Citizen spies, spied-on citizens

Secret-police photos evoke the Iron Curtain era

The photos are unsettling, depicting years of humdrum, everyday life framed through the lenses of unendingly suspicious watchdogs.

“Prague Through the Lens of the Secret Police,” at Harvard through Dec. 21, is an exhibit of spooky images from the 1970s and 1980s. They depict the “normalization” period in Czechoslovakia, an intensely repressive interval between the Soviet-led crackdown in 1968 and the collapse of Communist rule in 1989.

The exhibit, at the Center for Government and International Studies, consists mostly of banner-size photos and text cards translated from Czech.

There are also six minutes of looped video. In one scene, filmed with a hidden camera, a man simply eats an apple. “From now on, when I eat an apple, I’m going to be watchful,” said Mark Kramer, a fellow and director of the Harvard Project on Cold War Studies, part of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The Czech secret police went to great lengths to keep track of people “who were perfectly innocuous,” he said. “These weren’t terrorists. They weren’t dangers to the state.”

The images, grainy and haunting, capture the dreary period known as “dumpling socialism,” a term of ironic nostalgia for Czech Communists. “The Prague we see,” reads the exhibit catalog, “is full of scaffolding, peeling facades, and socialist-era cars with two-stroke engines.”

The exhibit is from the Institute of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague, where a related Security Services Archive opened last year. The show’s first U.S. stop was the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Its second is Harvard.

Kramer has worked extensively in the Czech police archive. Stored end to end in file cabinets, he estimates, are more than 30 miles of documents. Czech authorities say it will take a decade to digitize all of that paper, microfiche, film, and photography.

Similar archives are open to the public in most former nations of the Soviet-controlled Eastern Bloc. But the Czech archive, established by law, is the freest and most accessible, said Jiri Ellinger, first secretary and head of the political section at the Embassy of the Czech Republic in Washington, D.C. At Harvard, he spoke at an opening reception Nov. 15 to a crowd of about 150.

‘Prague Through the Lens of the Secret Police’ Photos courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, Prague

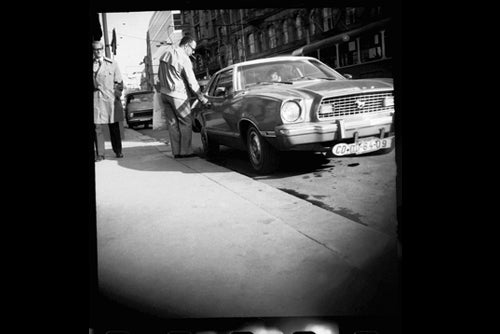

Prague 1984

A one-of-a-kind exhibition of photographs and films taken by the surveillance unit of the Czechoslovak secret police in the 1970s and 1980s, “Prague Through the Lens of the Secret Police,” is on display at Harvard’s Center for Government and International Studies through Dec. 21. This is the second stop in the exhibition’s U.S. tour.

Prague 1978

One of the exhibition’s aims is to show those who never experienced life in a Communist dictatorship what the secret police actually did at the behest of Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime.

Prague 1985

The camera was hidden under a coat, in a suitcase, or in a handbag. The Communist secret police would release the shutter at moments when they felt the subject was in front of the hidden lens.

Prague 1977

These never-before-seen photographs and films of “subjects of interest” were taken secretly during the “normalization” era of hard-line socialist entrenchment after the 1968 Soviet-led occupation of Czechoslovakia, according to the exhibition notes.

Prague 1977

“Prague Through the Lens of the Secret Police” introduces the visual products of the activities of a special unit of the Communist secret police (Státní bezpečnost, or StB) – the Surveillance Directorate of the Interior Ministry – which carried out surveillance of Czechs, Slovaks, and foreigners whom the Communist regime deemed hostile or suspicious in any way.

Prague 1978

The secret shadowing of designated people was carried out by about 200 policemen.

Prague 1984

Exhibition material quoting official documents: “Photographic documentation must give us a clear and precise picture of actualities which have a causal relationship to the subject …”

Prague 1985

The officers’ most commonly used exposure time was 1/125 of a second and often even 1/60 of a second.

Prague 1985

Camouflaging a Nikon camera was difficult. Servicemen installed the Nikon next to the radiator of a car and devised a vent for picture taking on the front grille. The driver controlled the camera, notes the book “Prague Through the Lens of the Secret Police.”

This is not an art exhibit, though the photos have “a peculiar charm,” said Ellinger. “Rather than enjoy it, I would ask you to think about it.”

The people in the pictures could not speak, read, or gather freely, he said. And the people taking the pictures thought of citizen surveillance as normal.

Still, the black-and-white photos, tilted and blurry, carry the unmistakable, if accidental, imprint of art. “An important work of art,” admits the catalog, “can also sometimes be created by people of whom it would not have been expected.”

The exhibit begs the questions: Who were these unintentional artists, whose photos can move onlookers years later? Who were these secret-police officials, whose naïve pictures — taken without aid of the human eye from satchels and pockets — evoke so vividly the drab Prague of the Communist era?

In 1948, when Czechoslovakia became a Communist state, there were 14 men in a special police unit who were spying on citizens. They had only one camera. By 1989, just before the Velvet Revolution transformed the Czech Socialist Republic into a democracy, 795 men and women were in the Surveillance Directorate of the State Security Service.

These domestic spies embraced a James Bond modernity. They used many cameras — concealed in tobacco pouches, purses, briefcases, transistor radios, lighters, and on engine blocks (for mobile surveillance). They mounted Sony television cameras in parked cars and in a baby carriage wheeled around by operatives posing as married couples. They ran up tabs for meals and beer. All was carefully archived, including deadpan written reports that read like postmodern fiction.

One began: “ALI was caught at the train station hall while perusing the arrival board. ALI was bareheaded, dressed in a white-striped outfit and white shoes. She was carrying a white plastic bag and a brown purse. Afterwards …”

Haviland Smith, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s station chief in Prague from 1958 to 1960, attended the opening. He called surveillance “an expression of the regime’s desire to stay in power — nothing more, nothing less.”

Surveillance was often layered, professional, and constant.

It could be comical too. Shortly after arriving at a Prague hotel, Smith’s wife complained how there was only one towel in their room. “Within two minutes,” he said, “there was a knock on the door, and the maid stood there with an armful of towels.”

By 1989, police spies had amassed more than 7,000 files on civilians. They gave their operations code names with novelistic resonance, including Rome, Tennis Player, Bula, and Condor. They nicknamed their surveillance subjects with similar verve: Alice 83, Smoke, Typist, and Aloe, for instance.

Producer 1, tailed from 1982 to 1989, was filmmaker Milos Forman. Doctor A — bespectacled, bearded, and on crutches in the exhibit photos — was Zdenek Pinc, a Prague professor of ancient philosophy.

“He was dangerous to the regime,” as were his beloved philosophers from 2,000 years ago, said Ellinger, because “he wanted to study and think freely.”

The Czech archive is important for more than Cold War scholarship, and “has immense value on the personal level,” said Ellinger, who was 15 at the time of the Velvet Revolution in 1989. “To know exactly what happened is the first step toward healing.”