You bought an electric car. Why did your carbon footprint grow?

It may sound counterintuitive but you probably don’t drive enough, says grad’s research

As a sophomore, Lucas Woodley ’23 started asking tough questions about electric vehicles. Are tax credits effective at reducing carbon emissions? If not, how might incentives be improved for greater social benefit?

“I wanted to understand how different driving behaviors would impact the EV’s ability to reduce emissions,” said the recent College graduate. “We know EVs deliver environmental advantages under the right conditions, but what exactly are those conditions?”

Over the next 2½ years, Woodley, who concentrated in economics and psychology, went deep on these issues, both independently and with lecturer Ashley Nunes, a senior research associate at Harvard Law School and an associate in the Economics Department. The resulting body of research examines how public dollars are spent on electric cars.

“If you’re someone who seldom drives, and the vehicle is mostly going to sit in the garage, then you may counterintuitively be better off owning a gasoline-powered vehicle.”

Courtesy of Lucas Woodley

Woodley’s first big research project, published last year in Nature Sustainability with Nunes as lead author, found EV buying incentives often fail to deliver on the government’s investment. Not only do U.S. subsidies flow to the well-off, with new EVs still averaging nearly $12,000 more per vehicle in 2022 than those powered by fossil fuels, but it turns out tax credits (up to $7,500 in 2023) can incentivize the wrong buyers. Many are led to increase their carbon footprint.

“If you’re somebody who drives a fair amount then you are likely well-suited to drive an electric vehicle,” Woodley said. “If, on the other hand, you’re someone who seldom drives, and the vehicle is mostly going to sit in the garage, then you may counterintuitively be better off owning a gasoline-powered vehicle.”

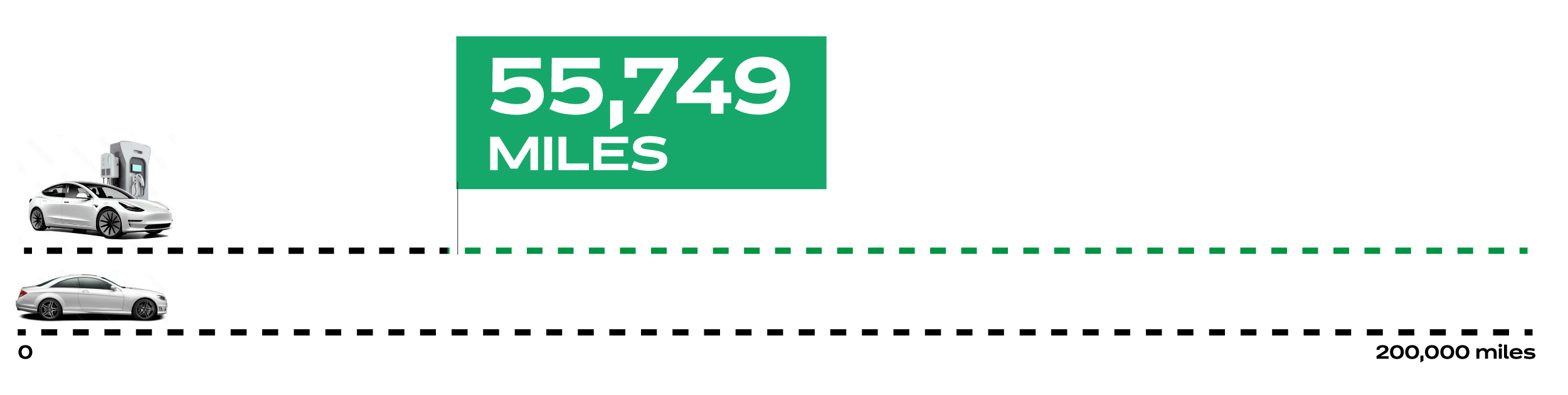

This is because the batteries that power EVs are responsible for an outsize share of emissions during the manufacturing process. Because EVs are dirtier to build but cleaner to drive, Woodley explained, they must meet certain mileage thresholds before environmental advantages are realized. In the U.S., the typical non-luxury EV needs to log between 28,069 and 68,160 miles before netting any emissions benefits.

“However, many households sell their vehicle before they get there,” he said.

Tax credits, the researchers concluded, should incentivize long-term use of individual EVs. Furthermore, low- and middle-income buyers are, on average, better positioned to realize the emissions advantages of EV drivership (that is, they log more miles relative to the number of cars they own). In April 2022, just after their paper was published, Woodley and Nunes put out a policy memo that recommended extending procurement incentives to the secondhand market. Within days, the Biden Administration announced tax credits for used EVs (up to $4,000 in 2023) as part of the Inflation Reduction Act.

“I wouldn’t be so arrogant as to assume it was because of our work,” Woodley said. “But it was great to see some of our policy recommendations reflected.”

As of 2022, Woodley’s research showed that aggregate use of EVs below 55,749 miles may — in the U.S., at least — fail to generate any emissions benefit over gas-powered vehicles.

Source: “Targeted Electric Vehicle Procurement Incentives Facilitate Efficient Abatement Cost Outcomes”

Woodley made a quick impression on his thesis advisor, Vice Provost for Climate and Sustainability James Stock. “Lucas certainly asks a lot of interesting questions,” said Stock, who is also Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor of Political Economy.

Woodley used his thesis to investigate the economic impact of the very tax credits for which he and Nunes had advocated. In the end, Woodley concluded that most of the value of used EV tax credits accrued to individuals selling their cars, Stock explained.

“Lucas started off in a different place, with the much more conventional view that tax credits would benefit people with lower incomes. After a lot of hard work and analysis, he had quite a different conclusion.”

As Woodley grew in his writing and analytical skills, Nunes encouraged him to take more ownership in subsequent research. The 22-year-old served as lead author on their next paper, published last spring in Sustainable Cities and Society and filled with ideas on optimizing government spending on EV incentives. One suggestion involved subsidizing EVs for workers who put in long miles, including rideshare drivers who average 160 to 200 miles per day. After all, the researchers found too many EVs are purchased as second cars, only to sit unused.

Woodley later presented these findings with Nunes at a National Bureau of Economic Research conference.

This fall, when he enters Harvard’s Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences to pursue a Ph.D. in psychology, Woodley will turn his focus to another long-time research interest — intergroup conflict resolution — with Professor Joshua Greene. But first, Woodley has more research to finalize with Nunes, including a paper (still under review) centered on his analysis of EV emissions benefits in all 50 states, given how the country’s patchwork of electricity grids incorporates varying rates of green energy. Among the questions they are asking: In what states do investment in EVs do the least good? And how do the emissions benefits of EVs compare to that of hybrids?

The goal is not to discourage EV ownership, Woodley said, but to improve policymaking and maximize emissions reduction per public dollar spent. “Like a lot of people my age, I’m concerned about climate change,” he said. “For me, there’s always the question of how to improve environmental sustainability while recognizing the associated political and financial realities.”