Danger in creating an English-language library in Gaza

Poet Mosab Abu Toha, a Scholar at Risk, describes attempt to intimidate him

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

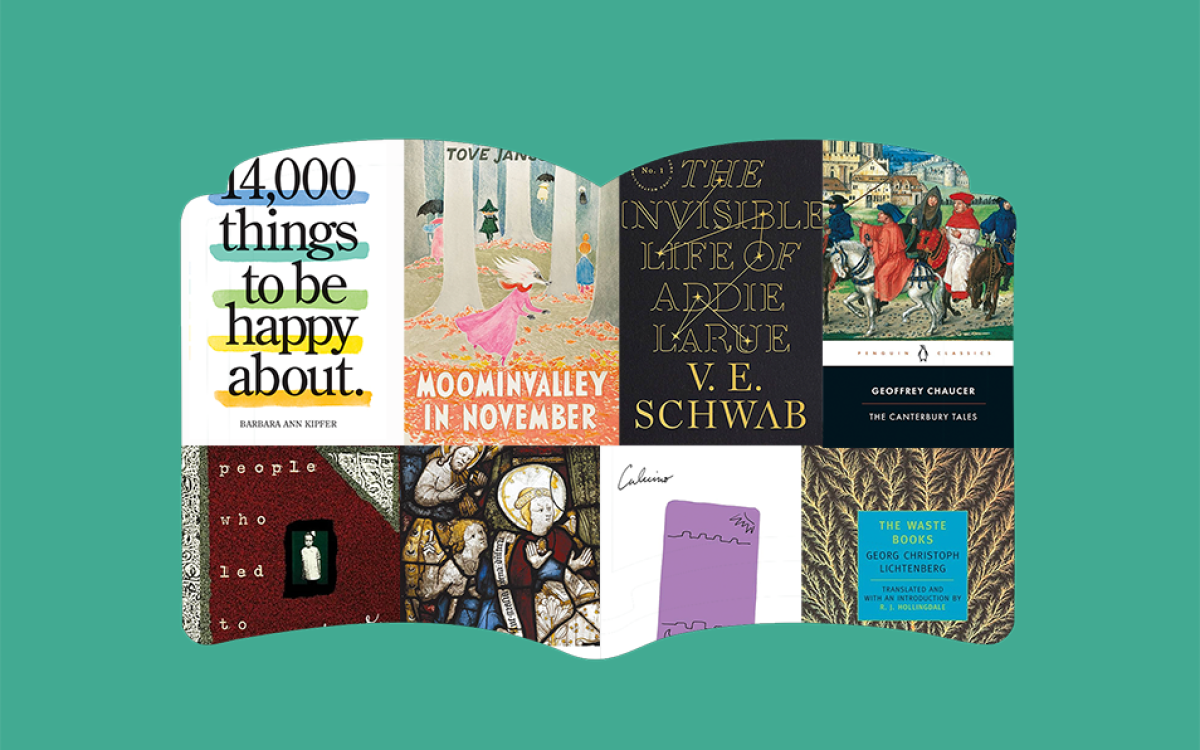

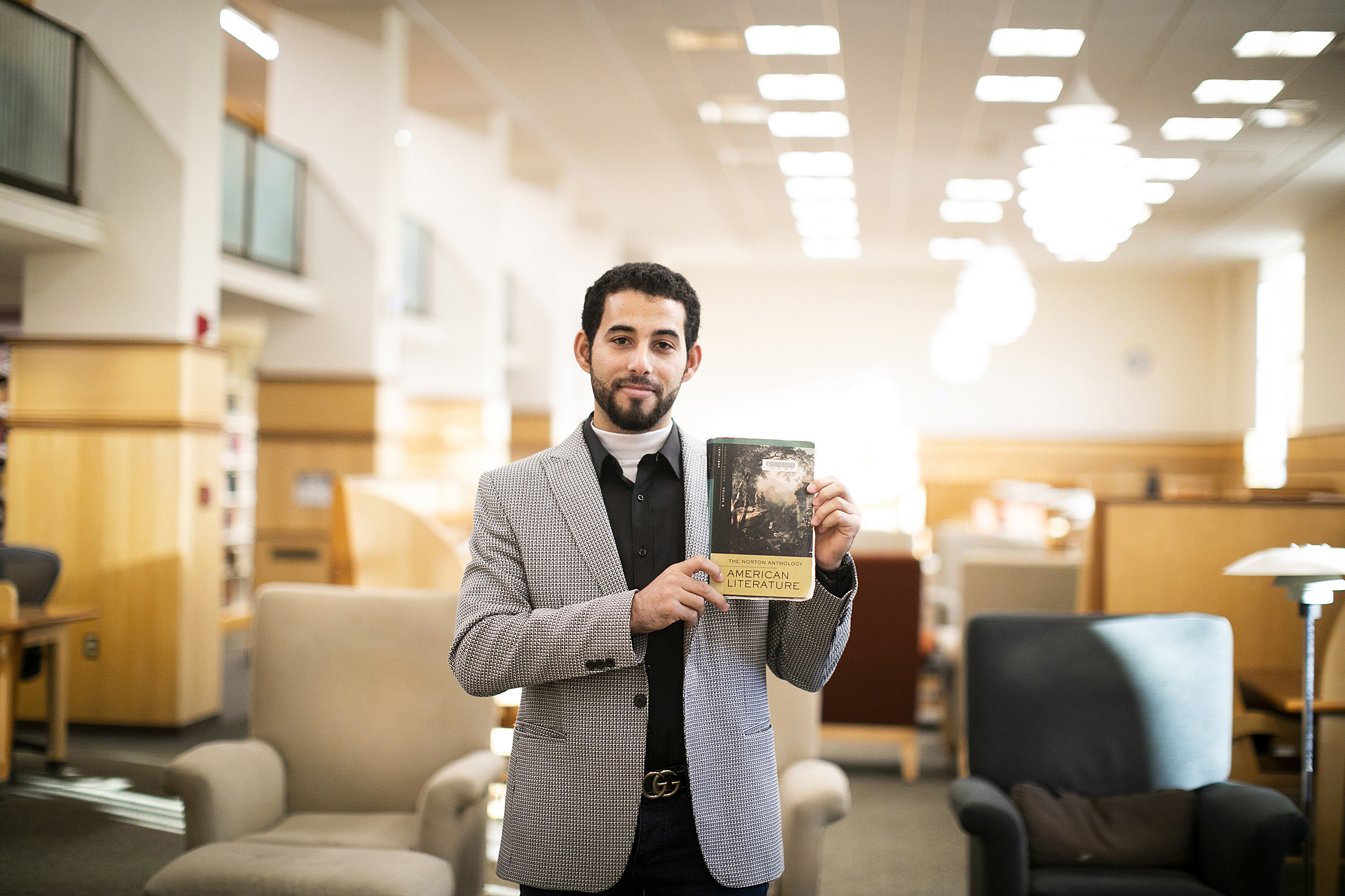

The explosion delayed Mosab Abu Toha’s college graduation. In the summer of 2014 a bomb tore through the Islamic University of Gaza, his alma mater, reducing its English department to shattered concrete and dust.

Abu Toha, an English major and Anglophile, raced to the site to save what he could. “The books were one of the casualties,” he recalled. “I was able to remove ‘The Norton Anthology of American Literature’ from under the rubble.”

But the destruction of the Israel-Gaza Strip conflict didn’t end there. During the several weeks of fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas, another bomb from an Israeli fighter plane — dropped in response to shelling and mortar attacks from Gaza, Israeli officials said — damaged Abu Toha’s house. Three rooms “had their walls opened up like a window that cannot be closed,” he said, “and in one of those rooms was my home library.”

Determined to rebuild his treasured archive, Abu Toha, currently a Harvard Scholar at Risk fellow, turned to the internet, soliciting donations from friends and strangers. Then, as the volumes poured in, an idea began to take shape. Soon he was asking people to contribute books to the first English-language public library in the Gaza Strip, where books, particularly those written in English, can be hard to find. (According to one report, two public libraries have been completely destroyed; five public libraries partially destroyed; and 175 school libraries and 85 private libraries either fully or partially destroyed during the conflict.) In 2017, Abu Toha’s library opened its doors.

The damage at the Islamic University of Gaza after it was hit in an overnight Israeli strike.

Sipa via AP Images

But he wasn’t finished.

“Six months later I started a second fundraising campaign to rent a bigger place and buy more shelves and furniture for the growing library,” he said. In 2019 the second branch of the Edward Said Library opened in Gaza City. Its name honors the Palestinian American academic, political activist, and literary critic who received his master’s and doctorate from Harvard, where he specialized in English literature, in 1960 and 1964.

Said, who died in 2003 from cancer, “is a role model for many people. He is a guru. And because he was someone who lived in America, but he never forgot the suffering of his people, this is something I admired in him.”

Many have admired Abu Toha’s efforts, including literary luminaries such as American linguist, philosopher, and activist Noam Chomsky and the American poet, essayist, and critic Katha Pollitt, who have donated their own books to his cause, as has Said’s widow, Mariam. Chomsky called Abu Toha’s library “a unique resource … and a rare flicker of light and hope for the young people of Gaza.” Today his branches house more than 4,000 books and offer a range of classes and programs for children and adults.

“When people come and read and meet each other and attend some musical events, some art activities, that will change their mood, how they feel, so it’s a kind of refuge for them,” said Abu Toha. “This is what I believe a library should be. This is also an opportunity to connect Gaza with the world.”

For years, reading and studying English literature offered Abu Toha, whose travel beyond Gaza has been largely restricted, a window onto new worlds. He credits his love of language to an early college professor who “saw a spark” and encouraged him to write. “He was like a father advising his son, and I wanted to honor his belief in me,” said Abu Toha, who considers himself “more creative writer in English.”

Mosab Abu Toha opened the first English-language library in the Gaza Strip in 2017. In 2019, the second branch of the Edward Said Library opened in Gaza City. Edward Said (portrait on wall) received his master’s and doctorate from Harvard in 1960 and 1964.

Courtesy of Mosab Abu Toha

After graduating from college with an English degree he taught in Gaza schools run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. He also began writing poetry. With his words Abu Toha said he tries to “develop an image for the reader. It’s the best way to express how I feel and how I live. It’s like filling the gap for me.”

He lists the English poet William Wordsworth, the revolutionary Iraqi poet Ahmed Matar, the Palestinian author and political activist Ghassan Kanafani, and the man who was widely regarded as the Palestinian national poet, Mahmoud Darwish, as key inspirations. (Abu Toha often signs his emails with a line by Darwish: “Poetry and beauty are always making peace. When you read something beautiful you find co-existence; it breaks walls down.”)

But co-existence in Hamas-controlled Gaza became more complicated for Abu Toha after his first library opened its doors. In August 2018 he was summoned to appear before Hamas authorities. He arrived early for the appointment eager to clear up what he assumed was an administrative mistake, only to be blindfolded, interrogated, and beaten — retaliation, he believes, for his library efforts.

Mosab Abu Toha holds a copy “The Norton Anthology of American Literature,” a book he saved from the University of Gaza after a bomb exploded on site.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

At the urging of a friend, Abu Toha applied to Harvard’s Scholar at Risk program. In Cambridge he is being hosted by Harvard’s Comparative Literature Department; he is also supported by Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies, and is a Religious Literacy Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and a Visiting Librarian in Residence at Houghton Library. During his fellowship, he is working on a book of poetry and hoping to connect with anyone interested in learning more about his work and life.

“I am here for people to know if they want. Of course, anyone who asks about Gaza I am willing to talk and to express everything that I feel about being a Gazan,” said Abu Toha, adding, “it’s about learning also. I learn a lot from people here and I am also starting to develop a new picture of how the relationship should be between the West and the East.”

Unsurprisingly, in his small office on the top floor of Warren House another mini-library has already taken shape. A handful of shelves contain the Said titles he brought with him from home, along with books given to him by Stephen Greenblatt, John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities, including some of Greenblatt’s own writings and some by Elizabeth Bishop, Shakespeare, Sophocles, and others.

It’s also no surprise that whenever he has a spare moment, Abu Toha can be found wandering the stacks in Widener Library, with its collection of 3.5 million volumes.

“We don’t have a library like this in Gaza,” he said. “It’s a paradise for a book lover.”