Reversing Saddam’s ecocide of Iraqi marshes

Series of conferences, exhibits, work on ‘re-gardening’ Eden

Until the early 1990s, the marshes of southern Iraq were a critical environmental lifeline, a source of water and nourishment in the desert, and home to Arab peoples who made their living from marsh fish, plants, and wildlife.

They were also a refuge out of reach of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, who, after the 1991 Gulf War, drained the marshes as part of his effort to put down a rebellion by Iraq’s Shiite Muslims.

Hussein dug a series of canals that diverted the water, drying up 90 percent of the marshes, which were once the largest wetland ecosystem of western Eurasia. That forced an exodus of an estimated 500,000 marsh dwellers and effectively ended a way of life that had persisted for millennia.

It also represented an environmental disaster, killing fish and native plants and depriving many migrating bird species of an important stopover on their journey from wintering grounds in Africa to breeding territory in Asia.

Beginning today (Oct. 28) at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, experts in

environmental engineering, ecotourism, and water management will join with policy-makers, scientists, and former marsh dwellers in a three-day conference that takes a broad-based look at the prospects for restoring the marshes.

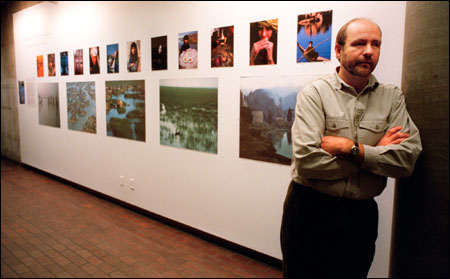

Though restoration work has been under way since shortly after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, conference organizer Robert France, adjunct professor of landscape ecology at the Graduate School of Design, said it’s important to help guide the effort by drawing on similar restoration experiences from around the world.

The conference is sponsored by the Center for Technology and the Environment at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), the University Center for the Environment, the Center for International Development at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, and by the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture.

Almost as soon as U.S. troops unseated Hussein, marsh dwellers began breaching his dikes and canals, restoring the water flow from the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers into what some believe is the site of the biblical Garden of Eden. By May 2004, 40 percent of the marshes had been reflooded and some had begun to recover on their own.

But France said restoring the marshes is far more complicated than merely restoring water flow. There are important environmental issues, such as how to deal with a saline crust left behind when the water dried and which has the potential to pollute marsh waters.

There are also questions of whose vision to follow in restoring the marshes. Though they are viewed by some as a natural environment, France said the marshes have been home to humans since the times of the Sumerians, 5,000 years ago, and are amid a landscape that is among the most manipulated on Earth.

Among questions to consider is whose vision guides the restoration work and whether the marshes are being restored as an environmental hot spot or as a functioning home to which marsh-dwelling Arabs can return and live.

“We have a myth of an unmanipulated environment,” France said. “We think of Eden as an unmanipulated place, but to ancient Mesopotamian Sumerians, the marshes weren’t their idea of Eden.”

France cautioned against romanticizing life in the marshes, which was hard, bug-infested, and lacking in proper sanitation facilities – a problem in a place where food and drinking water were drawn from the same source into which wastes were disposed. Some of the refugee marsh dwellers, France said, have adjusted to dryland farming and aren’t interested in returning to their former lifestyle.

But many are. In fact, more than 42,000 have already returned to the reflooded marshes, according to Eden Again, a nonprofit organization that is dedicated to restoring the Iraqi marshes.

The conference runs over three days, (Oct. 28-31) with a postconference panel. In between are a wide variety of speakers, including officials from Iraq’s Water Ministry and the United States Agency for International Development, which is a major backer of restoration projects. Participants will also hear from scientists and engineers who’ve had extensive experience with similar desert restoration projects in Israel, Mexico, and other locations. Other topics include wastewater handling, local involvement in sustainability projects, agriculture, technology, and history of the area.

France said the conference is benefiting from several related events occurring at Harvard, including two photo displays of Marsh Arab culture, at the Peabody Museum and at the Graduate School of Design’s Gund Hall. There was also a public lecture on preserving Iraq’s antiquities that took place Wednesday (Oct. 27) at the Sackler Museum.

France said he expects one or two books to result from the conference, and, after the conference’s closing, to present findings to Iraqi officials involved in restoration efforts, but who weren’t able to attend.