in Belgium, was there anything about the Fulbright experience that transformed your relationship to manuscripts or the way to read or understand a poem?

I wasn’t occupied with that there, but with languages — studying Old French and Italian and French literature. However, I did want to see the Hopkins manuscripts at Oxford, and was granted permission. I made my way to England over the Christmas break, and went to Oxford immediately. I had no idea it was Boxing Day.

I rang the doorbell at Campion Hall. An old porteress came out to the door. I proffered my letter from the Jesuit superior giving me access to the materials. Well, she’d see what she could do. She took me to a parlor, disappeared, and then returned bringing me, in succession, boxes of completely uncataloged things — poems, the tutorial essay that Hopkins had written for Walter Pater with Walter Pater’s signature, drawings that Hopkins had done — all in a sort of chaos. I obviously couldn’t tackle the material at that point, but I could see how rich a source the archive was.

Although I had viewed the Thomas manuscripts, that was on microfilm, and was quite unlike seeing cartons full of the handwriting of Hopkins in poems and letters.

Manuscripts are one way to get at a poem. How about explication?

I don’t think poems have much to do with ideas. Philosophy may, but poetry doesn’t. In any case, when [poets] employ ideas they use them as raw material, subject to the laws of form like any other ingredient. No philosopher would be satisfied with the poetic treatment of any ideas. Yet poems are usually taught, mistakenly, as embodiments of ideas rather than enactments of a mobile consciousness.

What propelled you into graduate school?

I had been coming to Harvard [with my father’s card for Widener Library] since I was 15. I was here, usually after school, wearing my ridiculous school uniform — navy blue serge, with white collar and cuffs, brown tie oxfords, and a “Miraculous Medal” around my neck. I was a sight. Once the librarians saw how many books I was sending for, they offered me a stack pass and I was transported.

At the same time, I was coming often to Harvard for poetry readings. When I was 17, I heard Eliot here — giving the Spencer lecture, not reading his own poems. During high school and college I heard almost everyone: Frost, several times; E.E. Cummings presenting his “Six Nonlectures”; Dylan Thomas, who read “Under Milk Wood” doing all the voices himself, in a spectacular evening. I didn’t know anything at the time about Welsh literature, and that flood of language was entirely surprising and winning.

When the year was up, I committed my only deliberate crime, which was to spill ink on the expiration date of the Widener card. I couldn’t bear to give up Widener: whenever I walked in, it made me happy. Then one day, the librarian looked down and said, “Hasn’t this card expired?” It had, of course. So I was expelled from Eden — but thought “I will be back,” even then.

After the Fulbright, what came before graduate school at Harvard?

I wrote from Belgium to the chairman of the English Department [at Harvard] and said, more or less, “I have a degree in chemistry, and I’m now on a Fulbright. Can I come and do a Ph.D. in English?” He said, “No. You are not a suitable candidate.” I wrote again, asking how I might become a suitable candidate: “Go somewhere and take some English courses and then you can reapply.” When I returned from the Fulbright, I entered Boston University as a special student and took several graduate courses in English.

The best teacher I had there was a professor named Morton Berman, himself a Harvard Ph.D., who taught Victorian literature. Most professors were still teaching literature as either history or philosophy or [as a way] to form a virtuous gentleman, as Spenser said. English teachers then were often the sort of people who would have been vicars of a parish in another age. Essentially they were giving moral commentaries on literature. But Morton Berman was talking about the literature itself and so I was thrilled to be led into a literary discourse that became native to me.

How would you have described what literature is, if it isn’t this pathway to moral behavior?

It’s an art that always arises from passionate feeling, but it must be composed with profound technique. However abstract its symbolic expression, it is something deeply seated in the emotional life.

Yeats’ poem “The Moods” became for me a touchstone, to use our old word. Yeats declares that time destroys everything except the moods, because they are eternal. Human beings everywhere and at all times experience grief, doubt, anger — whatever mood it might be — and moods are therefore the proper subject of lyric. They’re “fire-born,” says Yeats — eternal — and are never absent from any culture.

Was this perception at odds with graduate study in that era?

With very few exceptions, yes. I.A. Richards, whose class I audited [at Harvard], knew what poetry was and taught poems very dramatically.

In his classroom, the lights were turned off, and [Richards] put the poem up on a screen. With a long wand, he would point to a word on the high screen and talk about it for a half hour. He lectured on only 12 poems over the course of the semester, one poem a week. But that gave me an insight into how very rich poems were.

[Richards’ approach] was basically philological. He knew Latin and Greek and could talk about any one word enchantingly. His lectures were also philosophical, because he was interested in the evolution of philosophical ideas over time. But he made philosophy part of the poem rather than the poem part of philosophy.

Tell us about your other great teacher at Harvard, John Kelleher.

He had been a junior fellow here. I didn’t know anything about Irish literature, so I first took Kelleher’s course in Irish poetry and prose. Then I went on to his seminar on Yeats.

I got very much interested in Yeats’ “system,” as it was called. Blake had written “I must create my own system or be enslaved by another man’s.” Yeats edited Blake, and perhaps that led him to create his own system, under the title “A Vision.”

My dissertation, which became my first book, was on that system and its connection to his late plays. I wasn’t interested in the plays as drama at that moment; I wanted to explain how Yeats was structuring his imaginative universe with its peculiar psychological system of gyres, and phases of the moon, and historical change.

So we’re back to geometry in a sort of way, aren’t we?

Yes. [Laughter.] The cones and the cylinders.

Was being a woman a detriment along the way in your early career?

Yes, with some people. One had to have one’s study card signed by the department chair. I walked in and introduced myself: “I’m Helen Hennessy.” His immediate reply: “You know, we don’t want you here, Miss Hennessy. We don’t want any women here.” That was my welcome to Harvard graduate school.

Hearing from a friend, 13 years later, that I still remembered that encounter, he stopped when our paths crossed at the MLA and brought it up. I tried to say that it was water under the bridge, but he insisted: “No, I was wrong. I apologize.”

There were lunacies everywhere that went with being a woman. When I arrived to teach at Cornell, for instance, I couldn’t have lunch with my husband because women faculty were not permitted to be members of the Faculty Club. It was exclusively male. That was in 1960. The following year, largely because of lobbying by some admirable men in the club, we were admitted by a vote of 52 to 48. A narrow victory.

Your first book was published while you were at Cornell. Can you say why you wrote books on single poets (Yeats, Stevens, Herbert, Keats, Shakespeare, Heaney, Dickinson)?

I can understand poets only one by one: They are too idiosyncratic to be lumped together.

Each book had a polemical purpose: to declare that Yeats’ “system” had powerful poetic implications; to argue that Stevens’ long poems were not “ponderous and elephantine”; to contest the belief that Herbert could be appreciated adequately only by a faithful son of the church; to show that Keats’ odes had been insufficiently well read, and were in fact interconnected as a series; to assert that Shakespeare’s sonnets, all 154 of them, not merely the famous ones, deserved individual commentaries; to offer an alternative to the Irish political criticism that had neglected Heaney as a poet; and to suggest that Dickinson’s harsher and more difficult poems could, and should, be read by a wider public.

All these years later, after decades of poetry scholarship, what still sustains you?

What always did: reading, thinking, writing, teaching. And life itself: bringing up a son, seeing tragedy in the family, being granted friendship — all of life feeds into one’s responses to poetry.

Is your sense of the state of the humanities as hopeful and expansive as it was 20 or 30 years ago?

We’re going through a kind of convulsion, at the moment, in which we are thought of as useless.

Is that connected to how English and related subjects are taught?

Elementary and high school literary education in the United States is pretty awful, for many reasons, historical and cultural. Poetry is taught in the schools in a completely irrational way — a unit on this and a unit on that. There’s no rational progression to advanced learning in the subject. Science and mathematics textbooks have progressions that reinforce each other, whereas poetry “units” are not progressive, do not build on each other, and present a sanitized curriculum. In many schools, my students tell me, poetry has been dropped altogether.

Yet poetry and the arts can be so liberating. You once referred to first studying literature as an escape from “religious incarceration.”

In the Roman Catholic community in which I was raised, girls had no possibility of leaving home. I had no independent means. And, in a Catholic home, the only conceivable futures for a girl were to be a nun or a nonworking mother or an elementary school teacher or a spinster caring for aging parents. If you married, your husband would be a good Catholic, and you would have “as many children as it pleased God to send you.” That was the way it was put. I didn’t want to be any of those things.

I had never been out of my childhood environment. I knew nothing of the world, and had in effect been raised in the Middle Ages. I couldn’t imagine what my life might become. I had no role models for single life except the nuns. I didn’t know any women who were living a life that entailed the kind of thoughts and reading that I was already engaged in. I just didn’t know where you went if you were that sort of woman. My parents always intended me to go to college, but never spoke of a later career in the world.

But on the other hand, you talked about growing up in perhaps a self-created world in which words had great power and meaning very early on. I think you talked about, what, saying your first word at age —

Nine months. [Laughter.]

I think [awakening to words] is like awakening to any other precocious appetite.

I once asked Seamus Heaney what he did with the part of his mind that wrote poems before he wrote poems. Right away came the answer, “marquetry”: little pieces of wood all fitted into little puzzle shapes. And of course that’s exactly like the surface of a poem. You have to get all the words dovetailed and matching and get the right sizes together and the right colors in the right place.

But then [Heaney] paused, and I saw that marquetry wasn’t the whole answer. And then he said, “Fishing: the leisure of trawling around the bottom to see what, if anything is going to make a jerk on the line.” And I thought that a wonderful answer: marquetry and fishing, surface and depth.

You have referred to the structure of lyric poetry as concentric.

Well, it’s concentric and vertical, I would say. It’s like a well: You have to keep going down in the same place. You don’t arrive anywhere, as in linear narrative; you’re not fighting anything, as in drama; but you are trying to get down deeper, to explore and evacuate a site of feeling.

That goes along with your idea of lyric poets as inventors, constant reinventors of our beautiful poetic genres.

I was just saying that in class about Seamus. No genre escaped him unchanged —the sonnet, the elegy, the pastoral, the villanelle, the journey poem, the protest poem, the poem of the invisible.

Elegy is such a well-known form, but who before Heaney would have elegized bog bodies as he did in “The Grauballe Man”? To take those arresting bodies that have been dead for hundreds of years and write about them as sculptural and tragic: Nobody had done that before.

The Catholic tradition out of which Seamus came assigns the dead to an afterlife; but Seamus portrays them as bodies slowly decaying in the earth, partially preserved into an eerie beauty by the tannin and the peat. … His poetry is always a rebellion, but a rebellion within the tradition: one afterlife against another.

Somewhere along the line you decided that you weren’t a poet yourself.

I wrote poems from the time I was 15 until the time I was 26. And I took them seriously; I made them as good as I could. But then — it must have been when I was in graduate school — I came across a sentence of Coleridge’s talking about “that perpetual reverie in which I live.” I thought, “What can that mean, to live in a perpetual reverie, to inhabit an incessant internal dream?”

I think I didn’t know what a life of reverie was. I was, as they say these days, a task-oriented person. It gives me a sense of completion of the day to have finished something. But of course true art is never finished: the imagination is for artists a place of alternative life. I don’t have that kind of imagination: I have a more analytic mind, which is, I suppose, why math and science appealed to me in my youth, and why literary criticism became my natural field.

You’ve lived through an era in which poetry was taught differently, perhaps better than it is now. Are we missing something?

I don’t feel as though things are better or worse. Present or past, for any art, there are many responders, as with wine: There are expert wine tasters, with much experience; and then people who like a good wine; and then people like me who can’t tell one wine from another. In every field the mediocre are around, the incompetent are around, the gifted are around.

Yet the humanities seem to have less power in our culture than they have ever had.

In learning, everything depends on reading. Whether you’re going to do science or history or anything else, adult intellectual accomplishment depends on being able to read widely and well and with enjoyment.

Judging by the results from the schools, few children are proficient in reading at the fourth grade. They don’t read fast, they don’t read with understanding, they don’t read with appetite. If you’re not a good reader by the time you’re in the fourth grade, you’re probably never going to be one.

I wish we could have, for the first four grades, the children taught “reading” in every conceivable form: singing, putting on plays, reciting, looking up words in the dictionary, memorizing, reading aloud, being read aloud to. They could learn verbal rhythm by marching and singing and dancing. For the first four years, the chief aim would be perfecting reading, in all these ways. Then the children could undertake other subjects — when they could actually read history, read geography, read science.

If we could induce children to read with pleasure, and to feel the connection between thought and expression, their education could progress. … With immersion in reading practices, all becomes possible.

Did you ever imagine yourself doing anything else?

I seriously thought I might be a doctor. I would have enjoyed the act of diagnosis. Any medical case is a puzzle until suddenly the elements come together and click into shape just as poems do.

Why lyric poetry now? You discovered a “why” in your youth. Is there still a “why”?

Yes, because it is the most precise articulation of “the history and science of feeling” (Wordsworth). It is a ground of reality. God knows television and video games can’t be the ground of emotional reality.

Lyric poetry still seems to me, in its seamless fusion of imagination and technique, the symbolic ground of a comprehensive and constantly changing enactment of the life of consciousness.

You know, I’ve come to think of that as being the fundamental gift of the humanities — to defy the idea that there is one truth.

Art is anti-ideological from the start. When ideology dominates, you publish Pravda. As our poet A.R. Ammons says, [poetry] is like water going through your fingers — “uncapturable and vanishing.” And people don’t like the uncapturable and the vanishing, by and large; they respond to more solid direction, whether religious, moral, or political.

Practitioners of the humanities have to sell the idea of that handful of moving water, shaped briefly to the hand, and then gone. But what about colleges and universities faced with shrinking humanities faculty departments and research money?

In our pioneer country, useful people were prized, and useless people were not. The dissenters who came here were not from the aristocracy. They didn’t bring over the amusements of the elite, the court entertainments of music and madrigals and masques. Those things seemed to the dissenters to be dissolute practices of the indifferent aristocracy. There was a deep suspicion here of the arts and secular learning as distractions that took people away from God and religious duty.

Do you think embracing the humanities, embracing enduring forms of art and culture, is something that America will grow into?

Yes, after we’re a thousand years old. Europe is a thousand years old, and has become proud of its cultural patrimony. We eventually will be proud of ours.

We don’t teach our great poetry in the schools. We don’t teach our great art in the schools. We don’t teach our great music in the schools. We don’t yet have a sense of an American aesthetic and scholarly achievement that we must transmit as part of our being in the world.

Yet the decline of interest in the humanities seems to be international.

That’s the result — though not necessarily a linked result — of modernity and democracy. Modernity requires usable engines, from atom bombs to space stations. And democracy is thought to require that you not teach anything that not everybody can understand.

Q: Has the rise of visual culture taken a toll on the humanities?

Yes: Everyone can look, even if not profoundly. But not everyone can read, or read complicated texts.

That form of looking, that incessant presence of things to look at, moving things to look at, seems to be anti-reverie —

It’s anti-reverie and it’s also anti-literacy and anti-conversation. You can’t be reading while you’re looking, and you can’t be looking while you’re reading. Nor can you converse intimately while the screen is occupying your attention. Nor can you write while you’re watching something visual. On the other hand, both the Web and TV offer so much to bright children who don’t find those texts or images at home or at school. A smart, hungry pupil can have the best public library in the world at hand. That can’t be bad for America.

There is this inbuilt hunger to learn. You can’t crush that.

No. Students may be learning in different fields in different eras. In Shakespeare’s time the main way you could advance was to be trained verbally. The indispensable skills were oratory, eloquence. These days, not even the “best” schools offer that intense training in language: social status is not gained by translating Greek and Latin.

The studies that are prized in the way of learning now are indeed the STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] subjects, just as the arts of reading and writing were praised and prized in the Renaissance. Our era will discover new aspects of learning: You won’t get Shakespeare’s plays, but you may get the explanation of dark matter. I don’t regret this, as long as there’s support for earnest students of any bent.

Even if that something isn’t poetry, perhaps?

There were whole centuries without much brilliant poetry. Whenever warfare occupies the resources of the state, there is less support for the arts, less patronage available for poets. Poetry may suddenly become important again here, as it did during the political troubles of Ireland and Poland not long ago.

You refuse not to have hope, don’t you?

I just have faith in the gene pool. The gene pool is always casting up musicians, poets, people who want to create theater, as well as scholars and teachers.

Is there something that you’d like to add about where you came from?

An intellectually hungry and often dissatisfied and rebellious young person will look around for wherever there is fosterage — libraries, teachers, concert halls. But you have to start with a yearning for knowledge and delight.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.