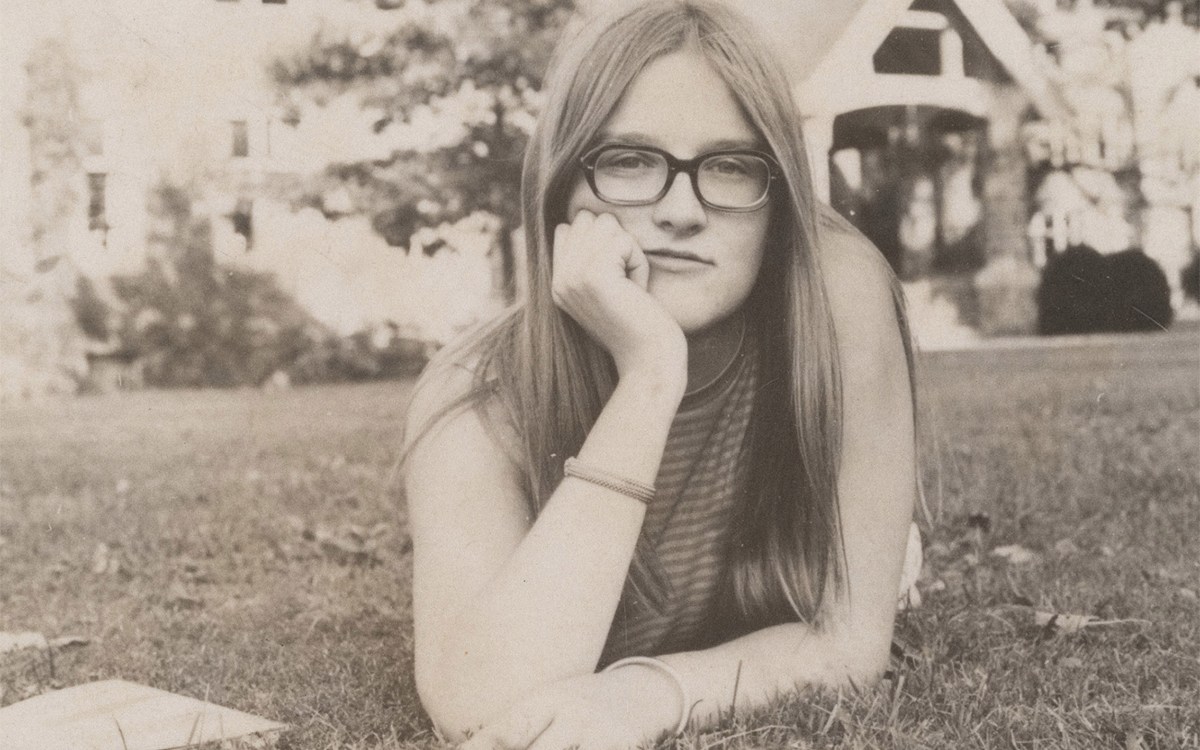

“I wanted to tell a story about a particular time in our American experience and a particular time in my life,” said Drew Faust of new memoir.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Living witness’ to a country’s turbulent progress

Drew Gilpin Faust on the spark behind ‘Necessary Trouble’ and the political engagement the memoir revisits: ‘It was a way for me to survive in a world in which otherwise I would be so constrained and morally compromised.’

More like this

Drew Gilpin Faust was only 9 years old, but her message to the president of the United States demonstrated a mature sense of justice.

“Please Mr. Eisenhower,” she wrote in 1957, “please try and have schools and other things accept colored people.”

Decades later, the historian had only vague memories of her youthful dispatch. While researching letters Confederate women wrote to their president, Jefferson Davis, for the 1996 Civil War book “Mothers of Invention,” it occurred to Faust that her own message had likely been preserved, prompting her to seek it out from the Eisenhower Presidential Library. The tidy lettering and creased pages serve as the frontispiece of “Necessary Trouble,” a new memoir detailing Faust’s coming-of-age amid the transformations of mid-century America.

“I was moved to write the book by an increasing recognition that the ’50s and even the ’60s have become a kind of alien land for most people living today,” said Faust, president emerita of Harvard and the Arthur Kingsley Porter Research professor.

She saw in the project an opportunity to serve as “living witness” to a vastly different time. “I wanted to tell a story with a sense of progress, in a way the much-maligned Baby Boomers could take pride in,” added Faust, who also served as founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. “Because there was an awful lot about our younger years that was not just unimaginable for a girl or a person of color; it was intolerable.”

“From the time that I was a small child, I was focused on what was fair and what wasn’t.”

Drew Gilpin Faust

The memoir charts Faust’s escape from the conservative strictures of her privileged Virginia upbringing. Her letter to Eisenhower becomes all the more dramatic when viewed alongside family history. Of particular note is the plaque her paternal grandmother, Isabella Tyson Gilpin, arranged for installation in a local cemetery, also in 1957. It commemorates “the many personal servants” buried at the site before 1865, laid to rest by their “friends and masters” with “affection and gratitude.”

“It was a kind of ‘Gone With the Wind’ approach to slavery and race relations,” Faust observed.

Also resurfaced for the book are the wartime experiences of family members, including the 1918 death of her aviator great-uncle. “The impact of the First and Second World War on marriage and family structures is something I inherited,” Faust shared. “They form almost a triad with the Vietnam War, which plays a large role in my life as I become a student-activist.”

As Faust travels back in time, readers meet a child with a sharp antenna for world events: the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, Hungary’s ’56 Revolution, the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik. The girl who would become Harvard’s first female president bristled at her mother’s traditional notions of feminine propriety. Her sense of moral clarity, so evident in the Eisenhower letter, sprung directly from the limitations that were foisted upon her, Faust says.

“From the time that I was a small child, I was focused on what was fair and what wasn’t,” she said. “Because I had three brothers, I was constantly being told I couldn’t do this or that because I was a girl. And that was infuriating.”

Faust would plunge herself into the Civil Rights Movement, culminating in 1965 when she marched with thousands of nonviolent demonstrators from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. As a Bryn Mawr undergraduate, she joined anti-war protests and challenged the era’s lopsided restrictions on the lives of young women. The point of writing a book wasn’t to tout these contributions, which Faust characterized as “mild” in an interview, but to capture the urgency she felt in challenging the status quo.

“I try to cast my engagements in the era’s politics and social change as necessary for me,” she said. “It was a way for me to survive in a world in which otherwise I would be so constrained and morally compromised.”

As for the book’s title, the Georgia congressman and Civil Rights icon John Lewis frequently spoke of the “necessary trouble” needed to advance racial equality. For Faust, he had been “a hero from afar” until they became friends during her presidential tenure in Massachusetts Hall. She later invited Lewis to deliver the principal address at her final Commencement as Harvard president in 2018.

As she got to work on the memoir, it struck Faust that Lewis’s phrase was “the perfect encapsulation of what I wanted to say.” In an epilogue, she recounts approaching Lewis just months before his death to seek his blessing for the title. “I do so as a gesture of respect and tribute to a man who inspired me from the era of the Freedom Rides to the confrontations of Lafayette Square and the emergence of Black Lives Matter,” Faust writes.

Her story ends amid the tribulations and violence of 1968, the year both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated against the backdrop of devastating losses in Vietnam. It was also the year Faust earned her bachelor’s degree, voted in her first presidential election, and accepted her first full-time job.

There will be no follow-up recounting her decades as a University of Pennsylvania professor or her 11 years leading Harvard. “I wanted to tell a story about a particular time in our American experience and a particular time in my life,” Faust said. “This is it for me and memoir.”