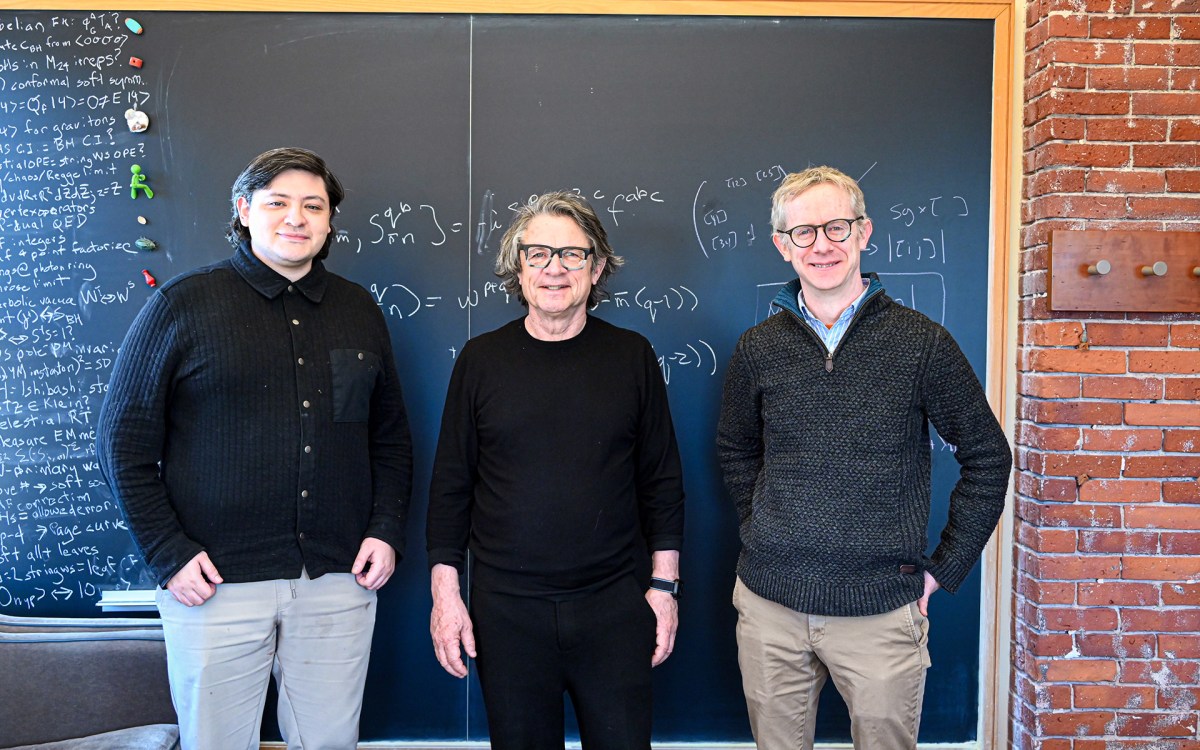

Dustin Tingley.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A common sense, win-win idea — and both right, left agree

Poll measures support for revenue-sharing plan on renewable energy that helps states, localities, and environment

Democrats and Republicans don’t see eye-to-eye on much. And they often don’t agree on various aspects of renewable energy. But a recent report finds there is one area in which they’re pretty much in sync: how certain national proceeds should be divvied up.

Results of a recent national poll shows most rank-and-file members of both parties think some revenue from renewable energy produced on federal land should go to states and local communities adjacent to these projects. Right now, it all goes to Washington, D.C.

“I figured that there would be bipartisan support just because of the way people talked about it, but I never expected those sorts of numbers.”

Dustin Tingley

The agreement surprised Dustin Tingley, the Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and deputy vice provost for advances in learning, who led the survey.

“I figured that there would be bipartisan support just because of the way people talked about it, but I never expected those sorts of numbers,” Tingley said. “It tells me there are a lot of very reasonable people, common-sense people, in both parties.”

The nationally representative survey of 2,000 Americans, conducted last spring, showed that 91 percent of Democrats and 87 percent of Republicans, along with 87 percent of Independents and 88 percent identifying as “other,” support distributing revenues from solar, wind, and other renewable energy projects sited on federal land to host states and the nearby communities most likely to be impacted by them.

Further, a large majority — 83 percent — said they believe renewables on federal lands have the potential to contribute to U.S. energy needs either “greatly,” or “somewhat.” The party breakdown of those responding “greatly” or “somewhat” was 93 percent Democrat, 72 percent Republican, 82 percent Independent, and 78 percent “other.”

The survey also contained questions about how such funding might be allocated, with respondents suggesting 21 percent to local governments, 27 percent to the federal government, 22 percent to the state, and 30 percent to ecological restoration.

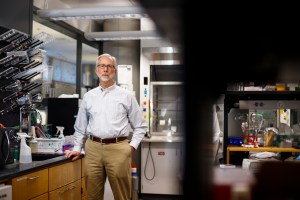

The results were published in a recent report, “Federal Land Leasing, Energy, and Local Public Finances,” written by Tingley and predoctoral research fellow Ana Martinez, with support from Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability’s Strengthening Community Cluster.

The poll responses reinforce the report’s contention that federal lawmakers should, in this case, do something that climate activists generally don’t recommend: follow the path forged by fossil fuels.

Some 30 percent of the country’s land area is owned and managed by the federal government, mostly the Bureau of Land Management. Coal, oil, and other fossil-fuel-extraction operations pay significant rent and royalties to the government: $7 billion in 2023. Federal law also requires revenue-sharing payments to state and county governments, which amounted to some $4 billion that year.

That money, Tingley said, provides critical support for public programs, including schools and county governments. With the exception of some offshore wind installations and the nation’s relatively few geothermal plants, revenue from renewable energy projects on federal lands goes directly to the U.S. Treasury.

As of April 2024, the report said, 41 wind, 53 solar, and 67 geothermal projects were permitted on public lands, which, when all are built, will generate 17.3 gigawatts of power, about enough to power 13 million homes. At the end of 2023, there were 150.5 GW of wind and 137.5 GW of solar in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

The different treatment of revenue-sharing between different types of energy generation makes no sense, either to Tingley or to many in the industry and in those nearby communities, said Tingley, who, in drafting the report, also conducted interviews with stakeholders.

“At first, honestly, I couldn’t believe it,” Tingley said about his reaction when he understood the discrepancy. “It’s just so odd. And no matter the angle — if I looked at it as if I’m the Biden administration or a Democrat, or as if I’m a Republican, I was left just puzzled about why it was set up this way.”

Tingley eventually gave up trying to figure out the logic and put it down to a quirk of recent political history. After all, when relevant legislation on solar and wind permitting was being drafted, the U.S. had little renewable energy, so it was a difference that perhaps didn’t matter much.

Today, the situation has changed. Many more wind and solar projects have gone up. And the prospect of getting a significant revenue share might generate local support for renewable power at a time when the nation’s plans to fight climate change demand an increase in installations.

Tingley pointed out that, though members of the two parties might align on this issue as a practical matter, the philosophy behind that agreement likely comes from different points of view.

“There are tons of renewables in Republican areas, and I think people there ask, ‘Why are we keeping all the money with the feds?’” Tingley said. “On the Democrat side, you’re trying to push renewables. And then there’s a common-sense, kind of ‘plain jeans’ feeling of ‘Why are we treating different types of energy differently to begin with?’”

Tingley said the agreement on the topic appears to extend from the grassroots to Congress, where proposals have been drafted on both sides of the aisle. Those proposals, however, have languished for reasons that are unclear. Any shift would take money from the federal budget, but the figures are small enough that they shouldn’t be deal-breakers, Tingley said.

In addition, he pointed out, passage of such legislation would signal to voters that Washington still can pass common-sense policies that benefit ordinary people and local communities, in this case those on the front lines of the energy transition.

“We’re not talking Wall Street; we’re talking Main Street and people living in rural areas,” Tingley said. “People on both sides, when presented with reasonable policy, will support it. There’s not enough of that being brought home by our elected officials because each side just wants to win for their own purposes rather than win for the American people.”