How the Black Church saved Black America

Photo by Jack Delano/Creative Commons

Henry Louis Gates’ new book traces the institution’s role in history, politics, and culture

Excerpted from “The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song” by Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Penguin Press)

Political activists — including Malcolm X, of course, but especially the Black Panther Party in the latter half of the 1960s — have debated whether the role of the Black embrace of Christianity under slavery was a positive or negative force. There were those who argued that the Black Church was an example of Karl Marx’s famous indictment of religion as “the opium of the people” because it gave to the oppressed false comfort and hope, obscuring the causes of their oppression and reducing their urge to overturn that oppression. But I do not believe that religion functioned in this simple fashion in the history of Black people in this country.

As a matter of fact, although Marx was no fan of religion, to put it mildly, this statement, which the Panthers loved to quote, was part of a more complicated assessment of the nature and function of religion. The full quote bears repeating: “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.” Marx could not imagine the complexity of the Black Church, even if the Black Church could imagine him — could imagine those who lacked the tools to see beyond its surface levels of meaning. James Weldon Johnson, in his lovely poem about the anonymous authors of the sacred vernacular tradition, “O Black and Unknown Bards,” put this failure of interpretive reciprocity in this memorable way:

What merely living clod, what captive thing,

Could up toward God through all its darkness grope,

And find within its deadened heart to sing

These songs of sorrow, love and faith, and hope?

How did it catch that subtle undertone,

That note in music heard not with the ears?

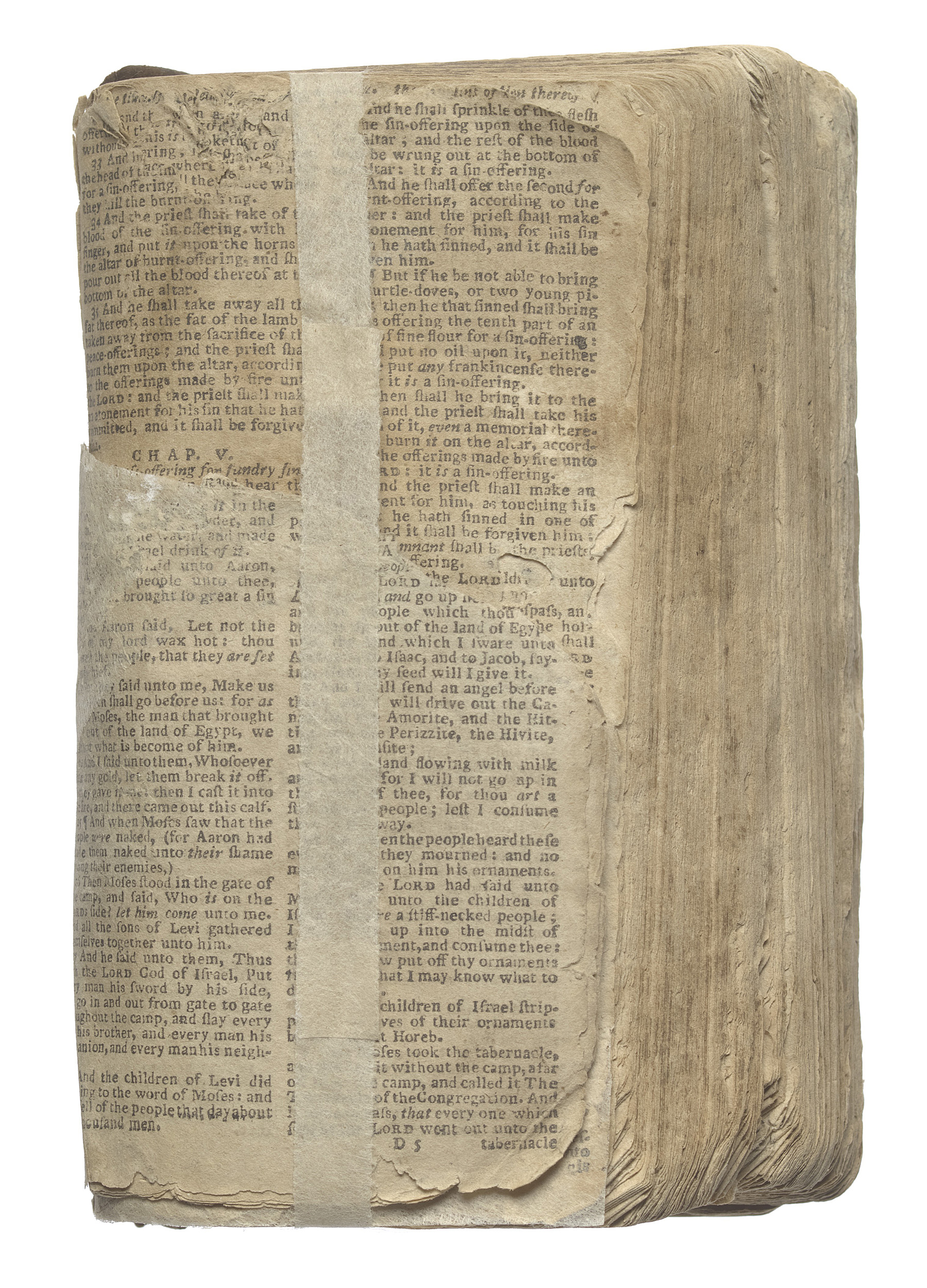

The role of Black Christianity in motivating our country’s largest slave rebellion, Nat Turner’s rebellion, Southampton County, Va., is only the most dramatic example of the text of the King James Bible being called upon to justify the violent revolutionary overthrow of the slave regime. But we need only look at the brilliant use of the church in all of its forms — from W. E. B. Du Bois’s triptych of “the Preacher, the Music, and the Frenzy” to the use of the building itself — to see the revolutionary potential and practice of Black Christianity in forging social change. What most intrigues me about Marx’s full quote is his realization that it is at once “the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering,” a crucial part of the quote that seems to have fallen away.

A Bible belonging to Nat Turner from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Nat Turner and His Confederates in Conference,” an engraving by John Rogers based on an illustration by Felix Darley.

Source: Gift of Maurice A. Person and Noah and Brooke Porter; “History of American Conspiracies,” 1863

People, of course, pray and worship for all sorts of reasons. Despite what Marx and the Black Panthers thought, the importance of the role of the Black Church at its best cannot be gainsaid in the history of the African American people. Nor can it be underestimated. It isn’t religion that keeps human beings enslaved; it is violence. Most normal human beings don’t need an elaborate religious belief system to resist the temptation to sacrifice their lives in the face of overwhelming odds and the certainty that they will be brutally suppressed and killed. That would be unreasonable.

The “failure” of African Americans to overthrow their masters, as the enslaved men and women did on the island that became the Republic of Haiti, can’t be traced to the role of the church per se, as Nat Turner’s decision to act based on his interpretation of prophecy attests. Early on, the church and Christianity played a role both in Black rebellions and in the preparation of Black people for leadership roles. Following Denmark Vesey’s alleged slave insurrection, Emanuel Church in Charleston, S.C., was burned to the ground; at the end of the Civil War, the Rev. Richard Harvey Cain left his congregation in New York to go south, to resurrect Mother Emanuel, and then, during Reconstruction, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. (Other churches would be the subject of deadly attacks and explosions carried out at the hands of white supremacists, most notably the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963, in which four little girls were killed, another was blinded, and more than a dozen people were injured.)

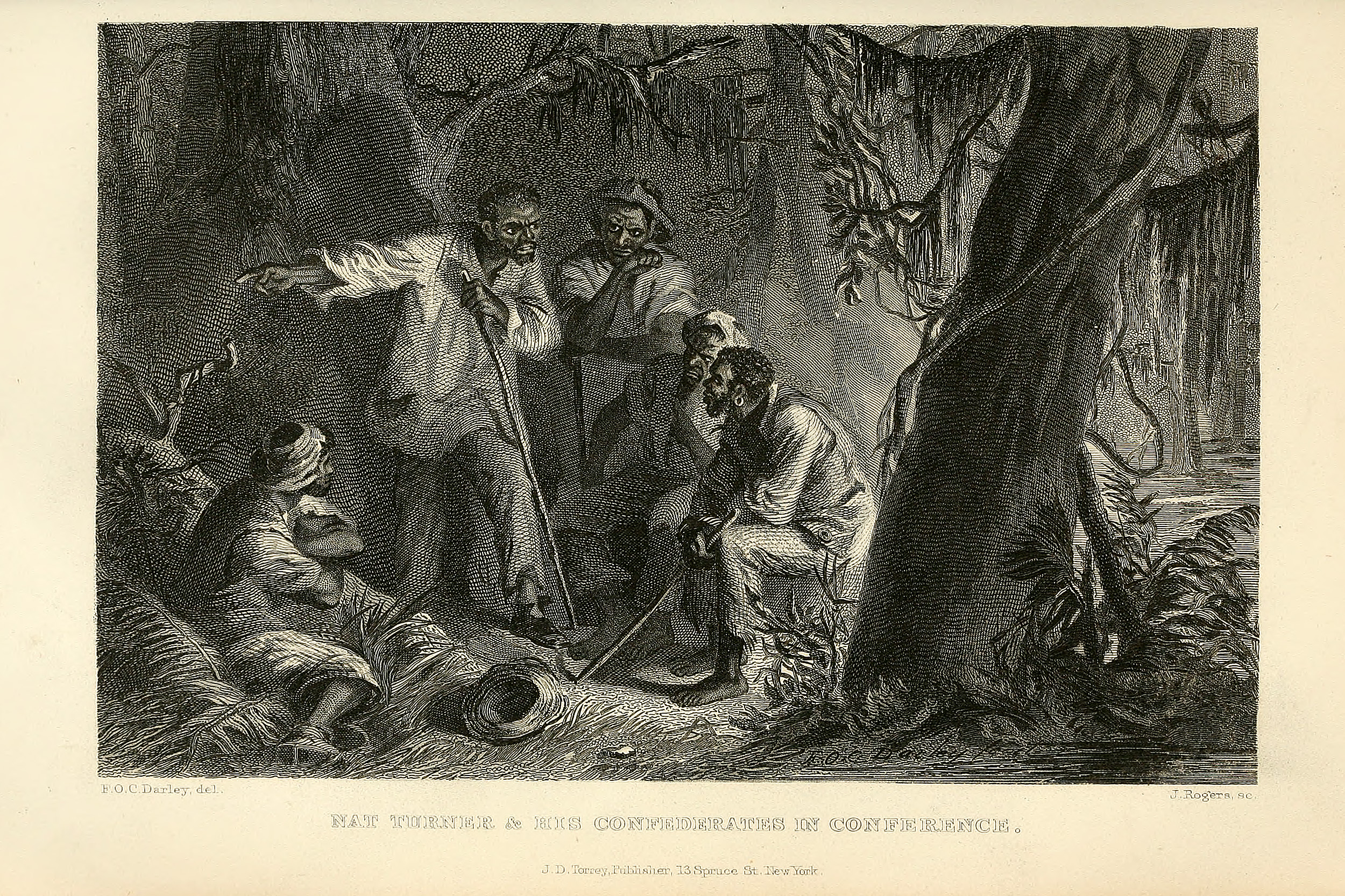

Martin Luther King Jr. speaking at an interfaith civil rights rally in San Francisco’s Cow Palace on June 30, 1964.

Photo by George Conklin/Creative Commons

Turner knew his Bible. Frederick Douglass, too, was thoroughly grounded in the church, having attended the Methodist church on Sharp Street in Baltimore while enslaved and then delivering his first public speeches — sermons — at the AME Zion Church (“Little Zion”) on Second Street in the whaling city of New Bedford, Mass. It has long been assumed that Douglass miraculously “found his voice” at an abolition meeting on Nantucket Island in 1841, three years after he escaped from slavery in Maryland, spontaneously rising to his feet in front of a roomful of white strangers. Not so, and he was even “ordained” in a way at Little Zion when he was about 21 or 22 years old. Like his father, the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., pastored at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church; unlike his father, he ran for political office and served in the U.S. House of Representatives. Powell effectively led the civil rights movement in the North until Montgomery, Ala., emerged as the epicenter of the movement and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became its most recognizable face and voice. I could provide many other examples. The Black Church has a long and noble history in relation to Black political action, dating back at least to the late 18th century. The failure of enslaved African Americans to overthrow the institution of slavery, as their Haitian sisters and brothers would do, cannot be traced to the supposed passivity inbred by Christianity; rather, it can be traced to the simple fact that, unlike the Black people enslaved on Saint-Domingue, African Americans were vastly outnumbered and outgunned. Violent insurrection would have been a form of racial suicide.

What the church did do, in the meantime, as Black people collectively awaited freedom, was to provide a liminal space brimming with subversive features. To paraphrase one of the standard phrases from the Christian tradition, one should never underestimate the power of prayer. Just ask Bull Connor or George Wallace. Without the role of the Black Church, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, with King by his side at both, and future congressman John Lewis, himself an ordained Baptist minister, present in 1965 — would never have been enacted when they were. There is no question that the Black Church is a parent of the civil rights movement, and today’s Black Lives Matter movement is one of its heirs.

U.S. Rep. John Lewis at Harvard’s 2018 Commencement, where he was principal speaker.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This is a truth made manifest in the mourning of Rep. Lewis this summer. In a season of pain marked by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and the murder of George Floyd, Lewis’s funeral included a service at Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma and his final crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. For Lewis, voting was sacramental, and he shed his blood for us to exercise this most fundamental of rights. In revisiting these sites and reflecting on his many marches for justice, “we, the people” once again bore witness to the deeper historical reality that faith has long been the source of the courage of those toiling on the front lines of change. As Lewis once put it, “The civil rights movement was based on faith. Many of us who were participants in this movement saw our involvement as an extension of our faith.”

One of the greatest achievements in the long history of civilization, as far as I am concerned, is the extraordinary resilience of the African American community under slavery, through the sheer will and determination of these men and women to live to see another day, to thrive. The number of Africans dragged to North America between 1526 and 1808, when the slave trade ended, totaled approximately 388,000 shipped directly from continent to continent, plus another 52,430 through the intra-American trade. That initial population had grown to some 4.4 million free and enslaved people by 1860. How was this possible? What sustained our ancestors under the nightmare of enslavement to build families and survive their being ripped apart and sold off in the domestic trade; to carry on despite not being able to ward off the rapacious sexual advances of their masters (a verity exposed by DNA, which shows that the average African American is more than 24 percent European); to acquire skills; to create a variety of complex cultural forms; to withstand torture, debasement, and the suffocating denial of their right to learn to read and write; and to defer the gratification of freedom from bondage — all without ever giving up the hope of liberty, as one enslaved poet, George Moses Horton, put it, if not for themselves, then for their children or grandchildren, when slavery had no end in sight? What empowered them with “hope against hope”? The writer Darryl Pinckney in a recent essay notes that “if a person cannot imagine a future, then we would say that that person is depressed.” To paraphrase Pinckney’s next line, if a people cannot imagine a future, then its culture will die.

“The importance of the role of the Black Church at its best cannot be gainsaid in the history of the African American people. Nor can it be underestimated.”

And Black culture didn’t die. The signal aspects of African American culture were planted, watered, given light, and nurtured in the Black Church, out of the reach and away from the watchful eyes of those who would choke the life out of it. We have to give the church its due as a source of our ancestors’ unfathomable resiliency and perhaps the first formalized site for the collective fashioning and development of so many African American aesthetic forms. Although Black people made spaces for secular expression, only the church afforded room for all of it to be practiced at the same time. And only in the church could all of the arts emerge, be on display, practiced and perfected, and expressed at one time and in one place, including music, dance, and song; rhetoric and oratory; poetry and prose; textual exegesis and interpretation; memorization, reading, and writing; the dramatic arts and scripting; call-and-response, signifying, and indirection; philosophizing and theorizing; and, of course, mastering all of “the flowers of speech.” We do the church a great disservice if we fail to recognize that it was the first formalized site within African American culture perhaps not exclusively for the fashioning of the Black aesthetic, but certainly for its performance, service to service, week by week, Sunday to Sunday.

The Black Church was the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designed to crush their spirit. Collectively and with enormous effort, they refused to allow that to happen. And the culture they created was sublime, awesome, majestic, lofty, glorious, and at all points subversive of the larger culture of enslavement that sought to destroy their humanity. The miracle of African American survival can be traced directly to the miraculous ways that our ancestors reinvented the religion that their “masters” thought would keep them subservient, Rather, that religion enabled them and their descendants to learn, to grow, to develop, to interpret and reinvent the world in which they were trapped; it enabled them to bide their time — ultimately, time for them to fight for their freedom, and for us to continue the fight for ours. It also gave them the moral authority to turn the mirror of religion back on their masters and to indict the nation for its original sin of allowing their enslavement to build up that “city upon a hill.” In exposing that hypocrisy at the heart of their “Christian” country, they exhorted succeeding generations to close the yawning gap between America’s founding ideals and the reality they had been forced to endure. Who were these people? As the late Rev. Joseph Lowery put it, “I don’t know whether the faith produced them, or if they produced the faith. But they belonged to each other.”

Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Henry Louis Gates Jr.