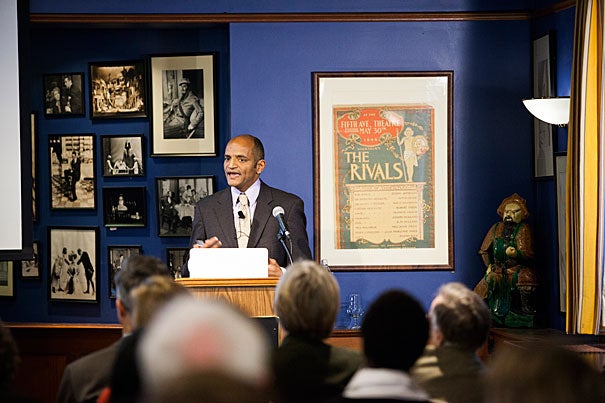

Art historian Steve Nelson traveled back to Harvard this week to present three talks on “Mapping Blackness in African and Afro-Atlantic Art.” His presentations open the Richard Cohen Lecture Series on African and African American Art at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mapping blackness in creativity

Art historian’s talks inaugurate Richard Cohen Lecture Series

As a child in suburban Boston, art historian Steven Nelson spent hours with his family’s 1969 edition of “The World Book Atlas,” an outsized volume crammed with hundreds of color maps. “We never traveled,” he said, so the book was a stand-in for doing so. “It was the way I learned the world.”

Nelson is a traveler now, having spent time in Africa and Europe. He has degrees from Yale and Harvard and is an associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, his home base for his prolific book writing and arts criticism. He is a contributing editor at the journal African Arts.

Nelson traveled back to Harvard this week to present three talks on “Mapping Blackness in African and Afro-Atlantic Art.” His presentations open the Richard Cohen Lecture Series on African and African American Art at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.

Nelson’s first lecture, Tuesday at Harvard’s Faculty Club for an audience of 80, discussed installation artist and sculptor Houston Conwill. Now in his 60s, the artist — who grew up Roman Catholic in Kentucky — has spent decades creating ways to represent the many-layered and labyrinthine ways that the African diaspora has rippled through American culture.

In the 1970s, Conwill reached for explicitly traditional African influences. He was famous for performance art “grounded in diasporic symbols,” said Nelson, like Dogon cosmology and juju boxes. Nelson showed a picture of Conwill in one performance piece, slathered with mud and slumped on a stool in an apparent trance.

Conwill was inspired by the Afro-centric black nationalist movement of the era, by his experiences at Howard University and in Los Angeles, and by landmark celebrations of African art, including “African Art in Motion” (1974) by Yale’s Robert Farris Thompson.

But Nelson’s argument was a rescue mission of sorts. He said that Conwill is not a modern-day shaman in an artist’s guise, but a careful researcher of the hybrid mysteries of African influences on American culture, from Middle Passage slave ships to plantation life, and to post-slavery, African-influenced art forms.

Nelson’s focus was on what could be called Conwill’s own Middle Passage: the mid-career years in the 1980s and 1990s when he began to map out the African-American experience in installation pieces, in art maps that defied “the presumed imperial gaze” of conventional maps, said Nelson.

Nelson chose two installation pieces to illustrate the evolving Conwill: “The New Cakewalk” of 1988 and “The Cakewalk Humanifesto: A Cultural Libation” (1989). The pieces share the subtext of the cakewalk, a dance performance that began as a way for slaves to parody the movements of their white masters, later evolved into a black art form, and eventually was used by blackface actors to parody American blacks themselves, in “a spoof of black behavior,” said Nelson. (He played a 1903 film clip of a cakewalk by black performers, who were clearly still making fun of white gentry.)

Conwill’s “Cakewalk” installations have a common blueprint: a blend of old Western culture (spirals inspired by the 13th-century floor labyrinth in the cathedral at Chartres), pictograms that echo traditional Africa, and dance diagrams that double as maps. Central to the imagery is “the labyrinth of the world,” said Nelson, with its images of loss and pain — but also of salvation, which is achieved by struggling to complete the spiraling course.

There is a kind of map in the installations, too. Like the four points on the compass, there are the fraught locales Memphis, Atlanta, Louisville, and New Orleans. In the middle is tiny Tuscumbia, Ala., the birthplace of Helen Keller, whose blindness and deafness, said Nelson, protected her from the color-line prejudices of her day.

The installations are not easy to navigate, said Nelson. As when trying to figure out the many-layered black American experience, he said, “You’re stopped at every turn.”

Cohen, a Manhattan real estate investor and manager, asked the first question just as the applause for Nelson died down. It was: “Could you repeat the lecture?” (His plane from New York had been delayed and he arrived late.) Near him in the front row, and laughing along with the joke, was Harvard President Drew Faust.

A few moments later, institute director Henry Louis Gates Jr. presented Cohen with the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal, the institute’s highest honor. Past recipients include Cornel West, Werner Sollors, the Rev. Peter J. Gomes, and Nobel literature laureates Wole Soyinka and Toni Morrison.

Cohen, a native of Brookline and a trustee at Boston University, has been invited to be chairman of the acquisitions committee for the institute’s new Ethelbert Cooper Gallery for African and African American Art, slated to open next spring. It will be the largest gallery of its kind in the country.