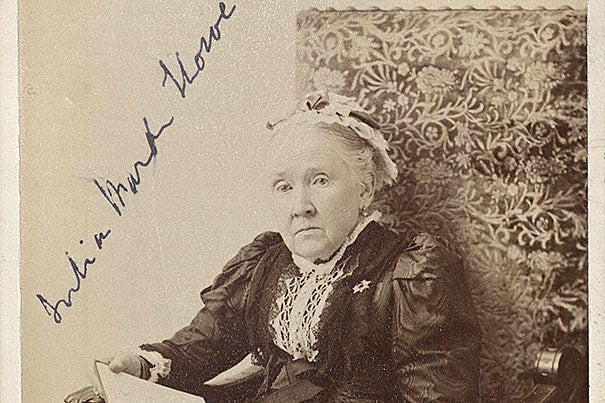

Abolitionist Julia Ward Howe, who wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” in 1861, posed for this Boston portrait around 1909 (photo 1). An 1836 almanac entry noted the Aug. 1 abolition riot that rescued two fugitive slaves from a Boston courtroom (photo 2). An 1863 Currier & Ives print celebrated Boston’s 54th Massachusetts, the first regiment of northern blacks, whose service illustrated the social tumult caused by the Civil War (photo 3).

Artifacts courtesy of Harvard Library

Boston, hotbed of anti-slavery

Student-organized exhibit at Houghton outlines region’s pivotal role in ending dehumanizing practice

Boston was the flashpoint of the American Revolution. It’s a city indelibly linked to many of the Founding Fathers, to the midnight ride of Paul Revere, and to George Washington’s fledgling Continental Army, whose first encampment was in Harvard Yard.

But Boston also played a central role in a much longer struggle for freedom: the one to end American slavery. Details of the big picture are on view through Aug. 23 in Harvard’s Houghton Library, host of a student exhibit called “Boston’s Crusade Against Slavery.”

The sounds of the struggle will be on display as well, at a 5:30 p.m. reading on Wednesday in Houghton’s Edison and Newman Room, of samples from the correspondence between poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and politician Charles Sumner.

The men, one from Cambridge and the other from Boston, represented two faces of the anti-slavery movement before the Civil War: one quiet and the other outspoken. Longfellow was an early abolitionist. His “Poems on Slavery” appeared in 1842, and his “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1860) is now read as a parable warning Americans about impending war. But in person he was quiet about his feelings and his frequent donations to the cause. (Longfellow’s 1856 account book — full of donations to abolitionist causes — is part of the exhibit.) His best friend Sumner was in no way quiet about his feelings, and in 1856 suffered a near-fatal beating in the U.S. Senate after delivering an anti-slavery speech.

Many other Boston-area figures are also featured in the exhibit. There are eight cases of letters, posters, pictures, and journals from Harvard collections. Look for Wendell Phillips, a wealthy graduate of Harvard Law School who gave up the arc of a conventional career in 1837 to devote himself to abolition. In the exhibit, a letter and photograph that were sent to Phillips dramatize how slavery by another name survived beyond the Civil War. The letter, from a black Union Army veteran, described a woman in Virginia who routinely burned the backs of the two teenage girls who were once her slaves. The photograph showed one of the girls, age 16, scarred and stooped, bare to the waist from the back.

Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave, author, and orator who spent seven years in Boston, is featured in the exhibit, too. An 1855 letter from him to Sumner showed that even abolitionists argued. The missive made two sharp points: that slaves, not white abolitionists, invented the anti-slavery movement, and that citizens of color were not treated equally. Douglass sensed, even among abolitionists, “a falling away from their first love, touching the recognition of the entire manhood and social equality of the colored people.”

But despite infighting and uneven ground in the movement, abolitionists nationally still looked to Boston as exceptional American territory. “Boston’s Crusade Against Slavery” points out that Massachusetts was among the first states to ban slavery (in 1783), lift strictures against interracial marriage (in 1843), and desegregate public schools (in 1855).

The exhibit also reaches back to the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), the first event to shake the foundations of slavery in the New World. That was led by freed slave Toussaint Louverture. He “beat the combined armies of Europe,” said Josiah Bonsey ’14, who assembled and annotated artifacts in one of the exhibit’s cases. “It inspired a whole generation.”

The exhibit outlines many themes, including the era of tenuous compromise that preceded the Civil War; the connection between early feminism and black emancipation; “music as memory” in the abolitionist movement (in the form of “spirituals, minstrelsy, and marching songs”); and the ways in which radical icon John Brown, who led a violent, short-lived revolt against slavery, shook the complacent liberalism of Concord, Mass., where he had twice visited in search of funding. “Brown shows us,” wrote author Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1859, “another school to send our boys to — that the best lesson oratory is to speak the truth.”

Nearly every case in the exhibit includes some stunning photographic find from the Harvard collections, including an undated ambrotype of a Haitian Revolution veteran, a straw boater in his lap; a carte de visite showing firebrand egalitarian William Lloyd Garrison in uncharacteristic repose, at ease with his daughter, Fanny; and a haunting late-life photo of Cambridge resident Julia Ward Howe, who penned the words to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The exhibit is the work of Bonsey and other students in a two-part 2012-13 seminar on emancipation taught by English Professor John Stauffer. (His latest book, released in June, is “The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On.”) Exhibit creators include Balraj Gill, a Ph.D. student in the history of American civilization program at Harvard, which Stauffer directs; National Park ranger Ryan McNabb, one of the readers; Suzanna Bobadilla ’13; Caroline Vernick ’14; Samuel Greenberg ’14; Alexander Heffner ’13; and Mary Gabrielle Prezioso ’13.

Han Yan ’13 created an online version of the exhibit with help from Enrique Diaz, a designer/multimedia specialist at Harvard Library.