Susan Dackerman (photo 1), consultative curator of prints, examines the design for the Boston Gas Co. tank created by Corita Kent in 1971. At the Harvard Art Museums, “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” examines the artist’s work within the context of the pop art movement and the social and cultural currents of the time. Inspired by a Del Monte food slogan and the reforms in the Catholic Church introduced during Vatican II, Kent’s work “the juiciest tomato of all” (photo 2) evokes the everyday and the divine. Kent’s painted gas tank (photo 3) became a “pop art landmark for Boston,” said Dackerman.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; (1, 3) Boston Gas Tank model provided courtesy of National Grid

Putting an artist in her place

New exhibit explores Corita Kent’s work in the pop movement

In 1962, a commercial illustrator from New York rocked the art world with his first one-man show. Some viewed the Los Angeles exhibit as little more than a clever novelty; others mocked its use of commercial subject matter as fine art. But for many, including one artist from a nearby Catholic order, Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” was a revelation.

From the moment she visited the Ferus Gallery, where Warhol’s 32 paintings were on display, Sister Mary Corita (later Corita Kent) found it hard not to see the world through the lens of those captivating cans.

“Coming home,” said Kent, “you saw everything like Warhol.”

Kent’s own work, informed by social activism, would soon begin to reflect that vision. “She was exposed to this avant-garde art practice right at the very beginning,” said Susan Dackerman, the former Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints at the Harvard Art Museums and current consultative curator of prints. “And she is totally open to it.”

Dackerman is the curator of “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop Art,” an exhibit opening this week at the Harvard Art Museums that positions Kent and her work as central to an art movement famous for celebrating kitsch and consumer culture. For years Kent has been looked on as something of a footnote in pop discussions, overshadowed by male artists such as Warhol, Jim Dine, and Roy Lichtenstein. But the Harvard show places Kent in the middle of the conversation, calling attention to her influences, her contributions, and her unique perspective.

“What we wanted to do was actually look closely at her work, and look at it in a broader cultural, art-historical context,” said Dackerman, “and put it into the art-historical discourse.”

The exhibit features a selection of books and films about the artist, and alongside 60 Kent prints includes for comparison 60 works by her contemporaries, among them a print by Jasper Johns. In his 1962-63 work “Red, Yellow, Blue” Johns plays with the definition of color, spelling out the work’s title in black and white. His artistic choice “strips the words of their meaning,” said Dackerman. Similarly, Kent divested words of their original intent in her prints, “but what she does then is reinvest them with other meaning.”

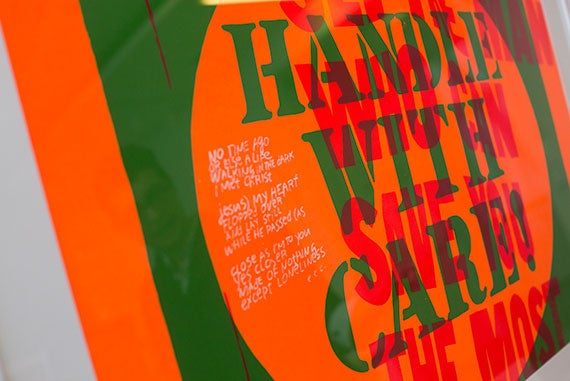

Kent’s “handle with care,” an eye-catching green and orange print, incorporates a popular Chevrolet slogan that referred to one of the company’s many car dealers. But for the Catholic nun, the words “see the man who can save you the most,” clearly carried a deeper significance.

In Kent’s hands, Dackerman said, the salesman offers you “a Chevy, and salvation.”

For Kent, any text was fair game. Lines from the Bible, poems, and even Beatles songs made their way into her prints. One of her richest sources of inspiration was the world of advertising, said Dackerman, who spent years researching the show and writing its catalog with Jennifer Roberts, the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities, and several Harvard grad students. “She also used the ads in Playboy. She was a nun, but she was out there in the world.”

That meant Kent was tuned in to the artistic currents as well as the social and religious movements of the time. The Harvard show explores how the reforms of Vatican II, the Catholic Church’s effort to catch up with the times, affected Kent’s output. (Among the many reforms, priests saying Mass could both face the congregation and speak in a language other than Latin.)

“Characteristics of pop art and the aspirations of Vatican II overlap; they merge simultaneously,” said Dackerman. “Pop art is also looking for a broader audience. Pop art also turns to vernacular subject matter.”

Kent saw in both movements an important artistic overlap. Her screen print “the juiciest tomato of all,” borrows from Warhol’s tomato soup cans, and from a letter by a professor who described the Virgin Mary in modern terms that included the repurposed Del Monte slogan “the juiciest tomato of all.” Her resulting work evokes the daily and the divine.

“She’s just a really smart artist,” said Dackerman.

Born Frances Elizabeth in 1918 in Fort Dodge, Iowa, Kent grew up in Los Angeles and joined the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary as a teen, where she took the name Sister Mary Corita. She graduated from Immaculate Heart College in 1941 and began teaching art at the school in 1947. From the beginning, her classroom and studio were hubs of creativity, where students and fellow nuns assisted her with her work. “It’s not really that different from Warhol’s factory,” said Dackerman, “except everyone’s dressed a little different.”

Kent’s reputation for innovation attracted some of the era’s brightest stars.

“Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, they were all there and they gave lectures and they talked to the students,” said Dackerman. Kent even made the cover of Newsweek in 1967 as an example of the modern nun. But history, said Dackerman, has failed to “put her at the center of anything.” The curator hopes the new show moves the artist “back into that art-historical conversation.”

That effort began in earnest several years ago when the museum acquired approximately 70 works by Kent. It was a move aimed at making Harvard a focal research site for scholars interested in the artist, said Dackerman, by adding Kent’s work to Kent material already at Harvard. Between 1990 and 1991 the artist’s estate donated her official papers to the Schlesinger Library, which is currently hosting an exhibit of material from its collection. “Corita Kent: Footnotes and Headlines” is on view at the Schlesinger through Sept. 18.

Perhaps Kent’s most enduring images are those at the extremes — her smallest and biggest. In 1985 she created her “Love” postage stamp, bright horizontal strokes of color that hover about a purple “love,” and resemble Robert Indiana’s love stamp from 1973. Her largest piece is represented in the Harvard show by a wall-sized photomural and a 7-inch high model. Many have glimpsed the real thing, but only at high speeds — the giant rainbow swash painted on the gas tank along Interstate 93 in Boston. (Kent left the order in the late 1960s and moved to Boston, where she lived and worked until her death in 1986.)

For Dackerman, the gas tank represents the culmination of Kent’s work in the pop movement, and calls to mind Ed Ruscha’s famous depiction of the Hollywood sign. By sprucing up the broken letters, relocating them to a ridge, and highlighting them against a brilliant orange-red sunset, Ruscha’s print infused the sign with new life and meaning. His revitalized image “becomes this iconic example of pop art,” said Dackerman, “and then, in the wake of that, the Hollywood sign itself becomes this iconic pop symbol and this city landmark.”

Kent, who spent much of her life living not far from the sign, couldn’t have missed this transformation.

“Corita grows up essentially in the shadow of this sign and she sees this transformation take place,” Dackerman said. “So that in 1970, when the Boston Gas Company says ‘Do you want to paint this tank?’ I think what she does is actually make a pop art landmark for Boston.”

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” opens Sept. 3 and runs through Jan. 3 at the Harvard Art Museums.