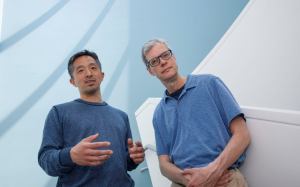

Postdoc fellow Nicholas Holowka (pictured) measures calluses with an ultrasound. Holowka and Professor Daniel Lieberman are studying the benefits attached to calluses.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Leave those calluses alone

A groundbreaking researcher in running turns his attention to walking, with and without shoes

Daniel E. Lieberman doesn’t hate shoes. The Edwin M. Lerner II Professor of Biological Science and chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology wants to clear that up right away.

“There has been debate about barefoot running being good or bad, or shoes being good or bad, and this is the wrong debate,” Lieberman said. “It should be about what the costs and benefits of shoes are and how we can better understand how shoes affect our feet, our health, the way we walk.”

He should know.

Since Lieberman published his groundbreaking study, “Endurance running and the evolution of Homo,” in Nature in 2004, researchers across the globe have studied the biomechanics of running, particularly as it involves bare or shod feet. But, oddly, few have considered walking, the primary mode of transportation humans have used to get from Point A to Point B over the past quarter of a million years.

Now comes Lieberman with his latest paper, which has just been published in Nature. This time he explores the value of the calluses we develop while walking barefoot, finding them to be a marvel of natural selection’s ability to engineer without trade-offs.

Most people are aware of how developing calluses protects skin. Common sense would suggest that there is a price to be paid in lost sensitivity. Not so, say Lieberman and his collaborators, who found no matter how thick, tough, and crusty the skin on the bottom of walkers’ feet became, they could still feel the ground as well as someone with virtually no calluses.

“We live in this weird world where calluses are bad … But until recently it was abnormal not to have calluses,” said Professor Daniel Lieberman.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“We tested the sense of touch, the dynamic sense of what you feel on the ground. We found these stiff calluses don’t prevent any communication between the force of the feeling of what you are stepping on and what makes its way to the nerve cell to be transmitted to your brain,” said Nicholas B. Holowka, a postdoctoral fellow in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and lecturer in Human Evolutionary Biology. Holowka shares first-author credit on the study with Bert Wynands of Germany’s Technical University of Chemnitz.

To study habitually barefoot walkers, Lieberman and members of his lab joined their German collaborators in Kenya, where they worked with Professor Robert Ojiambo of the University of Global Health Equity and orthopedic surgeon Paul Okutoyi of Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital. In a rural town in the western part of the country, the team studied the feet of people who never wear shoes, then compared them with the feet of a similar demographic of people from a nearby city who are typically shod.

Technical University of Chemnitz Professor Thomas Milani, the lead scientist from Germany and an expert on how sensory perception affects gait and foot function, said his team meticulously calibrated and adapted their instruments for the study to guarantee the testing equipment’s validity and reliability. Their devices and observations not only confirmed that calluses didn’t interrupt the sense of touch, but that people with thick calluses didn’t walk any different than people with thin ones.

Comparing the foot of a shoe wearer vs. the barefoot walker. In Kenya, researchers measured the biomechanics of the barefoot walker.

Photos by Thomas Milani and Daniel Lieberman

This wasn’t true, however, for shoe wearers. The study found that they had heavier foot strikes than their barefoot counterparts. The researchers don’t know what this extra force does to the body over a lifetime of wearing sandals or sneakers, but they wonder whether and how it relates to increasing rates of degenerative joint diseases such as osteoarthritis.

Lieberman and Holowka returned to Boston to conduct more research using a local cohort of barefoot enthusiasts. The results backed up their findings in Kenya: Calluses serve a unique function and aren’t nuisances to be scrubbed away during a pedicure.

“We live in this weird world where calluses are bad, like you have a problem with your shoe, and you go to a podiatrist, and they remove them,” Lieberman said. “But until recently it was abnormal not to have calluses. We’ve lost touch with our bodies in some respects and this is a good example of that. When we tell our results to barefoot people, they say, ‘Tell me something I don’t already know.’”