A Salata Institute project led by Elaine Buckberg targets a major obstacle to widespread electric vehicle adoption.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

On the road to smoother EV charging — and hopefully, greater adoption

New Salata-led program with Harvard, MIT researchers aims to grow, improve infrastructure for longer trips, those who can’t charge at home

It was the perfect way to kick off her work at the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability.

Elaine Buckberg, former chief economist for General Motors, drove from Michigan to her new home state of Massachusetts this summer in her EV and found one aspect of the journey particularly challenging.

“If you’re going through a part of America that doesn’t have a lot of chargers, you really need to be researching,” said Buckberg, who made the trip a second time in another EV she owns with her husband. “Is that charger going to work when we get there? What’s our fallback option? Do we need to charge sooner?”

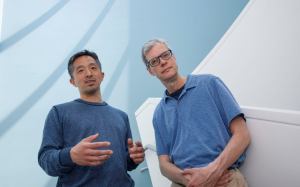

That scarcity of public chargers, with unreliable coverage for long-distance trips, remains a major obstacle to widespread EV adoption. As head of the new Driving Toward Seamless Public EV Charging initiative, Buckberg, a new senior fellow at the Salata Institute, will lead a team of researchers from Harvard and the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research in pursuit of improvements. Key collaborators include Christopher R. Knittel, an MIT applied economics professor who also directs the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, and Harvard’s Vice President for Climate and Sustainability James H. Stock, who also directs the Salata Institute.

Buckberg previewed some of the team’s ideas for the Gazette while also offering tips for EV drivers. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

Elaine Buckberg

GAZETTE: Why is the EV transition so important?

BUCKBERG: Transportation accounts for 28 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Light-duty vehicles, like passenger vehicles, account for 17 percent. Transitioning to EVs is tremendously important for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and continuing to drive emissions lower to ultimately net zero.

GAZETTE: How do problems with public charging hold back EV adoption?

BUCKBERG: The fact is, EVs are becoming increasingly good substitutes for internal combustion engine vehicles. They have longer ranges. Their price point has come down. They are becoming available in different shapes and sizes. But the thing that’s not getting solved is access to ubiquitous and easy charging. It’s a piece that won’t be resolved by the automakers alone.

A lot of early EV adopters have homes where they can install charging, but to actually achieve the EV transition we need two things. One, we need communities and workplaces to provide EV charging options for people who can’t plug in at home. Second, we need DC fast charging along highway corridors so every EV owner feels like they can do a road trip.

That’s important because market research shows that auto buyers buy cars for their extreme use case. Even if there are two cars in the household and they do very few road trips, they still don’t want a car that will not do that road trip.

BUCKBERG: The first project we’re looking at is real-time sharing of public charger data. So you could go on the likes of Apple or Google Maps, just like you already do when planning your trip, and find chargers along the way, know whether they’re operating, know whether there’s a queue, and know what the price is in advance.

Another thing we’re thinking about is zoning that would drive investment in community charging locations. That might include developing zoning best practices and using the resources of Harvard — like the Taubman Center for State and Local Government and Bloomberg Center for Cities — to roll these out to municipalities. For example, you need a charger for every X spaces in your parking lot if that lot is for public, employee, customer, or resident parking.

One more important consideration with EVs is maximizing climate benefits. You actually want to drive charging toward the daytime, when more renewables are involved in producing the electricity to charge vehicles, meaning lower emissions. We have to think about how electricity rate structures are designed.

GAZETTE: How did you make it work during your own cross-country trips?

BUCKBERG: It turned into my husband driving while I feverishly researched. The app native to my Chevy Bolt EV allows you to read your level of charge when you start the trip. But then it’ll say, “Stop at this charger” in some smaller town in upstate New York.

I then needed to try to find information on the internet about whether that charger was working. Does this type of charger have a website? Can I cross-reference that with another site that has user reporting on whether chargers are working or not, like Plugshare?

Do one of these sites tell me when someone last used it? If it worked during the last 12 to 24 hours, I feel pretty good. But if I can’t find a report of it working in the last few days, I’m going to be much more cautious. On our second trip, we stopped at a charger that had worked for us two weeks earlier. And this time it didn’t work.

GAZETTE: Where do you see progress on EV charging?

BUCKBERG: A consortium of seven automakers just announced a joint investment in 30,000 chargers in North America. And they want them in places with restaurants and bathrooms. Other companies are making moves to install chargers in places where it wouldn’t be so bad to charge for 20 or 30 minutes, like truck stops and the parking lots of big box stores. You could plan your lunch or errands around them.

But, despite this progress, we need the EV charging experience to get much better. We need lots of chargers at each station. We need vehicles to have built-in software that plans your route. Your EV should send you to the charger and precondition the battery without your asking. We need every EV owner to have this kind of experience. For that to happen, EV charging infrastructure needs to get much better much faster. That’s why this collaboration with MIT is really important.