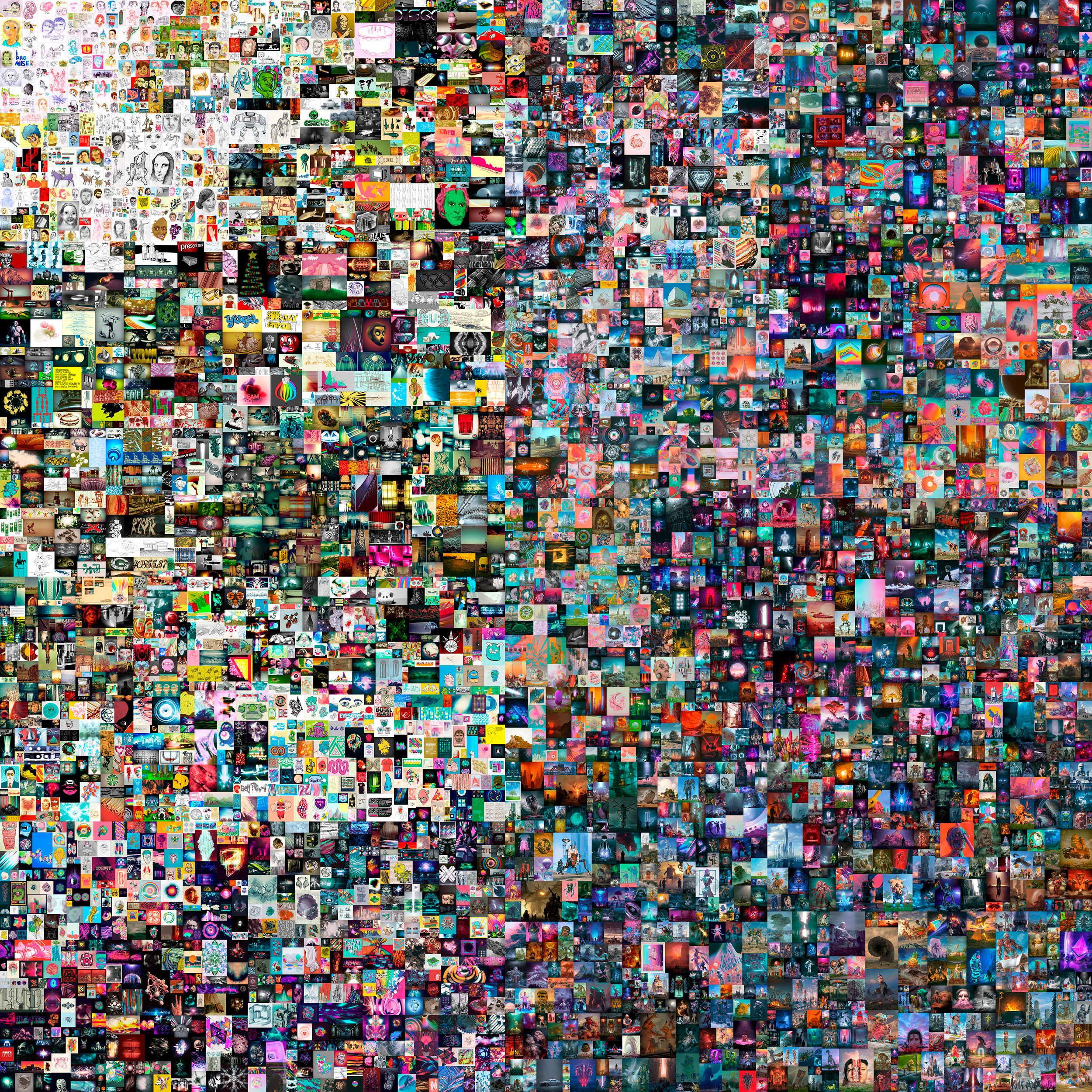

Detail of Beeple’s NFT artwork, “Everydays — The First 5000 Days,” which sold for $69 million at a Christie’s auction.

Credit: Christie’s Images Ltd. 2021

A digital piece of art worth $69 million

Harvard curator examines emerging new creative market

A digital collage of 5,000 images by the artist known as Beeple fetched an eye-popping $69 million at auction last week as a non-fungible token, or NFT, a type of digital file that uses computer networks to prove a digital item’s authenticity, paid for in cryptocurrency. It was a striking sum for something that can so easily be copied and co-opted by anyone with an internet connection, according to many experts, and the first for the revered auction house Christie’s, which orchestrated the sale, and opened the bidding at a modest $100. While the final price tag for Beeple’s “Everydays — The First 5000 Days,” didn’t come close to the $450.3 million paid for Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” (“Savior of the World”), a portrait of Christ dating to about 1500 that sold at Christie’s in 2017, it was a stunning price for something that to many seems intangible. It ignited a discussion about the nature of art in the digital age, and how to measure its worth. The Gazette spoke to Mary Schneider Enriquez, Houghton Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, about the sale.

Q&A

Mary Schneider Enriquez

GAZETTE: As an art curator, what is your impression of the Beeple piece?

ENRIQUEZ: One of the first things I considered was the use of pop culture imagery in the Beeple piece, and how I’d compare that to the work of Andy Warhol. Looking back on the ways Warhol used popular culture, there’s a very distinct line in my mind between why Warhol’s work is interesting and how he really challenged us to think and see differently, versus the way Beeple’s work and use of popular imagery challenges me. This is a whole different way of creating, and my initial reaction when I first heard about the sale was, “Wow, there’s an excessive amount of money in the market.” It seems to me that this is about money, and it’s about ownership, more than it is about a form of art in the spheres in which I, as a curator, have been trained to think about a work of art and its care. The idea that there is one, authentic copy attached to a digital certificate of ownership does help me put it in a context of art history, and the idea of the original and the copy. But at the same time I would ask, what is an authentic copy, what does that mean in this case? Everything, it seems, can be adulterated online, literally everything. And there are so many variables to this “work of art” that ultimately link to its value as a kind of commodity, as a collectable linked to cryptocurrency. In short, it seems to me that this is a work for speculation in the cryptocurrency world. This raises numerous red flags when I consider the idea of this as an art object based on my work in the museums.

“One of the first things I considered was the use of pop culture imagery in the Beeple piece, and how I’d compare that to the work of Andy Warhol,” said Mary Schneider Enriquez, Houghton Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

GAZETTE: With other forms of art like sculpture or paintings, value is often connected to rarity, quality, condition, and provenance. But with this type of piece it’s hard to apply those types of standards, so how exactly is it assigned value?

ENRIQUEZ: I think the value question is related directly to this world of cryptocurrency. Christie’s, from what I understand, didn’t have a structure for what a minimum bid should be, so it started at $100 and the bids rose to insane levels because there was an incredible energy and demand for this collectable from a certain world of collectors. The buyer, from what I can tell, is a crypto investor. So it seems to me that the value is utterly speculative and is tied to the notion of flipping, which is one of the things I have often worried about with young artists when their work becomes popular. People buy it at a price, flip it at auction, and sell it for a higher price, or use it as an example of an investment triumph generating demand from other investors, even though the artist does not end up earning much from this. Hence the artist’s work is used solely as an asset, a currency.

Similarly, in the case of NFT’s, although the artist is supposedly guaranteed a percentage, there’s a speculative sense about Beeple’s work, which is driving the price to exaggerated heights in cryptocurrency. I’m not an economist so I cannot fully explain the world of cryptocurrency, but I must ask, how can one be certain of the value of $69 million in cryptocurrency? How do we measure that amount of money in dollars versus cryptocurrency? Is the cryptocurrency value absolute, or is it relative, and as such, is the Beeple’s piece worth $69 million in U.S. currency? By selling this work at a Christie’s contemporary art auction, a level of value is given, framing the Beeple’s piece as a work of art, a new one, at that. And finally, by bidding up the price, value is added to cryptocurrency itself, as well as to the collectible, Beeple’s piece.

I have another question in this regard, because of its format, and that it can be shown everywhere online in little bits, and anyone could build this work, how do we measure the originality? Is it based on the fact that Beeple did this first? And does originality matter in this case? I understand that the collector plans to create an online museum for the piece and that it will be accessible to anyone through their internet browser. It will be available to all and that is exciting. How do I define whether it is art or not? I don’t know that I can answer that right now, I’m still thinking this through. And I certainly cannot value it by the standards determined by the crypto market.

GAZETTE: Can you draw any comparisons between the price paid for this work and the $120,000 that was paid for a banana duct-taped to a wall in 2019?

“One of my big concerns would be how we can be certain that we will have the technology in the future necessary to show this type of piece. That is a fundamental issue …”

ENRIQUEZ: That’s a good question, and while I think the banana was crazy, I also think it links back, in my mind, to [Marcel] Duchamp and to some of the questions about what is art. In looking at contemporary art, one often views the work not only for what one sees, but for the idea it presents and questions it raises, placing it within the context of art history. The intentions and the creative process of Beeple’s work raise questions in my mind. I don’t know that I can measure it.

I’m going to be frank — I came into this conversation feeling less positive about this as an art form based on my experience working with art objects. I think because it is an NFT and it seems to exist and be constructed more as a collectable for a cryptocurrency culture than as a work challenging or grappling with the origins definition or meaning of art, it leaves me with many questions and few answers at this moment.

I have said repeatedly, referring to the moment we’re living in, that if we look back in time over history at various civilizations and various cultures, trauma, war, and extreme hardship have always been present. And the arts in some form, whether in the written, theatrical, musical, or visual form, have always spoken to the human spirit and provided an essential source of hope and strength. I have a difficult time thinking of this Beeple work as something that expresses the human spirit and gives me that sustenance, nor do I think it represents what I refer to in history. But that is very much my view.

GAZETTE: Would the museum ever consider acquiring this kind of digital work?

ENRIQUEZ: I think we could consider it, but, as with all our new acquisitions, it would be important that we fit a new work of art from whatever time period into the context of our collection. It would need to build upon our historical up to our 20th- to 21st-century collections, creating dialogues with the objects that would allow us to challenge and learn from the history of art in our teaching museums. That factor of teaching with objects, of the importance of grounding each work of art in the past as well as the present and in what artists are creating, the risks they take and paths they forge, is an essential aspect of who we are. I think that is the critical perspective necessary in weighing the importance of a particular digital work for our collection.

GAZETTE: Do you have concerns about acquiring and preserving this kind of digital artwork?

ENRIQUEZ: One of my big concerns would be how we can be certain that we will have the technology in the future necessary to show this type of piece. That is a fundamental issue — if we don’t have the technology, there will be no digital artwork to show in our museums. This question of preservation is something I think a lot about with regard to a number of more contemporary works in the Harvard Art Museums. For the Nam June Paik work, for example, we’ve had to scour eBay to collect older television sets, so that we have what is necessary to install his work properly if the original pieces fail. There is also the Jenny Holzer horizontal electronic LED sign currently installed on the ground floor. When something connected to that piece breaks, it has to be fixed, and the question becomes, do we try to source the original technology, or is there a newer version that the artist has approved? As curator in a museum in which you acquire objects that you hope and expect will exist for hundreds of years, there are a number of issues raised by the technology necessary for a work like Beeple’s. Those kinds of issues are extremely important in a museum context, and I worry with this particular work that these issues would pose an enormous challenge for future generations.

Interview has been lightly edited.