Demonstrators protest the death of George Floyd outside the U.S. Capitol in Washington.

Jacquelyn Martin/AP Photo

After the protest … what next?

Harvard experts talk about how to turn the moment’s energy into lasting change

The continuing nationwide demonstrations launched after the killing of George Floyd have sparked a debate among minority groups and leaders, activists, academics, and public officials over how best to convert the energy of this moment into meaningful and lasting change. Some have called for overhauling laws that shield police officers from accountability or allow practices that have tended to lead to excessive force disproportionately used against African Americans. Others want to shrink the ranks of officers and shift the funding to increase social services, thereby reducing the need for enforcers. But for many, racial violence is just one manifestation of wider systemic disparities facing African Americans in arenas such as health, education, employment, economy, and housing that also must be addressed. The Gazette asked faculty members across the University to share their views on this question: What actions would you most like to see taken next to begin building a more just society?

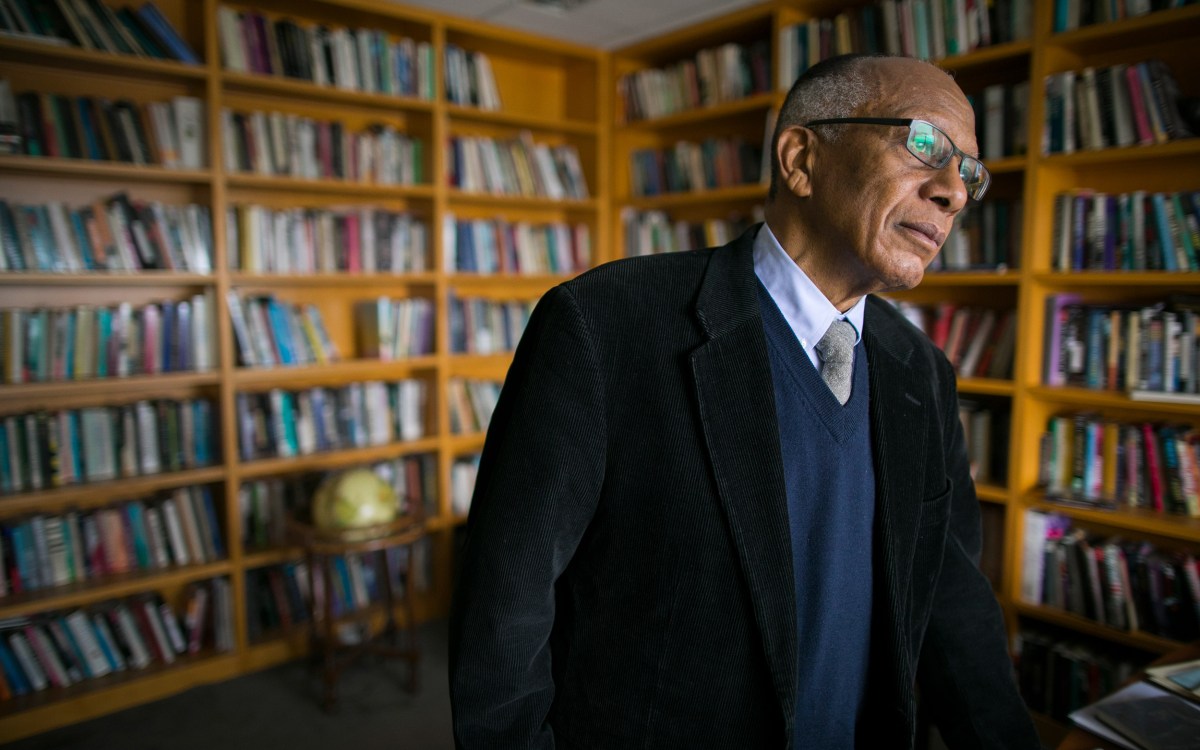

David J. Harris, Ph.D. ’92

Managing Director, Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, Harvard Law School

First, and essentially, we must reckon with what our history has wrought. As difficult as such a reckoning will be to define, indicators will reveal the extent to which we have succeeded. In order to facilitate the process, we must acknowledge a foundational point: “We the People” has never included all of us. That cannot be subject to debate.

Once we acknowledge this defining exclusion, we can trace the myriad ways in which having denied large groups of people, notably African Americans and Native Americans, the most basic rights of membership and participation — the qualities of citizenship — has diminished life chances for individuals and communities. Understanding the real, ongoing harm from policies and practices that have differentially distributed access and opportunity, state violence, and deprivation will open our eyes to avenues for repair and restoration.

We must rethink our notions of justice, as well. Our current coupling of criminality and justice locks us into a fixation on punishment in lieu of a system of justice. I understand justice as being made whole, which promotes practices that center on health and well-being of all residents, and whole communities, as the hallmarks of safety.

Another more tangible indicator of our progress on the pathway to reckoning will be whether we not only hear and empathize with what people who have suffered for decades are saying, but act in truly responsive ways. As people are taking to the streets at great risk to themselves to decry the institutionalized racial violence perpetuated by policing, promoting legislation that bans chokeholds is tone deaf. New York had such a prohibition in place when Eric Garner was murdered. People are not asking for more humane policing, but for a direct reckoning with the culture and institution of policing, including its defunding.

All of our institutions, from government to industry, the academy to the press, must listen more attentively and respond more directly. In reckoning of the horror we have wrought, let us overcome our fear of the word reparations and begin the extensive repair we need.

Brandon Terry ’05

Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies and Social Studies, Harvard University

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

We are in a moment of intense reckoning with America’s history of white supremacy. Millions of Americans appear to be growing more aware of the existential threat that our persistent accommodations to racial domination pose to the future of American democracy. I support a number of the demands of the Movement for Black Lives, including rapid decarceration, billions of dollars of reparative investment in black and Native communities, and shifting economic expenditure from policing and military toward radically reimagined forms of education, health and child care, housing, and public safety. My hope, however, is that we remember that the history of progressive politics in America teaches us that if we do not empower ordinary citizens, especially the most vulnerable, to advocate for and protect such gains, then it is difficult for our achievements to survive beyond moments of intense passion and attention. Such demands should be situated within the call for a strengthened democratic society.

We need, for example, a new Voting Rights Act to resist the Supreme Court’s dismantling of the most effective enforcement provisions of the 1965 act and sustained efforts by Republicans and foreign subversives to suppress voting among working-class, poor, and minoritized racial citizens. The act would subject gerrymandering to nonpartisan review, extend the right to vote to presently and formerly incarcerated persons, radically alter or abolish the Electoral College, grant Washington, D.C., statehood, and study ways to incentivize metropolitan areas (through block grants and other measures) to pursue political integration. We also need legislation that would, in pursuit of economic democracy, dramatically enhance the ability of, and increase protections for, workers to organize, strike, collectively bargain, and pursue reparative action in cases of discrimination. It would also, as Elizabeth Warren has proposed, compel large corporations to have substantial worker representation on their boards, increase antitrust enforcement against growing tech monopolies, and curtail the private domination of public infrastructure (e.g., the internet).

Alan Jenkins ’85, J.D. ’89

Professor of Practice, Harvard Law School

I believe it’s time for a Third Reconstruction: a fundamental reconsideration of our Constitution, systems, institutions, and practices to uphold human rights and ensure equal opportunity for all. Regarding our criminal justice system, for example, this would mean a foundational re-envisioning of what we need to keep all communities safe, prevent harm, and uphold the values of fairness, equal justice, and accountability. We are seeing hints of this, as cities like Minneapolis endeavor to reinvent their public safety systems in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd and ensuing protests. But history shows that real Reconstruction also requires national resolve and federal leadership to enforce and implement substantial, positive change. That seems out of reach in this current moment, but perhaps we can get there together.

Linda D. Chavers, Ph.D. ’13

Lecturer, Department of African and African American Studies, Harvard University; Allston Burr Resident Dean of Winthrop House and Assistant Dean of Harvard College

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

I would love to see policy change on a broad level. I would be happy to hear nothing but silence and see structural changes made in real time. A just society is one that listens to the marginalized more than talks about them — something Harvard does all too well. I’d like to see Harvard add the word “retention” in its language around diversity, inclusion, and belonging. Without that very intentional word the language is just that — language. There is nothing actionable; it only tells us that “we are thinking of you; we are committed to you.” I’m committed to losing 10 pounds, but have I retained that weight loss? Retention means accountability. A just society holds itself accountable to its language. If Harvard included that word policy would have to follow, and we’d be that much closer to enacting real change. “Diversity, inclusion, and belonging” tells us “we want to bring you here.” “Retention” actively says “we will keep you here.” Imagine a world where black folk feel so wanted that Harvard makes sure we want to stay.

Cornell William Brooks

Hauser Professor of the Practice of Nonprofit Organizations; Professor of the Practice of Public Leadership and Social Justice, Harvard Kennedy School

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

My answer centers on the moral specificity of the question, in terms of hashtags, and the stolen humanity of black people in this moment. And that to me means three things, the first of which is defunding policing that does not work and investing in public safety and community health that does work. And there are public policy examples, moral exemplars, around the country where we have defunded carceral responses to community challenges in favor of community solutions. For example, in the state of Massachusetts, we largely defunded children’s prisons in favor of group homes. Number two: Addressing systemic racism, including police brutality, with a deadline. What I mean by that is when it came to peaceful protestors in the streets, they were given a deadline on protest that we call a curfew. But with respect to the injustice that drove them to the streets, there is not yet a deadline. There are those who are talking about addressing police brutality as an inevitability, like the weather, when we should be addressing this with moral urgency — eliminating police brutality by a certain date. It is intolerable and unconscionable that you can have 1,000 people a year die at the hands of the police; one out of every 1,000 black men expects to be killed by police. The sixth-leading cause of death is police brutality. And so, in the same way we impose a deadline on ourselves to develop a vaccine for the COVID-19 pandemic, we should impose a deadline on ourselves to address and solve the pandemic of police brutality. Third, we must appreciate that justice is not merely the absence of injustice, but the presence of an insatiable thirst for justice. Unless we thirst, desire, commit ourselves to seeking justice, injustice is always a threat. Metaphor: Military generals do not assume the presence of peace means the obsolescence of the military. Quite often, we assume the absence of protest means the presence of justice. We assume acquiescence in the streets should mean more quiet with respect to our conscience. And so, I would simply say, as curfews are ending, as National Guardsmen and -women are withdrawn, as protests are becoming more peaceful, this is the time to intensify, to double down, to commit ourselves more fervently to bringing about justice in this country — with a deadline.

Zoe Marks

Lecturer, Harvard Kennedy School

Follow black women leaders. Listen to their wisdom and experience, in the U.S. and globally. Credit and reward their undaunted efforts to achieve collective liberation. In the struggle against oppression, bell hooks teaches us to center those who have been marginalized in society and work against what Kimberlé Crenshaw theorizes as intersectional oppression. Centering black women actually opens our imaginations and focuses our attention on the ways black women have been instrumental in achieving every major step toward freedom in the U.S.’s evolving democracy. They were pivotal in the fight for women’s suffrage, but discriminated against by the movement’s white leaders. They organized the Civil Rights Movement, but have few statues or boulevards immortalizing their efforts. They launched gay liberation, but were marginalized in the push for marriage equality. They made up the majority of the Black Panthers, but their newspapers, community education, and nutrition programs were overshadowed by self-defense units. Throughout American history, others — white women, black men, and white cis gay men and women — have largely gotten credit for the risks black women and queer people took and the expanded rights they achieved for all of us. Like their predecessors, black women leaders in the streets and those heading national organizations in the Movement for Black Lives are articulating ideas that sound radical to those at the center of power. But they make perfect sense if we move to the margins, the intersections, and the communities our current system is designed to suppress. When they say “abolition,” “shut it down,” and “defund,” the concrete action I would like to see others take is to seriously listen to what they tell us is possible. If everyone in our society dedicated just one week of our lives to imagining what structures and services could meaningfully replace institutions that depend on violence and coercion, our moral imaginations would be infinitely sharper. Our willingness and commitment to learning from and celebrating the work of black women would be stronger. And, to invoke Kimberley Latrice Jones, our social contract in turn could become equitable and just.

Mary Travis Bassett

François-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights; Director, François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

While the continued disregard for the lives and basic human rights of black people is embedded in America’s DNA, it is even more difficult to endure this during a pandemic that has disproportionately killed black and Latino people in the U.S. Outrage is not only understandable, it is appropriate. Now more than ever, we must acknowledge the realities of being black in America and stand in solidarity with the black community to drive urgent, systemic changes.

More like this

It is long past time for our country to affirm the values of racial equity, justice, and nonviolence. Now is a time to give credence to ideas that no longer should seem far-fetched. The radical idea to defund, dismantle, and reimagine what public safety means deserves our full attention and support. Why would four police officers show up for one counterfeit $20 bill? And there are immediate steps — banning chokeholds, permitting access to police disciplinary records, among them. As ever, we also need better data on police violence, which are not required to be reported to the public.

As a public health expert, I know that where you live determines a whole host of health outcomes. We should defund police departments and reinvest that funding to improve communities of color, where bad policies have driven generations of deprivation.

It’s also important to look to ourselves and take up the call for institutions, including Harvard, to move beyond the rhetoric of “diversity and inclusion” and become anti-racist. Look at how we spend our money, determine our research priorities, our leadership teams, and our hiring practices, and ask ourselves if we are reinforcing structural racism. Then, we need to do the challenging — but possible — work of dismantling these structures within our own institutions.

Interviews have been lightly edited for clarity and length.