Creating a new language in art and literature

Exhibition shows that ‘fin-de-siècle’ was also end of an era

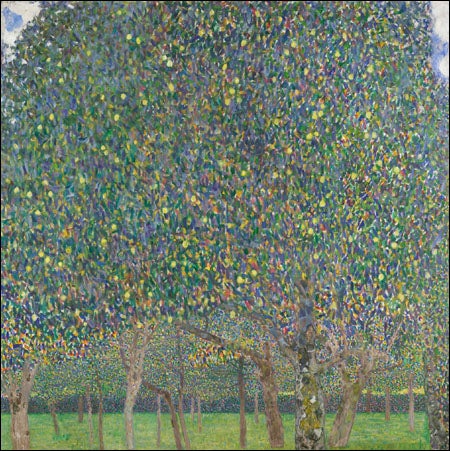

Thanks to a profusion of coffee-table books, reproductions, greeting cards, and other museum gift shop items, Gustav Klimt’s paintings now rank among the world’s best-known images. “The Kiss,” in which a man and woman in the midst of an erotic embrace seem almost to disappear into a mountain of richly decorated fabric, has become an iconic expression of romantic love almost as universal as a box of chocolates or a bouquet of long-stemmed roses.

To Peter Burgard, this use of Klimt as content provider for the Valentine’s Day industry is a curious and disconcerting development.

“Klimt has become very popular, but for the wrong reasons. ‘The Kiss’ is really a very disturbing image in which the man seems to be consuming the woman. As for the decorative element, it’s actually very subversive. It’s not there just to be aesthetically pleasing.”

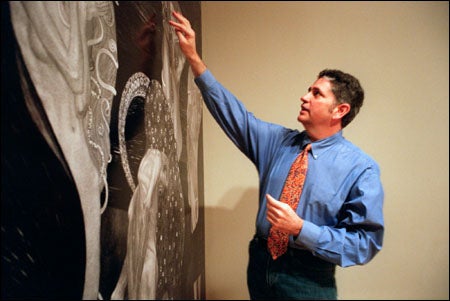

Burgard, a professor in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, is teaching a core curriculum course this spring called “Repression and Expression: Literature and Art in Fin-de-Siècle Germany and Austria.” An exhibition at the Busch-Reisinger Museum titled “‘As though my body were naught but ciphers’: Crises of Representation in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna” is designed to complement the course, indeed, said Burgard, to be an integral part of it. Hearing Burgard’s lectures, however, is by no means essential to an appreciation of the exhibition. A collaboration between Burgard and Laura Muir, the Museum’s Charles C. Cunningham Sr. Assistant Curator, the exhibition brings together words and images in a way that reveals the disturbing tensions lurking beneath the now-familiar surfaces of these turn-of-the-century artworks.

The exhibition highlights the interrelations between works by members of the Vienna Secession school like Klimt, Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, and Josef Hoffmann, and their textual counterparts – works by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Arthur Schnitzler.

“The art is literally being contextualized. This is art displayed under the sign of literature,” said Burgard.

A text by Hofmannsthal serves as key to the ideas expressed by both the writers and artists. “The Letter of Lord Chandos,” exhibited in its first published form in the German newspaper Der Tag (1902), is a first-person narrative in the form of a fictional 17th century letter from a “Lord Chandos” to his friend Francis Bacon. In it, Chandos explains that he has given up writing because for him the conventional forms of language have lost their ability to represent the world.

At the same time, he has become captivated by everyday, seemingly insignificant experiences, including physical sensations. “As though my body were naught but ciphers,” a phrase from the text, expresses this perplexing sense that reality demands a new language that does not yet exist. Hofmannsthal hints at the nature of this new language when he suggests that “we could enter into a new and hopeful relationship with the whole of existence if only we begin to think with the heart.”

According to Burgard, the “intense theorizing about linguistic referentiality, the ability of words to render the world” that characterized the intellectual life of this period had its exact counterpart in the rejection by artists of the conventions of pictorial realism.

Nowhere is this graphic revolution more evident than in the murals Klimt was commissioned to paint for the Great Hall of the University of Vienna between 1898 and 1907. The assigned subjects – “Philosophy,” “Medicine,” and “Jurisprudence” – no doubt would have inspired a more mainstream artist to devise a classically based composition replete with conventional symbolic figures embodying the dignity and antiquity of these disciplines.

Not so Klimt. His compositions were symbolic, but hardly conventional. One of them, “Jurisprudence,” is represented in the exhibition by a life-sized black-and-white reproduction.

This and the other two murals triggered a scandal when they were first exhibited. During World War II, all three paintings were moved to a castle north of Vienna for protection. In May 1945, retreating Nazi troops set fire to the castle to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, destroying the three paintings as well as a number of other Klimt works.

In Klimt’s mural, three female forms at the top of the painting, nearly hidden by mantles of sumptuous fabric, represent Truth, Justice, and Law. In the foreground, an elderly, decrepit, naked man seems to be surrendering himself to a giant, jewel-encrusted octopus, while a second trio of women, occupying three separate swirling, decorative spaces, look on with somnambulistic malevolence.

After 100 years, the painting still has the power to baffle and disturb, but for Burgard its significance lies in the fact that it unites the three elements that most characterize the art of this crucial period. As Burgard’s label states, “‘Jurisprudence’ illustrates the confluence of the feminine, the decorative, and abstraction in a subversion of the phallic order.”

The abstract and the decorative were the new graphic languages that Klimt and his colleagues turned to as they turned away from naturalistic representation. And, as in “Jurisprudence,” the abstract and decorative often appeared in association with the feminine. Here the sinuous octopus with its highly decorated surface seems to be a sort of apocalyptic extension of the feminine about to obliterate the now impotent representative of the patriarchy.

‘”As though my body were naught but ciphers”: Crisis of Representation in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna’ is at the Busch-Reisinger Museum through June 12.

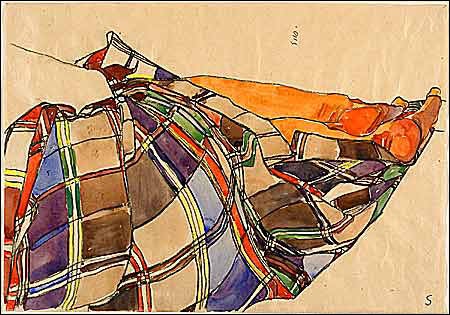

This subversive triumvirate – the feminine, the decorative, and the abstract – can be seen in many of the other works on display, from Alfred Roller’s poster for the fourteenth exhibition of the Vienna Secession in 1902 with its abstract female figure surrounded by bold, decorative elements, to Egon Schiele’s “Sleeping Figure with Blanket,” in which the colorful tartan draping the female figure appears as pure abstraction until the viewer discovers the bare feet emerging from beneath.

Most of the art on display comes from the Harvard University Art Museum’s own collections. Most of the literary works are first editions from Houghton Library.

“The overarching idea of the exhibition,” Burgard said, “is the intersection of literature and art. I wanted the students to experience it firsthand, with an immediacy they could never get in a lecture. I also wanted people to see what extraordinary resources we have here at Harvard and how they can be used in teaching. There’s no other university where you could teach a course on this crucial period in cultural history and simply walk across the street to see the works of art and the original texts from the University’s own collection.”