Harvard gave R. Buckminster Fuller a gift beyond academics, his biographers say: a lifelong preoccupation with human welfare, and the social, technical, and economic problems that vex the modern age. “R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe,” a two-act monologue performed by A.R.T. veteran Thomas Derrah, explores the life and ideas of the inventor and futurist.

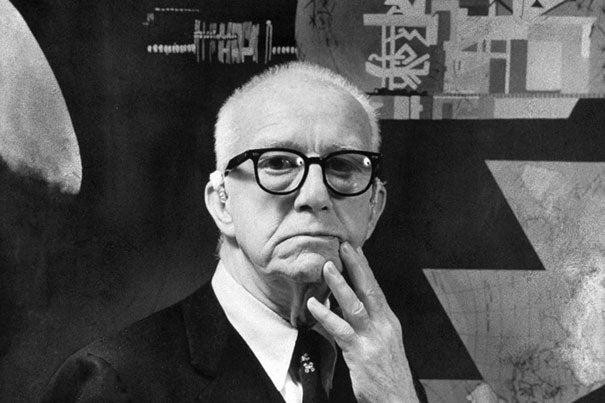

Photo courtesy of the American Repertory Theater

Bucky on stage

One-man play at A.R.T. recounts futurist Fuller’s life

R. Buckminster Fuller, the self-taught architect, inventor, and futurist who coined the term “Spaceship Earth,” entered Harvard College in the fall of 1913. But by 1915, he had been thrown out twice — he preferred the term “fired” — and never returned for a degree.

His first transgression involved using all of his tuition and board money to throw a party for dancing girls in New York City. The second, he recalled decades later, was because of “lack of sustained interest.”

Still, Fuller returned to Harvard in 1961 to accept the yearlong Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry. And he is returning once more, this time as the character in a one-man play at the American Repertory Theater’s (A.R.T.) Loeb Drama Center.

“R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe,” a two-act monologue performed by A.R.T. veteran Thomas Derrah, opens Friday (Jan. 14) and runs through Feb. 5. Director D.W. Jacobs, who began the script after the centennial of Fuller’s birth in 1995, saw him lecture in 1968. “Come whenever you can,” he recalled his brother telling him. “He talks all day.”

Fuller, famously effusive as a speaker, rarely interacted with his audiences. They were hard to see (the nearsighted inventor started wearing glasses at age 4) and hard to hear (Fuller’s hearing was damaged during naval service in World War I). A monologue play was a natural fit, but Jacobs had to pare Fuller’s complicated ideas into about 100 concise stories.

Music and video blooms behind Derrah as the play unfolds, said Jacobs, with sights and sounds streaming “like a wake behind Bucky’s ship.”

And what a ship of ideas it was. Fuller’s admirers over the years called the polymath inventor “Leonardo-like,” a “cosmic surfer,” and a “poet of technology.” He popularized the geodesic dome, invented a streamlined three-wheeled, “Dymaxion” car in the 1930s, and throughout his life was a student of structures that gave materials their invisible tensile strength.

In kindergarten, Fuller constructed a tetrahedronal octet truss out of dried peas and toothpicks, a precocious episode related in the play. In 1961, he patented the same robust symmetrical structure, dubbing it the Octetruss.

At Harvard, Fuller declined to concentrate in math, dismissing it as “too easy.” He turned instead to literature and political science, subjects that ended up suiting him less, and that only accelerated his boredom with conventional studies.

Fuller was restless with conventional thinking even as a boy at Milton Academy. When studying Euclidian geometry, he rejected what one biographer called the “fictitious objects” that notation required. But Fuller decided to conform — until he got to Harvard.

It was there that the practical summers of his boyhood clashed most with the idea of conventional studies.

“He saw that people gave up their initiative as soon as they entered school,” said Jacobs of Fuller. “They are natural-born problem-solvers, up to the point we send them to school. They can ask big questions, and suddenly that all gets delegated to the teacher.”

Though he liked some of his Harvard professors, Fuller was the prototype of a restless, seeking, unconventional mind. That later made him wildly popular with counterculture audiences in the 1960s, including the young Jacobs, who said his own professors rarely embraced Fuller’s trademark attraction to the interdisciplinary. “In college,” said Jacobs, “people wake up from 12 years of [conventional] education, and begin to wonder: ‘Am I really studying what I want?’ ”

Leaving Harvard, Fuller resumed what he called “his real lessons.” He worked as a textile mill mechanic in Canada, hefted quarters of beef (and learned management) with meatpacker Armour and Co., and served as a line officer in the Navy — the ultimate classroom for a generalist interested in applied technology.

But Harvard gave Fuller a gift beyond academics, his biographers say: a lifelong preoccupation with human welfare, and the social, technical, and economic problems that vex the modern age.

Fuller believed that technology was part of the answer, and that Spaceship Earth could handle its human burden if the right solutions were in place.

During the turbulent 1960s, said Jacobs in a snippet of A.R.T. video about the play, “Bucky was kind of the calm at the eye of the hurricane,” a grandfatherly figure who acknowledged that the world had big problems, but none that couldn’t be solved.

“He was a great teacher, really, to the world,” said his daughter, Allegra Fuller Snyder, in the same video. The former UCLA dance and dance ethnology professor will be in Cambridge Jan. 16 for one of 12 public talks related to the play.

Others scheduled in the post-performance talk series Jan. 15 to Feb. 5 are: Amy C. Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at the Harvard Business School, who was once Fuller’s chief engineer (Jan. 20); Donald Ingber, director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, who discovered that living cells are structured according to the principles of Fuller’s “tensegrity architecture” (Jan. 25); the play’s production dramaturg Annie DiMario (Jan. 26 and 30); Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, who has written about Fuller (Jan. 29); and Derrah, who channels Fuller in the play (Feb. 5).

For more on the discussions, visit “Bucky and Me.”