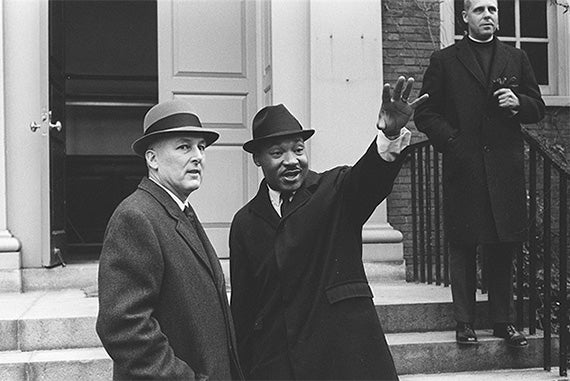

Professor Harvey Cox (pictured) first met Martin Luther King Jr. in the late 1950s. “It turned out that we were born the same year, we were both Baptist ministers, we both had a strong interest in the theologian Paul Tillich,” Cox recalled. “So we formed a kind of a friendship that continued.” In the 1960s, when Cox was a Harvard doctoral student, King asked him to create a Boston branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

My memories of Dr. King

Harvard Professor Harvey Cox reflects on his friendship with Civil Rights leader

Harvey Cox was a Harvard doctoral student in the early 1960s when his friend the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called and asked him to help create a Boston branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the influential Civil Rights organization that King helped found in 1957. Cox recalled, “I said to him, ‘Well, Martin, sure, we’ll do something. In Boston, we don’t consider ourselves particularly Southern.’ He said, ‘We’d like to keep that name.’”

Starting in 1962 and for the next few years, Cox recruited people for Southern Civil Rights marches, rallies, and demonstrations, where nonviolent protesters often were repeatedly attacked by police and local authorities. King’s thinking at the time, said Cox, Harvard’s Hollis Research Professor of Divinity, was that “the publicity of sympathetic Northern folks being there would tame the violence a little bit and provide wider publicity.” Cox took part in several protests, including two marches from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. The two men remained friends until King was assassinated in 1968.

Reflecting on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the Gazette spoke with Cox about his friendship with the Civil Rights leader and his lasting legacy.

GAZETTE: How did you meet the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.?

COX: We met way, way back when I was chaplain at Oberlin College. That was back in the late ’50s, when Dr. King was leading the Montgomery bus boycott. He was a young, unknown minister at the time. Nobody knew much about him, but they’d heard a little bit about this bus boycott. I invited him to come and speak at Oberlin, and he came. This must have been about 1957-58. He came and spent a couple days, and I got to know him very well. And it turned out that we were born the same year, we were both Baptist ministers, we both had a strong interest in the theologian Paul Tillich. In fact, King had written his dissertation over at Boston University on Tillich. So we formed a kind of a friendship that continued.

GAZETTE: As you worked with and got to know him, what was he like?

COX: It was one of those immediate friendships. We had these common interests that were quite evident as soon as we started talking to each other. And so I was impressed. He was serious. But one thing I like to say is the man had a fabulous sense of humor, which doesn’t come across in many of the tributes that you hear or see on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. He could be very funny. But he didn’t do that very much in public. He had a rather serious expression, a serious mien. But he could mimic people, for example. When I was with him on several of these campaigns, he mimicked Lyndon Johnson, [Dallas County, Ala.] Sheriff Jim Clark, and other people, and he had everybody around him just laughing uproariously because he did it so well.

So I got to know him quite well. In fact, he asked me — in 1966, I think it was — to give the main address at the annual meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was taking place, believe it or not, in Birmingham. This was after the Civil Rights Act had been passed, and they wanted to get right back to Birmingham and have this big conference there to demonstrate clearly that there had been a significant victory overcoming the racial discrimination policies of the hotels and the restaurants and all that. So I was there for that, and I consider it one of the main high points in my academic, public life, speaking to that assembly. … I continued to be in touch with him until he was killed in April of 1968.

GAZETTE: Can you tell me where you where that day?

COX: I was over at a conference in North Carolina. I quickly left for home. I did not go to Atlanta to the funeral … but I remember the day, and I felt really quite bereft. I knew that this was going to be a bad day, and for American history. Sure enough, two months later Robert Kennedy was killed. It was not a good year.

But I was especially impressed with Dr. King’s total and unwavering commitment to nonviolence. Toward the end of this career, he was under considerable pressure from other elements in the freedom movement, which is what we called it at that time, to forgo all this nonviolent business. He would not. He said, “If I am the last person in America that’s still advocating nonviolence, I’ll continue to do so.” He demonstrated that you could actually accomplish things that way. He learned a lot from Gandhi, and said that on many occasions. It was Gandhi and Jesus who were his two main instructors.

To tell you the truth, I knew this was a wonderful experience I was having. I was very fond of him. I was very admiring of him. But I didn’t know until 10, 20, 30 years later that I was really in the middle of one of the great chapters in American history and of one of the most significant figures in 20th-century American history. … But sometimes you don’t know that when you are right in the middle of it.

GAZETTE: Were you involved in the Selma-to-Montgomery marches?

COX: I was. There were three marches in 1965. There was the first one, where everybody got beat up. I wasn’t there for that. That was the one led by John Lewis. Dr. King was not there. They were going across the Edmund Pettus Bridge when they were set upon by the police and knocked around and beaten up. And then Dr. King came down for the second march. I was there for that one. We were stopped at the bridge by phalanxes of police, and Dr. King decided to turn back. He asked, “May we pray.” We prayed, and then we turned back. And then there was another march after the Supreme Court issued an order that we should be allowed to march from Selma to Montgomery, so I was there for that one. I have to admit, I didn’t walk the whole way from Selma to Montgomery, but I walked part of the way.

GAZETTE: What was the atmosphere like?

COX: That was celebrative because we had the law on our side at that point. We were protected by the National Guard — a very different scene than from the first two marches.

GAZETTE: What do you consider King’s most important lasting lesson?

COX: He was so utterly committed to human dignity across all kinds of racial lines and other dividing lines. I think the thing that is forgotten so much about him is toward the last two years of his life he got enormously interested in the economic inequality in American life that he thought was so closely tied in with the racial division. Remember that when he was shot in Memphis, he was there supporting the sanitation workers, the garbage collectors’ campaign for a fair wage. He had just organized the Poor People’s Campaign, and they had their tents pitched out there in Washington. He was turning from a more racially inclusive society to one where the economic opportunities were more justly distributed.

And I have thought about him a lot as I have been reading some of the pronouncements of Pope Francis. Pope Francis is saying some of those very same things. We don’t often hear those kinds of views so much on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. But that’s really where he was when he was killed. He was moving away from even from what you might call racial justice, which he certainly was committed to, to a broader and deeper view of the imbalance and injustice in American society.

GAZETTE: Can you compare the protests from your generation to the national protests in recent months in the wake of events in Ferguson and Staten Island? Do you see similarities, difference?

COX: There are some similarities, and there are some real differences. I think, for example in Ferguson, even though there were people there, including some of my students, who were organizing nonviolent demonstrations and protest, the press focused on really a minority of people who were breaking windows and engaged in really violent kinds of protests. Now, we had a little bit of that during the earlier movement, but I think the need to organize people very carefully and long in advance and very well for massive nonviolent protest is something that King and his staff did superbly. …

The Boston protest was a wonderful example of disciplined nonviolence. But these things don’t happen automatically. People have to be prepared for this, even trained for it. We had workshops and things that we did with these young kids who were in those marches in Mississippi and Alabama and so on. And I don’t know how much of that is going on now. I wish more of it were.

Activities for Martin Luther King Jr. Weekend at Harvard

Jan. 17: Harvard will celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. at 7:30 p.m. in Sanders Theatre with “Joyful Noise,” a concert featuring the Harlem Gospel Choir.

Jan. 18: The Memorial Church will commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. during its Sunday service from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Walter E. Fluker, the Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of Ethical Leadership at Boston University’s School of Theology, will deliver the sermon.