Mapping our deep-rooted relationship with medicinal plants

Images via Nicolás Baresch Uribe, WA USA, Nawal Shrestha; illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Regions with longer histories of human settlement tend to have greater variety, study finds

Long before modern pharmaceuticals, our ancestors turned to plants to find cures for ailments from infections to parasites to fevers. A new study by Harvard researchers reveals the deep roots of that relationship: Several hot spots of medicinal plant diversity correspond to regions with long histories of human occupation and ancient medicinal traditions.

“It seems to be a relatively straightforward effect of the time in which humans had to experiment on these new landscapes that they settled in,” said co-author Charles C. Davis, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and curator of vascular plants in the Harvard University Herbaria. “Human ingenuity takes time — and I think that that’s what we’re seeing. As humans were exploring the flora, they were identifying which plants might actually be useful for medicinal purposes.”

In the study, published in Current Biology, Davis and his colleagues tallied the number of plants used in regions around the world as medicines, lotions, fragrances, intoxicants, and other non-nutritional uses. Those numbers were compared against a baseline of overall floral diversity in 369 regions around the globe.

The analysis included more than 32,000 medicinal plants among more than 357,000 vascular plant species, suggesting that about 9 percent had some kind of documented therapeutic use. The study included only vascular plants — which comprise the great majority of land plants — and did not include mosses, hornworts, and liverworts.

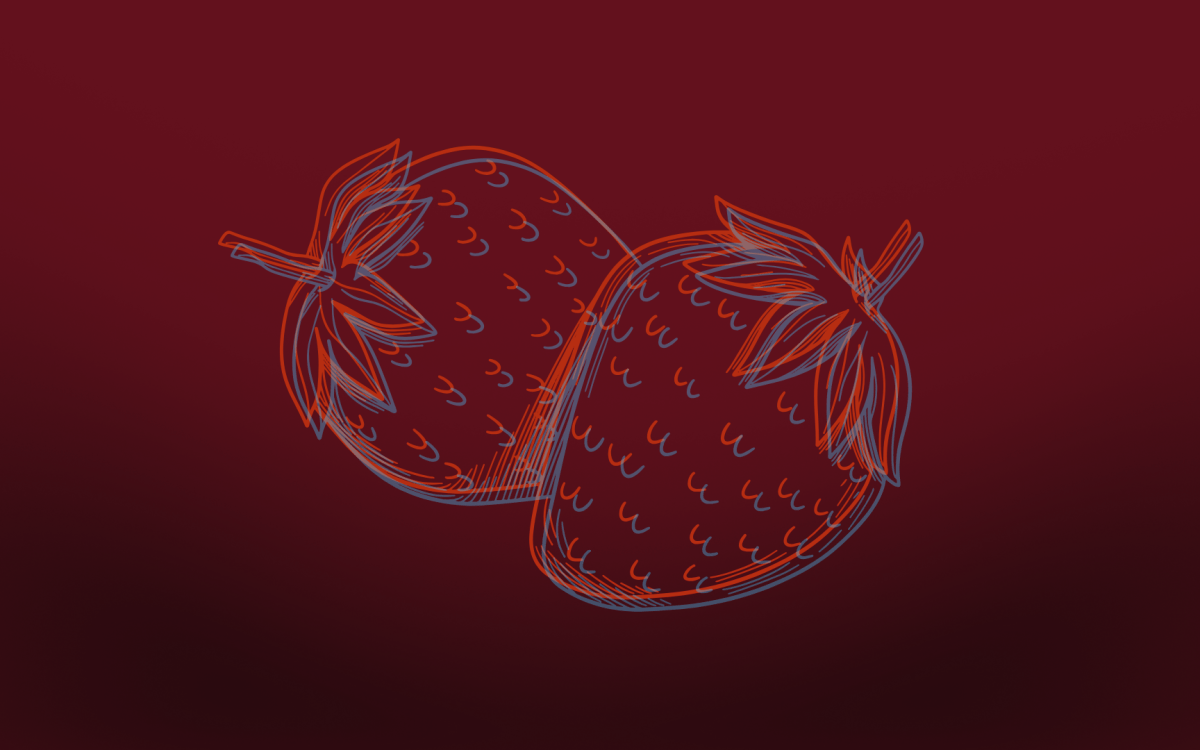

In general, diversity is lowest at high latitudes and increases toward the equator — and that pattern held true for medicinal plants. Not surprisingly, tropical regions with higher plant diversity had more types with documented medicinal uses.

Diversity of medicinal plants

Yet a few regions showed intriguing departures from this trend. The researchers discovered hot spots where the numbers of medicinal plants were relatively high compared to the baseline floristic diversity — particularly India, Nepal, Myanmar, and China. Not coincidentally, these regions also have ancient medicinal plant practices, such as Ayurveda of India and Nepal and traditional Chinese medicine.

“It seems that centuries to millennia of cultural knowledge and human interaction with plants have helped build and maintain this rich diversity,” said lead author Nawal Shrestha, research associate in organismic and evolutionary biology and currently assistant professor at Kathmandu University in Nepal.

Conversely, a few “cold spots” had lower-than-expected numbers of medicinal plants including the Andes, the Cape Provinces at the southern tip of Africa, Madagascar, Western Australia, and New Guinea. Surprisingly, some of these are megadiverse regions with abundant varieties of plants. But the authors acknowledged that the relative paucity of medicinal plants in these areas may reflect incomplete ethnobotanical documentation or heritages wiped out by colonialism.

“Many of these areas have rich local knowledge that has not yet been systematically recorded or incorporated into global databases,” said Shrestha. “It really highlights the need to work with local communities and revive traditional knowledge to better capture these resources.”

Fever bark (Cinchona lancifolia), the original source of the antimalarial medicine quinine.

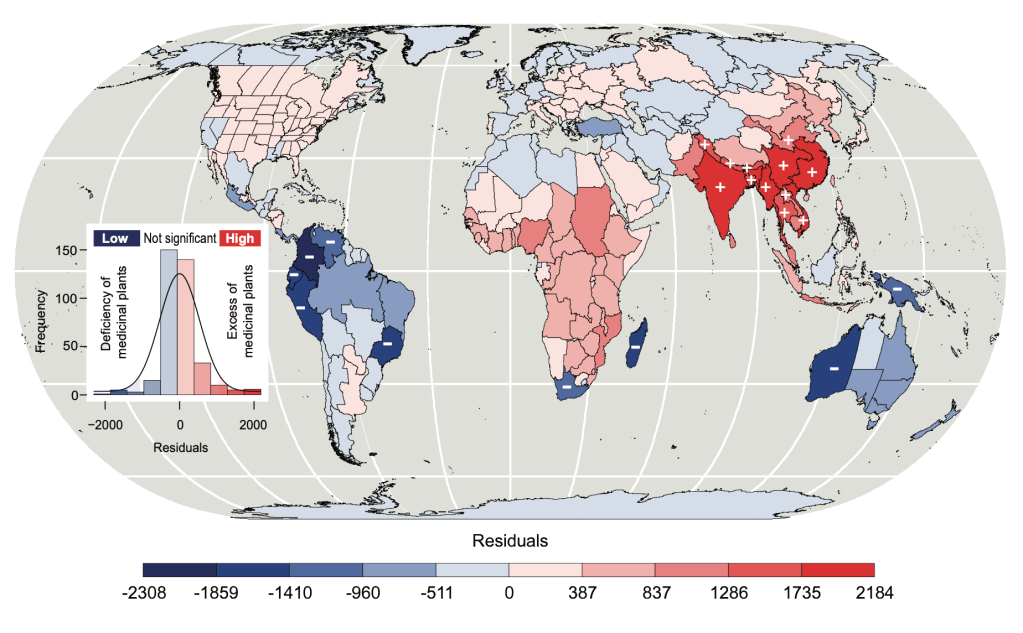

Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) contains compounds used in heart medications.

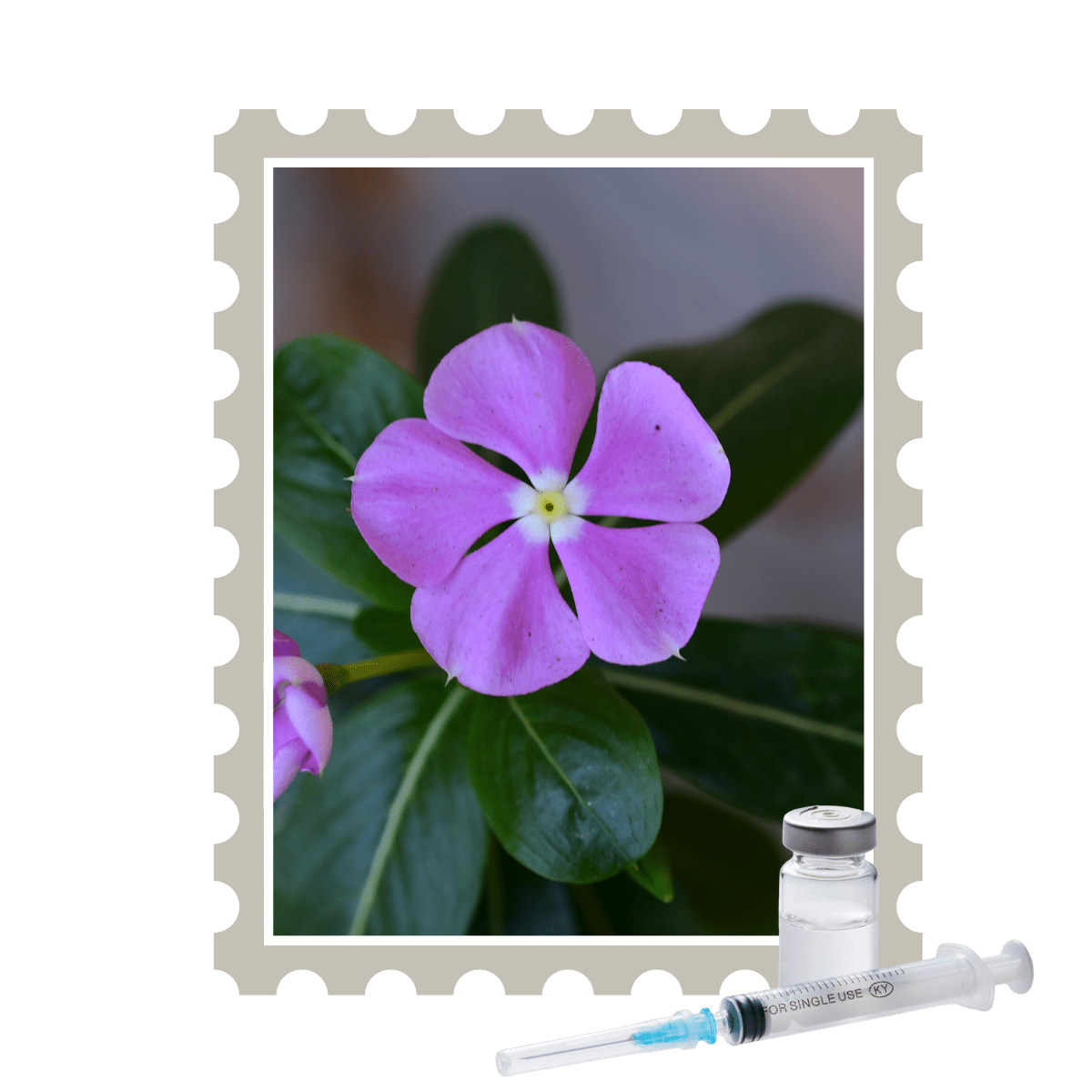

Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) was the source of the chemotherapy drugs vincristine and vinblastine.

Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) provided the anticancer drug paclitaxel

otherwise known as Taxol.

Overall, plant biodiversity turned out to be the strongest predictor of the regional diversity of medicinal plants. Strikingly, the second leading predictor was the time of settlement by modern humans — a dynamic not explored in previous studies. Regions with longer histories of human occupation tended to have more plants harvested by humans for medicinal purposes. For example, much of sub-Saharan Africa (the continent with the longest record of human presence) had more plants used for medicinal purposes, while similar latitudes of South America (settled between 25,000 and 15,000 years ago) had relatively fewer.

Plants lie at the root of our healing traditions. At least 25 percent of modern prescription drugs contain ingredients derived from plants. Fever bark (Cinchona lancifolia) was the original source of the antimalarial medicine quinine; foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) contains compounds used in heart medications; Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) was the source of the chemotherapy drugs vincristine and vinblastine; while the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) provided the anticancer drug paclitaxel, otherwise known as Taxol.

Charles Davis.

Harvard file photo

Nawal Shrestha.

Photo courtesy of Nawal Shrestha

Numerous studies have documented our ape cousins using plants for medicinal purposes such as wound healing or lotions. Traces of medicinal plants such as yarrow and chamomile have been recovered from dental plaque of hominin fossils.

The earliest known written documentation of medicinal plants comes from a 5,000-year-old clay tablet from ancient Sumer, which recorded drug recipes from more than 250 plant ingredients. References to medicinal plants also appear in ancient texts such as the Bible, the Talmud, the “Iliad,” and the “Odyssey.” Hippocrates — the so-called “founding father” of medicine — recommended some 300 plant remedies such as wormwood for fever, garlic for intestinal parasites, and opium as a narcotic.

But today this ancient heritage is threatened by global losses of biodiversity. Davis said the new study underscored the urgency of conservation and noted that somewhere amid the verdant biodiversity scientists may find “the next great cure.”

“Our findings reveal areas where not just biodiversity, but priceless traditional and local medical knowledge are at risk,” he said. “They must be prioritized for conservation and revitalization — and for future public health benefits to humanity.” The study was conducted with researchers from the Missouri Botanical Garden, New York Botanical Garden, VinUniversity in Vietnam, and LVMH Recherche.