Suffrage parade in Boston, 1914.

Photo courtesy of the Women’s Rights Collection, Schlesinger Library

The long march for suffrage

Radcliffe project marks 19th Amendment centennial while focusing on the women who would not be fully enfranchised for decades more

The ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting women suffrage, was clearly a milestone in U.S. legal history. Many historians, however, would argue that transformative social change is the result of a continuous struggle rather than a single event.

Enter the Radcliffe Institute’s “Long 19th Amendment Project,” which is playing a leading role nationally in reframing our understanding of the history of the suffrage centennial and its meaning, with support from the Mellon Foundation. This is fitting, because it was alumna and suffragist Maud Wood Park’s donation of her papers that formed the core of what would one day become Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library.

The project invites us to look beyond the accepted histories of the suffrage movement — beginning with the Seneca Falls convention in 1848, which is seen as the genesis of the movement even though women’s activism had actually begun much earlier.

It also looks beyond celebrations of the elite white “Founding Mothers” Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and toward the African American, Latina, and Indigenous women who would not be fully franchised for decades to come. At the heart of these efforts is the Long 19th Amendment Project Portal, an open-access digital gateway to archival collections, teaching materials, and scholarship that help to tell a more complex and inclusive story about gender and voting rights in America.

In two interviews, Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who is also the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School and a professor of history, and Jane Kamensky, Pforzheimer Foundation Director at the Schlesinger and Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History, shed light on some of the historical issues framing the project.

Q&A

Tomiko Brown-Nagin and Jane Kamensky

HLS: Let’s start with the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. The standard narrative places that as the start of the women’s suffrage movement, yet some historians would argue that it was more a movement for social and property rights, and that suffrage was not high on the agenda.

Kamensky: The cutting edge of work around suffrage is that Seneca Falls is a false beginning. It’s a landmark that we look to, which places Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a subset of the women’s rights movement [at the fore], with suffrage as their main and exclusive goal. And that leaves out the activism that happens decades earlier in African American communities, in churches, and even women who were voting. We’re learning a lot more about women in New Jersey and New England states who were voting under the exceptions that state constitutions allowed before 1807. So part of the commitment of Schlesinger Library’s Long 19th Amendment Project is that the story is more complicated and begins earlier.

Engraving of Ida B. Wells, published in The Afro-American Press, 1891; graphite and ink drawing of Fannie Barrier Williams, ca. 1900, unknown artist.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress; Mary Earhart Dillon Collection, Schlesinger Library Prints and Photographs Division

There is an important book about this by Lisa Tetrault, “The Myth of Seneca Falls,” which you have probably seen. Of course the Seneca Falls convention is also famous for having Frederick Douglass among its luminaries, and I think reminds us that abolitionist activity and women’s suffrage activity were very tightly braided together until the post-Civil War period, when some suffragists made choices between what they were asking for women and what the Constitution had granted to African American men.

HLS: Did Seneca Falls do anything to actually change history?

Kamensky: What comes out of Seneca Falls, and the reason we treat it as an origin point, is the published Declaration of Sentiments that mirrors Jefferson and his committee’s draft for the Declaration of Independence, and that claims for women the banner of “all men are created equal,” in that famous formulation. But for that declaration being published in newspapers — including abolitionist newspapers — and circulated, I don’t think we would be teaching Seneca Falls as the beginning of the suffrage movement. It’s a small convention in a series of other conventions around rights claims in the 19th century.

HLS: At the time the 19th Amendment was passed, many women were already enfranchised, while others still lacked voting rights. So how significant a landmark was 1920?

Brown-Nagin: The 19th Amendment did increase the electorate, but it fell far short of what we would think of as universal voting rights. The broader timeline helps us to contextualize older narratives, including the history of elite white women like Susan B. Anthony and Alice Paul. Those stories are important, but they are complicated by racism and nativism. So, 1920 is an important moment, but celebrating the centennial without understanding the greater historical context eliminates many of the fascinating facets of the struggle for women’s suffrage.

To commemorate the amendment’s ratification on “Equality Day,” Aug. 26, 1920 — as well as the Schlesinger Library’s founding on the same day in 1943 — Radcliffe is launching a virtual lecture series, “Voting Matters: Gender, Citizenship and the Long 19th Amendment,” with a talk by legal historian Martha S. Jones of Johns Hopkins University. Jones anchors the generations-long movement for women’s suffrage in the activism of African American women struggling for political power in the 1830s.

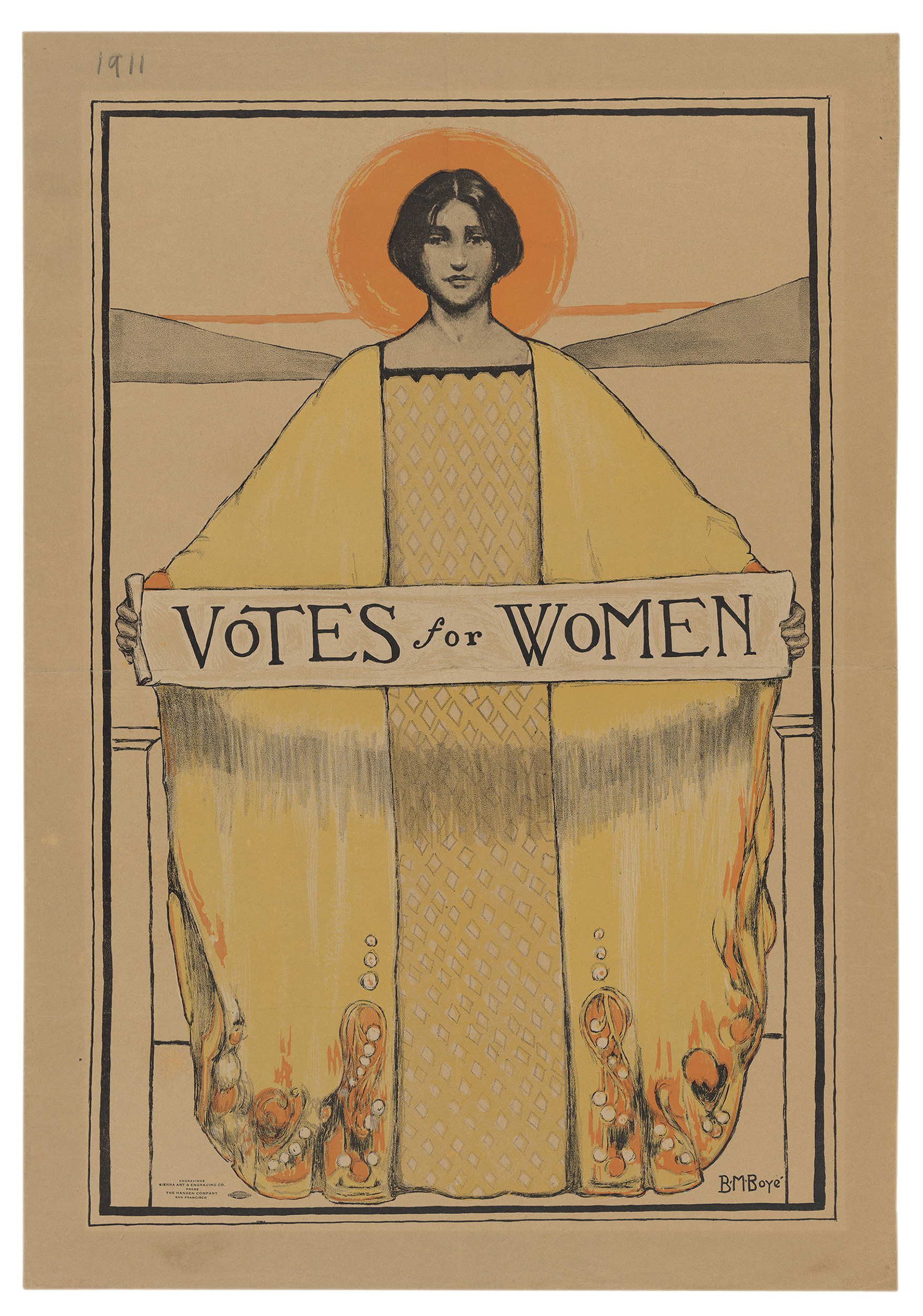

A suffrage postcard featured as part of the project; and a portrait of Mary Church Terrell the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, launched in 1896 to fight for the vote and for civil rights.

Courtesy of Barbara F. Lee of Cambridge, Mass.; courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Kamensky: I think it’s important to say here that there is no right to vote in the United States Constitution or its amendments. There are only a series of removals of barriers on account of sex, in the formulation of the 19th Amendment, or on account of former servitude in the Reconstruction amendments. The 19th Amendment does nothing to disturb the state based racial order in the South, it doesn’t enfranchise women in the U.S. territories, and the Indigenous women who acknowledge multiple sovereignties are not making suffrage claims under the 19th Amendment.

The 19th Amendment is the first time women enter the U.S. Constitution, so we felt that its centennial was an appropriate moment of commemoration and reckoning. But not because it was the silver bullet of sex equality, nor was it meant to be.

One of the reasons that the 19th Amendment was finally passed was precisely because it left other barriers in place. And some suffragists in the years immediately preceding its passage were making the argument that women — generally coded to mean white women — will bring a civilizing influence to the American electorate. In our virtual exhibit “Seeing Citizens,” there are examples of visual propaganda, and one of the things suffragists were saying that seemed most persuasive to their audience was that various categories of people who would rank in their order of civilization below white women are already voting: Convicts are voting, “idiots” are voting, to use their category of mental defectives, and women are not. So to a certain degree, it’s by promising to leave other barriers in place that suffragists succeed.

One of an estimated 100,000 tin signs that were posted on “Suffrage Blue Bird Day,” July 9, 1915, by supporters and members of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association; a suffrage poster from 1913.

Grace Johnson Papers in the Woman’s Rights Collection, Schlesinger Library; Poster Collection, Schlesinger Library

HLS: At the moment there are many pending issues of voter disenfranchisement which may play out in the next election. What kind of scenarios are you anticipating, and do you think that certain groups, including women and people of color, will be most affected?

Brown-Nagin: The battle for full citizenship and to achieve equal voting rights is still very much alive. There are struggles over mail-in ballots, there are efforts to suppress votes, and the infrastructure of voting is inadequate in many communities. The struggle over the rights of felons to vote also is important; the growth of the U.S. prison population in the last four decades has left more than 6 million voters banned from the polls today. Policies vary from state to state, but disenfranchisement affects communities of color disproportionately. Nationwide, it has estimated that one in every 13 black adults was prohibited from voting in the last presidential election as the result of a felony conviction. And in four states — Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia — more than one in five black adults were disenfranchised.

At the same time, we are also seeing public discussion of how important racial minorities are to democracy, and to electoral outcomes. There are examples in the ways black women contributed to the election of Doug Jones to the Senate in the 2017 special election in Alabama, or to Stacey Abrams nearly winning the 2018 gubernatorial race in Georgia. So one can understand why there continues to be resistance to greater enfranchisement in certain sectors, because when women and people of color do vote, it’s a powerful portion of the electorate.

I think the bottom line is that the struggle over who votes and under what terms is just that — a struggle. As historians, both Jane Kamensky and I are naturally interested in the history of the 19th Amendment. One of the things we see in that history, which remains very much part of our present, is that shifts in political power are always contested. The coming years will be no exception. But it is our responsibility to ensure that all Americans can exercise the rights of citizenship; the well-being of our country depends on it.