Seamus Heaney reads at Sanders Theatre in 2008.

Harvard file photo

Seamus Heaney’s long migration

New collection traces life of courage, caution from Northern Ireland to Harvard

Seamus Heaney was widely celebrated for the lyrical beauty of his poetry, profound and reflective intelligence, and yeomanly commitment to his “digging” work.

The final fruit of his labors, “The Poems of Seamus Heaney,” was published in November, 12 years after his death. It runs nearly to 1,300 pages and can perhaps best be read alongside his selected letters, from 2024, with another 900.

Heaney’s death in 2013 was marked by widespread grief and gratitude, but there was a special pang at Harvard, where he lived, worked, and taught for almost 30 years. His Adams House pied-à-terre is still preserved, roughly as it was.

Heaney didn’t need Harvard to become what he became: the winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize for Literature, a bestseller, by his death probably the most famous poet writing in English.

Rather, the University and Heaney seemed to strike a happy friendship, meeting at the right moment: Just as his native Northern Ireland was descending into a maddening cycle of violence and retribution in the late 1970s, Heaney found in Cambridge space to spread out and to see his world anew.

Given his production of poems, essays, plays and epistolary friendship, it would seem wrong to call Heaney tight-lipped.

And yet there’s something there. “He was an incredibly careful writer and speaker … the most measured person I’ve ever met,” said Marilynn Richtarik, who took Heaney’s class in British and Irish poetry at Harvard in 1988, and is now a professor at Georgia State University.

Two-time former U.S. poet laureate Tracy K. Smith agreed. After idolizing and imitating his work in her early poetry, she learned from Heaney as a student at the College during the 1990s, when he held the Boylston Professorship for Rhetoric and Oratory.

Smith, who now holds that chair herself, remembers his “terse and deft” feedback, “highlighting a minor change capable of recasting or recalibrating an entire poem, inviting in another layer of association … awakening layers of weight and depth.”

Heaney took language seriously. In his 1987 poem “Alphabets,” he endowed early literacy with a sense of magic:

First it is “copying out,” and then “English,”

Marked correct with a little leaning hoe.

Smells of inkwells rise in the classroom hush.

A globe in the window tilts like a coloured O.

But there were other motives driving his circumspection — like the sense of the need to protect a public profile that came with childhood in a divided Northern Ireland.

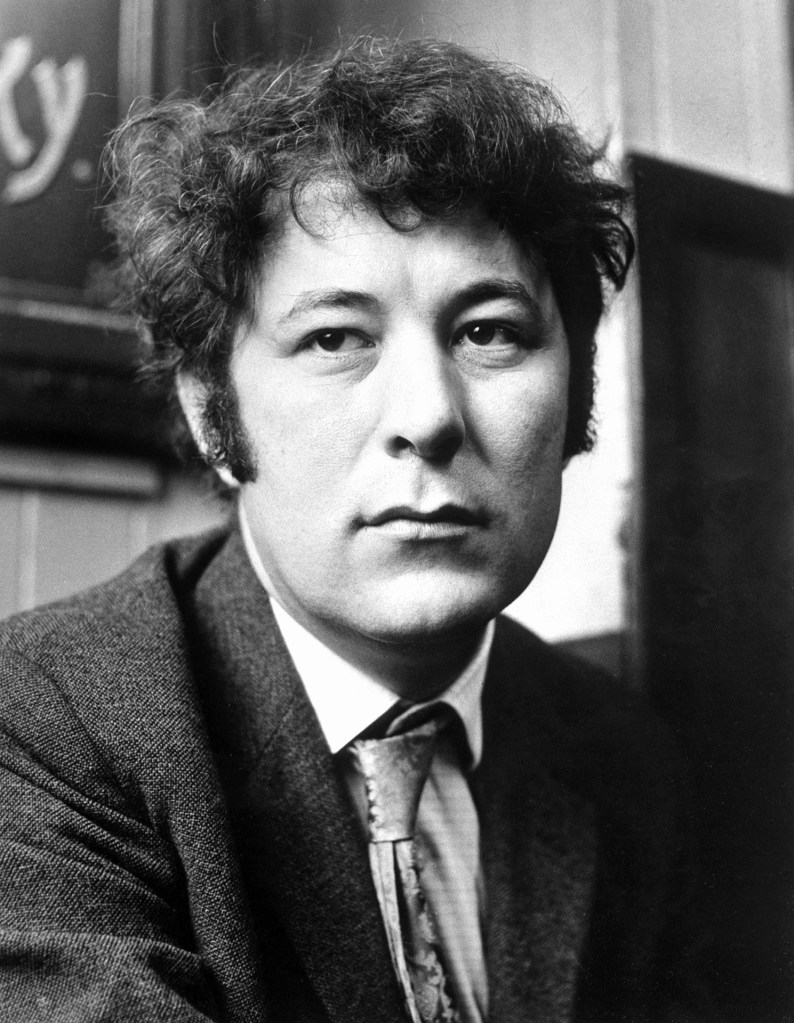

Heaney in 1970.

AP file photo

After all, it was Heaney who furnished journalist Patrick Radden Keefe with a title for his book on a 1972 killing in Belfast, when the poet wrote of “the famous Northern reticence”: … To be saved you only must save face / And whatever you say, say nothing.”

Heaney’s early poems contain what his friend and colleague the poet Henri Cole called “a substratum of violence,” mediated through history, nature writing, and allusion.

But the violence was present for him from its beginning. Heaney, not yet 30, was living in Belfast with his wife, Marie, and two young sons, Michael and Christopher, when the first bombs exploded in 1969.

Eventually the family did decamp in 1972 to the Republic — Dublin and Wicklow — far from the battle lines, where their youngest child, Catherine, was born. And that distance gave Heaney room to start saying something, as in the opening pages of 1975’s pivotal collection, “North”:

… I live here, I live here too, I sing

Expertly civil-tongued with civil neighbours

On the high wires of first wireless reports,

Sucking the fake taste, the stony flavours

Of those sanctioned, old, elaborate retorts:

“Oh, it’s disgraceful, surely, I agree.”

“Where’s it going to end?’’ It’s getting worse.”

“They’re murderers.” “Internment, understandably …”

The “voice of sanity” is getting hoarse.

“North’s” closing poem, “Exposure,” wishes for transformative power — “If I could come on meteorite!” — before lapsing into a sad reflection on the impotence of a “thoughtful … inner émigré” before the spreading chaos:

Instead I walk through damp leaves,

Husks, the spent flukes of autumn,

Imagining a hero

On some muddy compound,

His gift like a slingstone

Whirled for the desperate.

How did I end up like this?

Surrounded by family, Heaney accepts the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995.

Eric Roxfelt/AP

In the fall of 1978, the émigré re-immigrated to Cambridge for his first stint as a visiting lecturer in writing at Harvard.

The timing couldn’t have been better.

The poems in “North,” Heaney told Cole in his 1997 interview in the Paris Review, had been written in a frenzy of dislocation and angst: short and lacerating lines, a claustrophobic feeling. “I had my head down like a terrier at the burrow, going at it hot and heavy, kicking up the mold,” he said. “That wasn’t going to happen twice.”

The Heaneys sought an income, calm, community, and time to work.

His contract would have him teaching for four months and free to write and return to Ireland in the remaining eight. And here he built a second community, notably with critic and teacher Helen Vendler (née Hennessy) and poet Frank Bidart, and with generations of students.

But his mind and heart were at least partly elsewhere.

What began as a whole-family relocation to an apartment on Crescent Street in Cambridge soon became a solo affair. In the Paris Review, Heaney likened his Adams House apartment to “nesting on a ledge, being migrant” — a trans-Atlantic life designed not to separate him from Marie, the children, or from Ireland for much more than six weeks at a time.

And then the Troubles were with Heaney always — as the violence had begun to touch his world directly.

At Harvard, his lines relaxed, and his candor grew. “Field Work,” proofed and finalized from Cambridge, contains real, firsthand elegies: for a beloved pubmate, “blown to bits / Out drinking in a curfew,” and for a cousin killed at a bogus roadblock set up by Protestant loyalists. In “The Strand at Lough Beg,” Heaney addresses him, using dew to wash “the blood and roadside muck in your hair and eyes.”

Heaney’s portrait is unveiled in Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room in 2000.

Harvard file photo

A photo of the poet is displayed in his former Adams House suite, preserved by Harvard as a space for writing and reflection.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

At Commencement in 2012, Heaney reprises “Villanelle for an Anniversary,” which he composed for the University’s 350th anniversary in 1986.

Harvard file photo

But it was sometimes an ugly and uncertain enterprise. After “Field Work,” Heaney wrote the long poem “Station Island,” in which the same murdered cousin greets him with reproach:

The Protestant who shot me through the head

I accuse directly, but indirectly, you

who now atone perhaps upon this bed

for the way you whitewashed ugliness …

And saccharined my death with morning dew.

That self-criticism, an almost church-going reserve, is what former doctoral student DeSales Harrison still finds distinctive about his former teacher.

“He felt that his experiences — even the ones that were most personal — were not entirely his own to exploit for aesthetic purposes,” said Harrison, now a professor of English at Oberlin College. So confessional poetry was, “in some way, sort of trespassing, what he once called ‘rampaging’ through the suffering of others.”

Heaney refused, even in person, point-blank, to “propagandize” for the IRA, though they shared a religion and culture, to the consternation of some of his countrymen.

He abhorred the Catholic paramilitaries as much as the Protestant ones. “In the end, they’re all anti-artistic constituencies,” he once wrote to the playwright Brian Friel, his close friend.

But “The Cure at Troy,” his 1990 drama repurposing Sophocles, amounted to the nearest thing to encouragement for a nascent peace process, Richtarik argued in Harvard Magazine. Written at least partly in Cambridge, and set amid the ravages of the Trojan War, the play’s chorus imagines a miraculous reversal:

History says, “Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.”

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

Soon after that play was first performed, Heaney and Ireland experienced just such a moment, as a 1994 ceasefire led to the Good Friday Agreement that effectively ended sectarian violence in Ulster four years later.

The verse became a political cliché: first wielded by Bill Clinton during a peace-process visit to Derry, then again as the soundtrack to a 2020 campaign ad for Joe Biden.

That sort of deployment can make Heaney feel a bit out of date, as if his hoped-for tidal wave came then crashed, the world re-polarized and old conflicts reignited just as he left us.

“Seamus believed poetry was a kind of writing in the sand — that could change things.”

Henri Cole

But Richtarik argued that Heaney was no naïf. If today peace in Northern Ireland feels predestined, even in the early 1990s, “It really looked as if it might tip over into a kind of Bosnia, Serbia-type situation. It didn’t happen, but it could have.”

Heaney had watched a cycle of war and peace come and go, she said, seemingly for nothing. And his poetic response to the Sept. 11 attacks reminded readers: “Anything can happen, the tallest towers / Be overturned.”

Cole still remembers being “full of awe” during his five years in Cambridge, alongside Heaney, Vendler, Bidart, Robert Pinsky, and many others. “It felt like the epicenter of poetry.”

Asked about that lifelong preoccupation — about the “redress of poetry,” its responsibility — Cole noted that Heaney always returned to the moment in the Gospel of John, in which Christ is presented with a woman about to be stoned to death for adultery.

Before and after he warns the Pharisees — “let he who is without sin …” — the Gospel insists, he “wrote on the ground.”

“Seamus believed poetry was a kind of writing in the sand — that could change things,” Cole said. “I think he would still say that one of the functions of poetry is to interrupt, to shift the conversation, to change the focus, to re-examine ourselves and our hearts.”