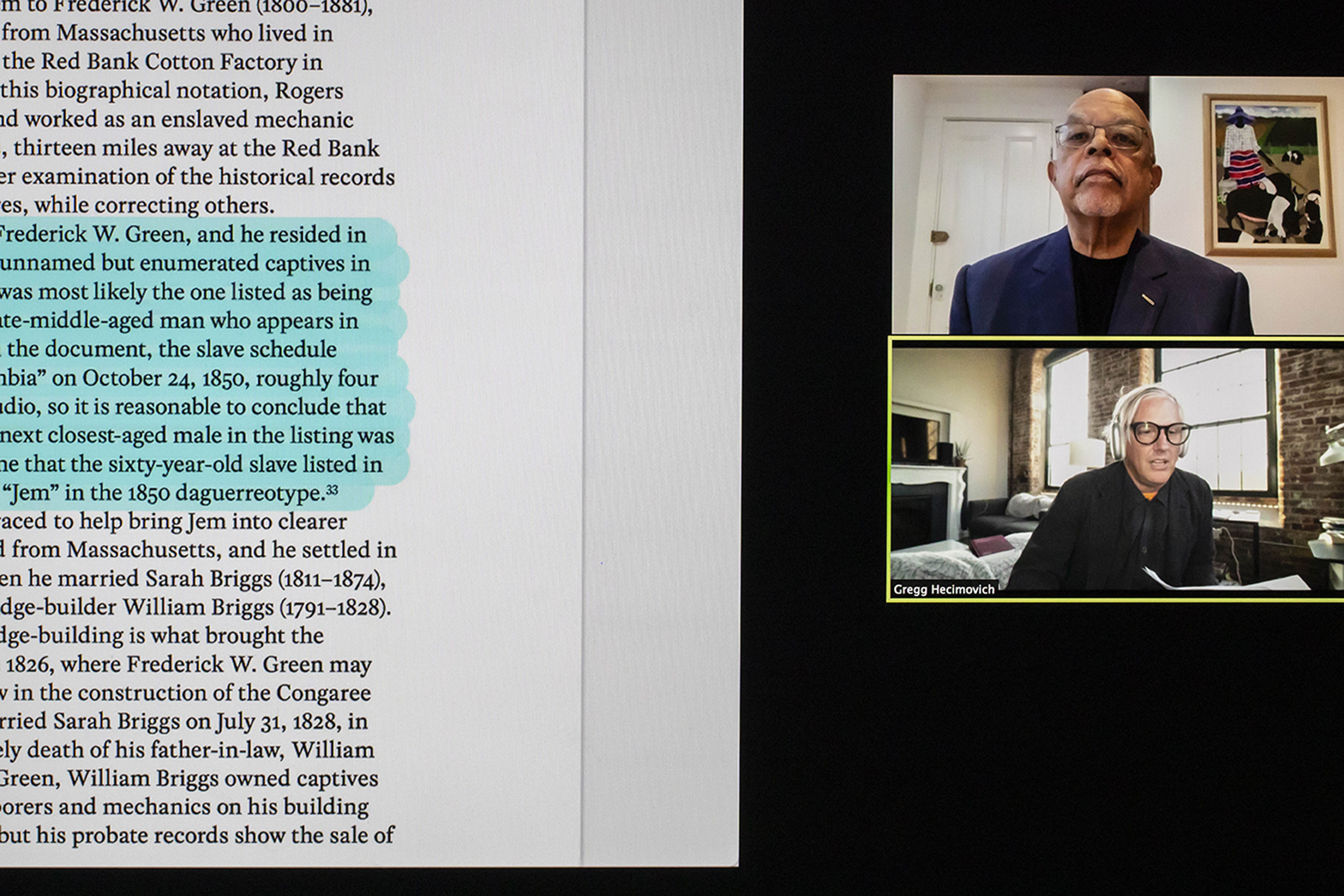

Henry Louis Gates Jr. (top) and Gregg Hecimovich discuss the recovery of the life stories of the slaves in the Zealy daguerreotypes. Shown is a page from the chapter Hecimovich wrote for the book “To Make Their Own Way in the World.”

Recovering the life stories of the Zealy daguerreotype subjects

Scholars dig into the legal, business records of owners of the enslaved for clues

The disturbing nature of the Zealy daguerreotypes, depicting enslaved Africans in 19th-century America, stems in part from the treatment of their subjects. In these images, commissioned by Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz and currently housed at the Peabody Museum, the slaves are robbed of their life stories as well as their basic humanity.

Gregg Hecimovich, a Furman University English professor, is among the scholars who has been working to recover those stories. On April 7 he met via Zoom with Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, and discussed the research that informed his chapter in the recent book “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,” co-published by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and the Aperture Foundation.

The daguerreotypes preserve only the names given to the subjects: Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, Fassena, Drana, and Jack. As Hecimovich explained, anything else about their identities had to be uncovered by careful research. And Gates pointed out the unfortunate paradox — in order to recover the histories of the enslaved, one first has to research the white Americans who enslaved them. Only six counties recorded slaves’ names in the federal Census, he said, but they were identified by name among holdings in estate records and wills.

Asked by Gates to outline the mechanics of his research, Hecimovich explained how he learned more about Jem. Because his owner, Frederick W. Green, was named on the daguerreotype, he was able to look into archives in Columbia, S.C. Only one slave in the records was listed as being in late middle age — most likely Jem, given his appearance in the image.

Further research revealed that the 60-year-old had been part of a work gang that did major construction in downtown Columbia, including building racetracks and canal projects. “Someone like Jem helped build Columbia, and I find that powerfully moving. He’s not a victim stripped for a photograph that is going to prove the incapacity of Black people. He is the labor and the strength that produced Columbia.”

Not every story was as easy to reconstruct, Hecimovich said. While he found other slaves from the Zealy collection in probate records, Drana proved elusive. It’s known that her owners did transfer slaves later in her life, but it’s not known whether Drana escaped or was sold. Still, he said he brings his students to the spot, now under a parking lot, where she may have been buried. “Like every figure who was photographed, I want to let them speak, as they do so vividly when you look at these daguerreotypes.”

Gates said trying to reconstruct life stories was complicated by the fact that some of the information passed down about the Zealy subjects wasn’t correct. Agassiz, for instance, made assumptions about their places of origin based solely on their looks.

“Those African ethnic identifiers just leapt from the brain of Louis Agassiz, who decided that he knew just by looking at a person of African descent from whence they had originated. It’s completely arbitrary. What the hell did he know about Africa?” In fact Hecimovich said that Agassiz wrote in a letter that Jack had tried to correct him about where he was from, but the professor refused to accept it.

Gates noted that some of his own family history has lately been recovered, thanks to the genealogical work of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He recalled that as a child he was shown the obituary of his great-great grandfather, and that, “This was the first time I learned what the word ‘estimable’ meant.”

Yet as an adult he could never prove that the obituary existed. “I started thinking that maybe I’d made it up,” he said. Only last year, when he was about to address the RootsTech conference in Salt Lake City, did he contact one of the researchers in Provo and was then sent the newly digitized obituary. “So my point is that you always have to go to the metaphorical Columbia. There are things you just can’t find online.”