7 million face shields and counting

How a Wyss Institute COVID-19 project led to regional, scalable PPE production

The lightweight die-cut Dome Shield, one of the designs created by the Wyss Institute and Lacerta, has a unique full-coverage geometry and can be mass-produced at low cost.

Images courtesy of James Weaver

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe in early 2020, a new three-letter acronym spread with it: PPE, short for personal protective equipment, which was suddenly both in high demand and short supply. Lockdowns to curb the virus’ infection rate disrupted the worldwide supply chains that moved products between designers, manufacturers, assemblers, distributors, and customers, revealing that the global consumer economy was like a house of cards — structurally impressive, but fragile.

Local labs, maker spaces, and hobbyists with access to 3D printers jumped into the fray, helping to fill the gap between PPE supply and demand by manufacturing face shields and other equipment for frontline health care workers. Multiple groups at the Wyss Institute used 3D printers and laser cutters to prototype and produce face shields that were evaluated at several Boston-area hospitals, and nearly 1,000 of them were then distributed to local hospitals and clinics.

But a co-leader of that effort, James Weaver, knew they could do more.

“It was wonderful to see everyone coming together to make and deliver face shields so quickly, but as the pandemic continued to grow, it was clear that we weren’t going to be able to produce them in the lab at the volumes needed to sufficiently protect our health care workers,” said Weaver, who was a senior research scientist at the Wyss Institute at the time and is now a senior staff scientist at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

So, Weaver started talking to clinicians at local hospitals, asking what features they needed in a face shield that might offer improvements over more traditional designs. Due to ongoing supply chain problems and facing domestic foam and elastic shortages, he asked potential users whether it would be acceptable for the face shields to be made out of a single material that was easy to manufacture, rather than the separate plastic, foam, and elastic components that go into traditional designs. “The front-line medical workers we collaborated with were very enthusiastic about participating in the face shield design process, and the prototypes we came up with together offered new features that weren’t available in existing products. Learning how open they were to alternative materials and form factors completely changed how we approached this manufacturing effort, which was very exciting for all of us,” said Weaver.

Local connections, national impact

The collaborative team co-led by Weaver and Wyss core faculty member Jennifer Lewis, ultimately grew to include researchers from Columbia University and Lacerta Group, Inc., a Mansfield, Mass.-based plastic food packaging manufacturer.

“Early on, when COVID-19 first hit, Lacerta received requests through friends and family for face shields. Working with James and the team from the Wyss Institute, within days we were able to design and produce face shields, and we ramped up production capacity within a couple weeks to meet the needs of the medical community,” said Craig Muldrew, vice president of sales and marketing at Lacerta.

Lacerta provided materials to Weaver’s team for testing and design optimization based on feedback from clinical users, and by early April they had started manufacturing them at an industrial scale. Today, they’re being produced at a pace of up to 400,000 per day, and over 7 million face shields have been shipped both locally and nationally for use in the health care, food service, manufacturing, and academic research communities. This effort has been a labor of love for Weaver, who has personally driven thousands of miles across New England over the past few months to meet with clinical collaborators and deliver boxes of face shields to customers.

To meet the diverse needs of different users, the collaborative team came up with a series of anti-fogging face shield designs ranging from the more traditional “Lacerta Shield” to the full-coverage “Dome Shield” that provides additional protection, all of which are made of food-grade materials in Lacerta’s FDA-approved manufacturing facility in Massachusetts. The face shields range from 40 to 75 cents each (about 1/5th the price of their closest mass-produced alternatives), and are available from www.Lacerta.com or www.Dome-Shield.com. The team has also donated face shields to support several local, regional, and national humanitarian efforts, and the designs have been very well received by the local communities.

“A well-designed, affordable face shield, like the Dome Shield, protects the wearer’s face and contain coughs, greatly reducing community transmission if widely used,” said Eli Perencevich, a professor at the University of Iowa who was an early promoter of the Dome Shield. “Since March, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics have distributed face shields to all employees in order to create a safe healthcare environment, and we have been encouraging face shield use in the community to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and help with containment.”

Because the Dome Shield is made of only one material, which Lacerta makes in-house, its production does not compete for the same strained supply chains on which most other manufacturers rely. As a result, the face shields can be manufactured at a much greater scale than university-led PPE production efforts. Lacerta also internally recycles its leftover and excess material into new products for an efficient, zero-waste manufacturing process.

“As the country’s economy reopens and people start to go back to work, many of the companies and organizations that temporarily switched to manufacturing PPE are going back to producing whatever it is they usually sell. We are confident Lacerta can take on increased demand for our face shields as a result of that shift,” said Muldrew.

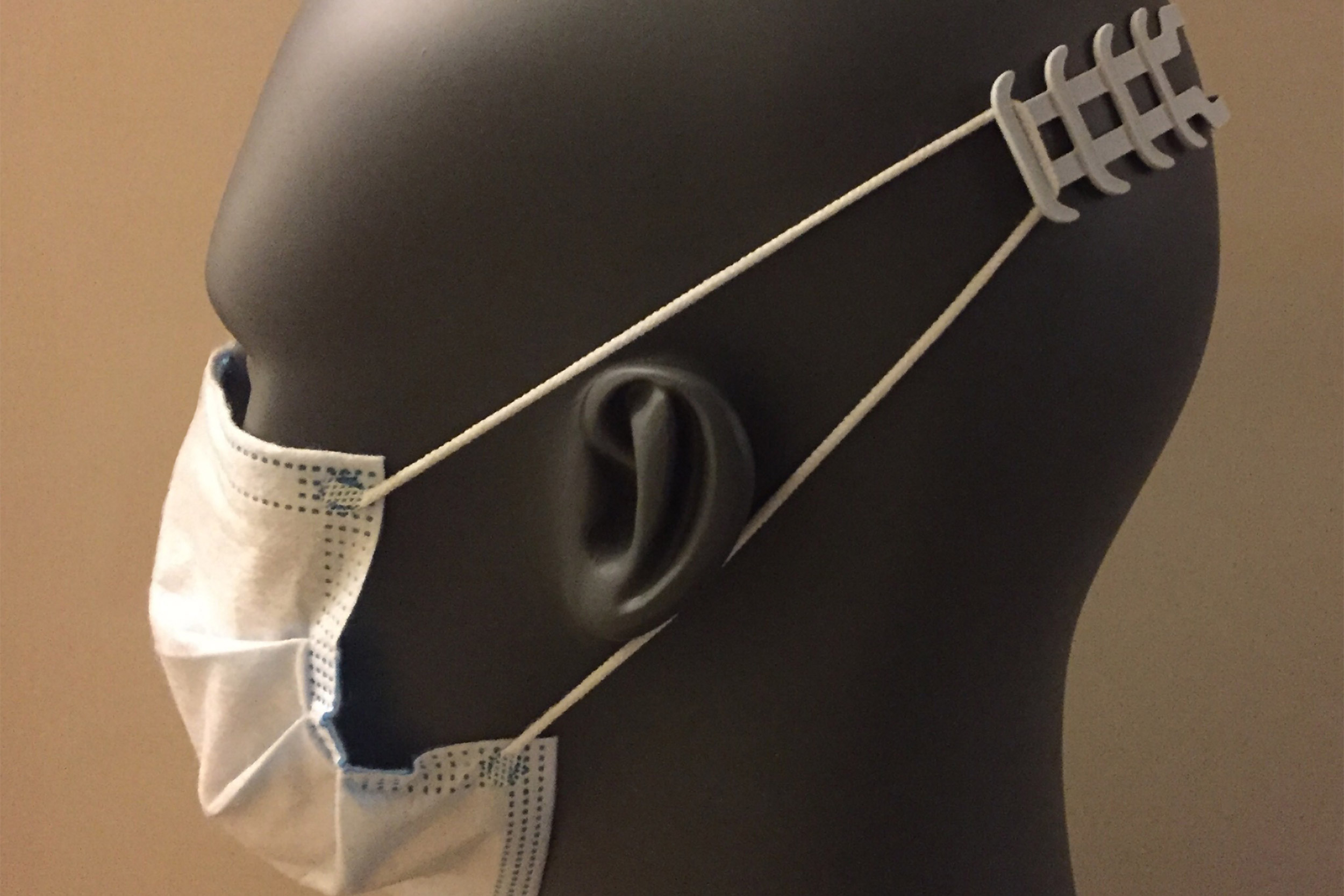

Ear savers for life savers

Lacerta isn’t the only manufacturer with whom Weaver has connected about PPE manufacturing needs. He is also working with Cromwell, CT-based ACT Group to mass-produce an ergonomic accessory for surgical masks called “ear savers” that relieves the ear discomfort caused by wearing a face mask with elastic ear loops for hours on end. “Medical professionals typically don’t wear their masks for 12 hours a day, multiple days in a row, and now there are millions of people doing exactly that to stay safe. Those masks simply weren’t designed for long-term comfort,” said Weaver.

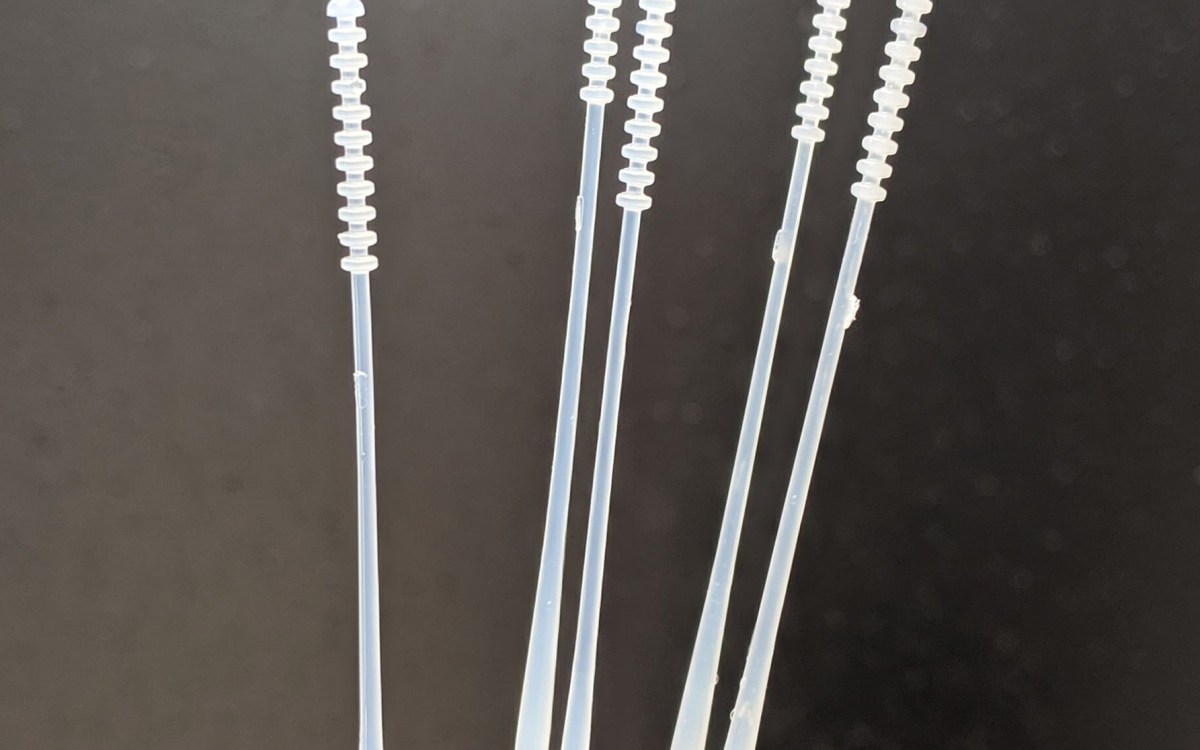

The collaboration has leveraged ACT Group’s state-of-the-art additive manufacturing expertise and built on existing designs developed within the global maker community. The high-throughput 3D printing techniques employed as part of this collaboration were critical for producing the quantities needed within the required timelines.

“ACT Group has been involved in developing and producing various PPE designs for the scientific and medical communities to address COVID-19,” said Emily Turcan of ACT Group. “When James Weaver reached out, there was no question we were going to help, and our durable, yet flexible nylon material turned out to be a perfect match for the ear savers project.”

To date, over 30,000 of these accessories have been distributed to doctors in the Boston area, and more are being printed daily. ACT Group stands ready to increase production or aid in the tool-up required to switch from additive manufacturing to injection molding, depending on demand.

More like this

“All of the designers, researchers, physicians, hospitals, and industrial partners that have been involved in these projects have been amazing,” said Weaver. “They committed time, effort, and resources into helping develop these face shields and ear savers, saying ‘yes’ when they could have easily said ‘no.’ And now millions of people can protect themselves while working essential jobs to get our country through the pandemic. I’m humbled to be part of that team.”

One of the collaborators who said “yes” early on was Tod Woolf, the executive director of the Technology Ventures Office at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “The pandemic presented lots of complicated problems that needed an engineer’s mind and dedication to solve, and James was right there on the front lines whipping off prototypes, driving samples to clinicians, and coordinating with suppliers. At Beth Israel, we’re now trying to brace ourselves for a second wave of COVID-19 as cold weather arrives and the risk of transmission increases, and fortunately, the Lacerta shields are on the list of products we know we can buy when we need them,” Woolf said.

Other members of the Wyss and Harvard face shield and ear saver R&D teams include staff engineer Tom Blough, 3D printing specialist Ted Sirota, research associate Sébastien Uzel, postdoctoral fellows Sanlin Robinson, and Daniel Reynolds, and Harvard Graduate School of Design student Lara Tomholt.

“This effort exemplifies the proactive, collaborative, can-do attitude that defines the Wyss Institute and the culture we have created,” said Wyss Institute’s Founding Director Don Ingber. “When confronted with the problem of critical PPE shortages due to the pandemic, James and his teammates selflessly stepped up and created a solution that is helping to keep millions of people safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. We couldn’t be prouder of them for their creativity, drive, and perseverance in confronting this ongoing crisis.” Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.