“It’s about the Bible and how religion shaped ideas of slavery or antislavery,” says Alexandrea Harriott (right) about “The Yoke of Bondage: Christianity and African Slavery in the United States,” on view at Andover-Harvard Theological Library through March 15.

Photos by Olivia Falcigno

Slavery alongside Christianity

Student exhibition probes ties, tensions between them during American bondage

In the modern era, Christianity and slavery are seen as oxymoronic. But for much of Christian history, many saw no conflict between keeping the faith and keeping or trading slaves. From the first century until the Civil War, the Bible itself was often used to justify slavery.

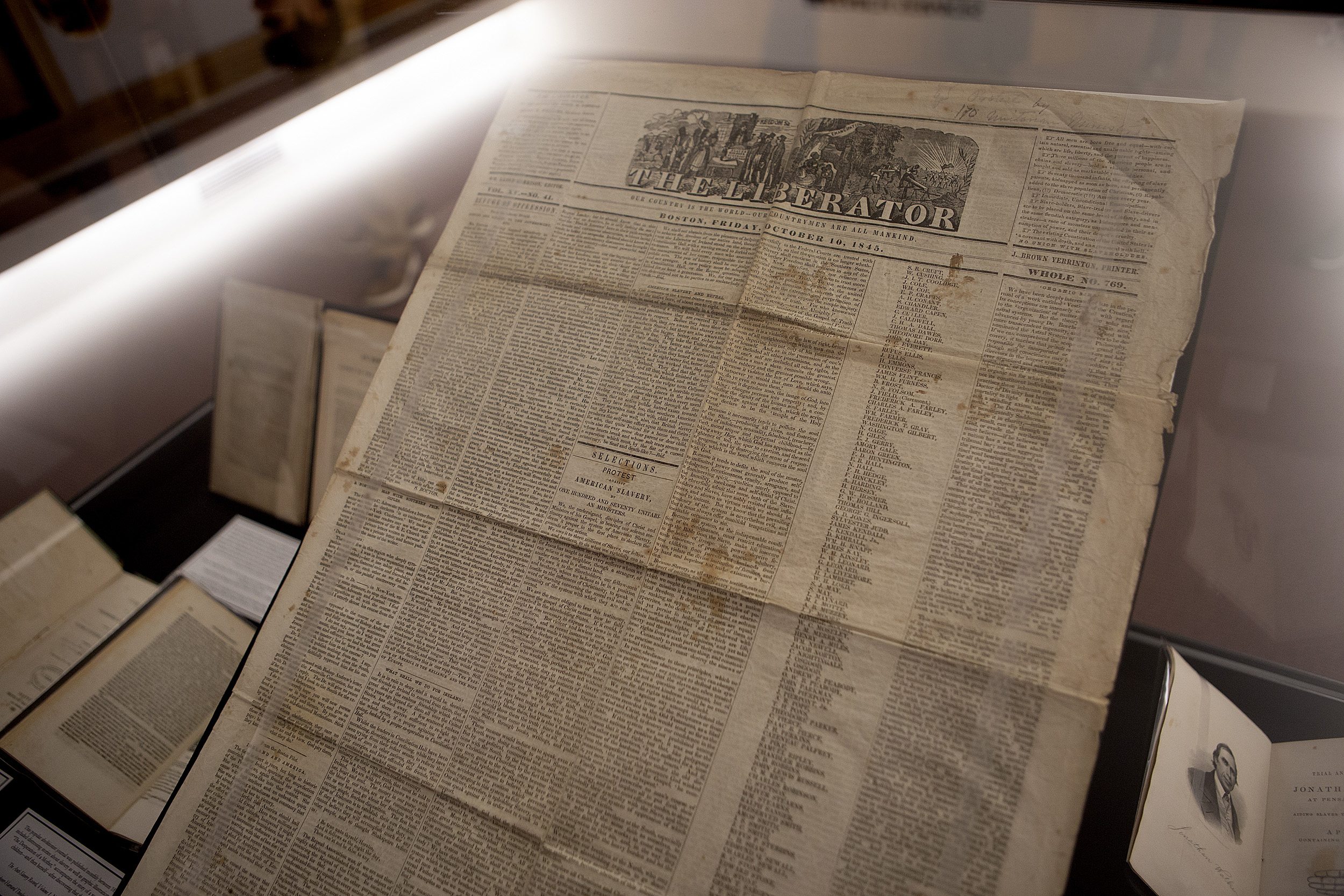

That unsettling relationship is the focus of an exhibit at Harvard Divinity School’s Andover-Harvard Theological Library. “The Yoke of Bondage: Christianity and African Slavery in the United States” features more than 20 documents, including rare books, that range from 1619, when the first slaves were brought to Virginia, to the Civil War’s end in 1865. The texts analyze the debate during that period among Christian theologians, authors, and adherents who either justified slavery or stood against it.

While it has the thorough look and feel of a professionally curated exhibit, “The Yoke of Bondage” was organized and put together by the 10 students taking “Christianity and Slavery in America, 1619‒1865,” a first-year College seminar.

“The relationship between Christianity and slavery was not an easy one,” and affected more than just the church, said Seven Richmond, one of the students in the seminar. “This debate carried over to politics and economic issues that really were an inspiration for the whole Civil War. I think it’s important to realize the impact and importance of religion and how religious disagreements can lead to broader disagreements in a whole political climate.”

On view through March 15, the exhibit includes pamphlets, sermons, abolitionist speeches, poems, and personal religious narratives of enslaved men and women. The works are laid out by theme in four cases, with the writings of black Christian authors at the center. That case gives voice to former slaves such as Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, and Phillis Wheatley, a slave in Boston who became the first published African-American female poet and was emancipated shortly after her first book appeared. In the other cases are works by authors who used biblical passages to support their positions on slavery and works by supporters of the antislavery and abolitionist movements, including an anonymous pamphlet assuring readers that good Christians could own slaves.

“We definitely look at both sides,” said Alexandrea Harriott, another student in the seminar. “It’s definitely about the Bible and how religion shaped [the authors’] ideas of slavery or antislavery, and dissecting what they were thinking and how they proved their ideas.”

Abolitionist publications such as Maria Chapman Weston’s “The Liberty Bell” and The Liberator newspaper are displayed alongside works using biblical passages to justify slavery.

To create the exhibit, the students discussed and researched texts assigned by Catherine Brekus, the Charles Warren Professor of the History of Religion in America at Harvard Divinity School, to decide which to feature and in which theme they fell. Each student also selected a work to research individually.

One work that made the cut was Angelina Grimke’s “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” a biblical argument against slavery that was published in 1836. Grimke, who grew up in the South as part of a wealthy, slaveholding family, rejected her upbringing and moved to Philadelphia with her sister, where they joined the Anti-Slavery Society and published pamphlets defending the equality of women and slaves.

“She was trying to get at people whom she shared a common background with to try to persuade them … that she knows where they are coming from,” said first-year Kyra Teboe. However, she said, “The pamphlet was burned because not only was [Grimke] promoting abolitionism in the South, but she was also promoting more of a radical political cause as a woman, and that was itself problematic at the time.”

Another work on display is Josiah Priest’s “Slavery, as it Relates to the Negro, or African Race.” Published in 1843, the book defends slavery using narratives from the Book of Genesis. Priest argued that God created black people to be slaves, citing Noah’s curse on his son Ham, who Priest claimed had black skin.

“It was quite the read,” said Richmond, who chose the book. “When I think of Noah, I think of Noah’s Ark and the flood. I don’t think of how Noah would be used to justify slavery in America. That was something that was really different for me.”

Setting up the exhibit was a part of the seminar, to give the students start-to-finish, hands-on experience. They had guidance, of course. Brekus, staff members from special collections in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, and staff from the Weissman Preservation Center attended opening day as students added Velcro to the backs of posters that needed to be hung, made cradles to display the texts, and placed the texts in the displays.

“This is the nitty-gritty of putting up an exhibit,” said Brekus, who is also chair of the Committee on the Study of Religion.

The students made most of the decisions about the exhibit’s arrangements, including how to place a series of introductory posters and how to display smaller items. For Luca Hinrichs, that meant deciding what to display from Maria Chapman Weston’s “The Liberty Bell.” In the end, he left the book closed to show the Abolitionist Bell stamped in gold foil on its cover.

In addition to the topic, the students said they were attracted to the seminar by the chance to take a class structured quite differently from most. Harvard’s Freshman Seminar Program was formally established in 1963 to let first-year students try a pass-fail class with a small number of students, usually not more than 12.

“The hope is that students can really focus on enjoying the learning and getting to know other freshmen without the pressure of grades,” Brekus said.

For Mason Arbery, that was appreciated. “I really like the aspect of being in a small setting,” he said. Behind him, a group of his classmates joked with one another as they closed the top of one of the display cases. “Obviously, you can tell we’ve gotten to know each other pretty well.”