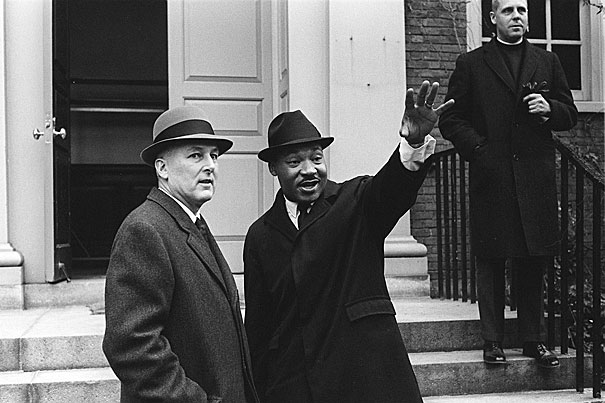

A January visit in 1965 shows Martin Luther King Jr. with Nathan M. Pusey (left), Harvard’s 24th president, and the Rev. Charles P. Price on the steps of Appleton Chapel. The visit came just two months before the televised violence of the protest march in Selma, Ala.

Photo courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

When King came to Harvard

Returned often in campaign for civil rights, as guest preacher

Martin Luther King Jr., the martyred civil rights icon whose national day of commemoration is Monday, was no stranger to Harvard University.

He attended classes as a special student in 1952 and 1953, taking philosophy courses on Plato and on Alfred North Whitehead. His grade report showed a B and an A-, respectively.

King also was a guest preacher at Harvard’s Memorial Church during the 1959-1960 school year, the first in a string of visits to the University’s chief pulpit. By then, the reverend was already four years into a civil rights career that had begun with the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. In 1957, King had helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and become its first president.

His ties to New England, of course, go beyond Harvard. In 1955, King earned a doctor of philosophy degree in theology at Boston University, where theologian and educator Howard Thurman had introduced him to the Indian leader Mohandas Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent resistance. (The pacifist Bayard Rustin, though, was later King’s primary tutor on the ways of Gandhi.)

In October of 1962, the 33-year-old activist minister delivered a lecture at Harvard Law School (HLS), with “The Future of Integration” as his topic. (That same year, HLS hosted speeches by the Rev. Billy Graham and the labor leader Jimmy Hoffa.) That day, King hewed firmly to the idea of “nonviolent direct action,” calling integration a matter of struggle, and not an artifact of official policy — “not some lavish dish,” he said, “that the federal government will pass out on a silver platter.”

King also used his speech to call for legislative action. “The law cannot make a man love me,” he said, “but it can keep him from lynching me.” (The Civil Rights Act of 1964 came two years later.) Six months after the lecture, King was held in a Birmingham, Ala., jail. Ten months later came the March on Washington, and the “I Have a Dream” speech, and less than six years later, his assassination.

But of all the visits paid to Harvard by King, perhaps the most famous took place on Jan. 10, 1965, just five days before his 36th birthday. That October, King had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the youngest person to get the award. He had been invited to be guest preacher at the Memorial Church on that snowless, chilly Sunday morning. King’s sermon was part of a one-day whirlwind visit to the Boston area. Later, in the evening, he delivered a talk around the corner from Harvard Yard, to a full hall at what was then Rindge Technical School on Cambridge Street.

King’s student-sponsored January visit to Harvard, which came just two months before the televised violence of the protest march in Selma, Ala., was captured in a series of images by a photographer at what was then the Harvard University News Office. Image 6A of a contact sheet now at the Harvard University Archives provides the best-known picture of the visit. In black and white, a smiling King, bundled up in a dark overcoat and wearing a short-brimmed hat, waves to an unseen crowd of admirers. To his right, hands pocketed and wearing a pale fedora, is Nathan M. Pusey, Harvard’s 24th president (1953-1971). Famous for his earlier clashes with Red-baiting Sen. Joseph McCarthy, and an ardent supporter of civil rights, Pusey later said he barely knew King, but was struck by the energy of his admirers.

Behind King in the picture, and to his left, standing on the steps to Appleton Chapel, is the Rev. Charles P. Price ’41, a World War II Navy veteran and summa cum laude mathematics graduate of the College. He was University Preacher and Plummer Professor of Christian Morals from 1963 to 1972. It was Price who escorted King across campus. Pusey, meanwhile, led the waiting congregation through hymns and readings. The church was full, and latecomers crowded into Sanders Theatre to hear the sermon.

“Everywhere, well-wishers mobbed King,” wrote student journalist Ellen Lake ’66. The summer before, she had taken part in the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, an attempt by volunteers — largely white college students from the North — to register voters.

At the Memorial Church, King cautioned against hatred and revenge, despite the violent cauldron of political fervor surrounding the civil rights movement. “The philosophy of an eye for an eye,” he said, “results in everyone being blind.”

But King pulled no punches, either, calling for federal voting registrars in some Southern ballot districts, and legislation to end de facto segregation in schools. (By the summer of 1965, Lake had co-founded The Southern Courier, a civil rights newspaper in Georgia and Alabama that closed in 1968.)

Another Harvard student reporter was in the audience to hear King deliver his sermon. Jacob Brackman ’65 would go on to a career as a journalist at Newsweek, The New Yorker, and Esquire, and as a Broadway lyricist and movie producer. His story three days after the visit recalled three standing ovations at the church, as well as the power and musicality of King’s preaching cadences, “his basso ‘m’s’ fading out, and ‘r’s’ rolling …”

King also talked about the “four plateaus” in the upward climb to American racial equality, from slavery to post-Civil War segregation, to legal steps outlawing segregation. The fourth plateau, a “New Jerusalem” of equality, was yet to come. King also repeated his 1962 message at HLS that legislation could not make someone love him, but could prevent his lynching. “That’s pretty important too,” he said. Laws, King said, could at least “restrain the heartless.”

After the sermon, Price hosted a luncheon for Pusey and King. It was here that Brackman — flexing the descriptive powers that would later serve him in the literary arts — provided an intimate look at the visiting King, who was “natty as a J. Press ad in his three-piece continental suit,” wearing cuffless pants and laceless black shoes.

“Style,” wrote Brackman. “That is what characterizes King best. Not the elemental, visceral appeal of a roughed-up revolutionary, but the smooth polish of a movie star, an haute politician, a foreign car salesman. He is a handsome, clear-eyed man with an air of good living, almost of opulence. Instinctively, he pauses in his speech and turns to the cameras.”

But behind the polish was the substance. In September 1964, a month before getting the Nobel Prize, King visited Boston to announce he was donating his papers to Boston University. During a streetside rally, he delivered a message that seems obvious today: that racial inequality had a home in the North as well as the South. “Injustice anywhere,” he said, “is injustice everywhere.”

Three months after his January 1965 visit to Harvard, King was in New England again, this time to address a joint session of the Massachusetts Legislature on April 22. Nearly word for word, he repeated the closing of his “I Have a Dream” speech from two years before.

The next day, King was at the head of the first civil rights march he ever led outside the South, a procession of thousands from Roxbury to Boston Common.

The march took King past 397 Massachusetts Ave., a three-story row house on the Roxbury-South End line, where he had lived as an obscure graduate student little more than a decade before. That was 1952-1953. The civil rights march in Boston was partly an homage to the region that had introduced him to tactical nonviolence. Three years later, in that same month, in Memphis, Tenn., an assassin killed King. He was just 39. The rest is history.