This fall, Professor Tiya Miles will teach “Abolitionist Women and Their World,” a course in public history.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Crowd-sourcing the story of a people

Tiya Miles details how public history can reshape our views of the past

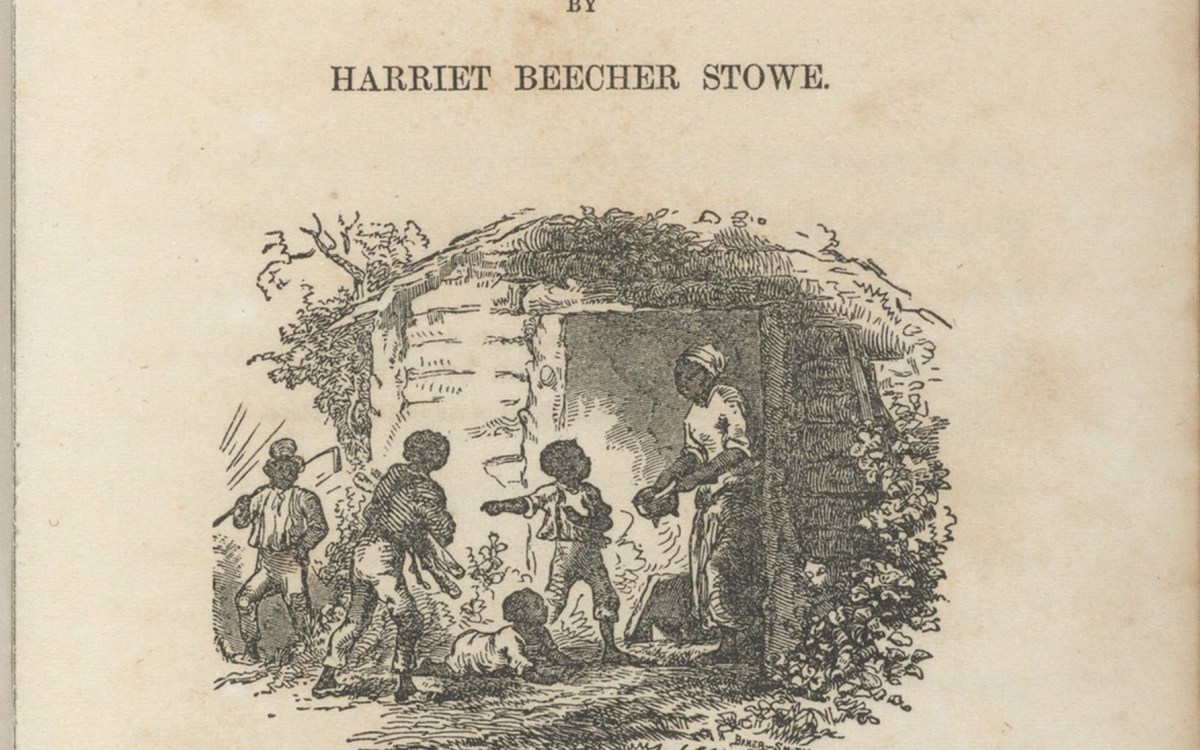

Tiya Miles believes a better understanding of the past is as likely to be found in a formal archive, a National Park, or a conversation with an elderly relative as it is in the classroom. Miles, who received a bachelor’s degree in Afro-American Studies from the College in 1992, joined the faculty in 2018 as professor of history and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She is also the new director of the Warren Center for Studies in American History. Her prize-winning research focuses on African American, Native American, and women’s history in the 19th century, with special attention toward issues of slavery, interracial family and community relations, environmental justice, and links between Black and Native experiences. Next spring, she will teach “Abolitionist Women and Their Worlds,” a public history course supported by the Schlesinger Library Long 19th Amendment Project and the Mindich Program in Engaged Scholarship. She spoke to the Gazette about the vital role of public history in shaping American cultural understanding.

Q&A

Tiya Miles

GAZETTE: What first drew you to public history?

MILES: When I began my journey in the landscape of public history, I didn’t even know I had taken the first steps. As a middle schooler, I had two favorite pastimes. Unbeknownst to my parents, I would let myself into the abandoned 19th-century houses in my downtown neighborhood in Cincinnati, examine the rubble around me, and imagine who had lived in these structures. I also grew up listening to my grandmother’s stories on her front porch as I helped her snap the green beans or clean the collards that she grew in her side yard. When I heard her describe the family farm back in Mississippi that was lost when a group of white men tricked my great-grandfather — who could not read — into placing his X-mark on a document, and her move north with several children in tow in the 1940s, and the challenges of urban life, I felt the urge to write it all down. I still have the scribbled notes. I was conducting a rudimentary form of oral history, a key method of public history, back then.

Public history has multiple definitions in part because it is a boisterous, crowd-sourced endeavor. The key trait of the field is an engagement with history beyond the walls of the campus or classroom. Because public history meets people where they are and affects how they make sense of their lives, it is a field complicated by public memory, emotional investments, and competing group aims. All of this makes the work thrilling and satisfying, but also vexing, time-intensive, and difficult.

GAZETTE: What might be surprising to people about public history and how we engage with it?

MILES: Museums, historic sites, archives and libraries, government offices, community organizations, local exhibits, and performances are all common sites of public history. If you frequent these places and find yourself reading plaques, listening to tour guide narratives, or examining images of historical figures, you are engaging with the work product of this field. Most people, though, engage with the past in intimate ways: when they listen to multigenerational family stories around the holiday dinner table, flip through a family photo album, view a historical mural on the wall of a church, or curl up with a work of well-researched historical fiction. These are encounters with the past that can enrich people’s everyday lives, contribute to the shape of personal and community meaning-making, and inspire commitment to civic engagement.

Sometimes critics expect public history to be less thoughtful than historical investigations carried out by academics at universities. This misguided view marginalizes, and indeed disrespects, a wide range of nonacademic knowledge producers and the communities they represent. Intellectuals and researchers outside of universities, including local knowledge holders, oral historians, family historians, historic-site tour guides, and National Park Service interpreters who may not have pursued advanced academic training, create and share knowledge that is essential to the building of multifaceted understandings of the past and to the dissemination of those understandings.

“Sites that mark histories of slavery need to be acknowledged in a way that embraces whole truths to the extent that we can arrive at them and tend with sensitivity to the present needs of people encountering this traumatic past.”

GAZETTE: You taught a new seminar, “Slavery and Public History,” this spring. What were some themes you focused on?

MILES: I was very pleased to offer this seminar for the first time as part of an effort encouraged by the former chair of the History Department, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, to highlight public scholarship and expand curricular options for our students. We discussed controversial cases of public interpretation of the history of slavery, such as the renovation of the Liberty Bell complex on land where enslaved people once labored in Philadelphia, and the portrayal of a slave auction at Colonial Williamsburg. We delved into the commercialization of plantation landscapes and histories in the form of tourism and wedding planning. We examined fiction, biography, and a range of digital databases and online representations of slavery. Most memorably for the students, we visited the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Mass., and participated in a moving tour with board Co-President Penny Outlaw. Royall family funds were instrumental to the founding of Harvard’s Law School, and imagery from the Royall family coat of arms formerly appeared on the School’s crest.

This class was absolutely invigorating and, incredibly, functioned well even after the COVID-19 disruption. It included a lively, multidisciplinary bunch of brilliant undergraduate and graduate students, as well as fellows from other universities. They researched a range of topics, from the lack of interpretation of Indigenous labor exploitation at a 17th-century Spanish mission and National Historic site in Los Angeles to the complicity of social media platforms in the circulation of racialized stereotypes, such as a TikTok meme in which users are encouraged to mimic the physical stance of a Black person picking cotton.

GAZETTE: The course ended prior to the start of this protest movement against anti-Black racism and police brutality and a renewed mainstream attention on how this current moment emerged. What have you heard from your students since the protests began?

MILES: They have been sharing feelings of shock and vulnerability as COVID-19 spreads and differentially impacts communities of color, as well as their feelings of increased politicization in response to recent acts of police violence. In our course, we discussed how histories of Black and Indigenous enslavement in what is now the U.S. spawned legacies of inequality that continue today. The students recognize in this moment a meta reflection of issues we discussed: histories of racial oppression, societal avoidance of ugly realities, and the sanitization of national narratives. They do not want to be alone with their troubling realizations. I have been informally encouraging conversations between pairs and groups of students who share questions and research topics in common. As we discussed throughout the semester, the way we work together as learners can also embrace the collaborative methods of public history.

More like this

GAZETTE: How do current conversations and actions around statues of racist historical figures affect the direction of public history in the U.S.?

MILES: We are currently seeing public history investments and contestations play out writ large in the debate about statues of Confederate generals and other historical figures whose actions have come under fierce criticism. As numerous historians have noted in public venues, these statues say more about the times when they were erected (such as the Jim Crow era) than about the times they purport to reflect (such as the Civil War era). Public history scholarship has again contributed to the conversation, often serving as the source for reexamination of famous figures like South Carolina Sen. John C. Calhoun and relatively lesser-known figures like Michigan Gov. Lewis Cass. My most recent book, “The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits,” was cited in news coverage about why the present governor of Michigan, Gretchen Whitmer, refused to name a new building after Cass and why members of the state legislature want his statue removed from the capitol.

While I have a personal view about problematic statues — no historical representation is sacrosanct; vaunted public symbols should reflect shared public values; statues should be thickly interpreted whether or not they are removed — I believe decisions about each statue should be deliberated at the local level by and with community members who live in the shadows of those landmarks.

GAZETTE: What needs to change in American public history education for people to really understand and grapple with the legacy of slavery?

MILES: Sites that mark histories of slavery need to be acknowledged in a way that embraces whole truths to the extent that we can arrive at them and tend with sensitivity to the present needs of people encountering this traumatic past. The last decade has ushered in significant change in the interpretation of house museums and agricultural sites, such as the incorporation of enslaved people’s presence in plantation tour narratives, the renovation and interpretation of slave quarters, and the opening of innovative educational sites such as the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana. These gains, while still limited in depth and scope and in need of further development, stem from audience mobilization and public history scholarship that revealed appalling gaps between historical reality and historical presentation and formulated recommendations for conveying fuller renderings of the past.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.