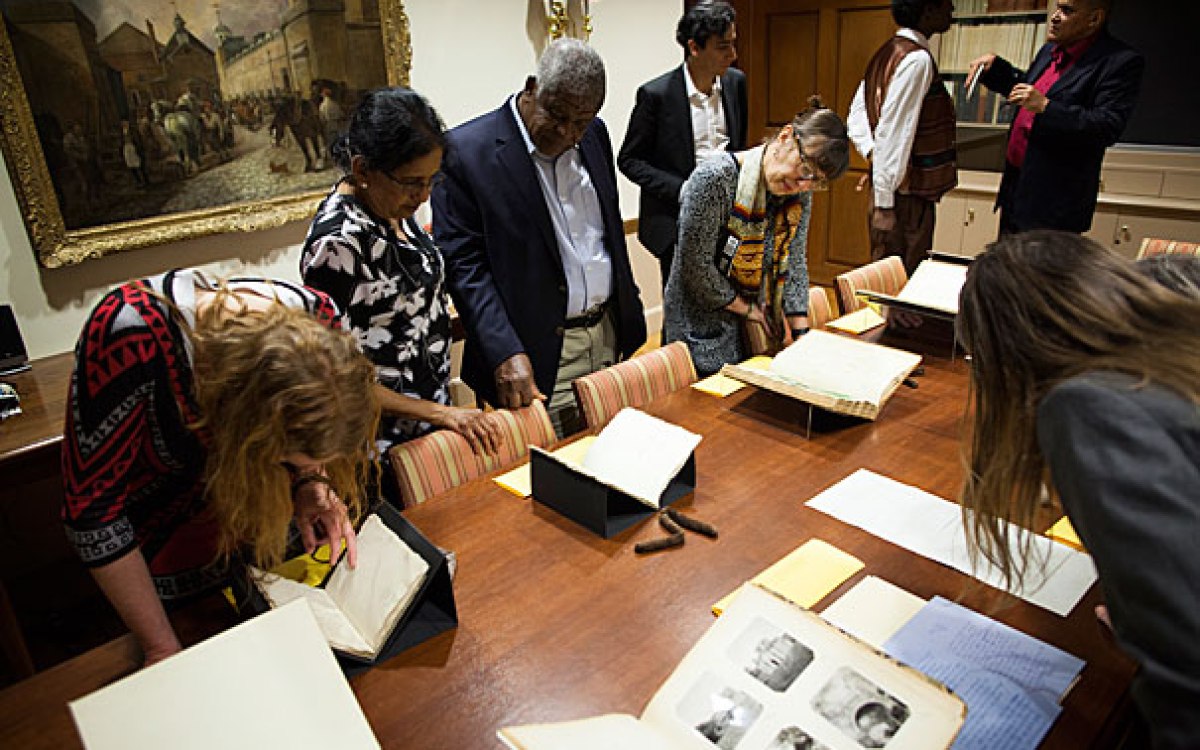

Zelalem Kibret, a scholar at risk this year at Harvard, was arrested and jailed by the Ethiopian government in 2014 for his dissident activity as a part of the Zone 9 blogging collective.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Speaking up, reaching out

Ethiopian scholar at risk uses blog to push for justice at home

Six years ago, Zelalem Kibret’s activism prompted him to visit prison; less than two years later, it landed him inside.

A lawyer and then-professor of law at Ambo University in Ethiopia, Zelalem first visited a jailed politician in the infamous Kaliti Prison in 2012, hoping to raise awareness about people arrested for challenging the status quo. In 2014, Zelalem himself was behind bars for speaking up.

That year, as part of a blogging collective called Zone 9, Zelalem and his colleagues, seven men and two women in all, had organized online campaigns urging the government to honor the rights promised in the country’s constitution. The group — two attorneys, a mathematician, an economist, an engineer, a journalist, and three information technology experts — met with jailed journalists and politicians, called for freedom of expression and an end to the torture of political detainees, and asked Ethiopians to share with them their hopes and dreams for their country. The effort angered government officials, Zelalem said.

“We are not asking for this law to be repealed, this law to be passed. Just respect the constitution. Fortunately, we have a very wonderful constitution, but no one cares about it,” said Zelalem on a recent afternoon at Harvard, where he has been a Scholar At Risk, supported by the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

Zelalem knows firsthand Ethiopia’s record of human rights abuses. In 2012, he said, he was grabbed off an Ambo street by members of the National Intelligence Security Service, who locked him in a small room and interrogated and tortured him for hours. “Why was he criticizing the government?” and “Who was sponsoring his subversive activities?” he recalled his captors demanding. They repeatedly threw him to the floor, whipped him with a power cable, and beat his knees with the butt of a pistol, said Zelalem. When he was released, bruised and bloodied, he couldn’t walk for days.

“It was so terrible.”

But it wasn’t uncommon. Growing up in Ethiopia, Zelalem had long been cautioned about speaking out. “You have to be careful,” warned his parents, who had friends killed or exiled during the nation’s brutal communist dictatorship that lasted until 1991. As such, they were hesitant to express their political views.

But certain influences planted an early seed of curiosity in their son. Ethiopia’s longstanding ties to the Soviet Union meant Zelalem’s boyhood home was populated with Russian literature translated into Amharic. Works by the likes of Nikolai Gogol and Leo Tolstoy filled the family bookshelves, along with a Marxist dictionary — “a world book from the communist point of view” — with descriptions of political, economic, and philosophical ideologies. His older brother, also a lawyer, fueled his interest in learning. But it was a contested election in 2005, the year he turned 18 and was first eligible to vote, that made Zelalem’s interest in politics really take hold.

“We all can talk now; we can all be journalists.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

While government officials had pledged their commitment to democratic reforms, members of the opposition party, as well as various human-rights organizations, complained of voter fraud during the election and contested the results. Security forces clashed with student protestors. Close to 200 demonstrators were killed, and hundreds more arrested.

It was “eye-opening,” recalled Zelalem, a “milestone for me and many of my peers.”

Watching friends and fellow students arrested for simply speaking up inspired him to get involved with the Ethiopian Human Rights Council, a nongovernmental organization that documents rights abuses. Later, while working as a legal consultant and analyst, he read stories in Addis Neger, the Ethiopian newspaper that he said was known for its balanced reporting and well-sourced articles. The articles sparked a desire to put his own thoughts on the page, and so he began. When the government shut the paper down, Zelalem turned to the web, launching his personal blog in 2011.

He realized then that “we all can talk now; we can all be journalists.”

Together with friends he met online, he visited a journalist jailed in Kaliti Prison for speaking out. She explained that the prison had eight zones, and that prisoners referred to life beyond the bars as zone nine because of the shrinking civil rights and liberties throughout the country. The bitter inside joke gave the bloggers their name.

After two years of having their web site repeatedly shut down and being harassed and followed by government officials, six of the nine were arrested and sent to jail. They were charged with “outrage against the constitution” and terrorism under the country’s expansive anti-terrorism law, he said. Zelalem was released just weeks ahead of President Barack Obama’s visit to the country, more than a year after his arrest. In 2015, when Zone 9 won a citizen journalism award, government officials seized Zelalem’s passport and refused to let him travel to Paris to accept the honor.

He got it in time to participate in the Obama-sponsored African Leadership Initiative fellowship in 2016, studying at the University of Virginia and the College of William & Mary. Last year he took part in a fellowship at New York University’s Center for Human Rights and Global Justice. He arrived at Harvard this past fall.

In Cambridge with his wife and young son, Zelalem has been studying the impact of “liberation technology” on new social movements in sub-Saharan Africa.

“I am looking at how these new technologies are enabling [social movements] to push forward.”

He is also exploring writing a book on how torture affects the lives of political prisoners. Next up is a fellowship at McGill University in Canada, where he will continue his research and writing and use his voice against injustice.

“I am always hopeful,” he said. “I hope that things will be better eventually.”