The lives of Harvard’s Rhodes

Scholars studying and socializing in Oxford reflect on experiences at world’s oldest English-speaking university

OXFORD, England — “Studying at a place that has been around since before the Black Death is humbling and awe-inspiring,” said Alexander Diaz ’14.

A Rhodes Scholar from 2014–15, Diaz was intrigued by the University of Oxford, where some buildings go back more than 300 years before Harvard was founded. Diaz was captivated by meandering through the grassy meadows of Magdalen College, where J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis once strolled. He even visited the bench where many claim Tolkien sat when saw the two tall buildings that inspired his book “The Two Towers.”

“Oxford is full of wonderful treasures like that,” he said.

A recent trip to the world’s oldest English-speaking University revealed similar enthusiasm among current Rhodes Scholars from Harvard. A new U.S. Rhodes Scholar class will be announced on Saturday (Nov. 18).

“It was really magical,” said Garrett Lam ’16 of one of his first nights at Oxford, when he and a friend found themselves on the grounds of Magdalen, one of 38 constituent colleges at Oxford, feeding chestnuts out of their hands to a herd of deer.

Seated on a bench in the well-manicured, walled-in garden of the Rhodes House, the headquarters of the scholarship program, Lam said that Oxford is fascinating for having so many unusual spaces, from Gothic colleges to ornate dining halls to fields where deer laze. “Living at Magdalen College last year, I would open my door every morning, and there were 50 deer grazing on the grassland. It was a wonderful way to begin a day.”

For Hassaan Shahawy ’16, the scenic wonders are also the perfect backdrop for engrossing discussions. Studying for a D.Phil. in Islamic studies, Shahawy remembered stimulating talks with students while strolling along the Thames on sunny days, while rowboats glided down the gently winding river. He believes that compelling conversations can come easier at Oxford than at Harvard, where the academic pace is more bustling.

Enjoying dinner in a teeming downtown Lebanese deli where animated conversation swirled, Shahawy said that while half-hour discussions seemed long in a Harvard dining hall, at Oxford 90-minute talks are common. “My conversations in Oxford have given me the opportunity to really get to understand one person, to understand where they come from, what they think, and why they think that way.”

Shahawy said this might be because in many colleges in the U.S. a student’s time is regulated by weekly assignments, frequent exams, and strict reading obligations. At Oxford, he said, the academics are looser: Term papers are not formally graded, and deadlines are rarely enforced. Additionally, final exams are held at the end of a program, which for some students could be at the conclusion of two years of study.

Consequently, Shahawy said, Oxford allows more time for soul-searching, late-night talks. He remembers one dinner conversation with fellow Rhodes scholars that posited: Would you rather live forever or die tomorrow? Shahawy said four people said that they would like to live forever, but the other half argued that they would rather die tomorrow because only mortality gives life meaning and value.

Asked how he answered, Shahawy laughed. “I don’t really remember,” he said, scratching his beard and taking another bite of eggplant. “I think I kind of came out in the middle, but I do know that I enjoyed the conservation — and it wasn’t the only time we had it.”

Grace Huckins ’16, focusing on neuroscience and women’s studies, recalled interesting conversations at Oxford, but added that she has also been moved by the important thinkers and shakers who taught or studied there in the past, like Erwin Schrödinger, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist and fellow at Magdalen College in the 1930s. “Having studied physics and admired Schrödinger’s work, I was overwhelmed by the idea that he might have sat and ate in my same college dining hall.”

A fan of Tolkien’s books since childhood, Huckins said she was also awed when she visited the room in the famed Eagle and Child pub, where Tolkien and Lewis met regularly with fellow writers to give each other feedback on their work starting in the 1930s.

“Having experienced something like that, it can’t help but show you what your own potential can be, if you’re lucky enough to study in such an amazing place,” said Huckins, sitting in the colossal shadow of Radcliffe Camera, the iconic 14th-century columned, circular building in the heart of the medieval city.

Sipping a glass of water in an outdoor café next to the 13th-century University Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Anthony Wilder Wohns ’16, a D.Phil. student in statistics, said one can’t help but be impressed with the history of Oxford and its famous educators. But he added that the city’s social life is also special.

“People work hard here but then leave the classroom or lab and go to the pub to have fun,” he said. Raising his voice over the café’s boisterous late-afternoon din, Wohns said Oxford’s ubiquitous pub culture gives students and researchers plenty of places to converse with friends or meet people who might have expertise outside their areas of study, giving their research a different perspective. He noted that two people can work all day next to each other in the same lab but never get a chance to discuss their work. “The pub is a great place to connect and learn in Oxford.”

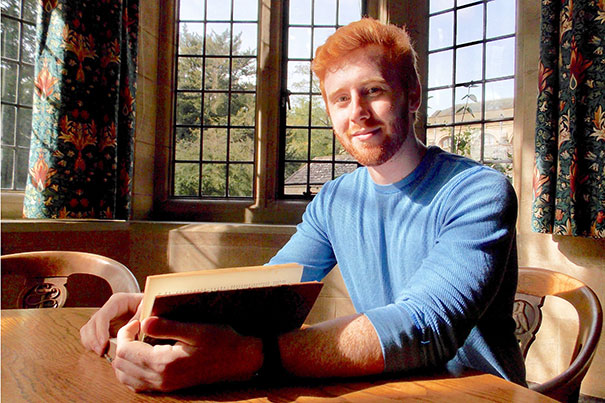

Not yet in Oxford two weeks, Spencer Dunleavy ’17 said he’s not sure what to expect next, but he has some early reservations about revealing to other students that he is a Rhodes Scholar. Taking a bite of cheese pizza in a restaurant near his apartment, Dunleavy said that he doesn’t even reveal he went to Harvard unless directly asked, because people might assume he’s wealthy and elite, similar to what they might assume if they knew he was a Rhodes.

There is another reason why Dunleavy, raised in a low-income household and the first in his family to graduate from college, doesn’t crow about his academic achievements. Dunleavy said he recently had a conversation with an Oxford student who told him about a female Rhodes Scholar whom he had just met. The student, who didn’t know that Dunleavy was also a Rhodes, raved about how remarkable she was and how much he wanted to learn about her amazing Rhodes journey. “And I’m thinking to myself,” said Dunleavy, “‘Yes, she’s amazing, but if you found out that I’m a Rhodes Scholar too, would I suddenly become more interesting to you?’” Dunleavy said that he — like most Rhodes Scholars — wants to be admired for who they are, not for winning the scholarship.

Reflecting on being both a Harvard graduate and a Rhodes Scholar, Dunleavy said graduating from Harvard was a much bigger deal for his family and friends. After he won the Rhodes, he went to a family christening and nobody mentioned that he’d won the world’s most prestigious academic award. “A couple of people said something like, ‘Oh, I heard that you got a something-something to go to England,’ and I just smiled and said, ‘Yeah, a something-something.’” Taking another bite of his pizza, he added, “And that’s the way I like it.”

Anthony Chiorazzi has an M.Phil. in social anthropology from Oxford University and a master’s degree in theological studies, with a focus on religion and the social science, from Harvard Divinity School. He has researched and written about diverse religious cultures such as the Hare Krishnas, Zoroastrians, Shakers, and the Old Order Amish.