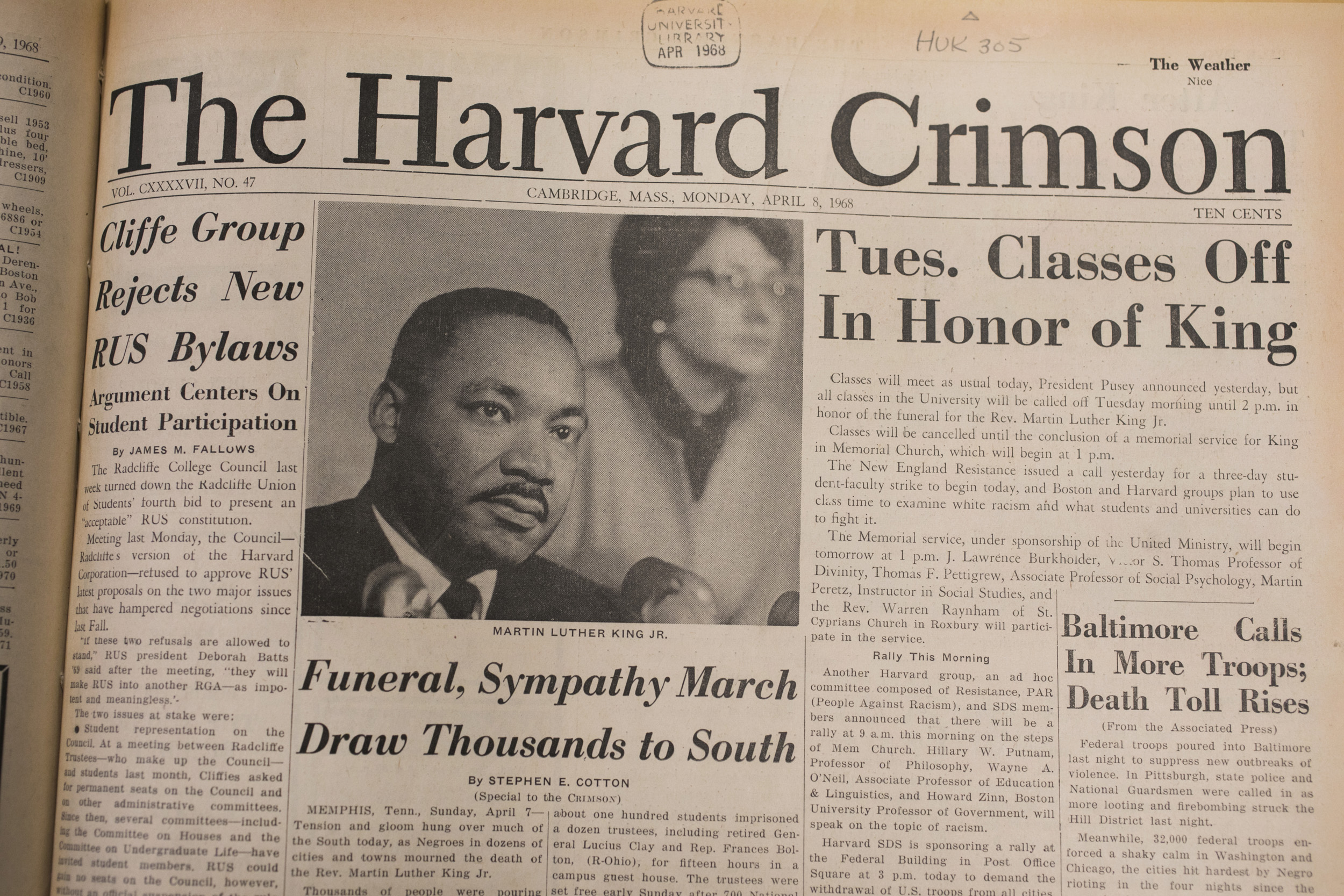

The Harvard Crimson’s April 8, 1968, edition.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Losing King: Shock, sorrow, anger, and a voice time hasn’t silenced

Five decades after assassination, views from Gates, Gordon-Reed, others on the nation then and now

Fifty years ago the murder of a Baptist minister turned Civil Rights giant shook the nation. Just after 6 p.m. on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn. There to support the city’s striking sanitation workers, King was about to head to dinner when he was struck in the jaw by a single bullet. In a country already roiled by racial violence and civil unrest, the killing set off a wave of deadly riots from coast to coast.

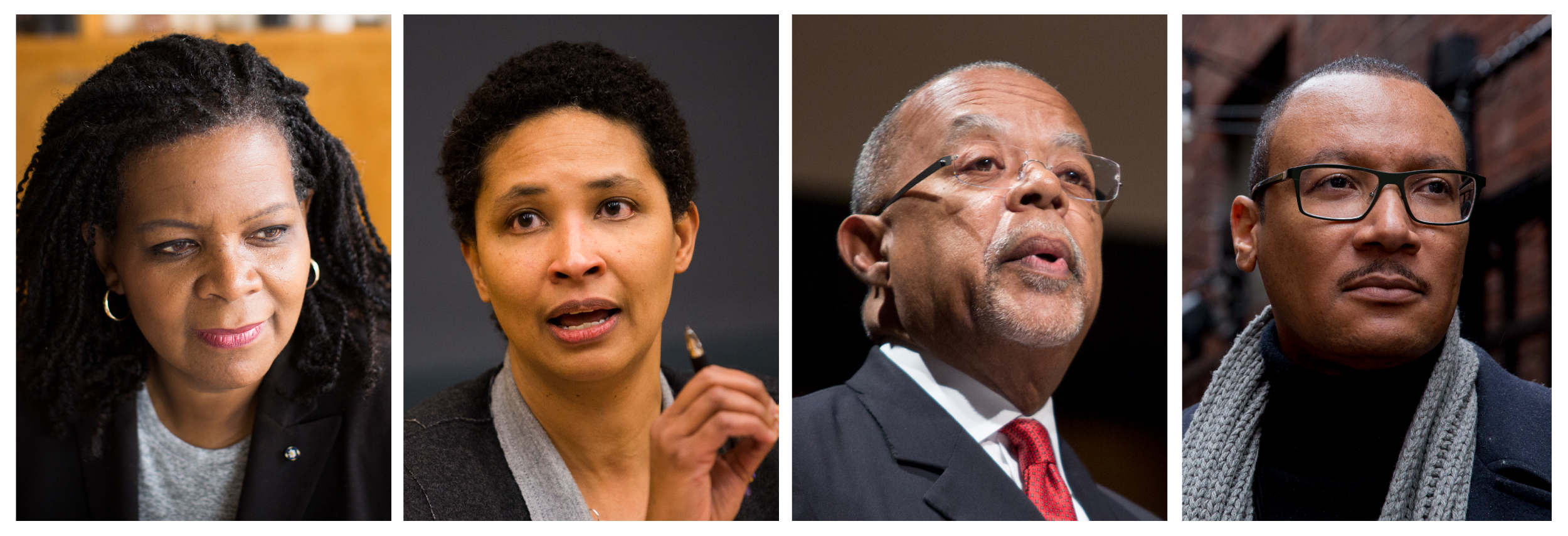

We asked a group of Harvard scholars to reflect on King’s life, death, and legacy. Historians Annette Gordon-Reed and Henry Louis Gates Jr. recalled where they were when they heard about the assassination. Philosopher Tommie Shelby remembered his earliest impressions of King’s language and rhetoric. All three shared thoughts on how the Civil Rights leader would view today’s America. Political theorist Danielle Allen, set to deliver the keynote at a King-focused conference on Friday, said that 50 years on, his work remains unfinished.

Annette Gordon-Reed (from left), Danielle Allen, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Tommie Shelby.

File photos by Stephanie Mitchell and Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff

‘It’s a shock that I’ve never gotten over’

A senior in high school, Gates was at home in Piedmont, Va., watching TV when an announcement interrupted the news.

“I had three best friends that were black and they came over and we were just shocked — we were stunned,” said Gates, the Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center. “There was nothing that we could do.

“Basically it’s a shock that I’ve never gotten over, really. I mean, I still can’t believe it when I watch the footage.”

The shock lingered in Gates’ voice as he considered King’s relative youth.

“He seemed like such an old man but he was 39 years old. He did all of that when he was 39, and I definitely believe — I am one of the black people who thinks there was some kind of conspiracy to kill him. I think he could have been the first black president and I don’t think America was ready for that.”

King, Gates added, was “moving toward an amalgamation of race and class and that was threatening to the system.”

What would he think of the U.S. today?

Gates said King would be surprised by how much the country has moved the dial, and stunned by the numbers of upper- and middle-class African-Americans. “But he would be equally shocked that the percentage of black children living at or beneath the poverty line is roughly the same as it was in 1970, roughly the same as it was when he died.”

And while King would be pleased by the progress made since 1968, and “astonished and delighted” that the country was led by an African-American president for eight years, he would also be dismayed “at mass incarceration” and at “deindustrialization which interrupted the cycle of moving from the working class to the middle class and the middle class to the upper-middle class.”

‘It was clear that he was making lots of people angry’

Gordon-Reed, 9 years old in 1968, was with her mother at the home of one her friends “when her son came into the room and told us that King had been assassinated.”

Her Texas community’s reaction was one of “great sadness,” said Gordon-Reed, Harvard Law School’s Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History, a professor of history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and a Pulitzer Prize winner for “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family.”

“But this was a small town with a small black population,” she said. “More open anger was expressed in urban communities.”

Gordon-Reed said her mother and father “were not surprised” by King’s murder. “It was clear that he was making lots of people angry. The possibility of violence was always present given all that was at stake.”

Her parents’ reaction was likely shared by countless Americans. King had endured repeated physical attacks during his years of nonviolent protests, and death threats against him were common. In his last public address, delivered at Memphis’ Mason Temple the day before his death, King alluded to his own mortality.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Turning to today, Gordon-Reed said King would have been amazed by the Obama presidency, though unsurprised by the backlash against it.

“I would imagine he may also be surprised at how he has been embraced by so many different segments of society, for their own purposes,” she added, and “by the pace of social changes — the women’s movement, the movement for LGBTQ rights. And [that] the issue of race is not just a matter of black and white anymore.”

While much has changed for the better, Gordon-Reed said the economic advances King pressed for at the end of this life “have not come to fruition.”

“All available evidence indicates that communities of color still lag behind in terms of wealth,” she said. “The legacies of slavery, segregation, and the commitment to white supremacy have not yet been overcome. In fact, the issue of inequality is not just about race. The situation of organized labor — the weakening of unions overall — would have surprised him, I think. He thought that unions, along with working-class people of all colors, could cooperate to strike a blow on behalf of all marginalized people. That does not seem to be on the horizon.”

‘Leaders should not seek riches, fame, or even recognition for their efforts’

One of Shelby’s most powerful King moments was the first time he read “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

“It has so many important ethical lessons,” said the Caldwell Titcomb Professor of African and African American Studies and of Philosophy. “For instance, King argued that it is wrong to counsel the oppressed not to fight for their rights because this might provoke others to engage in violence or might create social strife. ‘Law and order’ and civil peace are not ends in themselves. They are means for establishing and maintaining just social conditions.”

Which of King’s beliefs would most surprise people today? Reparations are high on Shelby’s list.

In “Why We Can’t Wait” (1964), King wrote that while the cost made it “impossible to fully pay reparations to blacks for all the wrongs of slavery … compensation was due to the descendants of slaves for the unpaid toil of their ancestors.”

And King’s life still contains crucial lessons for those in charge today, said Shelby, co-editor of “To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr.”

“Leaders should not seek riches, fame, or even recognition for their efforts,” Shelby said. “They should see their vocation as one of service and sacrifice and should lead by example. This kind of leadership requires integrity, resilience, a willingness to speak hard truths in public, and most of all hope — the conviction that, through our determined efforts, we can make our world more peaceful and just.”

‘Courage, endurance, moral clarity, and love’

With Harvard students on spring break the week of the assassination, King was remembered on Palm Sunday at Memorial Church. The Harvard Crimson’s Monday, April 8, edition ran a picture of the slain icon accompanied by an article headlined “Funeral, Sympathy March Draw Thousands to South.” The following day, President Nathan M. Pusey canceled morning and early afternoon classes to allow students to attend a special service in Memorial Church. The Harvard leader addressed the crowd during the somber ceremony.

“I do not know when the death of a private citizen has quickened such a universal response of grief and deprivation — nationwide and worldwide,” said Pusey. “Our grief is for the man and for the many unaccomplished things for which he worked and died.”

The impact of King’s death rippled through Commencement events. In March 1968, students had broken from tradition and directly invited the Class Day speaker. They selected King, whose speech, set for June 12, was expected to address the Vietnam War.

A year earlier King had registered his opposition to the conflict in a blistering New York speech that connected war, racism, and poverty. Congressman John Lewis of Georgia was in the audience that day. “I heard him speak so many times,” Lewis told The New Yorker in 2017. “I still think this is probably the best.” (In a fitting turn, Lewis will be the principal speaker at the Afternoon Program of Harvard’s 367th Commencement on May 24.)

Her husband’s death still raw, Coretta Scott King agreed to speak in his place on Class Day. By then the nation was mourning another loss. Six days earlier Civil Rights advocate and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy had been shot to death in Los Angeles.

“These two men addressed themselves to the burning issues of our times: They spoke out against great evils in our society: racism, poverty, and war,” King told seniors at Sanders Theatre. “They were great and effective actors on the stage of history. They played their parts exceedingly well, thus inspiring millions. They are a part of that creative minority which helped to move society forward.

“As young people, as students, your lives have been greatly affected by the loss of these champions of freedom, of justice, of human dignity and peace. In a power-drunk world, where means become ends, and violence becomes a favorite pastime, we are swiftly moving toward self-annihilation. Your generation must speak out with righteous indignation against the forces which are seeking to destroy us.”

Five decades removed from the grieving widow’s show of courage and resolve, Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor, will focus her address at Friday’s symposium on urging the same qualities upon a nation still struggling to live up to Martin Luther King Jr.’s highest hopes.

“The Civil Rights movement is far from done; the onward march of freedom still requires courage, endurance, moral clarity, and love,” Allen said. “I think we can best memorialize the men and women who worked with King, and King himself, by finding the courage to insist, over and over again and lovingly, on the ethical demands of full integration.”