Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

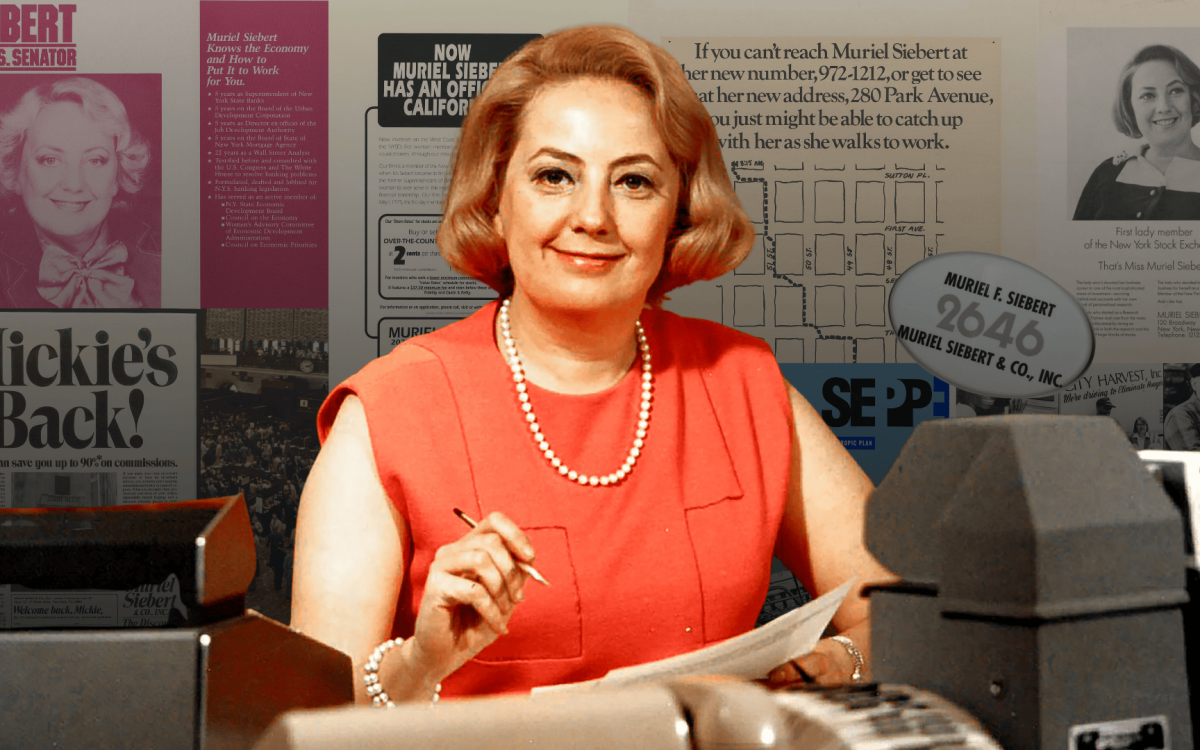

Studying ‘why women are interesting, and men are boring’

Nobel laureate Claudia Goldin recounts pioneering career spent tracing major part of U.S. workforce, economy hidden in plain sight

Part of the Experience series

Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

Raised in the Bronx by parents who placed high value on the sciences, Harvard’s newest Nobel laureate wanted to be a researcher from a young age. “Oddly, I thought of doctors as plumbers,” Claudia Goldin recalled. “I didn’t think of them as scientists, because the ones I experienced weren’t doing research.”

Pursuing that goal led Goldin to home in on economic history and, eventually, her prize-winning work on women’s labor force participation across the ages. As Goldin prepared for a trip to Stockholm, where she accepted the 2023 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences last month, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics sat down with the Gazette to reflect on her life and career trajectory. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

What were you planning to study when you started your undergrad at Cornell?

I was quite serious about bacteriology. But then I realized I didn’t know about many other fields, and I decided to do an exploration. I took an anthropology course. I took a lot of political science, a lot of history and economics.

And you fell in love with an economics course you took there.

It was a course with Alfred Kahn. I fell in love with the subject of industrial organization. I was excited by product markets. I also was interested in international trade. These are not subjects I do now.

What took you to the University of Chicago for graduate school?

I went to Chicago to study industrial organization with George Stigler and Sam Peltzman and Ron Coase. I thought I was going to do industrial organization, and maybe law and economics. I didn’t know anything about economic history.

When did you discover economic history and start studying with your mentor and fellow Nobel laureate Robert Fogel?

Economic history was a required course. In fact, I had to take two economic history courses. One of them was with Bob Fogel. I still know many people who were in that class and became economic historians. We had an incredibly good time modeling economic history and figuring out what sort of data we needed.

Economics today is more separated into those who do empirical work and those who do theory. Whereas when I was in graduate school, and even in the work I do now, the two are always linked. I think about an issue and figure out how best to model it before I figure out what sources I need to use.

Goldin as a graduate student in the early 1970s with fellow scholars including her mentor Nobel laureate Robert Fogel (facing her).

Courtesy of Claudia Goldin

Can you tell me a bit more about your experience at the University of Chicago, which was known for having female economics professors from an early date?

One has to understand that the field of economics in 1910 was very different from the field of economics in 1940 or 1970. The field of economics at the University of Chicago once included a group that, in 1920, became part of Chicago’s Department of Social Service Administration, and that included the prolific Edith Abbott [who earned her Ph.D. in 1905], who authored many lead articles in The Journal of Political Economy in the early 20th century that concerned social problems.

Some of this is in my book “Career and Family” (2021). I also discuss the economist Margaret Reid, who obtained her Ph.D. in 1931 and was tenured in the Economics Department — the real Chicago Economics Department. There was also a group of women faculty who preceded her, who were her teachers. Hazel Kyrk was Margaret’s mentor. She obtained her Ph.D. in Chicago in 1920.

If you look at the history of notable women, you’ll see that University of Chicago is high on the list of institutions where they did graduate work. Perhaps it was a more open institution. It was always coeducational, whereas East Coast universities were less so.

Did you feel the importance of this when you were there in the late 1960s and early ’70s?

Definitely not, because there were no women on the faculty then. I was one of two women in a class of about 45, 50 men. But that didn’t matter to me, because to a person on the faculty — Milton Friedman, Bob Fogel, Gary Becker, Ronald Coase, George Stigler; five Nobel Prize winners — nobody cared that I was a woman. All that they cared about was what I had to say, what I had to contribute.

“One knows there’s something interesting when you see a graph on women’s participation in the labor force that starts at 5 percent and goes up to 70 percent.”

Let’s talk about your work with Professor Fogel and the moment lightning struck concerning the importance of women’s employment as an area of study.

What it had to do with Bob was mainly encouragement. I was working on my dissertation, which became the book “Urban Slavery in the American South” (1976). Bob and Stan Engerman were working on a huge project called “Time on the Cross” on the economics of U.S. slavery, but I didn’t know that at the time.

Bob showed a huge interest in my work on urban slavery, probably because he was interested in something even bigger. I went to several archives in the South to dig up information for myself and for him. I also went to Utah to the big [Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints] archives.

I left Chicago in 1971 and finished my Ph.D. in ’72. Bob and Stan published “Time on the Cross” in 1974. I was, at the time, working in research areas that were historically close to the period of slavery. Many economic historians were interested in knowing what happened to Black Americans in the postbellum South and to the Southern economy.

In the meantime, Bob was enticed to leave Chicago and come to Harvard around 1975. But Bob decided to go to Cambridge, England, instead and needed someone to teach his classes at Harvard during the first year he was to be there.

I was a struggling assistant professor at Princeton when he asked me to come to Harvard as a visiting professor to teach his classes. I had just begun to work on why white women were not declaring occupations to census takers even if they were employed. Maybe they had a boarding house or took in laundry, but they did not list an occupation — whereas Black women did.

Then the late Harvard economics professor Marty Feldstein brought the National Bureau of Economic Research to Cambridge and put Bob in charge of a program called the Development of the American Economy. And then Bob decided to have a meeting to determine what researchers who were in the DAE group should be working on. We decided that I would continue my exploration, which I’d just begun, on the history of women in the labor force.

3 key Goldin studies

“Orchestrating Impartiality: The Effect of ‘Blind’ Auditions on Female Musicians” (2000)

Goldin and co-author Cecilia Rouse examined hiring data before and after the advent of “blind” auditions. They found the set-up increased the proportion of women in professional U.S. orchestras.

Illustrations by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

“The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions” (2002)

Goldin and co-author Lawrence F. Katz found oral contraception had enabled more women to invest in education while holding off on family formation.

“The U-Shaped Female Labor Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History” (1994)

Goldin traced the fall and subsequent rise of female labor force participation in dozens of countries as their economies advanced over two centuries.

What piqued your interest about this area of study?

One knows there’s something interesting when you see a graph on women’s participation in the labor force that starts at 5 percent and goes up to 70 percent. You have to ask: How did it get there? Why did it get there? I said this at the Nobel press conference: This is why women are interesting, and men are boring. Women had an enormously increased labor force participation rate. Their locus of employment and work changed.

Meanwhile, this area was opening up for lots of people, who were carving out different parts of it and informing me where I should look. It was pretty clear something important was happening in the early 20th century in the white-collar sector and with rise of clerical and office work.

And those changes were interacting with the history of education. I was interested in every single part of it: What was happening in manufacturing? How was technological change in manufacturing affecting work in general and women’s work in particular?

One is always motivated by one’s present. People in the 1970s were thinking about the issues of their day, which were occupational segregation and differences in earnings between men and women. What I realized is that we were talking about occupational segregation in the 1970s, but in fact, historically, there was industrial segregation.

There were entire industries — in the whole U.S. — that didn’t have any women employed in an industrial position. They were not laborers. They were not operatives. They were not managers. They were not anywhere. That was astounding.

“To a person on the faculty … five Nobel Prize winners — nobody cared that I was a woman. All that they cared about was what I had to say, what I had to contribute.”

Is there one finding from your research on women in the workforce that most surprised you?

There were tons! I later realized there were marriage bars [meaning single women were often fired when they got married and married women were not hired]. But when a set of laws disappears suddenly, nobody remembers they ever existed.

I was doing a project on the history of coeducation (2011). I thought, “This is going to be easy; this is a weekend’s work. I can just figure out when each school became coeducational.” Well, it turns out that few remember when their school became coeducational because institutions often don’t keep records.

On the day of your Nobel win, you talked about the importance in your career of working with other women. That surprised me because I imagined you being the only woman in the room at so many points, having been the first woman to receive tenure in the economics departments at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard.

When I first began, I had a co-author named Frank Lewis [a former student of Stan Engerman’s at the University of Rochester who went on to become a professor at Queen’s University]. I worked with Kenneth Sokoloff, also a student of Bob Fogel. And I had a number of other co-authors, mainly men.

The first woman with whom I wrote a paper was Elyce Rotella [now a lecturer at the University of Michigan] and her now husband, George Alter [professor emeritus at the University of Michigan]. We worked on banking records and the savings of ordinary Americans (1994). Elyce had done insightful work on women’s employment as a graduate student. But there were fewer women for me to work with until much later.

But then when I was hired by Harvard, the number of women in the field began to increase. Cecilia Rouse [now president of the Brookings Institution] and I worked together on the orchestra project (2000). I later met Claudia Olivetti [now an economics professor at Dartmouth]. We’ve been close friends, colleagues, and co-authors now for quite some time.

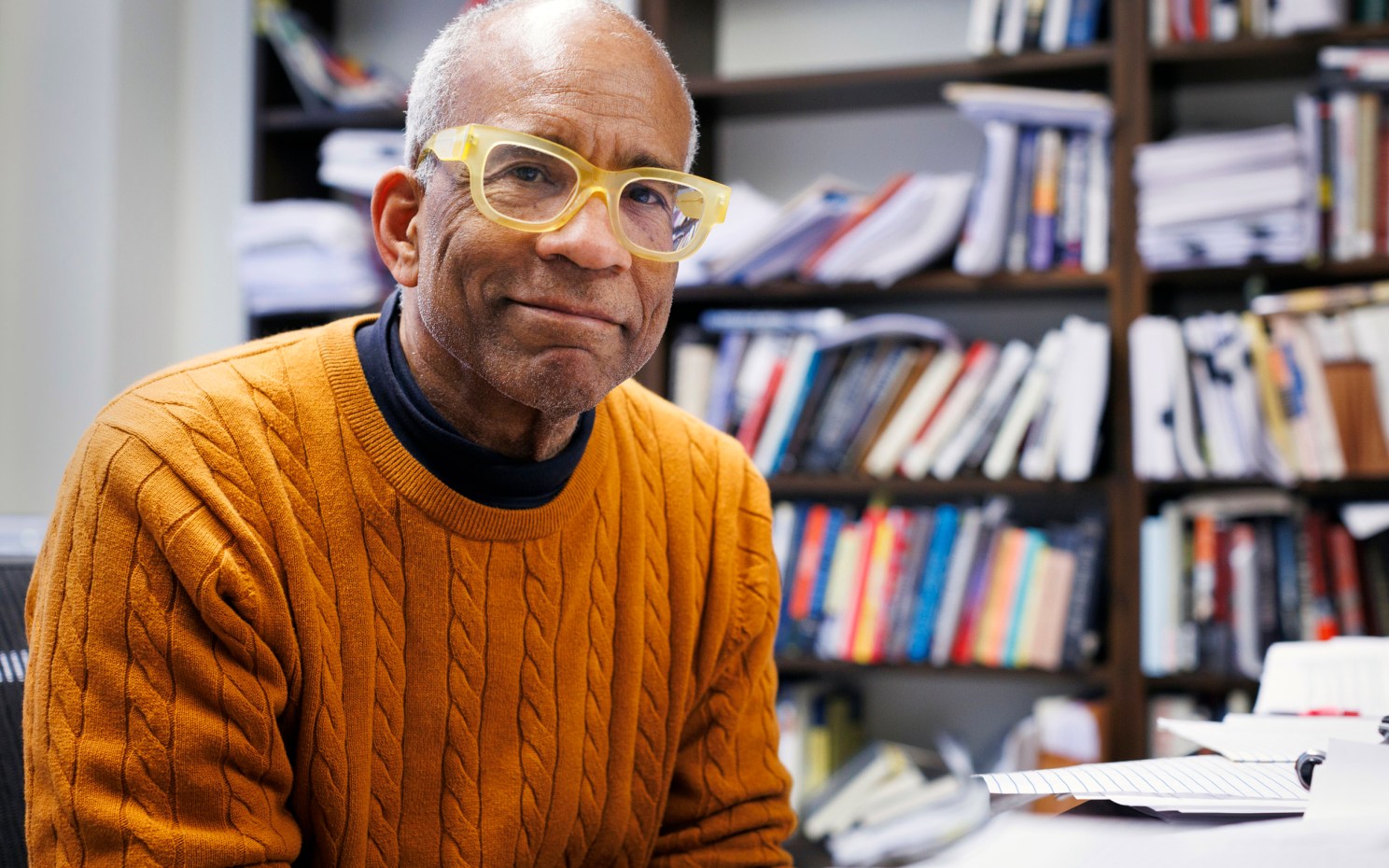

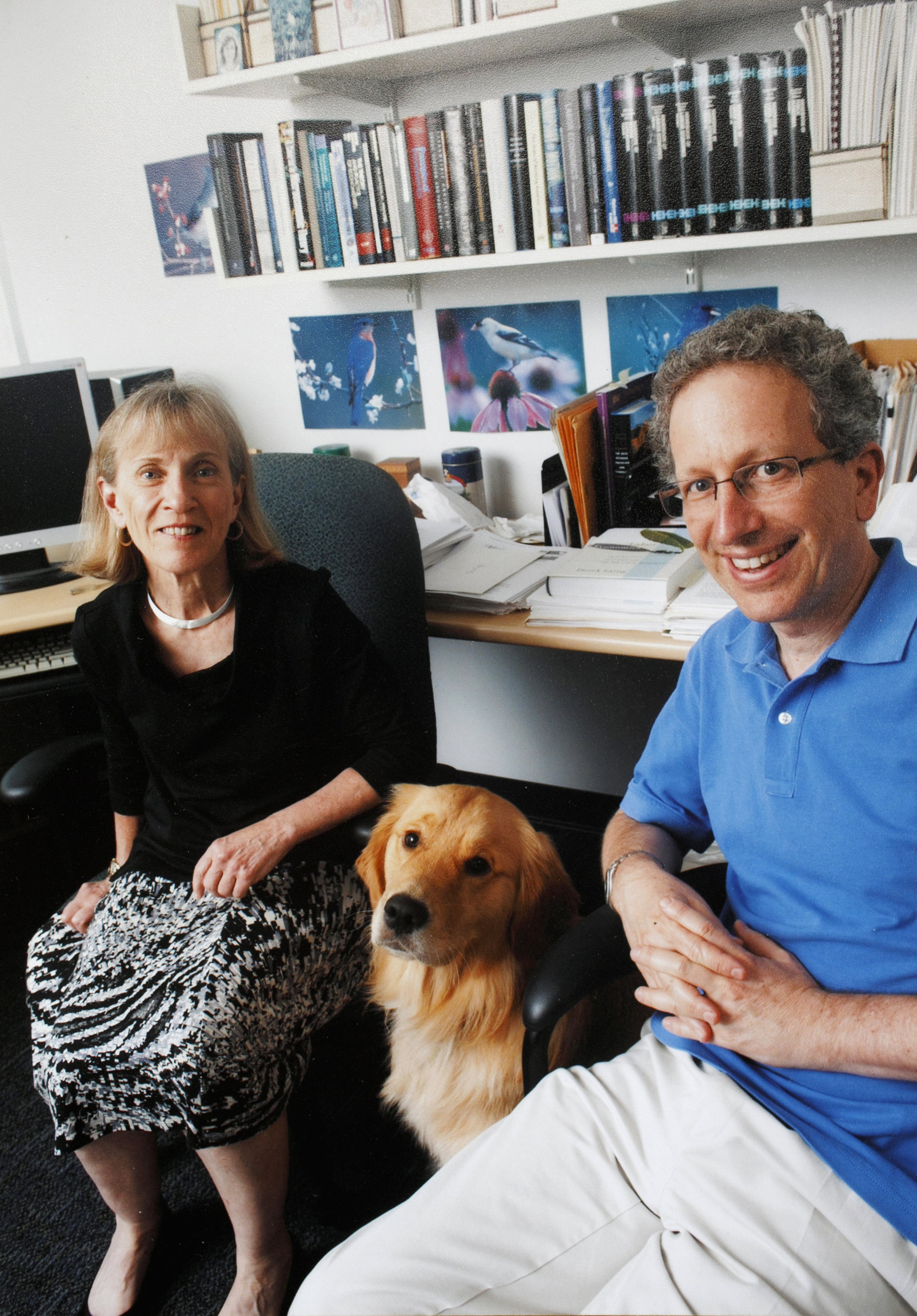

You have also collaborated a good bit with your husband, Lawrence Katz, who is also a professor in Harvard’s economics department.

We did the birth control paper (2002) and researched many others on economic inequality. It all began around 1991 or ’92. He was working as the chief economist in the Labor Department, and I was at the Brookings Institution. I had just finished the book “Understanding the Gender Gap” (1990) and was working on the history of education in the U.S. and inequality in earnings.

Ever since the 1980s, Larry had noted: “Inequality is rising; let’s analyze why.” We realized then that our work could be complementary. He was working on the present. I was working on the past. We could put those two together.

Circa 2005 with husband Lawrence Katz and Prairie, one of three golden retrievers Goldin has adopted and trained over the years.

Courtesy of Claudia Goldin

How did you meet?

In part because of [the late Princeton University economist and former Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy] Alan Krueger, but in part because the field of economics isn’t that big.

When were you married?

I purchased a home in 1991. We lived in the home for many years, and all that time my friend who was a township judge in New York kept saying, “Come here and I’ll marry you.”

But you can’t really do that, because you have to fill out the forms the day before the civil ceremony. Finally, one day — I think it was in 2017 — I decided that would be a good thing to do. Larry was in New York City and took the train to Rhinebeck, close to where she lived. I drove there and filled out the forms the day before. And she married us.

And then, when I got my taxes, I realized how stupid that was. [Laughs.]

In presenting your award, a member of the Nobel prize committee talked about your work as a “data detective.”

Some time ago, I was asked to write an autobiographical statement. I told the person who asked, “I will do it only if it writes itself.” So I sat down and I started writing about my life as a detective. It’s called, “The Economist as Detective” (1999). It did write itself.

Harvard University

Is there a favorite data set that you’ve unearthed?

There are tons and tons! The U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau, which was founded during World War I, executed an immense number of excellent surveys. I would go to the National Archives in D.C. and figure out which boxes had the Women’s Bureau bulletins, hoping that in the boxes would be the actual survey forms. I could see that if there were enough boxes, they might have the surveys. If there were few, they probably only had bureaucratic administrative material.

One of my favorites is the “1940 Clerical Workers Survey,” which was done in 1939. It asked firms very ordinary questions, since the Women’s Bureau was interested in the impact of machinery on clerical workers.

But then it also had questions like: “Do you hire married women?” “Do you fire a woman in your employ if she gets married?” “What occupations are open to women only?” “What occupations are open to men only?” And my favorite is, “What policies do you have with reference to race and ethnicity?” In the absence of anti-discrimination laws, firms were amazingly candid. That evidence from these surveys became important in some of the work I did.

Of course, there’s also the work Cecilia Rouse and I did on blind auditions, for which we went from orchestra to orchestra. We went to Detroit, for example. They didn’t have a true archive the way the New York Philharmonic did, or the BSO; they just had a lot of boxes. They told us: “Just go look at the boxes.”

“I want to encourage Harvard students to think independently … to realize that questions don’t have answers that are yes or no. Sometimes the answer isn’t really an answer.”

You have a reputation for being very committed to your students. One of your colleagues shared that you were at the department offices in Littauer Center late into the evening on the day of your Nobel win, because you were keeping previously scheduled meetings with them. Can you share something of your philosophy about teaching and mentoring?

Larry and I are in charge of job placement. I actually met with 10 of those students after the press conference. I can’t say I have a philosophy. My sense about teaching is that I teach when I have something to offer, something that I think is useful. And if my students don’t understand it, that’s my fault.

The other part is that I want to encourage Harvard students to think independently and to think of questions from first principles. I want them to realize that questions don’t have answers that are yes or no. Sometimes the answer isn’t really an answer. The whole purpose of asking the question is to go on that trip to try to figure out how you would answer it.

Your latest paper, “Why Women Won” (2023), traces the expansion of women’s rights since suffrage. What inspired you to tackle this topic?

I was visited last summer by an amazing innovator and entrepreneur from Korea. Very quickly I realized that she had a story to tell about a country that developed remarkably fast, one of the fastest of any country in the world. Generations that had almost no education and lived in rural villages had children who had college degrees and lived in Seoul. The culture clash in this type of society is enormous.

She wanted to know why is it that in Korea, judges are so mean and nasty to women, particularly those who are getting divorced. Legal rights that seem to exist on paper are being abrogated by a group of judges who are representing the old Korea. She wanted to know what she could do about this.

And I thought, “I don’t know because I don’t even know all of the legal rights that exist here.” I really didn’t know the case history, the legislative history, the federal and state history. I didn’t even understand when all this began and why it began.

I decided I would work on it. I have here two folders; one says “literature, Korea” and the other “literature, U.S.” I immediately got in touch with my friends in Korea and told them to send me anything that would be useful. Then I realized what I really needed to work on is the U.S.

And as I worked on the U.S., I realized that much of the history really hadn’t been told in a linear, continuous manner. It’s really a history in which there were many fortuitous accidents concerning the relationship between the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement.

As we talk, your golden retriever Pika, who also was there at the Nobel press conference, is here in your office with us. Can you tell me about him?

I got Pika 13 years ago. Prior to getting him, I realized I wanted to do some serious dog training. Until he was eight, he was a titled scenter.

How many golden retrievers have you adopted and trained over the years?

Three. The first one was Kelso, the dog I got in graduate school. She was an extraordinary dog, but I wasn’t an extraordinary trainer. She was the dog I had when I was an assistant professor at Princeton, when I was at Penn in the 1980s, when I came here in 1975. She would have been a great training dog, but I didn’t have the time or the wherewithal to do it. She died when she was almost 16. I couldn’t even look at another dog; I was so attached to her.

And then finally we got another dog named Prairie, who died at age 7½ of cancer. I had been training her, so she was my first real obedience dog.

Around the age of 2 near her family apartment in Parkchester, New York, wearing a jacket made by her paternal grandfather, a “master tailor.”

Courtesy of Claudia Goldin

Did you have dogs as a child in the Bronx?

I grew up in Parkchester, and it did not allow any animals, other than birds and goldfish. It was a fascistic community. It didn’t allow air conditioning units. It didn’t allow washing machines. I never even saw a bicycle.

Tell me about the two large photos on your office wall.

They’re from the American Memory collection of the Library of Congress, which contains various collections of stereoscopic prints. These were popular around 1910, 1920. The two in my office were done a bit later. The older stereoscopic prints are fascinating because they tell the story of small-town America. Most of them were done by setting up three cameras in the crossroads of a town. You can see what the cars looked like, what the horses looked like, what the businesses looked like.

I would spend a lot of time as a historian just looking at them and getting a sense of things. When I wanted to get photographs for an office some time ago, I picked two from a related collection [“Taking the Long View”] that meant the most to me. The top one is New York City in 1931 at the completion of two amazing buildings: the Chrysler Building to the right, the Empire State building to the left. The bottom one is Mount Rainier in 1925 before they asphalted many of the trails at the base.

I get why New York is meaningful to you, but why Mount Rainier?

Because those are the mountains I love. I love the Pacific Northwest.

Do you visit there often?

I used to. I can’t go now because of the dog — and hiking without the dog wouldn’t be as much fun. But I’ve hiked the northern Cascades, the Alpine Lakes region, Mount Shuksan, Mount Baker, Mount Rainier. I’ve even dragged Larry there. He was not a happy camper, but he loved hiking and birdwatching. [Laughs]

Who will accompany you to the Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm?

Larry will go with me, and I invited some friends. I told you about my early co-authors Elyce Rotella and George Alter — I invited them in part because I love them, and in part because 25 years ago, Elyce and George were in Stockholm and she wrote a report for the CSWEP newsletter, which is a little publication of the American Economic Association Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession.

[Goldin picks up her phone to read a text verbatim.] The last line of her report said, “I will remember attending the Nobel Prize ceremony. This is one of the highlights of my year in Sweden. It was a good show. And I hope to attend again someday. The next time, however, I hope that some of the winners and presenters are women.”

I wrote to her: “Do you really want to travel to Sweden this December? Just let me know. One of the winners and presenters is a woman.”