Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff

A step in fight against tick-borne disease

New molecular method differentiates sexes, reveals whether females have mated

Ticks pose a grave risk to public health, with nearly half a million cases of the tick-borne Lyme disease treated every year in the United States.

Young nymph and adult female ticks typically pose the greatest risk for transmitting infection to humans. But, researchers say, there is much that is unknown about the sexual biology of ticks, knowledge that would prove useful in control efforts.

A new paper published in the Journal of Medical Entomology marks a major stride forward, chronicling a groundbreaking molecular method that differentiates male and female blacklegged ticks (commonly called deer ticks) and also reveals whether these arachnids have mated.

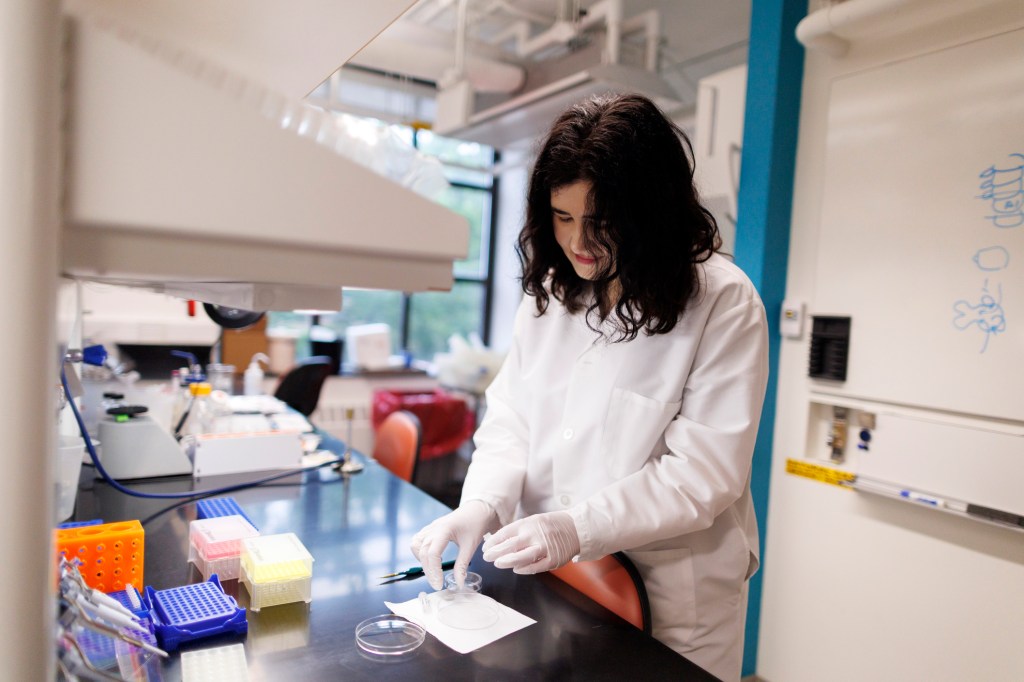

Lyme is perhaps the best-known disease passed by ticks, but the bacterium behind that malady is just one of several associated with them, explained Isobel Ronai, a Life Sciences Research Foundation Post-doctoral Fellow of HHMI in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and a primary author of the paper.

Citing other tick-borne diseases, such as babesiosis, Ronai pointed out that “ticks have a huge public health importance here in the United States in terms of the disease burden.”

“Ticks have a huge public health importance here in the United States in terms of the disease burden.”

Isobel Ronai

The risk, according to the Centers for Disease Control, is increasing.

“The number of cases of diseases transmitted by ticks and mosquitoes has increased significantly in the U.S. over the last 25 years, with tick-borne diseases now accounting for over 80 percent of all vector-borne disease cases reported each year,” said C. Ben Beard, principal deputy director of the CDC’s division of vector borne-diseases, who called for better “research aimed at better understanding tick reproductive biology.”

Ronai worked with her long-term collaborators at the University of Georgia, who had “a unique data set of tick genomes,” that is, the DNA sequence of blacklegged ticks from across the country. Together they developed a molecular test to determine whether individual ticks were male or female.

In addition to being able to sex the ticks, Ronai investigated “interesting results” in females collected in New York that had the marker for male DNA. By mating other ticks in the lab, she was able to determine that the marker could also be used to identify female ticks that had mated.

Ticks have a complex life cycle.

“They feed at multiple stages,” explained Ronai. “In mosquitoes only the adult stages take a blood meal, whereas in the ticks they feed at three stages throughout their life cycle.”

The ticks begin life as eggs, from which emerge larvae. Those larvae feed on a host before transitioning to their next stage, which is called a nymph. The nymphs also feed on a host.

“They take a blood meal and use that blood to progress to the adult stage,” Ronai said. “And then, at the adult stage, the female ticks feed to produce their egg clutch to start the next generation.”

“The overall sexual biology of the ticks is an area where we have a lot to learn at the molecular level.”

Isobel Ronai

Much is still unknown.

“I am very interested in our sexing assay being used to investigate whether there is any association between the sex of a larva or nymph and what hosts they’re feeding on,” said Ronai. From this behavior, we can determine “what potential microbes that cause disease male and female ticks are picking up from hosts and transmitting to humans.”

For her own research in the Extavour lab group at Harvard, the way forward is clear.

“I’m excited to explore what is happening with the biology at these immature stages,” said Ronai. “The overall sexual biology of the ticks is an area where we have a lot to learn at the molecular level.”

Then, added Ronai, “we can get to the stage of developing new control strategies for ticks that target them specifically.”